Chapter 7 Indigenous mental health

Learning outcomes

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health

Partnerships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and mainstream health services need to be coordinated in ways that provide better health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (NATSIHC/NMHWG 2004). Building partnerships between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nurses and non-Indigenous mental health nurses are integral in this process. This requires a whole-of-life approach optimised in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander understanding of social and emotional wellbeing and a community and government partnership sustainable across generations and beyond the life of this chapter.

Social and emotional wellbeing

Health is not just the physical wellbeing of an individual, but refers to the social, emotional and cultural well-being of the whole community. This is a whole of life view, and it also includes the cyclical concept of life-death-life. Health care services should strive to achieve the state where every individual can achieve their full potential as human beings and thus bring about the total well-being of their communities (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party 1989, p 10).

Fundamental principles

The nine guiding principles that follow have been extracted from Ways Forward (Swan & Raphael 1995) and further reiterate the unique diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, people, communities, needs and histories.

Any delineation of mental health problems and disorders must encompass recognition of the historical and socio-political context of Aboriginal mental health (Swan & Raphael 1995), including: the impact of colonisation; trauma, loss and grief; separation of families and children; the taking away of the land; loss of culture and identity; and the impact of social inequity, stigma, racism and ongoing losses.

Central to developing culturally safe practice and an understanding of social and emotional wellbeing are the guiding fundamental principles in the Ways Forward document, in which the full version of the principles can be found (Swan & Raphael 1995). For the purpose of this discussion, the principles have been shortened to capture the inherent notions and provide an overview:

These principles, derived from Ways Forward 1995, and the Social and Emotional Wellbeing Framework 2004–2009 (NATSIHC/NMHWG 2004), provide a five-year strategic plan that works towards improving the mental health and social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The Framework has been endorsed by the Commonwealth and state/territory governments, and represents agreement among a wide range of stakeholders on the broad strategies that need to be pursued.

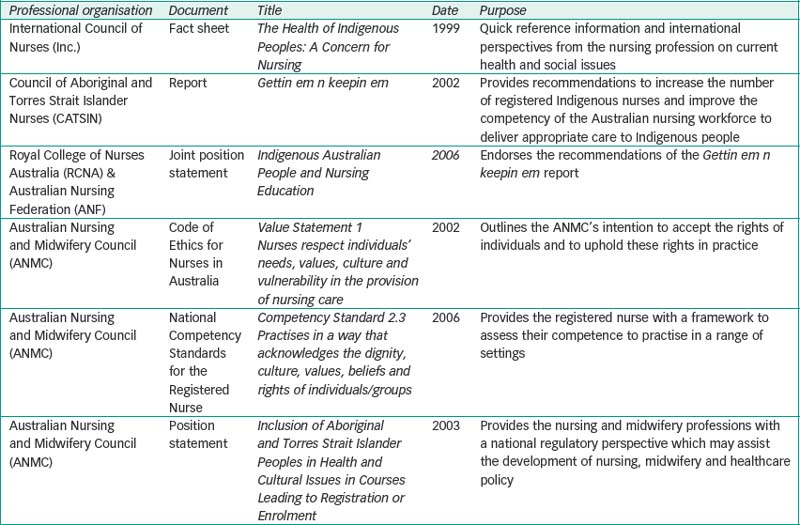

The documents in Table 7.1 provide guidelines for action for the education, development, recruitment and retention of Indigenous nurses and also guide the responses of all nurses to Indigenous health issues.

Critical thinking challenge 7.1

Are you familiar with any of the documents in Table 7.1? If not, take some time to read them and then explore how the documents influence your current nursing practice or studies.

The authors acknowledge that there are multitudes of challenges faced by nurses when working crossculturally with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people within the mental health arena. The following discussion, while limited, is provided to introduce the reader to issues that are considered pertinent when working within this context. It is hoped that these discussions will be the beginning of your journey of learning towards culturally safe nursing practice.

Communication

Principles of communication, including therapeutic relationship, transference and communication skills, are discussed in Chapter 23. The following discussion will focus on the factors that could potentially influence communication styles between the nurse and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient. Nurses need to understand what the effects of cross-cultural communication are on the therapeutic relationship, which is the foundation of mental health nursing. Greater understanding of the context of the underlying issues that have affected this will enhance the nurse’s ability to communicate in a culturally appropriate manner, which in turn will facilitate successful assessment and treatment for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient.

the impact of past government policies is vivid in the minds and lives of many Aboriginal people. Therefore, it is always important to remember that to a large proportion of Aboriginal people public servants are often perceived as representatives of large, powerful, unfriendly and uncaring bureaucracy due to the historical factors (DATSIP 2000, p 21).

Cultural safety

the effective nursing of a person/family from another culture by a nurse who has undertaken a process of reflection on his/her own cultural identity and recognises the impact of the nurse’s culture on his/her own nursing practice and also that unsafe cultural practice is any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual (Nursing Council of New Zealand 2002, p 1).

Box 7.1 lists the steps that nurses can take towards achieving cultural safety in practice.

Box 7.1 Steps to cultural safety

Source: Nursing Council of New Zealand 2002, p 9.

Time

Days, dates, hours, minutes, months and so on all provide us with some concept of time. In healthcare we are often ‘ruled’ by time … mane medication, 4/24 observations, counselling appointments weekly, visiting hours, meals arrive at set times, change of shift occurs at the same time of day. In almost every hospital in Australia, if not the world, healthcare services are governed by time. When considering the Indigenous concept of time we need to understand the potential implications for treatment outcomes. As Janca & Bullen (2003, p 41) suggest, ‘priorities take precedence over time. Family and community for an Aboriginal person are highly prioritised’.

A multidimensional view of time is possibly the easiest way to understand the differing view of time for an Aboriginal person. Janca & Bullen (2003, p 41) illustrate this by stating that ‘time is around you at every moment. You can’t pull time apart or separate it—in the abstract or when talking about it—from living, nor can it be viewed as purely functional groups of seconds, minutes and hours’.

When considering this view of time it is possible to foresee potential implications for healthcare outcomes. For example, what if you are living in a rural community and the mental health team visit monthly, but the night before the team is due to arrive there is a crisis in one of the local families? This crisis will take precedence over any healthcare appointments and therefore could affect the healthcare of the community and the people in it.

Psychopharmacology

The following discussion focuses on the potential issues that can be encountered when using medication with Indigenous people. (Psychopharmacology is discussed in detail in Ch 25; please refer to this chapter for specific information regarding medication and its use in psychiatry.) Nurses need to ask: How can we ensure the safe use of medication for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person with a mental illness? A complexity of issues need to be considered, including comorbidity, illicit drug use, access to medication, access to follow-up, nutrition, use of traditional medicines, sensitivity to medication and potential side effects (de Crespigny et al 2006). It is important to recognise that the issues listed are not exclusive to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and to understand that there are mitigating factors, as illustrated by the following scenario:

the safe use of medication it is vitally important to incorporate strategies to counteract the possible unsafe use of medication into care planning. As Kowanko et al (2004, p 253) state: ‘Evidence suggests that unsafe or inappropriate use of medicines is common, with potentially damaging physical, social and economic consequences’.