Chapter 9 HIV prevention

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges facing the world today is the control of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. At the end of 2009 an estimated 33.3 million people were living with HIV [1]. While intravenous drug use is the major route of transmission in several countries, sexual transmission is the dominant mode of HIV spread globally, with a concomitant epidemic in infants born to HIV-infected mothers. Although many regions and countries are showing signs of declining or stabilizing epidemics, some countries still have unacceptably high HIV prevalence and incidence rates. In contrast to the first two decades of the HIV pandemic, today women comprise about half of all adults living with HIV/AIDS globally [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa, young women aged 15–24 years are as much as eight times more likely than men to be HIV-infected.

Preventing Sexual Transmission (Box 9.1)

Reducing sexual transmission, especially heterosexual transmission, of HIV is critical to altering the current epidemic trajectory in many parts of the world. Prevention of sexual transmission can be achieved through reduction in the number of discordant sexual acts and/or reduction of the probability of HIV transmission in discordant sexual acts [2].

Box 9.1 Evidence-based HIV prevention strategies

For sexual transmission:

• Behavior change programs, including school-based sex education

• Male and female condom promotion

• Antiretroviral microbicides for prevention of male-to-female transmission

• Oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of male-to-male transmission

• Integration of behavioral prevention programs into AIDS treatment services (prevention for positives)

For mother-to-child transmission:

There is no risk of sexually acquired HIV infection among individuals who practice sexual abstinence or lifelong mutual monogamy. Serial monogamy, where there are multiple sequential individual short-lived monogamous partnerships, is associated with an increased risk of HIV, but not to the same extent as the increase in risk of transmission emanating from multiple concurrent sexual partnerships [3]. Reduction in the number of concurrent sexual partnerships and the use of condoms are key components of HIV prevention messages, widely promoted as part of “ABCCC” campaigns promoting Abstinence, Be faithful, Condomize, Counseling and testing, and Circumcision.

Abstinence

Abstinence is a HIV prevention strategy promoted primarily for adolescents and entails either delaying sexual initiation or practicing “secondary abstinence,” which is a prolonged period without sexual activity amongst those who have previously been sexually active [4]. The impact of abstinence on HIV prevention appears to be limited, with short-lived success despite the widespread implementation of abstinence messages. In settings where the epidemic is generalized and probability of infection is high because of high disease burden, postponement of sexual initiation in women simply delays the age of infection, but does not in itself reduce rates of infection [5]. Regardless, abstinence remains an important component of HIV prevention in youth, especially targeting delaying sexual debut.

Be faithful

Individuals with multiple partners may face an increased HIV risk due to overlapping sexual relationships, although gender and other factors such as overlap duration, sexual frequency, and number of people with overlapping partnerships strongly influence this association [6–8]. The link between concurrent relationships and HIV risk is particularly relevant in sexual partnering between younger women and older men [9], which is a major factor in HIV spread in southern Africa.

Condoms

Condoms are inexpensive and relatively easy to use and provide protection against acquisition and transmission of HIV, a wide range of other sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy. When used correctly and consistently, the latex male condom is highly effective in preventing the sexual transmission of HIV. Although numerous studies conducted over the past decade have demonstrated the steady increase in acceptability and use of male condoms [4, 10], a review of HIV risk studies [11] estimates that only about 20% of adolescents use male condoms consistently.

To be effective as a prevention option and to impact on the growth of the epidemic, access to condoms, especially female condoms, needs to be drastically scaled-up. In addition, barriers to condom use need to be addressed; some of the most common being: the widespread perception that condoms reduce sexual pleasure and that suggesting the use of condoms represents self-acknowledgment of HIV infection or a lack of trust in the partner [12, 13]. Some studies have found that young people may also associate condom use with promiscuity and sexually transmitted infections including HIV/AIDS [14]. In the context of a marital relationship or stable partnership where pregnancy is desired, or where subordination of women limits their ability to negotiate safer sex practices, attempts to introduce or promote condom use have had limited success.

Counseling and testing

HIV counseling and testing has been shown to be both efficacious in reducing risky sexual behaviors [15] and cost-effective as a prevention intervention [16]. Knowledge of HIV status is an important gateway for targeted prevention and care efforts. It creates an opportunity for addressing prevention efforts along a continuum that includes those uninfected who are at high risk of getting infected, those recently infected, those with established infection but asymptomatic, those who have advancing HIV disease, and those on antiretroviral treatment. However, large numbers of people, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, are unaware of their HIV status [17]. A study in the USA has shown that individuals who are unaware of their HIV infection are 3.5 times more likely to transmit the virus to others than those who know about their infection [18].

Medical male circumcision

Medical male circumcision is a proven HIV prevention option for men [19], reducing the risk of female-to-male transmission of HIV by up to 60%. Although this prevention option took some time to be incorporated in the HIV prevention package, widespread use of medical male circumcision to reduce HIV risk is fast gaining momentum, particularly in sub-Saharan African countries. For example, in Kenya and Botswana, policies to have 80% of 0- to 49-year-old HIV-uninfected males circumcised by 2013 and 2014, respectively, have been approved [20]. It is estimated by mathematical modeling that widespread implementation of male circumcision could avert between 2 and 3 million HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa [21].While women do not gain a direct benefit from circumcision of men, they derive an indirect benefit over time as fewer men become infected with HIV. Medical male circumcision of HIV-infected men does not seem to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition in their female partners. Similarly, medical male circumcision does not demonstrate protection against HIV transmission in men who have sex with men (MSMs).

STD screening and treatment

An estimated 340 million new cases of curable sexually transmitted infections occurred globally in the 15–49 years old age group in 1999 [22]. HIV transmission and acquisition during heterosexual intercourse is enhanced in the presence of sexually transmitted infections, particularly ulcerative infections such as syphilis, chancroid, and herpes simplex type 2 virus infection [23, 24]. Despite the promising 42% reduction in HIV incidence rates observed in a randomized controlled trial conducted in Tanzania following treatment of sexually transmitted infections [25], other similar studies have failed to replicate these results [26]. Notwithstanding the inconsistent findings from these trials, the significant sexual and reproductive health challenge posed by the high burden of curable sexually transmitted infections needs to be addressed in any HIV prevention effort.

Antiretroviral microbicides for prevention of male-to-female transmission

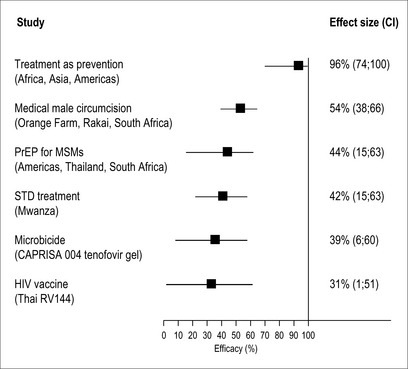

The search for a female-controlled prevention option has been ongoing since 1990 [27]. In 2010, the CAPRISA 004 trial showed that an antiretroviral drug, formulated as a topical vaginal gel, prevents male-to-female transmission of HIV. In this trial, tenofovir gel, used before and after sex, reduced HIV acquisition by 39% [28].This trial has contributed to the growing body of randomized control trial-based evidence for preventing HIV sexual transmission (Fig. 9.1). It is anticipated that a licensed product will be available by 2014. Although tenofovir gel will not provide complete protection against HIV, it still has the potential to have an enormous public health benefit. In South Africa alone, this new prevention technology could avert an estimated 1.3 million new HIV infections and 800,000 AIDS deaths over the next 20 years [29].

Oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of male-to-male transmission

Oral antiretroviral drugs used as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) have recently been shown to successfully reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV. The iPrEX trial showed that Truvada (a combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine) taken daily reduced HIV acquisition by 44% in men who have sex with men [30].

Since Truvada is already a licensed antiretroviral drug for AIDS treatment, its widespread implementation as HIV prevention among men who have sex with men began in 2011. Based on the results of the iPrEX study, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other US Public Health Service agencies have issued guidance on the use of PrEP among MSMs at high risk for HIV acquisition in the United States as part of a comprehensive set of HIV prevention services [31].

However, oral PrEP has not yet been shown to be effective in other at-risk populations. A trial assessing the efficacy of Truvada as PrEP in women was prematurely halted in April 2011 [32] as it was considered futile to continue the trial following an interim analysis that showed no protection against HIV infection. Several trials in discordant couples, women, and injecting drug users are still ongoing.

If successful, scale up of PrEP will require integration into existing HIV prevention services, which currently need to be strengthened, especially in Africa, where the need is greatest. Similar to microbicides, implementation of PrEP will require long-term follow-up and surveillance for monitoring adverse events, adherence, drug resistance, impact of drug resistance on later AIDS treatment, and risk compensation/behavioral disinhibition. The potential contribution of PrEP to drug resistance may not be as severe as originally thought. Mathematical modeling of the impact of antiretroviral therapy and PrEP combined on HIV transmission and drug resistance has shown that while prevalence of drug resistance is anticipated to increase to a median of 9% after 10 years of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and PrEP rollout, most of the new drug resistance is anticipated to be from ART of HIV-infected patients rather than PrEP[33] in HIV-uninfected people.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree