Chapter 40 HIV disease among substance users

treatment issues

Epidemiology

HIV/AIDS and illicit drug use adversely impact tens of millions of people, with explosive epidemics of both described worldwide. Non-injection drug use such as alcohol and stimulant use (e.g. cocaine and methamphetamines) contribute to risky sexual behaviors leading to HIV acquisition [1]. Injection drug use (IDU), largely of opioids, has been reported in 136 countries and 114 of these have reported HIV cases [2]. The link between drug use, particularly IDU, and HIV has been well described since the beginning of the HIV pandemic [3]. The world’s most volatile and emerging HIV epidemics are in areas that are fueled by illicit drug use, particularly heroin. New IDU epidemics continue to emerge with some of the newest in Kenya and Tanzania. Recently, HIV seroprevalence of 42% has been reported among 534 male and female injectors in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania [4]. Particularly troubling is that many of these epidemics are among individuals younger than 30 and within the most densely populated regions of the world. Injection drug use is especially important in the HIV/AIDS epidemic among women and children.

In light of the increasingly central role of drug use, particularly IDU, in the global HIV/AIDS epidemic, issues of HIV clinical care and therapeutics in this population are of great importance. Of particular relevance are the special clinical features of HIV disease in drug-dependent patients, the treatment of HIV disease itself in this population, the special difficulties in providing care to drug users and the treatment of drug addiction and special issues of HIV prevention [5].

HIV Disease in Drug Users

The natural history of HIV disease among drug users has been demonstrated to be similar to that in other transmission risk categories [6]. Drug users are, however, at an increased risk for a number of other infections compared with other risk categories. Although most of these infections and other complications were common among drug users prior to the HIV epidemic, their incidence and severity have been accentuated, and clinical presentation affected by HIV infection. In both inpatient and outpatient settings, these are more common than the designated AIDS indicator diseases or specific HIV-related complications and often confound both diagnosis and treatment [5].

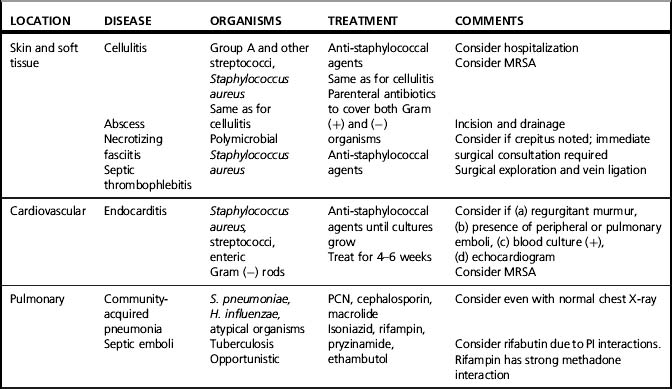

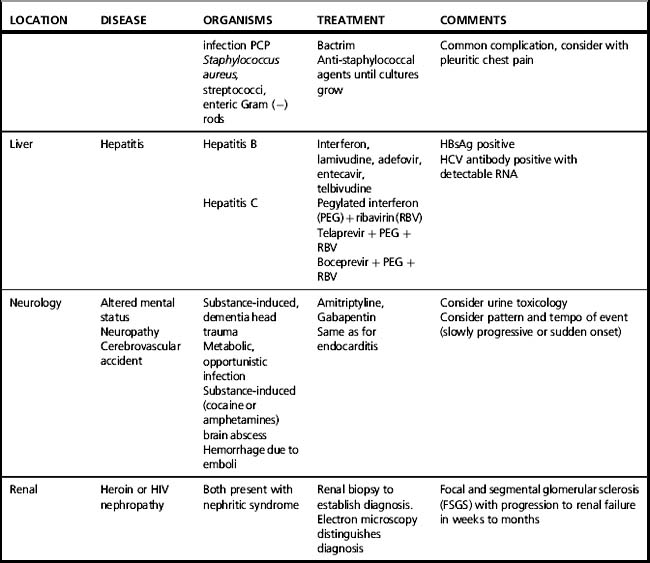

Multiple features of injection drug use that contribute to the increased risk of infection are summarized in Box 40.1, A detailed discussion of these infections and their management is beyond the focus of this chapter. Table 40.1 offers a summary of substance use-related complications in HIV-infected injection drug users. This chapter will address specific issues for co-managing and treating HIV infection itself among users of illicit drugs.

Box 40.1 Features of injection drug use (IDU) contributing to the infectious diseases listed in Table 40.1

1. Increased rates of skin, mucous membrane, and nasopharyngeal carriage of pathogenic organisms.

2. Unsterile injection techniques.

3. Contamination of injection equipment or drugs with microorganisms that may be present in residual blood in shared injection equipment.

4. Humoral, cell-mediated, and phagocyte defects induced by HIV infection and/or drug use.

6. Impairment of gag and cough reflexes due to intoxication resulting in increased risk for pneumonia.

7. Alteration of the normal microbial flora by self-administered antibiotic use.

8. Increased prevalence of exposure to certain pathogens (notably Mycobacterium tuberculosis).

9. Concomitant behaviors such as cigarette smoking (i.e. increased susceptibility to pulmonary infections), alcohol use (i.e. increased progression of hepatic fibrosis for HCV-infected drug users), or exchange of sex for drugs or money (i.e. exposure to sexually transmitted infections).

10. Decreased access to and/or lack of appropriate use of preventive and primary healthcare services.

Treatment of HIV Infection in Drug Users

Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has resulted in impressive benefit for people living with HIV/AIDS, including decreasing morbidity, mortality, and hospitalization, and has been demonstrated from a societal perspective to be cost-effective [7]. Despite the widespread availability of antiretroviral medications in resource-rich settings, IDUs have derived less benefit than other populations. This disparity in benefit among IDUs has been and will likely continue to be experienced in resource-limited settings even as cART becomes increasingly available for adults and children with HIV disease. The reasons for the disparity are multifactorial.

In many societies worldwide, both HIV and illicit drug use are stigmatized such that either or both conditions are often cloaked in secrecy and may result in a lack of detection and treatment [8]. Drug users are among the most socially marginalized populations and often hidden by circumstances and/or choice from mainstream medical care. Even when available, healthcare services are often constructed in ways that are difficult for many drug users to access, either by their absence in communities with high prevalence of drug use or by their organization that does not accommodate the chaotic and sometimes unpredictable use of services characteristic of drug-using populations. In addition, clinical care for drug users with HIV disease is often challenging and stressful for clinicians and other healthcare workers as a result of the complex array of substance misuse-related medical, psychological and social problems. The frequent co-morbid underlying psychiatric disease often contributes to these difficulties. Substance misusers may also have increased difficulties with adherence to cART, which may be compounded by their underlying co-morbid diseases, increased side effects, and drug interactions.

Because the life of a patient struggling with substance use disorders (SUDs) is often chaotically organized around their substance use needs, successful programs for this population have developed some or all of the following characteristics: (1) pharmacologic (e.g. methadone and buprenorphine programs) and/or non-pharmacological treatment (e.g. 12 steps) for SUDs; (2) flexible outpatient and community care settings (e.g. walk-in clinics, mobile healthcare programs); (3) low-threshold sites to engage active users (e.g. syringe exchange sites); (4) modified directly observed therapy; (5) intensive outreach and case management services; or (6) treatment during incarceration [5].

Clinicians involved in the care of drug users with HIV, should be aware of several key principles, which include the following: (1) Become educated about substance abuse and its wide array of treatment options. (2) Establish a multidisciplinary team of individuals with expertise in managing HIV, substance abuse, and mental illness, and broadened to include social work, nursing, case management, and community outreach. Identify a single provider to maximize consistency. (3) Obtain a thorough history of the patient’s substance abuse history, practices, needle and syringe source, drug abuse complications, and treatment history. Non-judgmental, clinical assessment of this information is essential. Non-judgmental discussion of the adverse health and social consequences of drug use and the benefits of abstinence may increase the patient’s understanding of his or her disease and interest in change. (4) Be aware of pharmacological drug interactions between HIV therapies and substance abuse therapies and provide simplified, low pill burden regimens to improve treatment adherence. (5) Link HIV and substance abuse treatment goals such that success in one arena is linked to improved outcomes in the other. (6) Establish a relationship of mutual respect. Avoid moral condemnation or attribution of addiction to moral or behavioral weakness. Acknowledge that SUDs are medical diseases, compounded by psychological and social circumstances. As such, they should be treated using evidence-based guidelines with a combination of pharmacological and behavioral interventions. Reducing or stopping drug use is difficult, as is sustaining abstinence. Success may require several attempts and relapse is common. Complete abstinence may not be a realistic goal for many substance-misusing patients. Rather, increasing the proportion of days, weeks, and months free from mind-altering substances is an acceptable goal. (7) Work closely with a drug treatment program. (8) Define and agree on the roles and responsibilities of both the healthcare team and the patient. Establish a formal treatment contract that specifies the services to be provided to the patient, the caregiver’s expectations about the patient’s behavior, and periodic urine toxicology for substances, and delineate the consequences of behaviors that violates the contract. Such a contract should be agreeable to both parties, and not simply a contract of the physician’s expectations. (9) Set appropriate limits and respond consistently to behavior that violates those limits. These should be imposed in a professional manner that reflects the aim of enhancing patients’ well-being, and not in an atmosphere of blame or judgment. (10) Carefully evaluate pain syndromes and provide sufficient analgesia as medically indicated. (11) Always consider acute substance ingestion when evaluating behavior change and neurologic disease. Use urine toxicology testing to evaluate behavioral changes and to discourage illicit drug use by HIV-infected injection drug users during hospital stay. (12) Work consistently as a team. Do not make agreements about treatment decisions until the entire team has become involved. This will avoid ‘splitting’ behaviors that often unravel the fabric of a multidisciplinary team. (13) Consider integrating drug treatment into the HIV clinical care settings or HIV clinical care into a drug treatment setting (e.g., a methadone program). While there are no specific recommendations for accomplishing this goal, a number of key approaches have been described. These include complete integration where all clinicians are stakeholders in the treatment of both conditions, the integration of a specialized addiction specialist team or a hybrid model where both are implemented [9].

Commonly Used Drugs

Methamphetamine

Methamphetamine is a psychostimulant that is similar in chemical structure to amphetamine but has more profound effects on the central nervous system. It can be smoked, snorted, injected or administered rectally. Like cocaine, methamphetamine ingestion produces stimulation and similar feelings of euphoria; however, methamphetamine has a longer duration of action (6–8 h after a single dose). Tolerance develops rapidly and escalation of dose and frequency is required. As is the case with cocaine, methamphetamine use is associated with high-risk sexual behavior and subsequent HIV acquisition [10].

Alcohol

Although not illicit in most societies, the widespread use and medical and psychological importance of alcohol is associated with many adverse HIV effects. HIV-infected patients have a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption than the general population [11]. Alcohol use ranges from hazardous drinking (i.e. drinking at a level that could be hazardous to the individual’s health) to alcoholism. Alcohol use can result in ongoing risky sexual behaviors that can lead to the transmission of HIV [12, 13]. Alcohol use, in addition, can compromise cART by influencing both access and adherence to ARVs. In addition to HIV, alcohol has well-known negative effects upon the course of hepatitis C (HCV) treatment and HIV/HCV co-infected patients with hazardous drinking are of special concern [14]. As in all chemical dependencies, a comprehensive approach to the treatment of alcoholism integrates psychosocial treatment with pharmacologic treatments [5]. In the physiologically dependent patient, a structured withdrawal utilizing benzodiazepines or barbiturates is also necessary and typically occurs on an inpatient unit. Afterwards, a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments (e.g. 12 steps) should be utilized to maintain abstinence and can be prescribed by a primary care provider.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree