Chapter 13 Immune Health Breakdown

When you have completed this chapter you will be able to

INTRODUCTION

Specific learning exercises are listed at the end of each major subsection of this chapter.

THE NORMAL IMMUNE SYSTEM

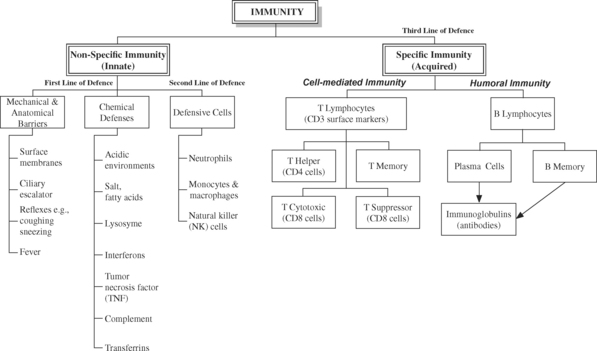

Our bodies are constantly under threat of disease from external (e.g., bacterial and viral invasion) and internal (e.g., mutated cells such as cancerous cells) sources. If external invaders break through the first line of defence (e.g., anatomical barriers such as skin and mucosae), they encounter a second line of defence in the form of phagocytic cells and face death by toxic chemical assault. This is part of the inflammatory response that occurs whenever there is tissue damage, no matter the cause. Inflammation is a non-specific defence mechanism – if a cell or particle is detected as being damaged, infected, or otherwise ‘not belonging’, no matter how or why, it is considered hostile and is immobilised, destroyed and removed. The phagocytic cells of the non-specific defence mechanism also take chemical instructions from the much fussier specific defence mechanism, which is the third line of defence. All components of the non-specific immune system are modulated by products of the specific immune system, such as interleukins (IL), alpha and gamma interferon and antibodies (see Figure 13.1).

Balance and control of the immune system is critical for survival – hypersensitivities (allergies) and autoimmune disorders can result from an over-vigilant, over-responsive immune system, while immunodeficiency syndromes and increased susceptibilities to infections are typical of an under-active immune system. Immune activity is also influenced by activity of the neuroendocrine system, and thus subject to the influence of neural activity, neurotransmitters and hormones.

At 36 hours, John’s capillary seal is regained but he shows signs of acute pulmonary oedema. He has an external anteriovenous (AV) shunt1 inserted and commences haemodialysis in order to maintain fluid and electrolyte balance while his kidneys convalesce from prerenal acute renal failure (ARF). (John’s case will be reconsidered later in the chapter to address the immunological aspects of organ transplantation).

What are the basic prerequisites for a healthy inflammatory response?

When tissue damage is extensive, the metabolic demands of the body for the inflammatory response and healing purposes can more than double. Unless protein supply matches demand, the body will rapidly catabolise (breakdown) muscles (including the diaphragm in severe cases), and recycle the amino acids to form more urgently-needed proteins such as albumin, fibrin, clotting factors, collagen and immunoglobulins. Matching supply with demand can be challenging, and critically ill patients often require Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) in addition to enteral feeds.

Compared to non-smokers, the healing time for smokers is slow. Nicotine impedes the delivery of oxygenated blood by causing vasoconstriction, and chronic exposure to nicotine causes T cell unresponsiveness2,3,4.

Why was John at risk of developing pulmonary oedema? John was susceptible to developing pulmonary oedema for several reasons. In burns and most other tissue damage situations, the greater the tissue damage the greater the inflammatory response. As a result of the increase in capillary permeability, fluids and even proteins escape into the interstitium, causing widespread oedema. When the capillary seal is regained, excess interstitial fluid is drained by the lymphatics and returned to the cardiovascular system. This adds to the workload of the heart and kidneys, and during this period pulmonary oedema may occur.

The immune system constantly treads a fine line between being over-vigilant and hyper-responsive (resulting in hypersensitivity and autoimmune disorders), and under-active and hypo-protective (resulting in immunodeficiency syndromes and a heightened susceptibility to infections and cancer). Appropriate balance and coordination between the various elements of the immune system, including appropriate levels of cellular activity, cytokine release and hypothalamic function are of the essence for normal function5.

NON-SPECIFIC IMMUNITY – FIRST AND SECOND LINES OF DEFENCE

The three major elements of non-specific immunity are

Intubation temporarily hampers or renders useless ciliary function. Ciliary damage can be acquired, such as through inhaling cigarette smoke.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia is a genetic disorder (thought to be caused by mutation of a single gene, inherited in an autosomal recessive manner), where ciliary motion is erratic and uncoordinated6. Affected individuals have a lifetime history of chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, chronic cough, and recurrent pneumonia.

Low NK cell activity seems to be associated with stress9 of any type, poor nutrition, overwork, acute or chronic disease, emotional trauma and bereavement.

HEALING AND THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

WHY THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE IS IMPORTANT TO SURVIVAL

Whenever there is tissue damage, be it from a period of hypoxia (e.g., myocardial infarction), physical trauma (e.g., traumatic brain injury) or invasion by a pathogen (infection), the innate and non-specific response of the body is to inflame the affected area. Inflammation is the process by which the body attempts to heal itself, and essentially consists of two stages:

PRO-INFLAMMATORY CHEMICALS DURING INFLAMMATION

WHAT IS THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY?

The relationship between the physiological events involved in inflammation, the clinical manifestations and the beneficial effects of the inflammatory process are shown in Table 13.1.

TABLE 13.1 PHYSIOLOGICAL EVENTS UNDERLYING THE CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND BENEFITS OF INFLAMMATION

| Underlying Physiology | Clinical Manifestation | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Redness | ||

1. Increased metabolic activity by leucocytes and fibroblasts → an increase in the production of heat as a waste product of biochemical reactions → local warmth | Warmth | 1. If microorganisms are present, the local increase in temperature may inhibit their growth or make them more vulnerable to attack |

| Cytokines (especially histamine and PG) increase capillary permeability, making them more “leaky”. The increased volume of interstitial fluid is oedema | Oedema | The influx of fluid dilutes: |

1. Inflammatory cytokines (especially PG and BK) are released from damaged cells → irritate sensory nerves → perceived as pain | Pain | |

| Loss of function | 1. Inhibits movement and limits further damage |

HOW SCAR TISSUE IS FORMED

Excessive production of collagen leads to the formation of a raised keloid scar. Trauma to the skin, both physical (e.g., surgery) and pathological (e.g., lesions arising from acne vulgaris and varicella (i.e., chickenpox) is the primary cause identified for developing keloids. There are also familial tendencies and racial differences in the prevalence of keloid formation. The highest incidence of keloid scarring occurs in black Africans. The genetics of keloid formation are currently under investigation, and several genes seem to be involved10,11.

DAMPENING THE INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE

Acute anaphylaxis12 refers to a severe allergic reaction to a foreign protein or molecule such as penicillin, IV contrast media, bee or wasp venom, and certain foods (most notably, peanuts). Upon a second exposure to the allergen sensitised mast cells and basophils release large amounts of histamine. A cascade of biochemical and physiological events follows, which includes the involvement of many pro-inflammatory chemicals including PG and LT. Excessive vasodilation and increased capillary permeability lead to a dramatic drop in blood pressure, while bronchial smooth muscle contraction, airway oedema and mucus production cause acute respiratory distress.

In addition to providing support for the respiratory system (assisted ventilation, intubation) and cardiovascular system (IV fluids), the primary drug treatments for acute anaphylactic reactions are IV adrenaline and H1 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl, Unisom). (Corticosteroids are mainly effective in preventing biphasic i.e. delayed reactions, and are not considered as a first-line treatment).

OTHER INFLAMMATORY DRUGS IN THE REDUCTION OF INFLAMMATION

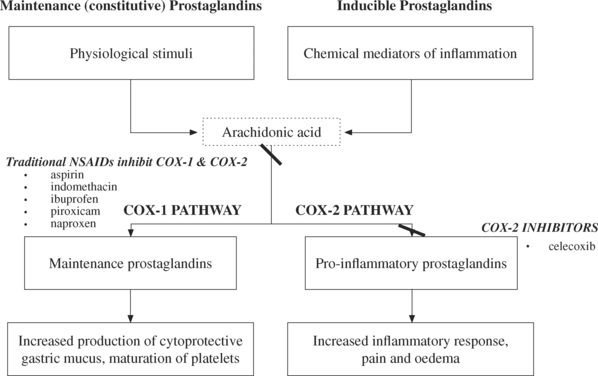

In Australia there are over 8 million prescriptions annually for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)13; these drugs work by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), and in so doing, decrease the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Some types of prostaglandins (those involved in the COX-1 pathway) are needed on a continuous basis and are stimulated by routine physiological events. The COX-1 prostaglandins stimulate physiological body functions, such as the production of protective gastric mucus and platelet maturation.

Older NSAIDs such as aspirin (Asprin), indomethacin (Indocid), ibuprofen (Nurofen) and naproxen (Naprosyn, Naprogesic) inhibit both COX-1 and COX-2 pathways, thus lowering the production of the maintenance and pro-inflammatory prostaglandins. While the anti-inflammatory benefits come from the inhibition of the COX-2 pathway, many of the undesirable effects (such as susceptibility to gastric erosion) result from blockade of the COX-1 pathway. Second-generation NSAIDs such as celecoxib (Celebrex), selectively inhibit the COX-2 pathway (expressed in synovial cells and macrophages), and are thus becoming popular for the symptomatic control of arthritis, sports injuries and other forms of inflammation (see Figure 13.2).

Note that celecoxib (Celebrex) has a marked capacity for allergy owing to its sulphonamide structure14.

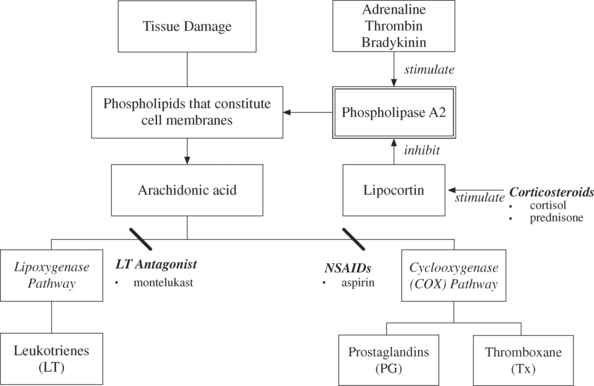

The anti-inflammatory corticosteroids such as cortisol and prednisone inhibit the activation of phospholipase A2 by causing the synthesis of an inhibitory protein called lipocortin. It is lipocortin that inhibits the activity of phospholipases and therefore limits PG production15 (see Figure 13.3). Steroids also impair lymphocyte function, which results in the production of less IL. This reduces communication between lymphocytes and lymphocyte proliferation. Hence, people on steroids long term have an increased susceptibility to infection.

Paracetamol (Panadol, Pamol) may inhibit PG centrally rather than peripherally. It is analgesic and antipyretic but not an anti-inflammatory drug16.