SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

• History of hygiene care practices in society

• The impact of individual, cultural and spiritual beliefs on individual hygiene practices

CARE DELIVERY KNOWLEDGE

• Assessment of an individual’s hygiene needs in relation to care of the body, mouth, hair and eyes

• Assessment tools and oral care

• Differing modes of delivery of hygiene care for all body parts

PROFESSIONAL AND ETHICAL KNOWLEDGE

• Ritualization of hygiene care

• Hygiene care and the image of the nurse

• Consent and privacy

• The politics of hygiene care

PERSONAL AND REFLECTIVE KNOWLEDGE

• Personal hygiene in the role of the nurse

• Reflection and experiential exercises

• Consolidation of learning through case studies

INTRODUCTION

Maintaining hygiene according to one’s personal and cultural norms is a basic human need. Helping individuals maintain their own hygiene is recognized as a fundamental role for the nurse. In partnership with the client and/or carer, the nurse is the primary decision maker in this area of healthcare practice. Responsibility for promoting and maintaining excellence in the quality of hygiene care is a key function of nursing (Badham et al 2006). However, the role of the nurse in the actual delivery of care will alter depending upon the particular context in which hygiene care is provided and the specific needs of the individual. The term ‘hygiene care’, used throughout this chapter, is often employed interchangeably with the term ‘personal care’ or ‘personal body care’.

Children and teenagers need varying levels of support and teaching to help them meet their hygiene needs. Health education for the child and the family is important in any context. Children and adults with deficits in learning ability need extra encouragement, time and teaching in order to meet their needs. For the person with a mental illness who has become demotivated about maintaining personal appearances and hygiene needs, the nurse needs to be highly sensitive to the client’s personal wishes while still encouraging normal hygiene behaviour. Adults whose health status is compromised by acute or chronic illness need specific support within a continuum from total self-care to being totally dependent for hygiene care. The dignity and privacy of all clients, especially the elderly, needs to be facilitated and protected whatever the context of hygiene care delivery.

The content of this chapter outlines both the scientific and practice based knowledge needed to promote and deliver hygiene care.

OVERVIEW

Subject knowledge

Knowledge from the physical sciences is explored in relation to the skin, mouth, eyes, hair, nails and perineum. In each section the focus is on the applied knowledge needed to make decisions about hygiene care. The psychosocial knowledge base integrates these specific body parts in order to outline issues in hygiene care related to development and individuality. Historical and social dimensions of hygiene care and cultural and spiritual norms are explored.

Care delivery knowledge

This part follows a format similar to the Subject Knowledge section, but concentrates on the knowledge needed in the assessment and delivery of hygiene care to and with patients and clients.

Professional and ethical knowledge

The professional, ethical, political and social dimensions of hygiene care are addressed. Privacy and dignity issues are explored. Hygiene care as a ritual within nursing is discussed with a particular focus on the role of the nurse as the key decision maker in this area of healthcare practice.

Personal and reflective knowledge

There is a particular focus on the reflective experiences of students in the delivery of care that is intimate and private (Evolve 14.5). Case studies are used to help consolidate knowledge gained from practice and the chapter content.

On page 333 there are four case studies, each one relating to one of the branch programmes. You may find it helpful to read one of them before you start the chapter and use it as a focus for your reflections while reading.

SUBJECT KNOWLEDGE

BIOLOGICAL

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE SKIN, HAIR, NAILS, PERINEUM, MOUTH AND EYES AS THEY RELATE TO HYGIENE CARE

The skin

The structure and functions of the skin are more fully outlined in Chapter 15, ‘Skin integrity’. Reference will be made here to some of the specific structures that are pertinent to skin and body hygiene. A key function of the skin is protection. Its unique structures protect the body from:

• undue entry or loss of water

• pressure and friction

• microorganisms

• chemicals (weak acids and alkalis)

• most gases

• physical trauma (alpha rays, beta rays to a limited extent, and ultraviolet radiation) (Montague et al 2005).

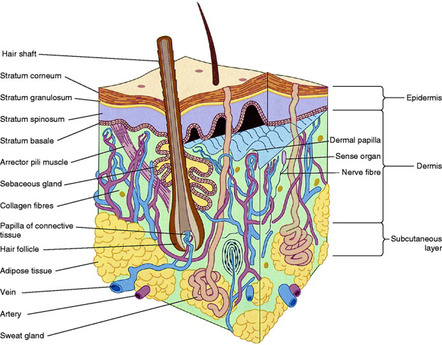

The two layers of the skin (Fig. 14.1), the epidermis and dermis, function as a single layer. However, the outer layer, the epidermis, has five layers of cell types, each of which has its own unique function. The innermost cell layer of the epidermis (the stratum basale) is important in skin regeneration as the cells are constantly dividing and reproducing, the life cycle of skin cells being approximately 35 days (see Ch. 15). These new cells move through the epidermal layers to the surface of the skin. For the purposes of hygiene care, the stratum corneum, the outermost horny cell layer, is therefore of primary interest. The cells or squames of the stratum corneum are all dead and are constantly being shed from the surface of the body. According to Montague et al (2005), up to 1 million of these cells are shed every 40 minutes through the process of desquamation or exfoliation.

|

| Figure 14.1 (from Montague et al 2005, with kind permission of Elsevier). |

Keratin helps the epidermis form a tough protective barrier. The process of keratinization, which begins in the basal layer, means that the horny cells of the stratum corneum are filled with this protein. Keratin is most evident in areas of the skin exposed to stress, for example the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Both psoriasis (a skin condition characterized by rapid and excessive production of keratin cells) and dandruff (hyperplasia of the scalp) result in the exfoliation of flakes of keratin (Montague et al 2005).

Certain bacteria are normally present on the skin’s outer surface, for example Staphylococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium. They are classified as normal flora (commensals) and are protective in function because they inhibit the multiplication of disease-causing organisms. These normal commensals, which inhabit the deeper layers of the stratum corneum, are not usually shed in exfoliation. Commensals use healthy skin scales as a source of food and also rely on the skin having a slightly acid pH in order to maintain their protective function in preventing disease (Montague et al 2005).

The dermis layer of the skin contains collagen and elastic fibres, nerve fibres, blood vessels, sweat glands, sebaceous glands and hair follicles. The last three are particularly significant in relation to hygiene care.

Given that commensals are a normal feature of human skin investigate the following:

• What are the ingredients of soaps ?

• How might the use of soaps affect the skin and the activity of skin commensals?

• How will babies, born with no resident skin commensals, gain these normal commensals?

• What effect might alcoholic skin preparations extensively used in alcohol hand rubs and also in cosmetic skin cleansers have on the skin commensals?

(See Evolve 14.1.)

• Describe the effects of soap on the skin.

• Explain the role of skin and its commensals as a protector against infection.

• Outline how hygiene care contributes to infection control.

Sweat glands

Eccrine (found throughout the body) and apocrine glands (responsible for odour and found at specific sites such as the pubis, genitalia, axillae) are two types of sweat (sudoriferous) glands; they are distributed throughout the skin and assist in temperature control. They produce sweat when the skin temperature rises above 35°C. Approximately 500 mL of sweat is produced each day in temperate climates. Secretion of sweat also occurs in response to stress and anxiety as well as to certain spicy foods. Both the production of sweat and its evaporation from the skin assist in heat loss from the body, and the rate of evaporation is particularly important in the patient with pyrexia (raised body temperature) (see Ch. 7, ‘Homeostasis’).

Sweat left on the skin, especially if from the apocrine glands of the axilla and genital areas, is responsible for body odour through the process of bacterial decomposition. The apocrine glands are dormant during childhood, but begin actively to secrete sweat during puberty and continue to do so throughout adult life. The widespread use of deodorants in developed countries is based on the principle that these solutions will kill the bacteria and mask any odour produced. Antiperspirant sprays block the openings of the ducts to the sweat glands with metal salts such as aluminium (Montague et al 2005).

Sebaceous glands

Sebaceous glands secrete sebum into the hair follicles. This sebum is an oily odourless fluid, containing cholesterol, triglycerides, waxes and paraffins, that lubricates the skin and keeps it supple and pliant. Sebum also has a role in waterproofing the skin and is inhibitory to many microorganisms. Sebaceous glands are found in highest numbers over the scalp and face, the middle of the back, the genitalia and in the auditory canal.

Babies and young children have relatively fewer and less active sebaceous glands and are therefore more prone to skin redness and excoriation in damp conditions, while the loss of sebaceous glands in old age also makes the skin of the elderly more vulnerable to damp conditions, redness and to breakdown. During the menarche (puberty in females), however, the secretion from sebaceous glands increases in response to an increase in adrenocortical hormones. The increasing output of sebum during the teenage years combined with hereditary factors can contribute to the development of acne vulgaris (common acne) (Hockenberry & Wilson 2007).

Hair

The hair follicle is situated in the dermis and is surrounded by its own nerve and blood supply. Sebaceous glands and sweat gland ducts open directly into the hair follicle causing the scalp to become moist and oily, particularly in a hot environment. The cycle of hair growth comprises a period of growth for up to 2 years followed by a rest period and then atrophy. About 70–100 scalp hairs are normally lost each day.

Certain factors affect the rate of normal hair growth and loss. These include:

• nutrition (hair loss in low calorie diets and starvation)

• hormones (puberty with increase in body hair)

• hereditary factors (baldness)

• age (decreased number of hairs with old age).

Most of the body is covered by hair, but it varies in type. Lanugo is the fine silky hair found on the fetus in utero and on premature babies, and which is lost from the body soon after birth. Vellus is colourless hair found on the female face. Terminal hair is found on the adult head and pubis and is the subject of hygiene care in relation to maintaining healthy hair covered later in this chapter.

Nails

Nails are keratinized plates resting on the highly vascular and sensitive nail bed. The external appearance of the nail bed is often used to indicate general health status as the shape, colour and condition of fingernails are easily observed. Toenails cause more problems for individuals than fingernails. Debilitated adults may have difficulties in maintaining adequate care and hygiene for their feet which will lead to their toenails becoming thick, brittle and prone to fungal infections. Children may have problems with ingrowing toenails because of difficulties in maintaining well-fitting shoes, especially in times of rapid growth such as during adolescence.

The perineum

The perineum is the area located between the thighs, extending from the anus (posterior) through to the top of the pubic bone (anterior). Anatomical structures in this area are concerned with the expression of sexuality, reproduction and elimination (see Ch. 16, ‘Sexuality’, and Ch. 18, ‘Continence’).

In the female, the external genitalia (vulva) consists of the mons pubis, clitoris, urethral and vaginal orifices, and the labia majora and minora. The normal moist environment around the vaginal orifice is maintained by secretions from Bartholin’s glands, which are mucus-secreting glands in the lateral wall of the vagina. The slightly acid secretion varies in amount during the ovulation cycle, has a slight odour and helps to inhibit bacterial growth.

In the male, the perineal area includes the penis, the scrotum and the anus. The end of the penis (glans penis) through which the urethra opens in the centre is covered with a skin flap or foreskin in the uncircumcised male. Because the skin of both the penis and the scrotum is thin and hairless it is more easily irritated and injured than skin elsewhere.

The perineal areas of both men and women are prone to infections because they contain openings into the body and are also warm and moist environments. In both sexes, the urethral orifices lead to sterile bladders, but are in close proximity to the anus, which opens into the ‘unclean’ rectum. The main aim for hygiene care in this area is to prevent or eliminate infection. Prevention of odour is closely linked to the prevention of infection and is a cultural preoccupation in developed countries.

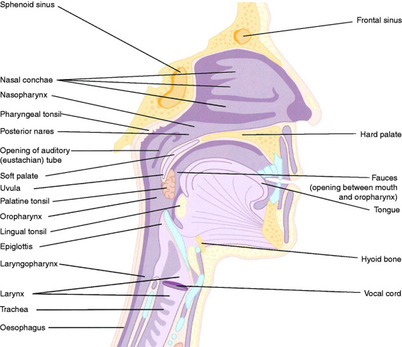

The mouth and teeth

The mouth has many physical and psychosocial functions that are important in supporting the health and well-being of an individual (Box 14.1). The mouth or oral cavity forms the first part of the gastrointestinal tract (Fig. 14.2). It is lined by mucous membrane, which along with the three pairs of salivary glands – the parotid, sublingual and submandibular – secretes mucus and saliva to aid the mastication and digestion of food. The tongue is a large muscular organ involved in taste, speech and swallowing. There are numerous papillae and taste buds on the upper surface of the tongue. The teeth masticate food, help to shape the mouth and are involved in the formation of speech sounds. The deciduous teeth begin to erupt at between 5 and 8 months of age. In childhood there are normally 20 deciduous teeth. Gradual exfoliation of the deciduous teeth begins approximately from the age of 6. These teeth are replaced by 32 permanent teeth by the age of 18–25 years. A full complement of teeth has 16 in the lower and 16 in the upper jaw. Knowledge of the natural loss of teeth in childhood is important to the nurse caring for a child going for surgery under a general anaesthetic, as loose teeth may fall out and be inhaled during induction of anaesthesia.

Box 14.1

• Ingestion and mastication of food

• Digestion of food

• Taste

• Formation of speech

• Social interaction – non-verbal expressions

• Psychosexual – expression of body image and intimacy

|

| Figure 14.2 (from Montague et al 2005, with kind permission of Elsevier). |

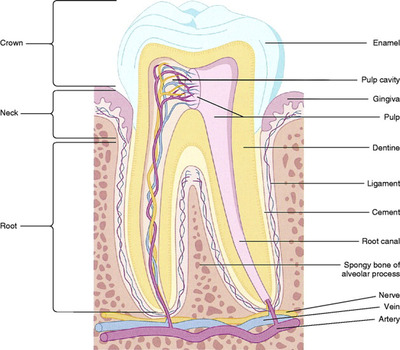

The structure of the adult tooth contains three parts: the exposed section of the tooth is the crown (enamel), the root (dentine) which is held in place in the jaw bone by cementum, and the pulp cavity, which contains the blood vessels and nerves (Fig. 14.3).

|

| Figure 14.3 (from Montague et al 2005, with kind permission of Elsevier). |

Dental hygiene

The two major types of oral problems in the normally healthy individual are periodontal disease and dental caries (cavities). Dental caries involve the calcified structures of the tooth. Bacterial enzymes combined with dental plaque produce organic acids, which decalcify both enamel and dentine. Cavities or caries begin to develop once the bacteria have access to the central matrix of the tooth.

Gingivitis is a reversible prevalent disease of the gingivae (gums) and in some cases can lead on to periodontal disease. Clinical features of gingivitis include red, swollen, bleeding gums. Periodontal disease is a chronic irreversible disease of the gingivae and supporting tissues of the tooth, i.e. the cementum, periodontal ligaments and underlying jawbone. Clinical features of periodontal disease (periodontitis) include chronic and/or acute gingivitis, gingival recession, leading to the root (dentine) becoming exposed in the oral cavity, severe bone loss, tooth mobility and ultimately premature tooth loss.

Saliva plays an essential role in maintaining a healthy mouth. Thin watery saliva flushes away some debris from around the gums and teeth and buffers any acids in the mouth. Thick sticky saliva will aid the formation of plaque and therefore increases the risk of periodontal disease and dental caries (Griffiths & Boyle 2005).

Halitosis (‘bad breath’), also known as oral malodour or foetor oris, is a common complaint and has many causative factors which include strong spicy foods, coffee, smoking, alcohol, certain drugs and xerostomia (dry mouth). However, dental plaque is also a primary factor of halitosis due to its metabolic activity. Poor oral hygiene activity can lead to halitosis. People who stop cleaning their mouths will soon develop halitosis. Any form of oral sepsis such as gingivitis or periodontitis will produce a degree of halitosis. Rarer causes include diabetic ketoacidosis and severe renal or hepatic problems (Griffiths & Boyle 2005).

The prevention of peridontal disease and dental caries is necessary to control premature tooth loss throughout the lifespan. Particularly vulnerable times for tooth loss are during childhood and teenage years and the third age (over 50 years old). Pregnant women have a higher susceptibility to gum disease (pregnancy gingivitis) due to the increase of hormonal activity which exaggerates the way the gum tissues react to the bacteria in plaque. This results in an increased vulnerability to gum disease if there is not good control of plaque formation. It is important to note that it is the plaque and not the increased hormone levels that is the major cause of pregnancy gingivitis.

Health promotion strategies addressed to all ages must take into account the interaction between the oral environment of the individual and dental plaque. As soon as food and drink are ingested, the acidity in the mouth increases. The pH is lowered considerably by foods containing sugar and until the acidity is buffered by saliva there is a risk of demineralization of the teeth with subsequent decay. The mouth contains many varieties of bacteria, which do not cause problems if suspended in saliva. However, once these organisms attach themselves to the teeth, gums or tongue surfaces via a mucopolysaccharide glue they become insoluble in water and problems begin. The bacterial deposits cannot be rinsed away and dental plaque forms. Plaque takes 24 hours to develop. It causes periodontal disease and dental caries, which may eventually lead to systemic disease.

You are undertaking a practice placement with the primary healthcare team and have had experiences working alongside the health visitor, the practice nurse and a school nurse. Reflect on the health promotion advice given by each of these three nurses in their particular roles and with their particular client groups.

• Note the questions asked by clients related to those areas that deal with all aspects of hygiene care to include skin care, oral and dental care and hair care.

• Note the specific advice given by these health professionals and how it relates to your current knowledge base.

• What health promotion strategies were being used to encourage compliance with advice given?

• Record your learning in your portfolio.

The eyes

The eye is a delicate organ with its own built-in mechanisms for protection and hygiene. The conjunctiva covers the exposed surface of the eye and the inner surface of the eyelids and helps to prevent drying of the eye. The eye produces tear fluid, which is washed across the eye by the regular blinking action of the eyelashes. Tear fluid contains salt, protein, oil from sebaceous glands and a bactericidal enzyme called lysozyme, which helps protect the eye against infection. Tears are produced by the lacrimal and accessory glands, which respond to reflexes and the autonomic nervous system. Tears need a drainage system if the eye is not to become ‘watery’ (epiphora). Drainage is normally via canaliculi at the inner end of the lid margin into the lacrimal sac and duct and finally into the nasal cavity. Any condition that interferes with these three protective mechanisms may cause problems:

• People who wear contact lenses, particularly in a dry centrally heated building for long periods, may be at risk of excessive drying of the cornea and subsequent inflammation (Montague et al 2005).

• The person who has had a stroke or is unconscious for any reason may be vulnerable to eye infections without adequate eye hygiene.

• Many elderly people suffer from ‘watery eye’ and may require surgery to prevent secondary infections (Montague et al 2005).

• Neonates and young children are prone to get what is known as ‘sticky eyes’, and the condition may be due to blockage or malformation of the lacrimal ducts and require surgery.

• Chlamydia infection passed from the mother to the baby during childbirth can cause serious eye infection in the neonate.

• Bacterial conjunctivitis can be a common problem in children’s nurseries and schools, especially as children are prone to rub their eyes with dirty hands (Hockenberry & Wilson 2007).

PSYCHOSOCIAL

INDIVIDUAL ASPECTS OF HYGIENE CARE

Beliefs and attitudes to personal hygiene are developed during childhood and are strongly influenced by social and cultural norms. Nurses, aware of the scientific principles on which they base their beliefs about hygiene care, need to be sensitive to the family and cultural influences on their clients.

Historically, hygiene practices have been influenced by:

• social norms

• religious rituals

• the environment (accessibility of water for bathing)

• evolution of hygiene aids (e.g. showers, soaps, razors, electric toothbrushes, hair dryers).

Hygiene maintenance is a normal daily occupation and promotes a feeling of security and stability alongside well-being and self-esteem. An important stage in the development of independence in hygiene self-care in childhood occurs during the toddler and preschool phase (i.e. at 1–6 years of age). During this time children develop physically, learn to gain self-control and mastery over body functions, and become increasingly aware of their own dependence and independence (Hockenberry & Wilson 2007). The social and cultural beliefs of the family are of great importance in this preschool period in influencing attitudes and practices in hygiene care, and health promotion is usually directed through the parents/carers of the child. Peer influences become increasingly important through the school years and hygiene habits for both sexes may be influenced more by advertising, peer support and the wish to conform to group and sexual norms. Health promotion strategies by healthcare professionals during this phase of development need to consider these predominant social influences. During the late teenage years, values and attitudes become internalized and each individual justifies for themselves their choices in hygiene care. For adults, the influence of advertising which directs its message of responsibility to the family unit, particularly the mother, has an effect on patterns of hygiene practice in society (Aiello & Larson 2001). Anxiety in an individual can lead to an obsession with hygiene care expressed through frequent hand-washing and cleaning. Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) is relatively common within the general population and specialist help is needed to deal with the problem.

CULTURAL AND SPIRITUAL ASPECTS OF HYGIENE

Historically, bathing was an important social activity and public baths were a feature of ancient Greek, Egyptian and Roman society. The ancient Roman facilities included exercise rooms, hot, warm and cold baths, steam rooms and dressing rooms. These facilities are again very evident in Western societies with the growth in numbers of modern health and fitness centres which include saunas, steam rooms and jacuzzis. Sociologists have argued that this recent trend is linked with treating ‘the body’ as a consumer commodity that must be maintained and groomed to achieve maximum market value (Lupton, 2003 and Twigg, 2006). Body maintenance in the interest of good health is linked with the desire to appear sexually attractive in both sexes, but more especially for women. However, cultural habits in hygiene care still demonstrate links with past beliefs, which are often expressed culturally (Helman 2007).

The early Christian church considered physical cleanliness as less important than spiritual purity and after the decline of moral standards in the Roman Empire discouraged public bathing. Bathing, even in private, came to be regarded as unhealthy and was considered an indulgence. In the Middle Ages, the use of water to clean the body was rare and the only areas that needed to be cleansed were those visible to others. Even then, the ‘dry wash’, which involved rubbing one’s face and hands with a cloth, was considered healthy right up to the 17th century. The use of hot water was considered unhealthy as people believed that the pores of the skin would open and allow infection to penetrate the body, therefore being covered up meant that the body was protected from disease. Lay beliefs about how we become susceptible to colds can echo these earlier beliefs, e.g. ‘allowing one’s head to get wet’, ‘going outside after washing one’s hair’, ‘getting one’s feet wet’, ‘getting caught in the rain’ (Helman 2007).

The relationship between bathing, body hygiene and becoming healthy changed with the Industrial Revolution when the body could then be compared with a machine; the use of cold water was seen as invigorating and helping to firm up the body and also became associated with moral austerity. With the scientific discovery of microbes, washing became important to rid the body of disease, touching of certain body parts considered ‘dirty’ became prohibited and more frequent washing was encouraged. At this time, buildings did not include bathing facilities and it was not until the level of dirt and disease increased after the Industrial Revolution that demand increased for good bathing facilities to reduce cross-infections such as cholera. By the late 19th century, private homes of the upper classes began to have separate rooms set aside for bathing, and municipal baths were built for the general public to use.

In developed countries today most private homes have their own bathroom facilities, which are often multiple as en suite bathrooms have become the norm in new housing at the end of the 20th century. There is now a more marked preoccupation with cleanliness and showers have become more commonplace, even in temperate climates.

Bathing has also been an integral part of the ritual cleansing of religious practices over many centuries. Baptism in Christianity and the mikvah in Orthodox Judaism are derived from bathing rituals, while bathing is an important part of Muslim and Hindu religious ceremonies. Muslims perform ablutions before prayer and are very particular that all bodily excretions are removed.

Culturally certain hygiene habits may appear distasteful and noisy to nurses in developed countries. Internal cleansing rituals such as sniffing water up into the nose and blowing it out into a basin may provoke disgust, but this can be a normal practice among Muslims and Hindus, while colonic irrigations are a method of internal cleansing of the gut among those who practise yoga.

The ‘short back and sides’ image of hair hygiene in developed countries is not relevant to a Sikh, to whom the hair (kes) is sacred and should not be cut, but should instead be kept covered by a turban. Rastafarians do not like to wash their long hair.

Items of clothing are also sacred in certain cultures and should not be removed during hygiene care. These can include neck threads (marriage thread for Hindu women), bangles and comb (kara and kasngha for Sikhs), nose jewels (wedding symbols for Bangladeshi women), and a stone or medallion around the neck (protection for Muslims). There are many other cultural and religious habits among different cultural and religious groups that have an important impact on the delivery of appropriate and sensitive hygiene care. It is important to be sensitive to any requests that may seem strange, but are in fact normal to the individual concerned (Hollins 2006). Knowledge and sensitivity to religious practices after death, when body care needs to be delivered according to certain rituals, is essential for the delivery of holistic care.

Review your own personal hygiene routines and practices over 1 week. Reflect on what or who have had the most influence on your current practices. What standard of hygiene care would you find intolerable for yourself? (Recall situations when you did not have access to hygiene facilities for whatever reason.)

In your practice placement in a healthcare institution:

• Review the quality of hygiene facilities and also access to them.

• Observe whether there are institutional patterns in the delivery of hygiene care.

• Analyse to what extent current facilities and patterns of care allow for the particular cultural and spiritual norms of the individuals who are experiencing health care.

• Record your findings in your portfolio.

ASSESSMENT OF AN INDIVIDUAL’S HYGIENE NEEDS

Decision making around the delivery of hygiene care to a patient or client is dependent upon many factors, which include the patient’s ability to self-care, the facilities available, including family members or informal carers, and the nurse’s expertise and time. Accurate assessment of the individual patient’s needs and level of participation should be encouraged wherever possible. Although there is still a need for the timing to be negotiated to fit organizational needs, the ritualization of bed bathing to the morning shift, whether in hospital, hostel or community, should be a thing of the past.

With children, infants and babies, bath times and routines in any healthcare facility should mimic as closely as possible the child’s normal routine with the parents or significant carer being involved directly in providing care. Although the child may view hygiene rituals as unpleasant, they can be fun. There should be facilities both in time and the design of the environment that will maintain and encourage playtime for the infant and young child during the delivery of hygiene care. Children also need privacy, but there should be a balance between allowing them privacy and understanding how much help they require to be safe and to achieve the goals of good hygiene. A baby needs a warm environment and less exposure to prevent chilling. Teenagers will expect that facilities will allow them to maintain their privacy, while older adults may expect the nurse to respect their usual routines for bathing and not demand bathing as a daily ritual if their normal habit is to bath less frequently (Zeitz & McCutcheon 2005).

The ability to care for one’s own hygiene needs is important to all individuals and is a prime motivating factor in focusing the nurse on teaching self-care to children or adults with intellectual disabilities. Goals set should be commensurate with the individual’s intellectual ability and may need to be frequently revised in order to allow feelings of achievement if progress is slow. Being sensitive to the intimate nature of care and the need for personal control is important in facilitating privacy and dignity. Perceptions of lack of control can lead to the client being agitated and aggressive (Carnaby & Cambridge 2006).

Sheppard (2006) reports on the evaluation of a personal development programme entitled ‘Growing Pains’ for 11–15-year-old students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in a specialist school in Australia. Following a 20 week development programme for 68 adolescents, data revealed positive trends in individual personal development in most topic areas. However, one sub-topic, ‘personal hygiene’, showed almost no change across the group. The author recommended that future studies on this client group should investigate more effective means of teaching personal hygiene skills.

The motivation to maintain personal hygiene as part of a personal self-image can be lost when a person is depressed or disturbed mentally. The nursing role is then focused on encouraging self-care through specific behaviour modification techniques or other counselling approaches that aim to improve the individual’s feeling of self-esteem. Equally, the individual may be confused or have a loss of short-term memory and need constant direction in order to be encouraged to maintain his or her independence in hygiene care (Roe et al 2001).

During your practice placement you are allocated on a morning shift to work with a registered nurse (RN) who has responsibility for the care of six elderly women with varying degrees of mental and physical disabilities. The RN is keen that all hygiene care should be delivered by the end of the morning.

• Decide on what information you need to collect in order for you to make decisions on how to prioritize the care you give.

• Reflect on and discuss how you would cope with the wishes of the RN to complete the care by lunchtime.

(In completing this exercise, cross-reference to any work you have done on assertiveness and dealing with potential conflicts of opinion.)

ASSESSMENT FOR BODY HYGIENE CARE

The activity of washing removes sweat, sebum, dried skin scales, dust and microorganisms from the skin’s surface. If not removed, microorganisms multiply and lead to body odour and infection. When people are ill, increased anxiety can lead to increased sweating and therefore the need to wash more frequently. In surgical patients, a preoperative shower or bath is essential; prevention of wound infection and cross-infection is a paramount consideration in decisions about how often and by what method to deliver hygiene care postoperatively. Patients who are incontinent will need more frequent and sensitive attention to their hygiene needs.

Aesthetically care should be given according to the norms of good taste and culturally specific values. The method selected should be effective in terms of the patient’s and the nurse’s time and energy. It should promote and maintain the patient’s independence, enhance the nurse–patient relationship and provide an opportunity for two-way information processes such as health promotion activities. Body hygiene care may also be therapeutic if part of a treatment regimen that includes the need for exercise of joints and muscle relaxation while the individual is submersed in warm water. Perineal hygiene care post childbirth also promotes wound healing in the mother who has perineal sutures (Spiby et al 2005).

Decision making around hygiene care is concerned with skilful adaptation of practice when the facilities within the context of care and the actual needs of the patient are incongruent.

Facilitating body hygiene care

There are many different ways of delivering body hygiene care (Box 14.2 and Evolve 14.2). Although nurses in multiple contexts use some or all of these methods on a daily basis, textbooks generally concentrate on the techniques of bed bathing the highly dependent patient (Nicol et al 2008). There has been a major shift in conventions around decision making in this area of total body hygiene as the emphasis is placed on patient independence in maintaining his or her own hygiene care.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree