I

Increased intracranial pressure

Description

Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is a potentially life-threatening situation that results from an increase in any or all of the three components within the skull: brain tissue, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

Pathophysiology

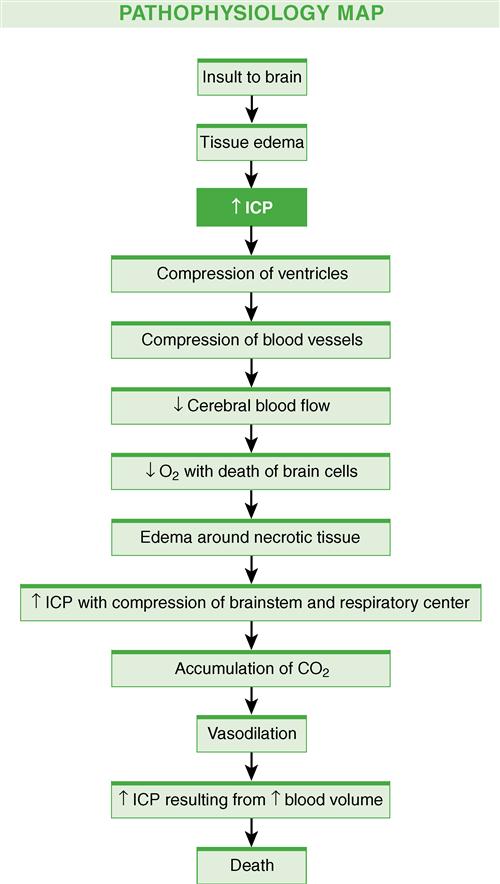

Common causes of increased ICP include a mass lesion (e.g., hematoma, contusion, abscess, tumor) and cerebral edema (associated with brain tumors, hydrocephalus, head injury, or brain inflammation). These cerebral insults, which may result in hypercapnia, cerebral acidosis, impaired autoregulation, and systemic hypertension, increase the formation and spread of cerebral edema. This edema distorts brain tissue, further increasing the ICP, and leads to even more tissue hypoxia and acidosis.

Regardless of the cause, cerebral edema results in an increase in tissue volume that has the potential to increase ICP. The extent and severity of the original insult are factors that determine the degree of cerebral edema. Figure 9 illustrates the progression of increased ICP.

There are three types of cerebral edema, including vasogenic, cytotoxic, and interstitial. More than one type may occur in the same patient.

Clinical manifestations

Manifestations of increased ICP can take many forms, depending on the cause, location, and rate of increase of ICP.

The major complications of uncontrolled increased ICP are inadequate cerebral perfusion and cerebral herniation.

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

The goals of management of increased ICP are to identify and treat the underlying cause of increased ICP and to support brain function. The earlier the condition is recognized and treated, the better the patient outcome. A careful history is an important diagnostic aid that can direct the search for the underlying cause.

Ensuring adequate oxygenation to support brain function is important. Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis guides the oxygen therapy. To meet the goal of maintaining the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) at 100 mm Hg or greater and to keep PaCO2 in normal range at 35 to 45 mm Hg, an endotracheal tube or tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation may be necessary.

■ If the condition is caused by a mass lesion, such as a tumor or hematoma, surgical removal of the mass is the best management (see Brain Tumors, p. 85).

Drug therapy

Drug therapy plays an important part in the management of increased ICP.

Nutritional therapy

The patient with increased ICP is in a hypermetabolic and hypercatabolic state that increases the need for glucose to provide the necessary fuel for metabolism of the injured brain. If the patient cannot maintain an adequate oral intake, other means of meeting the nutritional requirements, such as enteral or parenteral nutrition, should be started. Current fluid therapy is directed at keeping patients normovolemic.

Nursing management

Goals

The overall goals are that the patient with increased ICP will have ICP within normal limits, maintain a patent airway, demonstrate normal fluid and electrolyte balance, and have no complications secondary to immobility and decreased LOC.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

Respiratory function.

Maintenance of a patent airway is critical in patients with increased ICP and is a primary nursing responsibility. As the LOC decreases, the patient is at increased risk of airway obstruction.

■ In general, any patient with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 or less (see Glasgow Coma scale, p. 766) or an altered LOC who is unable to maintain a patent airway or effective ventilation needs intubation and mechanical ventilation.

■ Prevent hypoxia and hypercapnia. Proper positioning of the head is important.

Fluid and electrolyte balance.

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances can have an adverse effect on ICP. Closely monitor IV fluids. Intake and output, with insensible losses and daily weights taken into account, are important parameters in the assessment of fluid balance.

■ Electrolyte determinations should be made daily. It is especially important to monitor serum glucose, sodium, potassium, magnesium, and osmolality. Monitor urinary output for problems related to syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) and diabetes insipidus (DI) (see Diabetes Insipidus, p. 173).

Monitoring intracranial pressure.

ICP monitoring is used in combination with other physiologic parameters to guide the care of the patient and assess the patient’s response to routine care. Valsalva maneuver, coughing, sneezing, hypoxemia, and arousal from sleep are factors that can increase ICP. Methods of monitoring ICP are discussed in detail in Chapter 57, Lewis et al, Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed 9. Also see Intracranial Pressure Monitoring, p. 770.

Body position.

Maintain the patient with increased ICP in the head-up position. Take care to prevent extreme neck flexion, which can cause venous obstruction and contribute to elevated ICP. Adjust the body position to decrease the ICP maximally and to improve cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP).

Protection from injury.

The patient with increased ICP and a decreased LOC needs protection from self-injury. Confusion, agitation, and the possibility of seizures increase the risk of injury. Use restraints judiciously in the agitated patient. The patient can benefit from a quiet, nonstimulating environment. Touch and talk to the patient, even one who is in a coma.

Psychologic considerations.

Anxiety over the diagnosis and prognosis for the patient with neurologic problems can be distressing to the patient, caregiver, family, and nursing staff. Short, simple explanations are appropriate and allow the patient and family to acquire the amount of information they desire. There is a need for support, information, and education of both patients and families.

Assess the family members’ desire and need to assist in providing care for the patient and allow for their participation as appropriate.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Description

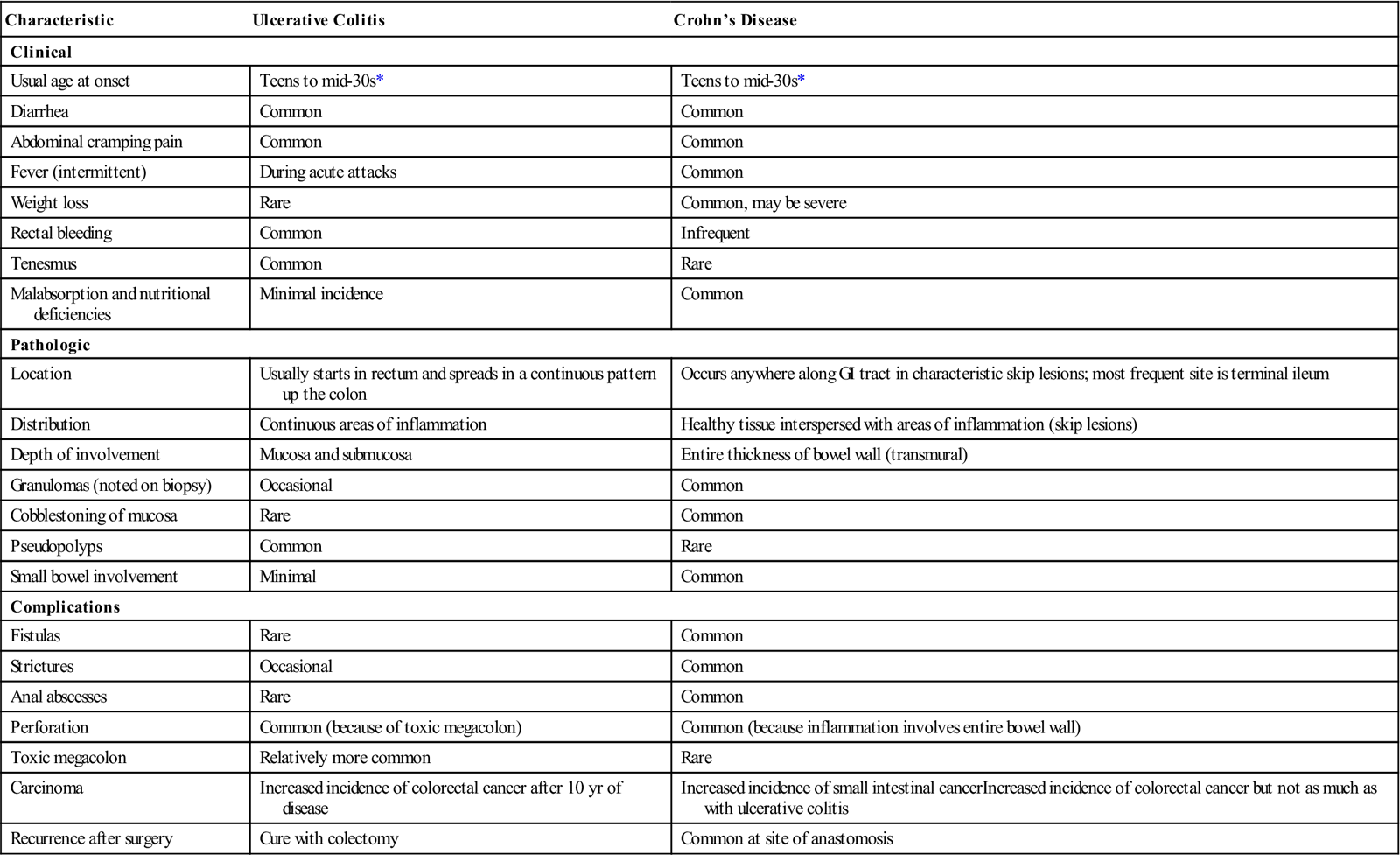

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammation of the GI tract. It is characterized by periods of remission interspersed with periods of exacerbation. The cause is unknown, and there is no cure. IBD is classified as either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis based on clinical manifestations (Table 53). Ulcerative colitis is usually limited to the colon. Crohn’s disease can involve any segment of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus.

Table 53

Comparison of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease

| Characteristic | Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease |

| Clinical | ||

| Usual age at onset | Teens to mid-30s* | Teens to mid-30s* |

| Diarrhea | Common | Common |

| Abdominal cramping pain | Common | Common |

| Fever (intermittent) | During acute attacks | Common |

| Weight loss | Rare | Common, may be severe |

| Rectal bleeding | Common | Infrequent |

| Tenesmus | Common | Rare |

| Malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies | Minimal incidence | Common |

| Pathologic | ||

| Location | Usually starts in rectum and spreads in a continuous pattern up the colon | Occurs anywhere along GI tract in characteristic skip lesions; most frequent site is terminal ileum |

| Distribution | Continuous areas of inflammation | Healthy tissue interspersed with areas of inflammation (skip lesions) |

| Depth of involvement | Mucosa and submucosa | Entire thickness of bowel wall (transmural) |

| Granulomas (noted on biopsy) | Occasional | Common |

| Cobblestoning of mucosa | Rare | Common |

| Pseudopolyps | Common | Rare |

| Small bowel involvement | Minimal | Common |

| Complications | ||

| Fistulas | Rare | Common |

| Strictures | Occasional | Common |

| Anal abscesses | Rare | Common |

| Perforation | Common (because of toxic megacolon) | Common (because inflammation involves entire bowel wall) |

| Toxic megacolon | Relatively more common | Rare |

| Carcinoma | Increased incidence of colorectal cancer after 10 yr of disease | Increased incidence of small intestinal cancerIncreased incidence of colorectal cancer but not as much as with ulcerative colitis |

| Recurrence after surgery | Cure with colectomy | Common at site of anastomosis |

Both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease commonly occur during the teenage years and early adulthood, and both have a second peak in the sixth decade. IBD is more prevalent in industrialized countries and in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. Many people with IBD have a family member with the disorder.

Pathophysiology

IBD is an autoimmune disease involving an immune reaction to a person’s own intestinal tract. Some agent or a combination of agents triggers an overactive, inappropriate, sustained immune response. The resulting inflammation causes widespread tissue destruction.

Evidence suggests that IBD is caused by a combination of factors, including environmental factors, genetic predisposition, and alterations in the function of the immune system. The pattern of inflammation differs between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

Crohn’s disease

The inflammation in Crohn’s disease involves all layers of the bowel wall and can occur anywhere in the GI tract from the mouth to the anus. It most commonly occurs in the terminal ileum and colon. Segments of normal bowel can occur between diseased portions, the so-called skip lesions.

■ Strictures at the areas of inflammation may cause bowel obstruction.

Ulcerative colitis

Ulcerative colitis usually starts in the rectum and moves in a continual fashion toward the cecum. Although mild inflammation sometimes occurs in the terminal ileum, ulcerative colitis is a disease of the colon and rectum.

Clinical manifestations

Symptoms are often the same (diarrhea, bloody stools, weight loss, abdominal pain, fever, and fatigue) in both conditions. Bloody stools are more common with ulcerative colitis, and weight loss is more common in Crohn’s disease because inflammation of the small intestine impairs nutrient absorption. Both forms of IBD are chronic disorders with mild to severe acute exacerbations that occur at unpredictable intervals over many years.

Crohn’s disease

Diarrhea and colicky abdominal pain are common symptoms of Crohn’s disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree