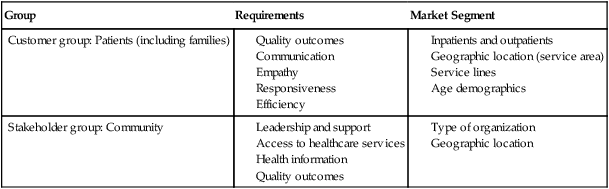

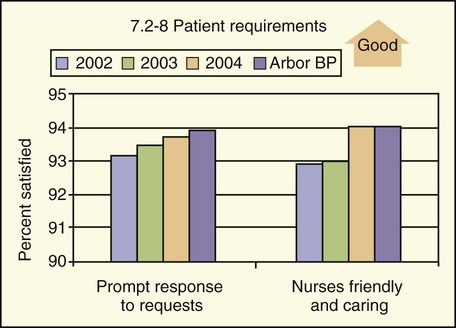

1. Identify the key focus of performance improvement. 2. Discuss trends in quality improvement. 3. List three drivers of quality. 4. Outline two models of performance improvement. 5. Identify three clinical outcome measures. 6. Identify major patient safety goals. 7. Describe four nursing outcomes specific to desired specialty. Set of nationwide goals set by The Joint Commission, to focus performance in areas of patient safety The year 1998 was a pivotal year in the quest for improvement in health care. In that year, the Institute of Medicine issued a report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, detailing the problem of medical errors in health care. The Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality also released a report calling for a national commitment to improve quality, concluding that “there is no guarantee that any individual will receive high quality care for any particular health problem … the health care industry is plagued … with errors in health care” (Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality, 1998). It was found that these quality concerns occur typically because of ways in which care is organized. Health care organizations were challenged to ensure that services were safe, effective, patient centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Health care costs became a major issue in the 1980s, and society began to question the efficiency and effectiveness of health care (Phelps, 1997). Health care administrators turned to industry for lessons learned in managing efficiency. Industry had adopted quality management techniques in the 1950s. An early proponent was W. Edwards Deming, who worked with the Japanese automotive industry after World War II. His 14-point management philosophy is the underpinning of TQM. The 14 points follow: 1. Create constancy of purpose toward improvement of product and service, with the aim to become competitive and to stay in business, and to provide jobs. 2. Adopt the new philosophy. We are in a new economic age. Western management must awaken to the challenge, must learn their responsibilities, and take on leadership for change. 3. Cease dependence on inspection to achieve quality. Eliminate the need for inspection on a mass basis by building quality into the product in the first place. 4. End the practice of awarding business on the basis of price tag. Instead, minimize total cost. Move towards a single supplier for any one item, on a long-term relationship of loyalty and trust. 5. Improve constantly and forever the system of production and service, to improve quality and productivity, and thus constantly decrease costs. 6. Institute training on the job. 7. Institute leadership. The aim of supervision should be to help people and machines and gadgets to do a better job. Supervision of management is in need of an overhaul, as well as supervision of production workers. 8. Drive out fear, so that everyone may work effectively for the company. 9. Break down barriers between departments. People in research, design, sales, and production must work as a team, to foresee problems of production and in use that may be encountered with the product or service. 10. Eliminate slogans, exhortations, and targets for the workforce asking for zero defects and new levels of productivity. Such exhortations only create adversarial relationships, as the bulk of the causes of low quality and low productivity belong to the system and thus lie beyond the power of the work force. a. Eliminate work standards (quotas) on the factory floor. Substitute leadership. b. Eliminate management by objective. Eliminate management by numbers, numerical goals. Substitute leadership. a. Remove barriers that rob the hourly paid worker of his right to pride in workmanship. The responsibility of supervisors must be changed from sheer numbers to quality. b. Remove barriers that rob people in management and engineering of their right to pride in workmanship. This means, abolishment of the annual or merit rating and management by objective. 13. Institute a vigorous program of education and self-improvement. 14. Put everybody in the company to work to accomplish the transformation. The transformation is everybody’s job (Deming, 2000a, pp. 23-24). Deming believed that an industry consists of multiple processes and decisions, which are interrelated, and developed a “system of profound knowledge” (Deming, 2000b): • All work consists of multiple processes • Differences in work are the result of the system of work, not individual worker performance • New work designs are based on our understanding of how work processes relate to one another His model for improvement was the PDCA (Plan–Do–Check–Act) cycle, which remains in widespread use today. Juran (1989) elaborated on Deming’s work in TQM. He believed that quality “did not happen by accident” but was the result of a quality trilogy—planning, control, and improvement. In 1960, Crosby defined quality as the extent to which processes were in conformance with the requirements of the customer. He was known for believing that things should be done “right the first time” and for the philosophy of “zero defects” (Nielson et al., 2004). While these three proponents of quality improvement focused on work processes, Donabedian (1992) contributed the idea of outcome as part of the overall quality structure. Outcomes involve the results achieved, and they reflect the effectiveness of the process components. This outcomes focus allows institutions to measure themselves against the standards and the competition. A compendium of past and present quality terms is presented in Table 10-1. Table 10-1 PAST, PRESENT, AND EVOLVING QUALITY TERMS Adapted from Yoder-Wise, P. (2003). Leading and managing in nursing (p. 175). St. Louis: MO: Mosby. This focus on outcomes has moved health care from a compliance model toward one of “best practice.” While accrediting bodies and federal regulators set minimum standards of compliance, many hospitals are now moving toward a model of “best in class.” Examples of organizations that recognize such “best practice” are American Nurses Association and its Magnet Award for Nursing and the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award for performance excellence. Hospitals winning the Magnet Award can be accessed at http://www.nursingworld.org/ancc/magnet/index.html. The hospitals that have been recognized by receiving the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award can be accessed at http://baldrige.nist.gov/Contacts_Profiles.htm. • Meeting and exceeding the needs of the customer • Building organizational learning into each work process • Continually evaluating and improving work processes • Assessing all customer requirements It is vital to remember that all PI must be “data driven” and not based on anecdote. Obviously, the key customers of health care are the patient and family; they are at the center of all drivers of quality. Other customers of the hospital include the physicians and the community. Bronson Methodist Hospital in Kalamazoo, Michigan, has defined the patient (and family) and the community as key customers, with key requirements and market segments as given in Table 10-2. Table 10-2 KEY CUSTOMER AND STAKEHOLDER GROUPS, REQUIREMENTS, AND MARKET SEGMENTS From Bronson Methodist Hospital. (2007). Baldrige application. Retrieved March 11, 2007, from http://baldrige.nist.gov/PDF_files/Bronson_Methodist_Hospital_Application_Summary.pdf. Patient care units have an abundance of data available to them. One common outcome used by patient care units is patient satisfaction. A majority of health care organizations across the United States measure patient satisfaction. Two of the common vendor satisfaction measures are Press Ganey and Gallup. These data can be segmented to list the performance of specific units/shifts. The key requirements of the patient/family at Bronson Methodist Hospital are listed in Box 10-2. They were identified as: communication, empathy, responsiveness, and efficiency. Patient satisfaction surveys are customized to include information on the key requirements of the patients of an institution. With the use of nationwide surveys, hospitals can compare their performance with that of other local hospitals, of similar hospitals, and of best-in-class performers. See Figure 10-1 provides an example of a patient satisfaction data set. Other data sets available to the nurse include the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators® (NDNQI®), a program of the American Nurses Association National Center for Nursing Quality. The database collects and evaluates unit-specific nurse-sensitive data from hospitals in the United States and internationally. Participating facilities receive unit-level comparative data reports to use for QI purposes. Nursing-sensitive indicators reflect the structure, process, and outcomes of nursing care (Box 10-1) (National Center for Nursing Quality, 2007).

Improving Organizational Performance

IMPROVING ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Past Quality Terms

Present Quality Terms

Evolving Quality Terms

Quality control

Total quality management

Quality management

Quality assurance

Continuous quality improvement

Quality improvement

Performance improvement

Performance excellence

KEY FOCUS OF PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT

DRIVERS OF QUALITY

Group

Requirements

Market Segment

Customer group: Patients (including families)

Stakeholder group: Community

OUTCOME MEASURES

Example of a patient satisfaction data set. This graph shows that in 2002, 93.3% of patients thought that nurses promptly responded to their needs, and that in 2004, this increased to 94%. The local best practice was 94. Arbor BP, Arbor Best Practice.

Improving Organizational Performance

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access