OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a viral infection that is transmitted from person to person. Over time, HIV overburdens the immune system’s ability to coordinate an effective response against infection. This erosion of immune function takes years to occur; the eventual state of disintegrated defense against opportunistic infections is called acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Without antiretroviral treatment, HIV infection is almost universally fatal.

Since the immune deficiency syndrome associated with HIV was first described in 1981, great strides have been made in care and treatment of persons living with HIV. Nevertheless, HIV has claimed more than 25 million lives in the past 30 years and approximately 34 million persons were living with HIV in 2011 globally. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that more than 1.1 million persons are living with HIV.

Transmission and Development

Etiology and Pathophysiology

At the beginning of this epidemic, AIDS affected men who had sex with men (MSM), persons who shared needles when using intravenous drugs, persons who received large-volume transfusions of blood or blood products, heterosexual partners of infected persons, and children of infected mothers. Today, the majority of new HIV infections are found among MSM, and disproportionately among racial minorities and transgender persons. Others at risk include injection drug users (IDU), African Americans, those having heterosexual sex, and women. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States is reduced to <2%, owing to aggressive HIV testing, antiretroviral treatment of pregnant women, and other interventions in the intrapartum and postpartum period. Transmission from donor blood is very rare.

HIV enters the body through unprotected sexual contact or blood-to-blood transmission, then targets immune cells that carry CD4+ receptors, namely T cells and macrophages. Once inside the host cell, HIV uses the cell’s components as a factory to reproduce. Eventually, reproduction of HIV within the host cell ruptures the cell membrane, releasing into the plasma more HIV virions that bind to and disable other CD4+ cells.

HIV infection may be viewed as a chronic condition if patients strictly adhere to treatment and care. However, some patients have difficulty managing highly structured medication and appointment regimens and need encouragement or

special interventions to support their treatment plan. Nursing care is important to tailoring a plan with the patient that optimizes her or his chances for successful and enduring treatment.

Natural History of HIV Infection

Evidence Base U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau. (2011). Guide for HIV/AIDS clinical care. Available: http://hab.hrsa.gov/deliv erhivaidscare/clinicalguide11/.

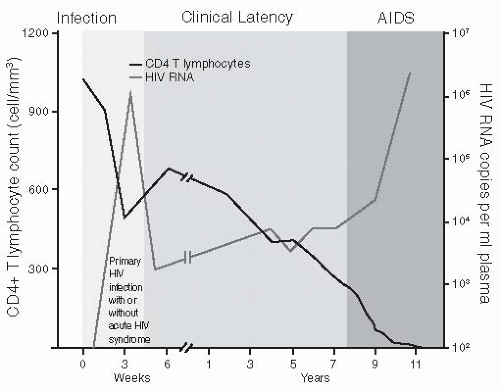

Approximately 50% to 90% of patients who become infected experience some symptom of primary HIV infection around 2 to 4 weeks after exposure to HIV. Typical symptoms include fever, adenopathy, pharyngitis, and rash. Many new HIV infections evade diagnosis because symptoms of acute HIV infection mimic other common infections. Recently, more persons who present to urgent care with these symptoms receive HIV testing and diagnosis. During this phase, the immune system is compromised by a sudden decrease in T4 helper cells and an increase in HIV viral load for a brief period before settling into a new baseline.

Seroconversion occurs when the person has formed enough antibodies to HIV that the serologic test is positive. This usually occurs 4 to 6 weeks after acute HIV infection.

The CDC provides a mechanism for staging HIV infection and defining the continuum to AIDS using clinical findings and the CD4

+ count (see

Table 29-1). A normal CD4

+ count is 800 to 1,000/mm

3. Because HIV replication destroys CD4

+ cells, the number of these cells diminishes slowly over time.

Waning immunity in persons with untreated and treated HIV infection allows development of frequent infections, severe opportunistic infections, and malignancies. These usually appear years after exposure to HIV (see

Figure 29-1).

Clinical Manifestations of HIV/AIDS with Advancing Infection

Diagnostic Evaluation

HIV Testing

Description

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)—serologic test for detecting antibody to HIV. Western blot test is used to confirm a positive result on ELISA.

Rapid test (serology or oral sample)—15- to 40-minute result; used in settings where patient is less likely to return for result such as mobile van, emergency department, urgent care center, or STD clinic.

Antibodies to HIV generally take 2 to 12 weeks to develop. Therefore, a negative-HIV antibody test may catch a person within this 12-week time frame to HIV seroconversion, known as the window period.

Nursing and Patient Care Considerations

Occasionally, an ELISA screen may yield an indeterminate result by Western blot.

The cause of an indeterminate result may be early HIV seroconversion, HIV vaccine, infection with O strain or HIV-2, or a false-positive in a low-risk individual.

The test should be repeated at 1, 2, and 6 months until Western blot becomes positive or there is no longer suspicion of HIV infection. If a conclusive test is needed quickly, HIV RNA viral load testing can be done.

The CDC recommends opt-out testing for HIV for persons age 13-64, which requires general medical consent for testing and optional prevention counseling.

Other Laboratory Tests

Lymphocyte panel may show decreased CD4+ count. In early infection or in long-term nonprogressors, CD4+ count may be normal.

A complete blood count (CBC) may show anemia, low white blood cell count, and/or decreased platelets.

Presence of indicator infection through microbiology or serology testing (eg, PCP, candidiasis of esophagus, herpes zoster).

HIV viral load testing is a measure of the amount of HIV in the blood. High viral loads (>750,000) tend to be found in acute seroconversion and late infection, but also occur in patients who have a concurrent infectious process. A viral load test result can be undetectable, meaning the amount of virus is less than the limit of the test, which may be either <400 or <50 copies/mL.

Resistance testing is done to determine if the patient is infected with a drug-resistant virus. The test uses genotypic assays that amplify the HIV virus and look for mutations in the viral genotype, which represent changes that block or impair the effectiveness of specific antiretroviral agents.

Evidence Base

Evidence Base NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERT Evidence Base

Evidence Base Evidence Base

Evidence Base NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT Evidence Base

Evidence Base