4.1 Introduction

In this chapter we provide an opportunity for you to think consciously and deliberately about your clinical experiences and to reflect on them in ways that are meaningful, beneficial and action orientated. We show you how to consider your thoughts and feelings carefully, in preparation for, during and after your placements. You will also have opportunities to evaluate your strengths and limitations, to consider feedback provided by others and to develop strategies for improvement. In this chapter we emphasise that the journey of lifelong learning is the responsibility of every nurse and that learning depends upon your ability to be a reflective practitioner. Lastly we challenge you to develop your emotional intelligence, to become a critical thinker and to engage thoughtfully in the clinical reasoning process.

4.2 Caring

Nurses enter the nursing profession because they care about people and society. However, nurses do not have the monopoly on caring. Parents care for their children, teachers care about their students, doctors provide clinical care for their patients and chaplains provide pastoral care. So why do professionals view caring differently? Caring is one of those concepts that can be elusive and have different meanings. The literature provides many examples, definitions and theories of caring (Bourgeois & Vander Riet 2009; Brinkman 2008; Crisp & Taylor 2009; Persky et al. 2008; Warelow et al. 2008). For some, caring and nursing may seem to be the same, but others will differentiate caring from nursing.

Nurses understand caring from many perspectives that reflect their experiences, context of practice and knowledge. One way to understand caring is to view it as discourses of caring. Discourses are groups of statements that act to constrain and enable what we know (Bourgeois 2006, 2008). A finite number of statements contribute to a discourse and these recur time and again, so that we come to see certain statements (often made by very prominent people) as truths. Take, for example, the statement, ‘Caring is nursing’. This often-repeated statement in the literature is perceived differently by individual nurses.

Three discourses of caring are evident in nursing (Bourgeois 2006)—that is, nurses speak about caring from a position within different discourses, using words and statements that define and inform others about caring. These discourses are ‘caring as being’, ‘caring as doing’ and ‘caring as knowing’. Nurses who speak about caring will use statements that belong to these different discourses.

In the discourse ‘caring as being’, nurses speak about caring as an element that is intrinsic and essential for nurses. Caring for these nurses is part of their nature as human beings, involving them in caring relationships. You may hear some of your peers claim, I was born to be a nurse. It is in my family; all my family are nurses’, ‘Caring is a part of me’ or ‘All I want to do is care for others’.

The discourse ‘caring as doing’ is evident when nurses talk about caring as actions and behaviours. They may mention skills and procedures as proof of their caring actions for patients. Nurses speaking from within this discourse refer to caring using complex concepts, such as providing comfort, showing compassion and helping others.

‘Caring as knowing’ is a discourse that contributes ideas and practices associated with the knowledge base essential for nursing. Nurses use statements in which they claim to own caring. Caring theorists have contributed much to this discourse (Leininger 1991; Orem 1991; Euswas 1993; Watson 1999; Watson et al. 2002).

Consider the following questions:

![]() Coaching Tips

Coaching Tips

• Reflect on the meaning of caring and identify what it means to you. Try to define caring using words and statements that have meaning for you. Consider how you demonstrate caring in your practice. Seek feedback about your practice from patients, peers and mentors. Does this feedback support your definitions and ideas about what caring is?

• Think about practices that may affect your placement and your ability to undertake care: for example, the mix of staff on the ward or the model of care implemented.

• Consider your personality, philosophy and beliefs. How do these affect your caring practices?

• Reflect upon the different types of placements that you undertake throughout your program. Do you care differently for patients in different practice contexts? Compare, for example, caring for people in a perioperative, emergency room or aged care placement.

4.3 Reflective practice

Something to think about

Something to think about

The unexamined life is not worth living

Socrates

At the risk of stating the obvious, simply undertaking a clinical placement does not necessarily develop competence—just being there does not guarantee learning. Developing competence involves not only taking action in practice, but also learning from practice through reflection. Reflection is intrinsic to learning. It allows nurses to process their experience and explore their understanding of what they are doing, why they are doing it and what impact it has on themselves and others (Boud 1999).

The skill of reflection is pivotal to the development of your clinical knowledge and understanding. Reflection allows you to consider your personal and professional skills and to identify the need for ongoing development. As a nursing student you should become increasingly aware of your professional values, skills, strengths and areas that require further development.

While we can and do learn from a wide range of experiences (good and bad), learning is often initiated by painful, difficult, embarrassing or uncomfortable experiences. Don’t just try to forget about these challenging times. Reflection is about exploration, questioning, learning and growing through, and as a consequence of, these experiences.

Devoting some time to reflection during and after each clinical placement allows you to plan for future clinical experiences and to develop clear and appropriate objectives for your next placement. At the very least, reflecting on your experience provides information that you can take to clinical or academic staff for help or guidance in further professional development.

4.3.1 Keeping a journal

The process of reflection provides the raw data of experiences. In order to use these experiences creatively, to transform them into knowledge, the additional stage of writing is required. Writing fixes thoughts on paper. As you stare at what you have written, your objectified thinking stares back at you. As you rearrange your writings, you often find that you are loosening your imagination by combining various ideas and thoughts. Creative ideas occur during the mechanical process of giving them shape (van Manen 1990). Reflections are the raw materials, but they are turned into knowledge as you write—sometimes you don’t know how much you know until you write it down.

Many nursing programs require students to participate in some form of formal written reflection. Students often have to submit a paper-based or online journal that describes their reflections about their clinical experience, including application of relevant theory, and their understanding of their experience. Even if this is not a formal requirement at your educational institution, it is certainly wise to keep a personal journal as the reflective writing process allows you to clarify your values, affirm your strengths and identify your learning needs.

Discerning and describing the knowledge, competence and skills that go into day-to-day nursing work allows nurses to understand their work in a more empowering way. This increases nurses’ mastery and appreciation of their own work and their ability to care better for patients (Buresh & Gordon 2000).

Something to think about

Something to think about

Observation tells us the fact, reflection the meaning of the fact.

Florence Nightingale (in Baly 1991)

![]() Coaching Tips

Coaching Tips

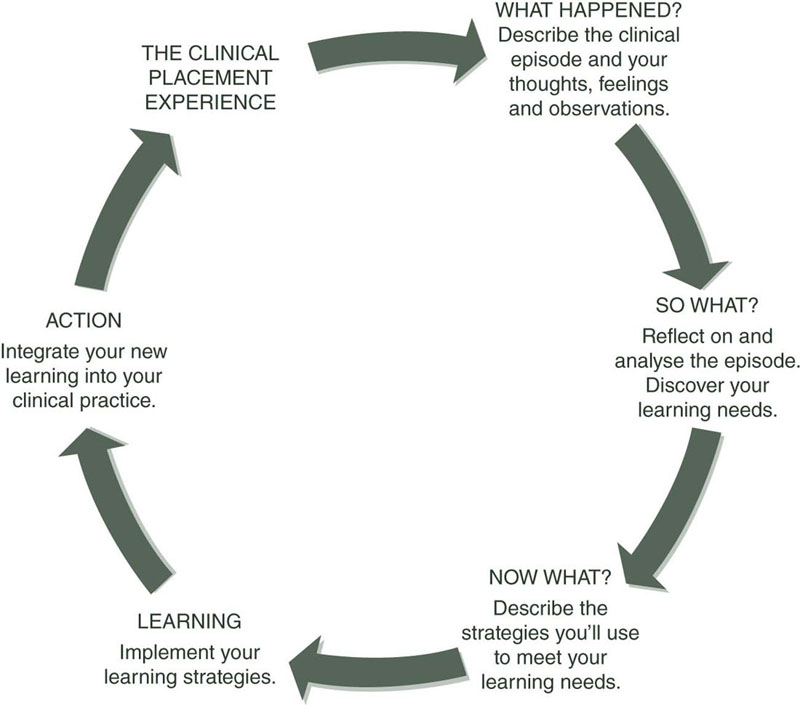

There are many resources to help you develop your ability to become a reflective practitioner, and your lecturers may recommend a process. Figure 4.1is a diagrammatic representation of one method of reflection that many students find clear and easy to follow. Give it a try—you may be surprised how insightful you become! Then read Mr Jackson’s story.

Mr Jackson’s story is an example of reflective journal writing and the application of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (ANMC) competency standards (ANMC 2006). Behaviours that reflect an element of the ANMC competencies are followed by the relevant competency in square brackets.

I was looking after Mr Jackson (pseudonym), a 76-year-old man, who was 2 days post-op following a right hip replacement. As I entered Mr Jackson’s room to take his 10 a.m. observations I noticed that he was restless [5.2 Uses a range of assessment techniques to collect relevant and accurate data]and when I spoke to him he did not seem to comprehend my questions, replying inappropriately. I did not recall his confusion being reported at handover. I introduced myself to Mr Jackson and his wife [9.1 Establishes therapeutic relationships that are goal directed]and asked whether Mr Jackson had been confused before his hospital admission [5.2 Uses a range of assessment techniques to collect relevant and accurate data]. His wife replied that she had never seen him like this before.

I reassured her and explained [9.2 Communicates effectively with individuals/groups to facilitate provision of care]that I would take his observations and then consult the RN [Registered Nurse]I was working with [7.3 Prioritises workload based on the individual’s/group’s needs, acuity and optimal time for intervention]. I realised that this situation was beyond my scope of practice [2.5 Understands and practises within own scope of practice].

I started to consider some of the possible causes for Mr Jackson’s confusion. I wondered whether he was in pain but he did not reply when I asked about his pain. I thought that he might have been hypoxic, and when I took his SaO2 it was 88 per cent and his respiratory rate 28. His BP [blood pressure]was elevated compared to his pre-op BP; his pulse was rapid, full and bounding. He was afebrile. I checked that his IV [intravenous]was running and his catheter draining. I also checked the wound dressing, which was dry and intact [5.2 Uses a range of assessment techniques to collect relevant and accurate data; 7.1 Effectively manages the nursing care of individual/groups].

I then documented my observations [1.1 Complies with relevant legislation and common law]. I reassured Mr Jackson and his wife that I would consult with the RN and return [9.2 Communicates effectively with individual/groups to facilitate provision of care]. I put the bed rails up [9.5 Facilitates a physical, psychosocial, cultural and spiritual environment that promotes individual/group safety and security]before I left the room, as I was concerned for Mr Jackson’s safety. I discussed my observations and concerns with the RN [2.5 Understands and practises within own scope of practice; 10.2 Communicates nursing assessment and decisions to the interdisciplinary healthcare team and other relevant service providers]who immediately returned with me to review Mr Jackson.

The RN asked Mr Jackson to point to anywhere it hurt and he touched his head. She checked the IV rate and found that it was running at 125 mL/h. When the RN compared the rate to the fluid orders chart, she found it was meant to be running at 84 mL/h. She calculated that the catheter had drained less than 40 mL in 4 hours. The RN asked Mr Jackson’s wife if he was normally so puffy around his eyes and she replied that he wasn’t. She listened to his chest with a stethoscope and rechecked his SaO2, this time with an ear probe as his hands were cold, which could give inaccurate results. The RN explained to Mr Jackson and his wife what she was doing and said that she would phone the doctor immediately.

Outside the room the RN explained to me that she suspected hypervolaemia, renal impairment and possibly electrolyte imbalance and that she was concerned that Mr Jackson would develop pulmonary oedema if he were not treated quickly. She thanked me for bringing Mr Jackson’s cognitive impairment and abnormal observations to her attention. Review by the doctor and follow-up pathology tests later confirmed the RN’s preliminary nursing diagnosis.

I feel that I undertook a good but very general assessment of Mr Jackson. However, I realised after watching the RN that I need to develop more focused and comprehensive assessment skills [4.4 Uses appropriate strategies to manage own responses to the professional work environment]. I also believe that a deeper knowledge base would allow me to analyse and interpret abnormal observations more accurately. In particular, I need an understanding of the potential causes of confusion in elderly patients, and skills and knowledge related to fluid status assessment so that I can provide a better standard of care to my patients [3.1 Identifies the relevance of research to improving individual/group health outcomes]. It was inspiring to observe a RN who had the experience and knowledge to thoroughly and efficiently assess Mr Jackson and establish an accurate nursing diagnosis.

4.4 Reality check and seeking feedback

So far the focus in this book has been on the clinical environment and your place in it. Now it’s time to turn the focus completely onto you, by asking you to address the following questions:

This is not a once-only activity, but rather a lifelong process of personal and professional development. This ‘reality check’ is pivotal to your ongoing growth and improvement and is a process that you’ll find invaluable to your career success.

4.4.1 How do I see myself?

To answer this question you should begin by assessing and listing your skills and attributes (clinical, interpersonal and others) and identifying your strengths and limitations. Skills are acquired abilities. Attributes may be acquired or intrinsic. There are three main types of skills and attributes:

• technical or clinical skills, such as those involved in providing oral care to an unconscious patient or safely administering medications;

• interpersonal skills, which include communication, empathy and being supportive (among others);

• personal attributes, such as adaptability, motivation, resilience and problem-solving.

Take some time to reflect on your skills and consider areas in which you excel and those that require further development. Identifying gaps or limitations is just as important as acknowledging your strengths.

4.4.2 How do others see me?

Once you have completed your self-assessment, you should validate it by seeking feedback from others. You can obtain this feedback from managers, educators, clinicians and fellow students. Performance appraisals and informal feedback are invaluable to understanding how others perceive you. Asking for feedback is not always easy, but your success depends on your openness to different perspectives. It involves listening and accepting positive and negative feedback, and acknowledging the areas in which change and improvement are needed. Seeking advice about new skills that you require and strategies to develop them is also essential.

Now compare the skills and attributes that you identified with the feedback from others. Are there any discrepancies? Did others recognise skills and attributes that you were not aware of but can now build on? Were limitations identified that you were not aware of?

Something to think about

Something to think about

If life is to have meaning, the extent to which you know yourself is the most important work that you will ever do.

Crow (2000, p. 33)

![]() Coaching Tips

Coaching Tips

It is your right (and responsibility) as a student to seek ongoing and regular feedback about your performance. Most educational institutions have a formal process to ensure this occurs. However, you should still seek informal feedback regularly. Make time for regular performance conversations. Ask for specific concrete feedback about your skills, attributes, strengths and limitations and use the feedback as a springboard to success.

Lastly, receiving formal feedback should be a positive experience and should not display any hidden agendas, such as the discussion of any previously unmentioned problems. All problem areas should be dealt with when they occur and not stored up to be revealed only at a performance review. You deserve regular formative feedback throughout your placement and opportunities to improve.

Grievance procedures are available if disagreements are unable to be resolved between you and your assessor, and you should consult your educational policies for guidance. Conflict and confusion, if they arise, should be dealt with constructively and sensitively.

4.5 Emotional intelligence

To survive and succeed in nursing you need to develop not only technical skills and knowledge, but also emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence is the ability to identify and manage the emotions of one’s self and of others. Some argue that emotional intelligence is a determining factor in achieving competence and a more accurate predictor of success than intellectual ability (Goleman 1998). Emotional intelligence is a term that encompasses the human skills of self-awareness, self-control and adeptness in relationships, all of which are recognised as being central into effective nursing practice (Taylor 1994). Emotionally intelligent individuals excel in human relationships, show marked leadership skills and perform well at work (Goleman 1996). Emotional intelligence also includes persistence, ability to motivate oneself and altruism. At the root of altruism lies empathy, or the ability to read emotions in others, which forms the basis of therapeutic relationships (see Chapter 5). If empathy is limited or lacking, if there is no sense of another’s need or despair, then there is no care or compassion.

A wealth of literature supports the view that therapeutic relationships between nurses and patients are correlated with positive patient outcomes. As nursing is a ‘significant, therapeutic interpersonal process’ (Peplau 1952, p. 16) nursing students must develop competence in dealing with their own and others’ emotions. The emotional state of the patient/client is often heightened during illness and nurses should be equipped to respond with empathy and genuine concern. It is important to understand that people who are experiencing illness, stress, anger, pain, fear or frustration may react in different ways. Some will become quiet and withdrawn, others angry or aggressive. While the former seems easier to manage the nurse still requires skills in therapeutic engagement to provide support and care. By contrast, anger and verbal abuse from a patient or carer may adversely influence a nurses’ perception of a patient (Rothwell 1971, p. 241). While it is natural to want to protect oneself by emotionally withdrawing or angrily responding to a threatening or verbally abusive patient, it is necessary to overcome the emotional impact and still address the patient’s needs, conflicts and stressors (Jay & Clermont 1996). Consider the following example and how you might feel if confronted with the situation recounted by this nurse:

My patient had cancer and refused treatment. As she was found to be able to make that decision we were treating her palliatively. Her daughter said that I was an incompetent f***** who was unable to f***** do anything f***** right and would I go get some other stupid nurse who might at least want to keep patients alive. Then she said she was going to take her mother out of this f***** place.

![]() Coaching Tips

Coaching Tips

In dealing with these types of situations it is important to first understand one’s own emotional reaction. Then try to moderate your initial response and begin to understand the person’s emotional reaction and the reason for it. This may sound easy, but it isn’t. Nurses are only human and in most cases when they feel wounded by a patient’s verbal aggression or swearing, there is a strong sense of the hurt stemming from the discrepancy between the care the nurse perceives s/he has invested in the patient and the patient’s or carer’s lack of appreciation of that care (Stone 2009). However, the core of emotional intelligence is empathy—the capacity to understand another person’s subjective experience from within that person’s frame of reference (Bellet & Maloney 1991). It includes the inclination to invest therapeutic effort by putting into action appropriate and constructive responses, even when the patient’s behaviour has been emotionally damaging, and even when one’s natural reaction is to withdraw or to become defensive. Emotional intelligence is enhanced through a deliberate process of thoughtful, honest reflection and open dialogue.

There may also be times when you need to use emotional intelligence when dealing with challenging nursing colleagues. Students who have highly developed emotional intelligence are more likely to view negative and unreceptive staff with a degree of dispassion, rather than taking the staff’s rebuttal as a personal affront. These students can accept that ‘personality clashes’ are an inevitable facet of working life:

Student experience: It’s learning how to interact with people and deal with people that makes a big difference (Nadeem’s story)

It’s just a case of just getting on with it. I’ve learnt over the years you don’t take their rejection personally; often it’s not a personal thing against you. It’s just that a person’s obviously got issues or something going on in their life that’s making them react the way they react. I don’t take it personally. I just think, ‘Well okay, we’ll just leave that one well enough alone for now’ … I think it’s learning how to interact with people and deal with people that makes a big difference. It’s probably something I would not have been able to do when I started my degree.

4.6 Critical thinking and clinical reasoning

Student experience: Critical thinking in action (Madeline’s story)

A second-year nursing student undertaking a mental health placement encountered a young girl who was experiencing abdominal pain that the nursing and medical staff had attributed to psychosomatic causes. While the nursing student accepted this diagnosis during the majority of her shift it didn’t ‘feel’ right to her and she decided to investigate further. Following a convoluted line of questioning that led to her doing a bladder scan she identified that the girl was in urinary retention with a bladder containing over a litre of urine (in a girl weighing only 45 kg), a known side-effect of one her medications. The student was so proud of herself for her critical thinking ability as were her colleagues. The doctor on duty said, ‘Thank goodness you persevered and found this.’

Something to think about

Something to think about

Thinking leads a man [sic] to knowledge. He [sic] may see and hear and learn whatever he pleases, and as much as he pleases; he will never know anything of it, except that which he has thought over, that which by thinking he has made the property of his own mind.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access