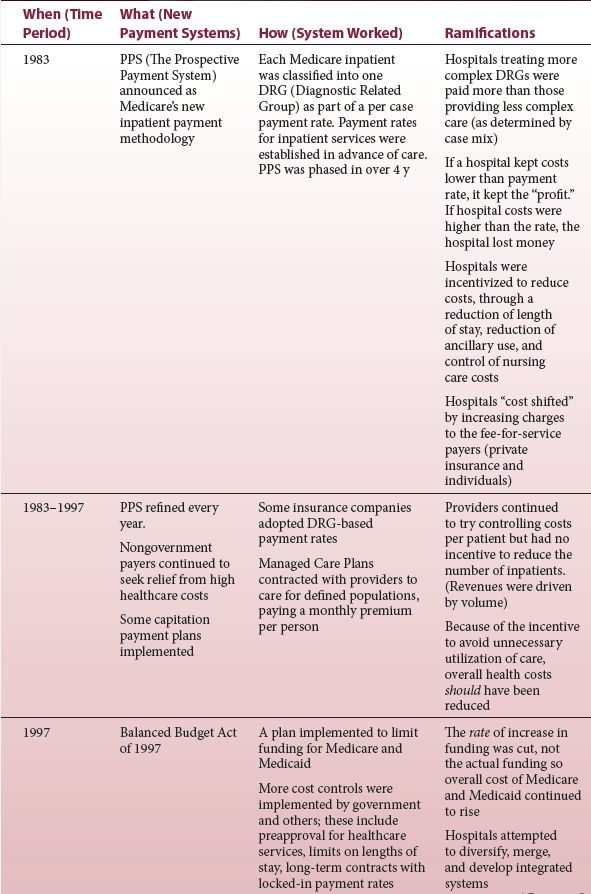

Adapted from Whetsell, G. (1999). The history and evolution of hospital payment systems: How did we get here? Nursing Administration Quarterly, 23(4), 1–15.

When payment models have changed, healthcare providers (hospitals, private physicians, and others) have adjusted their practices to maximize payments like any rational business would do. The regulatory “strings” that come with payments have contributed to both interdependencies among providers and areas of friction and competition.

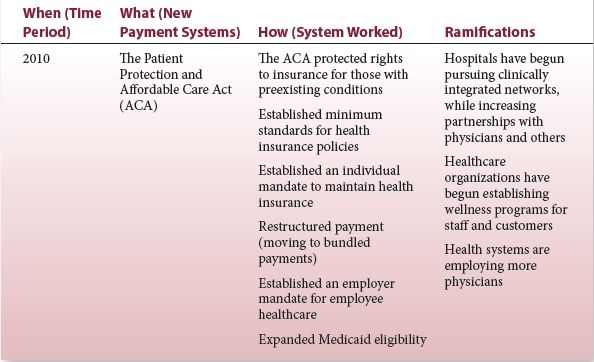

The next era is bringing more payment reform. We are moving away from fee-for-service to outcome-based payment systems. Hospitals and physicians will be paid for value (lower cost for high quality) rather than volume (number of patients, visits, interventions, diagnostic tests, etc.). Instead of being reimbursed for episodic interventions (mostly sick care), it’s envisioned that we’ll be paid as a system for care provided to defined populations. If the future unfolds as planned (and none of us can guarantee that!), keeping people well will be more profitable than treating them when they are sick. Charges for services will become more transparent to customers (who will become more and more the actual users of healthcare and payers). Some leaders believe charges will become much more regulated. (So we won’t find, e.g., the “list price” for an appendectomy ranging from $1529 to $183,000 in the same community.) (12) Bundled payments (that all providers within an integrated network share) will become the common way to pay for healthcare.

Healthcare systems have already begun to respond to these payment changes as we always have—as rational economic entities. We’ll do what we need to be paid for our services. This time, we believe incremental tweaking won’t be enough to change what must be changed if we are to exist through the coming decades.

Nobody knows with certainty what a reformed healthcare system will eventually become. Most of us are convinced we must try new models, in which clinicians and business leaders work closer together to implement coordinated systems. The Dyad leadership model is one strategy to work toward this future.

Dyads and Management Theory

The emergence of Dyads is conceived as a way to manage that will help align the clinical and business side of healthcare. It might also contribute to development of a management theory centered on shared formal leadership.

Bernard Bass, author of a book every graduate student of management should recognize (The Bass Handbook of Leadership), says that “good theories start from one idea or a small set of ideas.” In developing them, “There is a convergence of several interests and activities at the same time … conventional wisdom may be revised or rebased. Research is restated in alternative ways. Established value judgments are challenged. Above all, to be good, theories need to be grounded in assumptions that fit the facts.” In addition, he adds that in theory development, “Intuition and feelings supplement logical analysis” (13).

The development of leadership shared by paired managers from different professions is certainly one intuitive solution for bridging healthcare’s cultural gaps, combining different skills and knowledge for greater problem solving and increasing the span of control and influence of leadership. Two can “cover more territory” than one. Is it also a model supported by previous research? Can it be grounded in assumptions that fit the facts?

Our interest in these questions isn’t because we want to participate in an academic exercise. (We’re a working-more-than-full-time CMO and CNO. We don’t have time for academic exercises or esoteric research). Our purpose is to help organizations who are contemplating the Dyad model determine whether or not it’s a good fit for them. Some might be tempted to say, “These are desperate times that call for desperate measures. Let’s try it and see if it works.” They might find the model intuitively appealing (“Why didn’t we think of this before?”) Or, they might believe that if other organizations are doing this, we should follow suit. (“If it’s good enough for CHI, it’s good enough for us!”)

We believe healthcare systems should answer three major questions before embarking on a Dyad leadership model. Actually, they’re the same questions for every system or process change: Why? What? and How? (After those are answered, of course, the Who? needs to be addressed as well.)

Each of these questions will be answered differently depending on the organization and the management issue to be addressed. (Although much of this book and interest in this model are around Dyads in which one partner is a physician, there are reasons to partner two nonphysician leaders.) The macro “why,” which we assume is predominant for most providers, is the need to align the business (operational) and medical (or clinical) sides of our organizations so we are better partners for the next era of healthcare. The “what” is an implementation of Dyad partnerships. The “how” is the subject threaded throughout this book, including real-life experiences shared in the Dyads-In-Action stories at the end of each chapter.

In this chapter, we are primarily concerned with the “why.” Why are you considering this model? It’s important that you have a problem or issue you really believe will be better addressed by two coleaders rather than one. It cannot be because of a need to pander to the medical staff. (“Look, physicians! You are now in charge, so bring us your patients. You don’t really have to do any managing.”) It cannot be to manipulate. (“Let’s get a doctor coleader in here to help us get those doctors to do what we want.”) If those are the underlying reasons for implementing Dyads, they won’t succeed.

It is true that members of a culture identify with, communicate better with, and trust sooner, someone from their own culture. There is credibility between people who have shared socialization. For clinicians, this is even truer between the subcultures known as “specialists.” Surgeons mostly identify only with other surgeons, for example. A physician dyad member from a specialty that matches her leadership with doctors from the same specialty is a smart hire. For example, an orthopedic surgeon hired as the Dyad physician for the orthopedic service line makes more sense than an ophthalmologist or a general surgeon even though all are physicians who practice surgery.

The “why” for implementing Dyads must include the need to improve value for the organizations. Value is both quality (including safety) and financial success. In addition, organizations will only succeed in bringing cultures together when the objective is a true partnership or uniting of missions and goals. In other words, the Dyad leads a “merger” not a “takeover” of another specialty.

Dyad leadership is not easy. It requires massive change. The successful Dyads, and organizations who implement them, believe in its promise as a true shared leadership. We feel it is the right thing to do in preparation for the next era of healthcare. We also believe that an examination of management theories and research provides some support for the implementation and development of this type of leadership for healthcare.

Dyads are put in place largely (at least this is our assumption) to help bridge the cultural differences between business or operational leaders and clinical leaders. They are contemplated by leaders who believe, as early management educator Chester Barnard did, that “cooperation is essential for an organization’s survival” (14). Their emergence in healthcare, as we are entering an era when we must bring competitive groups together, is validated by research on who can influence others.

Robert Cialdini’s work on influence stresses that “we most prefer to say yes to requests from people we know and like” (15). Who are we most inclined to like? Those who are most similar to us! According to research, including the work of D. Byrne, we like people who share our opinions, personalities, backgrounds, and lifestyle (16). We are most inclined to like (and therefore be influenced by) leaders from our own professional cultures. This is as true for nurses and hospital executives, as it is for physicians. Partnered leaders from different professional backgrounds will have more influences on members of their culture and can help bring their constituents into a new multidisciplinary group, which is better able to cooperate.

Of course, this presumes that the Dyad leaders themselves are able to straddle the gap between two cultures. Can, for example, a strong, respected clinician maintain credibility with his or her medical colleagues while “serving” the goals of a healthcare organization? (This question brings to mind the suit vs. coat discussion in Chapter 1.) Some management research indicates that this is possible and that the most successful leaders are both competent in the eyes of their supervisors and are able to fulfill the expectations of those they lead (17). In fact, as Bass points out “potential conflict may be reduced, avoided, and even resolved because people, who are members of both groups, which have conflicting interests, may consider themselves loyal to both” (13). In other words, clinicians who have been socialized in one culture can learn to be part of another culture and to support both. When they do this, they help both groups cooperate.

Nurse executives have long demonstrated this ability. They balance the organization’s business (financial) needs with quality and safety and the system’s goals with patient and caregiver needs. Physician executives are now being asked to do this, too. Because their relationship and culture have been less aligned with the hospital, there appears to be more trepidation about how well they will be able to do this (Display 2-2).

Display 2-2 A Cultural Phenomenon: Are Physicians Really That Different from Everyone Else?

There are differences in professional cultures, which need to be understood as we learn to work more closely together. However, we hypothesize some differences may be exaggerated. The possibility that some people believe executives think physicians and others are not psychologically similar was brought home to us recently.

Our company hired an expert (from a well-known consulting firm) for education purported to help us better understand physicians as they migrate into employee and employed leadership positions. His presentation title, power point slides, and words all implied that he was imparting information based on research specific to medical doctors. We heard from him that physicians:

1. Must have basic safety needs met before they can become self-actualized.

2. Are not motivated by money. While they are dissatisfied if their pay is not as high as they believe it should be, more money will not motivate them to become team players. They can only be motivated if they feel they are achieving something important.

3. Have four separate areas of self-knowledge. They have traits of which they (and others) are unaware; information about themselves that they know about but others don’t; traits people see in them of which they’re blind; and areas where both they and others are conscious of their traits.

4. Desire to be self-directed and want to exercise their own initiative and responsibility. (Hospitals want to structure physician’s roles and control their actions in order to meet hospital objectives. This causes conflict between physicians and hospitals.)

As each power point displayed on screen, the speaker stated, “Research has shown that physicians … (followed by the points above).” Never was a particular physician-centric study cited. Unfortunately, neither was attribution given to any theorist or researcher, other than recognition that Abraham Maslow is identified with Point 1. We recognized other people’s work though the following:

#1 is the work of Abraham Maslow and his “Hierarchy of Needs” theory (18).

#2 sounds suspiciously like Frederick Herzberg’s Two Factor Hygiene and Motivation theory, in which money (and other work factors) must be present to keep a worker satisfied but only achievement, recognition, growth, and interest in the job motivates him to do more (or change) (19).

#3 is a description of the Johari window developed by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham (that’s where “Johari” comes from—their first names). It’s been widely used to help people from all walks of life understand their relationships, both with themselves and others. Labeled by Luft and Ingham as “Quadrants”, the first (as listed by our speaker) is called to the “Unknown,” the second is the “Façade,” the third is the “Blindspot,” and the fourth is the “Open Arena” (20).

#4 Chris Argyris put forward this theory (the Maturity–Immaturity theory) over 50 years ago! He saw a natural conflict between employees and organizations as a result of this difference in control needs (21).

After the presentation, we puzzled over what we had just heard. Aside from our incredulity that he didn’t appear to think any of the executives in his audience would recognize classic management theories (with the exception of Maslow’s work), the consultant’s “class” left us curious. Why was the speaker hesitant to inform us about the authors of the theories he shared? Why did he appear to want us to believe there is a large body of research specific to the psychology of physicians, as if it differs from research on other employees? Did he believe that executives would not accept anything other than physician-specific behavioral research as credible when applied to medical doctors?

As we pondered these issues, we realized that each of us had been in multiple meetings or discussions in which individuals (both physicians and nonphysicians) have implied that they might believe the last point. They might not accept that research done with factory workers, office workers, or nonphysician leaders could be applied to medical staff members.

As more clinicians become employees and formal leaders, there will be opportunities for research on their behaviors and comparisons with other employees or leaders.

We may be proven right or wrong by these studies, but our belief is, that in spite of professional conditioning, we are more alike than different. Education and increased interprofessional understanding will bridge cultural gaps.

We already know physicians who are successfully bridging the gap between the clinician and administrative world. We believe many more can, and will, do this with appropriate management models in place, as well as careful hiring of individuals who will be asked to adopt a second culture.

Who are appropriate individuals? Some leaders may make the mistake of assuming that they are simply those clinicians who have gone back to school to obtain business education. A growing number of physicians and nurses are obtaining MBAs and MHAs. This business education is wonderful for clinicians and should improve their understanding of the “business tools” side of healthcare leadership. They will be better able to communicate in the language of business and probably have increased expertise in the numerous financial transactions of healthcare. However, business education isn’t enough to ensure outstanding leadership performance by clinicians (or nonclinicians for that matter!) as we move into the next era of healthcare. If we agree that we are in need of transformation, as a system, we need to seek transformative leaders to populate our Dyads (Display 2-3).

Display 2-3 Researcher and Management Expert Descriptions of Transformative Leaders

“A transforming leader raises other’s level of consciousness about the value of goals and the importance of reaching them; gets followers to move beyond self-interest for the sake of the team, organization, or greater good; raises team member’s needs from safety and security to self-actualization.”

—Burnes, J. M. (22)

“Transforming leaders are optimistic.”

—Berson, Y. (23)

“Transforming leaders are not bound by today’s solutions and create visions of possibilities.”

—Brown, D. (24)

“Transformational leaders practice individual consideration for each member of the team. They do this by “telling the truth with compassion, looking for others loving intentions, disagreeing with others without making them feel wrong, and recognizing contributions of each individual regardless of cultural differences.” ”

—Bracey, H.; Rosenbaum, J.; Sanford, A., et al. (25)

“They’ve been shown to raise consciousness of those around them while providing realistic but optimistic views of the future.”

—Bennis, W.; Nanus, B. (26)

“They possess six transformational attributes: articulating a vision, providing an appropriate model, fostering acceptance of goals, setting high-performance expectations, providing support, and giving consideration to individuals.”

—Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Moorman, R., et al. (27)

“They are inspirational networkers, encouragers of critical and strategic thinking, developers of potential, and are genuinely concerned about others, while being approachable, accessible, decisive, self-confident, honest, and trustworthy.”

—Alimo-Metcalfe, B.; Alban-Metcalfe, A. (28)

“Charismatic leaders are likely to be transformational, but it is possible—although unlikely—to be transformational without being charismatic.”

“Transformational leaders raise follower’s level of maturity, ideals, and concerns for the well-being of others, the organization, and society.”

“They stimulate others, think through problems, and teach the skills to do this. They help followers become “more innovative and creative” because they question assumptions and help the team look at old problems through new eyes.”

“They clarify the mission, generate excitement about the work, and show empathy for others.”

—Bass, B. (13)

“Transformational leaders articulate and use visions more than transactional leaders do.”

—Judge, T.; Bono, J. (29)

“They have the motivation to lead, self-efficacy, and the capacity to relate to others.”

—Popper, M.; Mayseless, O.; Castelnovo, O. (30)

“They are more likely to use rational discussion for upward influence rather than ingratiating behavior or strong emotion.”

—Deluga, R.; Sousa, J. (31)

Transformational leadership is practiced by leaders who create visions, shape values, and empower their colleagues to change. Since the 1970s, management researchers and theorists have studied the characteristics of these successful agents of transformative change (Display 2-4).

Display 2-4 Competencies and Behaviors that Correlate Positively with Transformational Leaders

1. Superior cognitive ability or intelligence (Wofford, J.; Goodwin, V.) (32)

2. Good sense (or use of) humor (Avolio, B.; Howell, J.; Sosik, J.) (33)

3. Eloquence (persuasiveness and social sensitivity) (Bass, B.) (13)

4. Superior communication skills (Hater, J.; Bass, B.) (34)

5. Emotional intelligence (Dasborough, M.; Ashkanasy, N.) (35)

6. Intended focus and control (Shostrum, E.) (36)

7. Self-acceptance (Gibbons, T.) (37)

8. Hardness (Kobasa, S.; Maddi, S.; Kahn, S.) (38)

9. Optimism, positive thinking, feeling over thinking (Atwater, L.; Yammarino.) (39)

10. Risk taking (Hater, J.; Bass, B.) (34)

11. Awareness of own emotions (Ashkanasy, N.; Tse, B.) (40)

Much of the literature of transformational leadership contrasts this type of management with “transactional” leadership. Transactional leaders are described as managers who consider their relationships with subordinates or team members as a continual series of transactions. Leaders and “followers” agree on objectives (or leaders solely determine objectives and communicate them). When these objectives are met, team members are rewarded. When they are not met, or standards are not followed, the leader metes out psychological or material “punishment.”

Both types of leadership can be practiced for legitimate reasons even by the same individuals. There are situations when transactions meet the organization’s needs—as when employed physicians are paid by RVUS (Relative Value Units), productivity, or quality standards. However, Bernard Bass, as a compiler of leadership research, points out, “Considerable evidence has accumulated on the greater effectiveness of transformational leadership of politicians, public officials, nonprofit agency leaders, religious leaders, educators, military officers, business managers, and healthcare directors” (13).

Transformational leaders ask others to transcend their self-interests for the good of the organization or society. Bringing together our disparate healthcare cultures will require all of us to put comfort with how things are now (or have been) second to a healthcare system that is better at keeping our communities healthy.

Transformational leaders encourage critical and strategic thinking. We’ll need this as we undertake the next era’s challenge of changing the healthcare system for the entire country!

Transformational leaders develop the potential of team members and genuinely care about individuals. Clinicians, as well as business leaders, need this kind of support to make the kind of change they will personally need to make.

Just as we espouse using clinically evidence-based practices for patient care, it certainly seems we should seek Dyad leaders with either a track record or ability to develop transformational leadership. In Chapter 7, we present methods for identifying who these leaders are. Their job will be to help transform the organization while many must simultaneously transform themselves from membership in a single clinical culture to participation in a dual culture (clinical and system), while learning to colead with a Dyad partner!

It can be done. If you understand our healthcare multicultural history and believe we need to bridge cultural gaps in order to thrive in the future, you are right to consider Dyad management for yourself or your organization.

Chapter Summary

As we move into the next era of healthcare, it’s helpful to review a few points in the history of our professions. This can help us better understand why clinicians (particularly physicians and nurses) and hospital executives have developed differing views of healthcare. For leaders considering the Dyad model, we’ve also presented a rational for why this type of leadership can help move us into the future if we choose the right Dyad partners. We believe these new leaders need to be transformational.

Dyads in Action

Leveraging Our Skills for the Next Era

Service lines are becoming more common as an infrastructure for business and quality provision of a healthcare system’s care. We manage a national oncology service line (NOSL) as a Dyad. Here is our story from the MBA-educated business partner (Deb) perspective and the physician partner (Dax) viewpoint:

MBA: The NOSL was created as an outgrowth of Catholic Health Initiatives’ (CHI’s) participation in the National Cancer Institute’s Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP) at the end of 2009. The NCCCP was a pilot program that started in 2007 with the participation of five CHI cancer centers. CHI found this program to be invaluable to the participating cancer centers and wanted to internally extend these learnings to more of their sites.

One of the recommendations that came from the NCCCP was to have full-time physician leadership at participating sites—something that none of the original pilot sites had. Community cancer centers typically have medical directors who provide clinical guidance ranging from a few hours per month to 0.25 FTE, but very few utilize full-time physician leaders. In the case of CHI, this physician leadership came from a practicing MD who dedicated 0.25 FTE to CHI for national leadership of the NCCCP and 0.25 FTE as medical director at one of CHI’s participating cancer centers. This arrangement was in place from 2007 to 2010, but it was particularly difficult for this surgeon to operate and manage surgical patients 50% of the time, while working in an administrative capacity for two different entities the remaining 50%. After the launch of the NOSL, this balancing act proved even more difficult. When the surgeon decided to take another position out of the area, CHI began to consider other alternatives.

When it was implemented, the National Oncology Service consisted of 10 cancer centers in 8 states, 1 director (me), and an administrative assistant. We received physician guidance through a clinical advisory board of 8 to 10 physician leaders from the system’s markets. They met once a month. This arrangement seemed workable between 2010 and 2012, while the service line grew in size and participation. Physician champions from each site were enlisted for all major initiatives. CHI was lucky to have experienced and knowledgeable physicians from all disciplines who were willing to volunteer their time to champion new programs, such as our Breast and Lung Centers of Excellence. There were many others who joined various work groups to develop policies or adopt new techniques and technology, such as universal screening of colorectal cancers for Lynch syndrome. All of these were valuable contributions but typically involved a defined issue. There was no consistent medical leader considering long-range strategies and overall philosophies of care. As the service line matured, it became evident that an even broader array of clinical standardization and quality initiatives required greater physician involvement on a daily basis.

It became clear that the service line needed a physician as part of our daily leadership. There was a lot of work to be done and we were making good progress, but as time went on, we seemed to be calling for medical leadership more and more from the same group of physicians. I was facilitating physician work groups, but I certainly didn’t have the clinical expertise or the inside knowledge to best address difficult, new areas that we were considering. Something was missing and the more our team looked at our work, the more we realized we needed a physician as part of our team.

CHI already had a dyad partnership at the national level with our CMO and CNO. So we considered: Why not utilize this model in the service line? CHI leadership was supportive of the concept, but the first question raised was whether or not we really needed a full-time physician. Some leaders were concerned that a physician responsible for a service line would need to maintain clinical expertise in order to be relevant and respected by peer oncology providers. Shouldn’t the candidate be expected to practice some of the time and thus maintain his or her licensure? During these discussions, I argued that part-time physician support could no longer be effective for a national service line of our size. During my career, I’d already seen the challenges part-time medical directorships posed for oncologists who tried to practice clinically and also provide administrative leadership. It was very difficult for these leaders to compartmentalize their work day with administrative duties when they were caring for very sick patients. This is a challenge at the community cancer center level, but it becomes an even greater challenge at the national level. Is it fair for a surgeon to operate on a patient and then turn that patient over to his or her partner for follow-up care because he or she needs to get on a plane the next day for a meeting in one of our markets? The issue is equally problematic for a radiation or medical oncologist. Patients who are undergoing treatment for a life-threatening illness want their doctor to be there for them.

There were multiple times that physician champions facilitating a national meeting had to break away from the discussion to deal with an acute patient care issue. Putting the patient first is absolutely the right priority, but we needed someone whose role was to focus completely on the leadership side of cancer. I realized that it would be a challenge for physicians to stop practicing and still maintain their clinical expertise. In fact, all the physician candidates for the new position expressed this same concern. CHI was open to looking at opportunities to develop a solution with our final candidate for my full-time Dyad partner. However, in the year since Dax joined us, no workable solution for staying current in practice while leading the service line has been found, other than attendance at national clinical conferences. To date, the concern about maintaining clinical expertise for our nonpracticing physician leader has not been an issue. He is effective as a service line leader without current patient care practice.

By mid-2012, CHI leadership approved this full-time Dyad leadership approach and posted a position for a 1.0 FTE Physician Vice President for the NOSL who would partner with me in my new role as service line Administrative Vice President. The approval process for this approach turned out to be the easy part. More challenging was finding the right candidate for the job.

Although various physician disciplines could be considered for the position (i.e., pathologist, radiologist, urologist), we were really hoping to find a medical oncologist, surgeon, or radiation oncologist. The service line team felt strongly that the ideal candidate needed to be located in Colorado Springs with the rest of the team … or at least in Denver with the larger national office leadership. In a national organization as large as CHI, many employees and team members work very successfully from remote locations. In this case, however, we felt that in order to build a strong dyad partnership, the two vice presidents (VPs) needed to be able to have face time and in-person working sessions on a more regular basis.

I was nervous that we would have difficulty finding the right candidate. My previous experience as a cancer leader with part-time medical directors was that the physicians provided their input or vision, but I was expected to take complete responsibility for the implementation of those ideas and changes. Part-time medical directors didn’t have time to dedicate to the development of strategies and policies. I was looking for a partner who would not only propose new structures or programs but would also lead clinical teams to make these ideas real. I didn’t want to be someone’s assistant. I wanted a partner and to be half of a team whose skills complemented each other. I already had more work on my plate than I could handle with tons of ideas and opportunities that our limited resources could not address fast enough. I needed someone who would dive in and do the hard work of building programs with me.

MD: Sometimes opportunity knocks when you least expect it. Certainly that was the case for me as I made the leap from bedside doctor to office-based “physician leader.” My decision to pursue a career in medical oncology many years before had been driven by two key observations: (i) the science of cancer medicine was exploding in terms of molecular insights that would radically improve the prognosis for the world’s most dreaded disease and (ii) nowhere in the landscape of healthcare are relationships between doctors and patients more intense or more meaningful than in the field of oncology. With those beliefs in my heart, I completed my hematology and oncology fellowships and enthusiastically entered clinical practice as an employed oncologist in a large community hospital in South Florida. Perhaps without realizing it, I had already made a significant decision that would impact my long-term career trajectory—to be employed by a large institution with a diverse peer group rather than enter private practice. Though economic pressures were already mounting on the traditional independent physician model, that aspect was not a critical factor for me. In fact, there were clearly more lucrative financial opportunities available to me in private practice at the time. I suppose that a part of me already understood that my aspirations were to build a model of cancer care that would require the resources of a health system—a collection of providers, administrators, and others with a shared purpose that went beyond themselves.

As my confidence grew in my ability to connect with and care for patients, so did my need to confront what appeared to be systemic barriers to delivering good care—poor alignment between physicians and health systems, challenges around electronic records that fell well short of their promises, pressure to spend my time almost anywhere except with the patient. Thus, in 2006, I accepted an opportunity to lead the development and expansion of a municipal health system’s cancer program in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In this role, I continued to manage a heavy clinical load but also enjoyed expanded opportunities to materially influence program development, to bring together physicians who shared a common vision, and to advance initiatives that addressed some of the barriers I saw. It was during this period that I was introduced to the model of dyad leadership. We didn’t call it that. It wasn’t a formal structure within the organization. However, the director of the cancer center invited my participation and input in almost all cancer program decision making from day one. That dyad relationship saw unprecedented change and growth in the cancer program through the complementary efforts of physician and administrator. Still, there were challenges. Even as I saw the potential for making even greater impacts on community cancer services, I grew increasingly challenged to give enough to those efforts while meeting the needs of an ever-increasing patient population that needed and deserved my full attention. I could provide vision and some clinical insights but ultimately needed my administrative partner to do much of the ground work. It wasn’t a true partnership.

Enter CHI, a large faith-based healthcare organization undergoing a radical transformation in which true physician–administrative partnerships were being heralded as the model that could meet the needs of the “Next Era” of healthcare. It sounded too good to be true. But as I met with physician after physician within the organization and as I came to understand the resources that were being deployed to develop physicians as leaders, not to turn them into administrators; the more I was intrigued by the opportunity to join this effort. Within CHI, the NOSL was led by Deb Hood, a highly experienced cancer program leader. For the past 3 years, Deb had led a small team that had accomplished extraordinary things across broad geographies: (i) defining a common vision for cancer care across historically distinct and different programs, (ii) mobilization of multidisciplinary care providers to explore and share better ways of caring for patients, and (iii) implementation of IT platforms that would enhance the understanding of the quality and cost of care being delivered. CHI was an organization that was 100% committed to preparing itself to deliver value-based care and manage populations by harnessing the shared skills of administrators and physicians. I found a partner who was accomplished, but genuine in her desire to share leadership with a physician. It still sounded too good to be true. But by this time, I knew that I would have to find out for myself.

MBA: Dr. Dax Kurbegov, a medical oncologist practicing in Colorado Springs, started as the Physician VP for the national service line on December 12, 2012. We wanted a hands-on leader with other skills that would be needed in oncology as health systems transitioned into the next era of population health management. The top five skills (which are likely applicable to other areas) that I wanted for our oncology dyad include the following.

Collaborative but Decisive Leadership

In order to be effective today, leaders need to seek input from experts of all relevant disciplines at the operational level and get buy-in. But, in large organizations, it’s unlikely that there will be 100% agreement and support. Someone needs to make a decision and lead through the ramifications that follow. In a dyad partnership, there are some decisions that clearly belong to either the MD or the MBA; but often times the leadership lines are blurred. Partners need to be comfortable expressing their opinions to each other and determining whether one member compromises or yields to the decision of the other. Once a decision is reached, both members need to be comfortable in supporting that decision and the actions that follow. In order to be effective, a united front is important.

Problem Solving and Constructive Conflict Resolution

The oncology world today is filled with conflict and opportunities to solve problems. There are plenty of issues where both the MBA and the MD need to exercise their skills in conflict resolution. While I have no problem with addressing these issues, I absolutely do not want to always be the bad guy. I need a strong partner who is comfortable in dealing with difficult physician issues. My past experience included physicians who willingly dealt strongly with issues but alienated others through the process. Other physicians wanted to maintain the peace and hoped the problem went away on its own. It rarely did. (Luckily for me, Dax is very pragmatic but extremely skilled in handling these situations. He looks for the mutual win and tries to find common ground. And, when someone is being unreasonable, he doesn’t hesitate to point that out, albeit very diplomatically.)

Innovation

Innovation is prized by all leaders, but national service line leaders need to be open to and actively seeking new ways of doing business. While interviewing for a physician leader, some applicants gave the impression that they were interested in a position where they could comfortably finish out their career. Many did not seem hungry or visionary about what could be accomplished. (Dax was younger than most applicants and had not been practicing as long as others, but he clearly articulated his drive and excitement for what the future could hold.)

Lifelong Learning and Teaching

These skills go hand in hand with “Innovation” above. In order to anticipate future needs, it’s important for dyad leaders to keep abreast of changes in their specialty through articles, conferences, and networking. Many applicants for the physician leader position were clinical experts in their field but had little to no knowledge about changing market forces and trends. While this information could be learned in a new position, it clearly made some candidates stand out from others because they were aware of challenges that they could be expected to deal with. Likewise, a willingness to educate other health providers about these issues in a nonjudgmental manner is key to effective collaborations.

Teamwork

Very few decisions in the oncology service line have been made unilaterally. Teamwork has been the hallmark of our best initiatives. Strong egos on the part of either partner could interfere with effective team participation and leadership. Although the dyad partners are often the team leaders, they also need to know when to listen to the ideas and advice of others, creating truly synergistic collaborations that lead to paradigm shifts in business.

MD: Given the rapidly changing landscape of healthcare, it still remains a great challenge to predict the skill set that will be required to succeed in the future. As I migrated into the role of the physician dyad partner for the NOSL, I spent considerable time reflecting on how I might leverage my clinical experience and background to support our ongoing efforts. I am, after all, who I was trained to be. When confronted by a diagnostic or therapeutic dilemma, I meticulously gather data from as many sources as possible, request additional studies or information to either confirm or refute my clinical suspicions, synthesize that information into a coherent diagnosis, communicate my impressions in a way that is understandable to my audience, and then take definitive action as a partner with my patient. I am and always will be a doc, no matter my title.

While considering what I brought to the table, I also began to appreciate the strengths and success factors that my administrative partner demonstrates each day. Foremost among these is an unwavering commitment to collaborative decision making. Deb’s ability to engage and empower stakeholders is an essential asset in a leader who is guiding others through uncharted territory. Related to this is a focus on teamwork—Deb effectively identifies the strengths of those around her and creates opportunities for them to succeed and grow. But perhaps, the skill I admire the most in Deb is her ability to eloquently articulate a vision that is compelling to others. Inherent in this skill is the ability to understand what matters to the audience in front of her. I have observed Deb in our small NOSL group distill longwinded and sometimes tangential conversations into actionable and straightforward action steps. She is equally adept in large group settings. Early in my CHI career, I had the luxury of appreciating Deb’s ability to reach a diverse group of physicians who had little track record of meaningful cooperation and unify them around a vision of coming together to do cancer research in a novel and integrated way. To paint a picture compelling enough to move physicians out of the comfortable fiefdoms that they are used to operating within is a significant accomplishment.

MBA: Soon after starting with CHI, Dax scheduled visits to many sites to meet key physicians. One of the things I’ve been so impressed with is his ability to develop positive working relationships with so many physicians in a short time. That early work laid the foundation for difficult decisions and tough conversations in later months. Dax is able to pick up the phone and have very frank and supportive conversations about complicated subjects. He is able to positively work toward a conclusion without alienating anyone. I also think that of the two of us, he is much more the diplomat. I’m not saying we play “good-cop/bad-cop” roles, but when I’ve been fired up about something, he has a great way of stepping in, calming everyone down, and refocusing us on the big picture.

One of the challenges with dyad leadership is determining whether one or both of us need to be involved. Constant communication is key. It’s easy to include the dyad partner in all e-mail communications on critical subjects although this can lead to an enormous number of e-mails that are tangential to the work at hand. While both parties want to stay aware of the key issues, it’s also important to communicate with each other if someone wants to step out of the loop and let the other take the lead. Dyad leadership communication can also be a challenge for our widespread facilities sites and departments. Sometimes they are not sure if they should communicate with one or both parties. We’ve tried to keep each other in the loop without overloading the other but we also try to decide and articulate up front which of us will take the lead.

It’s important to be cognizant of whether both parties or just one of us needs to be present at meetings and phone calls. It’s neither cost- nor time-effective to always have two people covering the same issue. But, there are many situations where each leader brings a unique set of skills to the discussion and both should be present. The only way to address this is to constantly be aware of the need for efficiency and effectiveness. This model will be most successful if each leader uses his or her skills to cover a large territory of work while maintaining strong communication with his or her partner.

The right partnership means that both leaders truly act as a one. Each covers different areas based on the individual’s interest and/or expertise, but the service line goals remain the top priority. A true partnership means supporting each other’s decisions, consulting constantly with one another, having each other’s back, and trusting that both are acting in the best interest of the organization.

MD: As I entered the equation, the NOSL had been in place for several years working on an array of initiatives ranging from quality metrics to physician alignment to information technology infrastructure. To join this group, which had long track record of working effectively with one another and with cancer program leaders around the country, posed a number of challenges. How does accountability change within the team when a new dyad partner is introduced? How do stakeholders outside of the immediate team come to understand to whom they should direct queries? How would I effectively support Deb and the team when I had such a profound deficit around organizational intelligence compared to the rest of the group? The key to successful integration rested in frequent and effective communication between Deb, myself, and other key leaders within CHI as well as the development of a learning plan that offered me the opportunity to gradually expand the scope and depth of my involvement in service line initiatives.

Like many coming into a new leadership role, I was challenged to temper my intrinsic desire to be immediately impactful. Considerable discipline was required to recognize that our NOSL had been performing at a high level under Deb’s leadership for an extended period of time and that if I attempted to alter internal team dynamics or external team dynamics too quickly I risked disrupting ongoing priorities and introducing confusion where previously there had been clarity. Thus, in the first few months with CHI, my attentions were most clearly focused on those activities where clinical insights were critical for success. Prior to my arrival, this role had been filled by our physician advisory group that met monthly. However, clinical questions frequently arose that required immediate answers to keep the project progressing. Providing timely clinical insight and assisting the NOSL team in prioritizing clinical projects based on potential impact allowed me not only to make contributions from the start but also to begin to understand how roles and responsibilities had evolved within the team. A critical aspect of this work was that it allowed me to begin piecing together how individual projects supported a long-term, larger vision and how I could add my own ideas to that vision. As I became more familiar with the projects, I also had the opportunity to better understand how our NOSL team interfaced with other national leadership groups at CHI and with our cancer program leaders out in the markets. In parallel with this effort, I began to establish and develop relationships with physician leaders across CHI through a series of purposeful and coordinated site visits. Recognizing that a critical success factor for me would be the ability to credibly relate to and represent our cancer physician leaders, Deb and I identified specific markets and program leaders for early contact. This element of my learning plan provided key contact points across the organization and also provided me with an outside perspective on the perceived value and effectiveness of the NOSL group.

Organizational IQ was another important focus of learning. Rather than detailed explorations of every individual active initiative, Deb and I scheduled a series of conversations around CHI structures and processes as well as around current major challenges for cancer care providers in each market. Key leaders at the national level were identified for extended dialogues, providing greater clarity to me about their roles and priorities as well as creating a peer group of both physician and administrative leaders on whom I could call if I had need. Of course, Deb’s 35 years of experience within the organization has always made her an ideal partner to whom I could direct organizational questions. One example of where such interdependence is vital involves our exploration of decision support tools. As the amount and complexity of data that oncologists must process to make the best decisions for patients increases, a number of third party tools are being developed to help streamline decision making. Whereas my background made me well suited to evaluate the utility of such clinical pathways, I was equally ill-equipped to navigate CHI’s multifaceted information technology groups, governance groups, project management resources, and processes for evaluating such applications. Through frequent and targeted communication with Deb, I could move the project forward while receiving timely guidance on how best to mobilize national resources to support the effort. After a year in my role, I have much greater command of how to get things done within CHI. However, given the size and complexity of the organization, I continue to rely on my dyad partner as a key source of organizational insight.

For dyad partners to effectively lead, it is essential that both partners commit not only to frequent communication but also to investing the time to better understand each other’s communication styles and needs. I have always admired Deb’s ability to move quickly and confidently from discussion to action. However, in my early days with CHI, I sometimes felt that we were making the transition from exploration to implementation without all of the data. I sometimes found myself deferring to others within our group out of respect for their experience within the organization. Sometimes this felt more like we had moved on before I had made my contribution. It caused me distress because I felt I had more to offer and I believe it may have caused distress to others, as they might misinterpret my lack of passionate discourse as ambivalence. We were communicating openly, we had a shared vision of where we were going, and we had a great deal of trust. But still, something was off. For me, the light went on during a 3-day conference where both NOSL leaders and our oncology dyad leaders from the markets participated in a leadership seminar focused specifically on the dyad model. Though this was originally intended to be primarily of value to the market dyads, the focused time dedicated to communication and leadership styles provided valuable insights that would enhance my ability to work with Deb and other NOSL members. These insights were about me—my need to diligently collect data and differing viewpoints, my desire to process that internally before rendering judgment, and my preference to move slowly but without error. They were also about my dyad partner—Deb’s ability to offer strong input early in conversations, her desire to drive action, and her willingness to course-correct on the fly. Without an understanding of our innate styles, I believe there would have been opportunity for friction and frustration. By moving through this purposeful exercise, we took an important step to a better understanding of how our styles could be complementary. This type of leadership exercise may be extremely valuable in the context of the dyad leadership model, especially if early endeavors don’t meet expectations.

MBA: Dax’s insights about different leadership and communication styles are spot on. Finding out about these similarities and differences between dyad leaders is an important exercise that should be explored early in the partnership. We are fortunate that our styles are very different. If my partner worked in a style identical to mine, we may not be as successful as partners. Because we are different, we provide different perspectives, varied decision-making styles, and different analyses of situations. Whatever the similarities or differences within the dyad partnership, awareness and balancing the strengths, challenges, and workplace preferences of each other is critically important.

MD: At this time, I find my dyad leadership role to be among the most professionally satisfying of my career. While there are still many opportunities for improvement, I have not felt my independence or autonomy compromised; a fear common among physicians asked to share in leadership roles. To trust and collaborate with another who brings a unique perspective and different set of skills can be immensely rewarding. The model lends itself to lifelong learning because we can safely and collegially challenge one another on a range of topics. It is quite clear to me that this partnership creates an opportunity to accomplish together more than either of us would achieve on our own.

MBA: Dax has been a Godsend, and everything that I wished for in a physician leader. I truly didn’t know what we were missing and how much more effective our team could be until he joined our group. My fears around the dyad leadership model have been unfounded. I am amazed at the positive impact that Dax made to the NOSL in a very short period of time. Several difficult initiatives that had been stalled have been completed or are well on their way. There are so many changes occurring today with initiatives that require clinical AND business leadership. In my mind, this is the only way to create significant and sustainable change across the cancer world.

Key Success Stories

The following five topics are a sample of areas where we, as the oncology dyad, have realized the benefits of each other’s unique skills and focus. Each leader contributes our own strengths, which provide a better overall picture of the situation along with ways to address challenges.

Physician Alignment and Engagement

The benefits of physician leadership in this arena are a “no brainer.” Physicians often relate one to one with their peers more effectively with nonphysician healthcare administrators. A physician leader understands intimately the clinical and business challenges of running a practice. Dax is able to call and reach physicians quickly to discuss various issues. It’s much more common for Dax than for Deb to receive a timely call back from a physician that he has never spoken with before. (Deb needs to explain in more detail who she is, the organization she is calling from, and what she is calling about, not only to peak the physician’s interest but also to keep staff gatekeepers from interpreting this as a “sales call.”)

Over the past year, we’ve been involved in various discussions on new physician models in our communities. Because Deb has been with the organization longer and knows more of the history in the facility/physician relationship, she often knows the key CHI players who need to be involved, as well as some of the contractual, financial, and legal aspects of various models. Dax is able to provide the physician perspective and connect more effectively with physicians in discussions. Together, we’ve been able to propose win–win situations for all parties.

Clinical Research

The National Cancer Institute announced formation of a new program, NCORP (National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program), at about the time Dax joined the service line. CHI began investigating facility interest in developing a CHI national research structure that would meet the NCORP requirements. Conference calls and meetings were held to determine interest, and as a team, we were immediately able to engage and organize physicians in each market. Dax’s interest and experience as a physician conducting research was key to developing a physician work group that defined the physician’s role in this large national network and determined work flow for selecting clinical trials, developing a robust portfolio of studies, and identifying physician experts and leaders who could interface across the network, with research bases and academic medical centers. Dax and other physicians developed the physician conditions of participation for this network, which defined research expectations of participating physicians. Similar documents have been developed in the past for other areas in Oncology, but administrative leaders found that implementing these types of documents took months to years of work before physicians agreed to the format and content. With a physician leader, these documents were quickly agreed to and implemented across the network.

Quality Initiatives

Dax’s presence on the NOSL team has provided stability for the team regarding clinical guidance, overall strategy and philosophy related to oncology quality initiatives. While physician champions are still needed, because a single physician cannot lead all the initiatives CHI currently has in play, Dax is instrumental in the long-range planning and organization of major initiatives. Since the inception of the service line, nonphysician team members have successfully implemented numerous quality initiatives. Discussions of clinical standardization and pathway development were postponed, however, as team members didn’t feel they had the appropriate skill level to make these decisions. A single physician champion from one market would also have a difficult time, on a part-time basis, leading a complicated initiative such as this. It requires focused attention and a great deal of ongoing work over an extended timeframe. Although this type of work is still difficult and quite time consuming, Dax has successfully moved the organization ahead in these areas.

Electronic Health Records/IT

The NOSL is implementing an oncology-specific electronic health record (EHR) in our outpatient medical and radiation oncology practices. Deb has led this initiative since 2010. At every implementation, physicians have felt very challenged with the workflow changes they encounter as well as the increased time required from them to input data. The changes have been most profoundly felt in practices moving from paper records to their first EHR. Dax’s presence on the team doesn’t change the situation itself, but he has invested the time to talk individually with physicians and listen to their concerns. Often, he is able to provide insights to the applications team that can help with the difficult transition.

Data Analytics and Management

This is an area where together, both leaders have contributed toward a better, combined understanding of what is needed. Dax has greater depth in the clinical aspect of DRGs, CPT codes, and procedural parameters along with a quality tracking focus. Deb’s focus, on the other hand, is on the business, acquisition or infrastructure of the data. The level of data management and analytics required today in oncology is beyond what either leader has experienced in the past. Together, along with other team experts, we’re finding our way forward in building oncology data marts, pulling structured and unstructured data into meaningful information, and gathering vastly improved information that can drive quality decisions and outcomes. This is uncharted territory where two heads and two different perspectives can propel the organization forward.

Our Dyad is a true leveraging of two sets of skills. We’re believers in this model of management. We also believe we are making a difference for patients and those who care for them in a time of great change. We are fortunate to be part of a transformational era and to be leading together.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree