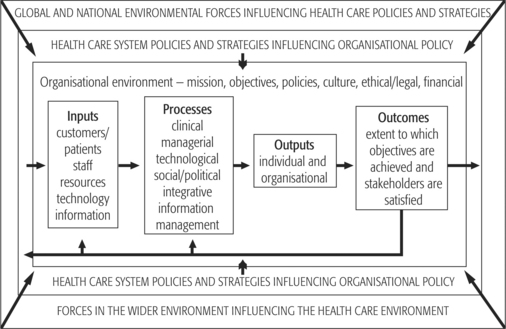

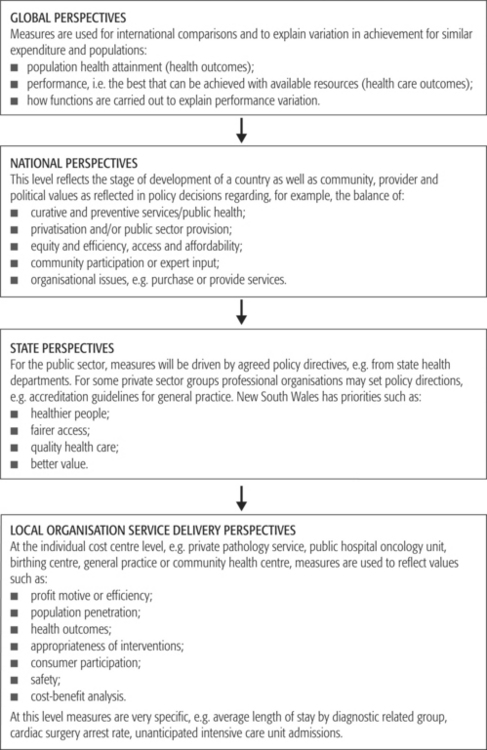

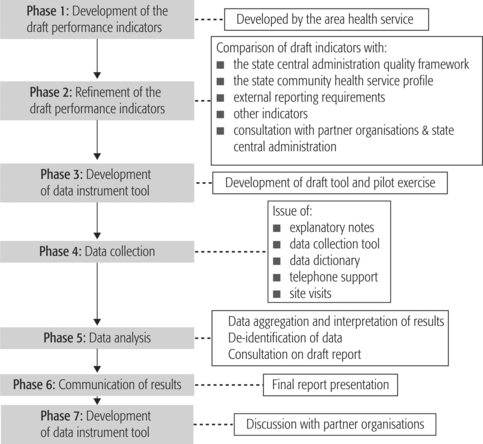

CHAPTER 15 Improving organisational performance in health care After studying this chapter, the reader should be able to: Performance improvement initiatives may occur at various levels, including local organisations, specified geographic or administrative regions (e.g. area health service or state), and national and international levels. The aim and focus of measurement varies accordingly. Any bid to improve organisational performance in health requires identification of key values that underpin service delivery. Each country and community has its own historical, political, geographic and economic reasons for providing health services the way they do. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are collaborating to identify health attainment in various countries and to explain differences in performance between similar nations with a view to improving the performance of all systems (WHO 2000a). Importantly, the WHO year 2000 annual report acknowledges the contribution to health care systems performance of factors other than health service provision. This has led to debate about measuring performance and further refinements of the proposals. As indicated in Chapters 1 and 2, the job of the health service manager is to contribute to the enhancement of organisational performance. This applies at all levels and in all spheres of management. Like organisations in other industries, all health care organisations consist of a number of ‘responsibility centres’, variously referred to as departments, teams, units, etc (Anthony & Herzlinger 1980, p 2). The relevant manager is held responsible for what the centre does and the resources it uses. As indicated in Chapters 11 and 12, despite differences in the structure of individual centres (e.g. functional, divisional, product line, matrix) their common purpose is to contribute to the performance of the organisation of which they are part and ultimately to the performance of the health system. The United States Institute of Medicine (1997, p 1) defined organisation performance improvement as: Figure 15.1 outlines a systems approach to organisational performance. This figure indicates the importance of considering the context (or environment) for organisational performance analysis. As indicated in Chapter 4, contextual considerations include the social, economic and technological environment in which the organisation operates and the policy, administrative and cultural environment, including global and national health care system performance measurement trends. The latter are explored in this chapter. Figure 15.1 also indicates that organisational performance can be measured in terms of inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes. The emphasis placed on each of these domains may change over time and will depend to a large extent on the level of analysis, the prevailing values and priorities of those with authority, the availability of reliable and appropriate data and the capacity of managers to use the data (see Chapters 10 and 18). For example, a private health care facility is likely to place great emphasis on shareholder value and will probably use different financial performance measures from those of a not-for-profit voluntary health care facility or a public sector health service facility. With respect to financial performance, the latter are likely to emphasise budgetary control measures. The quest to improve organisational performance in health care raises questions of definition, content and measurement. Figure 15.2 indicates how measures of performance vary according to the level of analysis. For example, global initiatives are largely concerned with the comparison of national health systems, in terms of population health status and expenditure, and explanations of variations in performance among countries. A worldwide framework for performance in health care was published by WHO (2000a) in its annual report. This framework seeks to measure attainment of key goals and the design and core functions performed by health systems that may explain goals achievement. Key goals specified in the WHO (2000a, p xi) World Health Report are: National measurement relates to the achievement of specific goals and targets in national policy and planning. National health goals and targets are affected by the stage of economic development of the country, past history, community, provider and political values (see Figure 15.2). Differences between nations emerge following consideration of public or private provision, balance of preventive and curative services, equity and efficiency issues, services provided, their financing, distribution and organisation. According to George and Davies (1998, p 98), organisation affects access, costs of the system, where costs are borne and outcomes. Some examples of services organisation are discussed in the next section. In the public health care system in Australia (local, state, territory, regional or service delivery network) measures of performance derive from policy. For example, in New South Wales, performance agreements ensure a link between state policy and regional (or area health service) performance. In the private sector the performance of smaller organisations (e.g. private hospitals) is consistent with the priorities of the corporation, although constrained by government policy. As indicated in Figure 15.2, the specificity of performance measurement is directly proportional to proximity to service provision. Performance measures for services reflect policy, but are also related to specific health problems, disease groups and service delivery values. Patient care performance measures ascertain the degree to which what is done for the patient is: Furthermore, in attaining acceptable patient care performance, the organisation must at the same time achieve business and other financial targets. As in all areas of management, approaches to improving organisational performance in the health industry are continually evolving. This process of evolution is reflected in terms such as ‘quality assurance’, ‘total quality management’, ‘best practice’, ‘benchmarking’, ‘shareholder value’, ‘balanced scorecard’, ‘risk management’, ‘evidence-based decision-making’, ‘clinical governance’ and ‘learning organisation’. Chapter 16 addresses the first two of these concepts, while risk management and clinical governance are examined in Chapter 17. Here the emphasis is on best practice, benchmarking and achieving a balanced approach to the measurement of organisational performance. Best practice has been defined by the National Health Performance Committee (2000, p 59) as: Benchmarking is defined by the National Health Performance Committee (2000, p 59) as: The effectiveness of benchmarking is increased when it is an ongoing process, is incorporated into the management information systems of an organisation so that the data-capture processes do not require special programming or separate coding, where the costs can be shared or spread across departments or organisations, and where historical benchmarks can be adjusted to current conditions (Weller & Sayegh 1998, p 41). Dervitsiotis (2000, p S641) suggests that: The Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal of New South Wales (IPART) (1998, p 106), in considering the organisational performance of the New South Wales health system, suggested that benchmarking was useful for: This same report (IPART 1998, p 107) suggested that good managers do not need voluminous pages of performance information. Rather they need illustrated brief exception reports that are timely and accurate; such reports are sufficient to enable superior management. An exception is a report that addresses exceptional events or performance (i.e. deviations from accepted practice or acceptable performance). These exceptions may be good or bad. It goes on to suggest that well-chosen measures (i.e. key performance indicators) allow management to focus on those areas where it is critical to improve and maintain performance. The IPART report also suggests that for performance measurement to be successful, key performance indicators must: Critics have suggested that managers waste time and money on external benchmarking when their best practices are better than that of the average practices of the ‘best companies’ and that there are greater benefits for them in an internal exercise. Moreover, internal benchmarking is more easily achieved (Puckett & Siegel 1997, p 12). However, many health care organisations benchmark externally. For some elements of performance they benchmark with organisations within the health industry and for others with service organisations in other industries. Curley (2000) asserts that in health service organisations scientific inquiry and benchmarking are becoming a driving force for change. He maintains that: For best practice and benchmarking programs to work in any context they need to be implemented into an appropriate organisational culture. Furthermore, the uses and limitations of these methodologies need to be understood by all who are to be affected by it. Where performance improvement programs have been initiated in an accreditation and/or quality management framework and the focus has been on outcomes, they have usually been effective in empowering staff, developing teamwork and committing an organisation to continuous learning and improvement. Table 15.1 outlines some of the changes in organisational culture that may be required to support an effective performance management system. Table 15.1 Developing an appropriate culture to support an effective performance management and best practice system Source: Adapted from Glass P 1998 A benchmarking intervention into executive teams (government agencies). Total Quality Management 9(6): 519 The New South Wales Corrections Health Service (2000, pp 3, 4), subsequently renamed Justice Health, provides a useful example of benchmarking (Figure 15.3). This organisation delivers health services to the inmates of the state’s prisons. It embarked on a benchmarking program because it was seen as ‘… a method of continuous improvement that involves an ongoing and systematic evaluation and incorporation of services, processes and outcomes recognised as representing best practice’. In benchmarking with a group of health, psychiatric, forensic and corrective services in Australia and New Zealand, this health service sought to: The balanced-scorecard approach recognises a range of stakeholders with differing interests and provides measures that allow for various perspectives to be taken into account, thereby giving a ‘balanced’ approach to performance measurement. Performance indicators include the views of customers, financial indicators, internal business indicators and measures of organisational innovation and learning (Hubbard 2000, p 102). Gearhart (1999, p 13) supports a balanced approach to performance monitoring and improvement in the public sector. He maintains that measures of performance should provide strategic information and operational information (see Table 15.2) that allows the organisation to engage in benchmarking with other high-performing organisations. A balanced performance system is one that provides a picture of how the organisation is currently performing and supports decisions about: Table 15.2 A performance measurement framework Source: Adapted from: Weller AO, Sayegh AWL 1998 Benchmarking tools for public risk management programs. Government Finance Review 14(5): 41 According to Gearhart (1999), this approach allows for the allocation of resources to the most strategic aspects of the business and improved operational control by targeting the activities, department or processes that are most inefficient and which have potential to re-engineer the processes or redesign structures to provide cost reduction and/or improve service. This organisation (Uniting Care) has recognised that in achieving balance in its approach to performance assessment and improvement the use of clinical indicators alone is not sufficient and is involved with others to research quality of life indicators and their relationship with quality of care indicators. Achieving a balanced approach to assessing organisational performance is no easy task in the health industry. One-dimensional financial performance indicators associated with measures of efficiency are often well developed, and managers recognise their value. On the other hand, measures of effectiveness associated with clinical services to patients and communities are generally seen as the domain of clinical staff. It is therefore not surprising that the two are rarely aligned. In a relatively simple way, Case Study 15.1 seeks to demonstrate the challenges of achieving a balanced approach to assessing and improving organisational performance. CASE STUDY 15.1 TOWARDS A BALANCED APPROACH TO ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT Source: Adapted from Healey T 2000 Observations and experience as to how residential aged care can and cannot work. How to develop and maintain facilities. Second International Aged Care Housing Summit 2000, Melbourne; Briggs DS 2001 Using financial and non-financial performance measures to determine the true performance of your aged care facility. Performance Measures for Retirement Villages and Aged Care Facilities Conference — International Quality and Productivity Centre, Sydney

Define theories and concepts underpinning organisational performance improvement practices in health care.

Define theories and concepts underpinning organisational performance improvement practices in health care.

Demonstrate understanding of the steps required to implement a process for improving organisational performance.

Demonstrate understanding of the steps required to implement a process for improving organisational performance.

Describe the advantages and limitations of standardised measures used to assess organisational performance.

Describe the advantages and limitations of standardised measures used to assess organisational performance.

INTRODUCTION

ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT AND MANAGEMENT THEORY AND PRACTICE

Four levels of performance measurement

APPROACHES TO IMPROVING ORGANISATIONAL PERFORMANCE

Best practice

Benchmarking

internal benchmarking is more valuable than external benchmarking because there can be as much as 20 to 30 per cent difference for critical performance indicators between the best and the average performance within the same organisation;

internal benchmarking is more valuable than external benchmarking because there can be as much as 20 to 30 per cent difference for critical performance indicators between the best and the average performance within the same organisation;

process benchmarking is the most appropriate form of benchmarking, as it has to do with easily measurable aspects of a company’s operation;

process benchmarking is the most appropriate form of benchmarking, as it has to do with easily measurable aspects of a company’s operation;

benchmarking is best suited to high-performance companies that are attuned to the need to adapt to best practice;

benchmarking is best suited to high-performance companies that are attuned to the need to adapt to best practice;

medium- and low-performance organisations could benefit more from simpler, faster and less costly improvement efforts, such as developing better knowledge in relation to their customers and employees;

medium- and low-performance organisations could benefit more from simpler, faster and less costly improvement efforts, such as developing better knowledge in relation to their customers and employees;

benchmarking points the way to incremental improvements that in time become smaller while the organisation remains in the same strategic operating paradigm; and

benchmarking points the way to incremental improvements that in time become smaller while the organisation remains in the same strategic operating paradigm; and

benchmarking is useful for incremental improvement in situations where an organisation is already successful.

benchmarking is useful for incremental improvement in situations where an organisation is already successful.

identifying role models to serve as benchmarks for a program of process benchmarking to lift performance;

identifying role models to serve as benchmarks for a program of process benchmarking to lift performance;

identifying area health services and/or health care facilities that are the most efficient at providing particular services;

identifying area health services and/or health care facilities that are the most efficient at providing particular services;

analysing the extent to which best practice clinical pathways overcome diseconomies of small size; and

analysing the extent to which best practice clinical pathways overcome diseconomies of small size; and

analysing how differences in the operating environment can be accounted for when evaluating performance.

analysing how differences in the operating environment can be accounted for when evaluating performance.

represent a small number of complementary measures, which reflect actual performance against the primary objectives of the entity;

represent a small number of complementary measures, which reflect actual performance against the primary objectives of the entity;

be balanced to adequately reflect the three perspectives of (1) finance and budgets, (2) quality and access, and (3) productivity.

be balanced to adequately reflect the three perspectives of (1) finance and budgets, (2) quality and access, and (3) productivity.

FROM

TO

A technological outlook

Customer outlook

Operational short term

Strategic long-term planning

Internally focused

Externally focused

Trying to do everything

Concentrating on what you do best

A parochial view

Corporate view

Lack of competitive incentive

External competition

Procedural

Innovative and flexible

Rewards constrained by public service conditions and awards

Rewards and payments based on performance, commitment and contribution

Balance in the use of performance indicators

PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT MEASURES

BENEFITS OF PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT

FRAMEWORK FOR FUTURE ACTION

Financial

Strategic information

Where should resources be allocated?

Customer

Accurate information

Which customers should be served?

Internal

Operational benchmarks

What delivery mechanism makes sense?

Innovation and learning

Expenditure versus revenue analysis

How can we do it better next time?

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Improving organisational performance in health care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access