CHAPTER 10 Hematologic/immunologic disorders

General hematology assessment

Observation

• General: Chills, night sweats, altered mental status, confusion, restlessness, vertigo, visual changes

• Pain: Painful lymph nodes, painful joints, sore throat, sinusitis, headaches, abdominal pain

• Respiratory: Shortness of breath, exertional or chronic dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, orthopnea

• Cardiovascular: Activity intolerance, dizziness, palpitations, chest discomfort, painful legs, swollen legs

• Skin: Unusual bruising, itching, paleness, jaundice, grayness, ulcers, difficulty stopping bleeding from small cuts

• Musculoskeletal: Swollen and/or tender joints, sore muscles, weakness

• Gastrointestinal: Decreased appetite, feeling of fullness, hematemesis, melena, black stools, “coffee grounds” stomach secretions, weight loss, diarrhea, constipation

• Genitourinary: Cystitis, hematuria, heavy menstrual periods, enlarged groin lymph nodes

History

Patients at risk of hematologic or immunologic problems may report having the following disorders:

• Infections: Recent or recurrent; prior blood transfusion

• Allergies: Foods, beverages, medications, plants, animals, birds, fish, detergents, household cleaners, fragrances, seasonal patterns of respiratory symptoms

• Immunologic compromise: Cancer, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), liver or renal disorders; prior splenectomy, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, Hashimoto thyroiditis

• Healing: Prolonged bleeding or delayed healing with prior surgeries, including dental procedures

• Presence of foreign bodies: Prosthetic heart valves, inferior vena caval (IVC) filter, implantable defibrillators or other cardiac devices, vascular access devices

• Social history: Multiple sexual partners, excessive alcohol consumption, exposure to chemicals or radiation

• Medications, including over-the-counter medications: Aspirin, aspirin-containing drugs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); glucocorticoids/steroids, anticoagulants, platelet inhibitors (e.g., clopidogrel), chemotherapy, hormone therapy, oral contraceptives

Commonly Reviewed Components of the Complete Blood Count (CBC)

| Parameters | Significance | Normal Values |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hgb) | Protein in red blood cells containing iron which carries oxygen to tissues | 14–18 g/dL (males) 12–16 g/dL (female) |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | The percentage of red blood cells in the bloodstream. When the Hct is too low, those with anemia may experience fatigue. | 42%–52% (male) 37%–47% (female) |

| White blood cells (WBCs) | Cells of the immune system that protect the body from bacterial, fungal, and viral infections. Incidence of infection increases when WBCs are decreased. | 5000–10,000/mm3 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) | The number of neutrophils (mature white cells) in the blood. Neutrophils are a type of WBC that help fight infection. When ANC decreases, the patient is neutropenic and more prone to infection. Risk of infection increases when the ANC falls below 2000 and the greatest risk is below 500—a “right shift” on the WBC differential. | 2000/mm3 and above |

| WBC differential | Measures the percentage of each type of WBC in the total WBC count—a “left shift.” Indicates a large percentage of WBCs are neutrophils; indicates the bone marrow has been stimulated by a severe infection to produce neutrophils to fight the infection. Bands are immature neutrophils. “Right shift”: Indicates a small percentage of WBCs are neutrophils, putting the patient at higher risk for an infection; neutropenia. Eosinophilia: Increased eosinophils indicate an allergic reaction is present. Monocytes and lymphocytes: Act as “backup” to the neutrophils. Percentages increase during infection when oncology patients begin bone marrow recovery. If levels do not rise and then fall in a normal pattern, this can be a indication the patient has a poor prognosis for recovery. | Neutrophils: 50%–62% Bands: 3%–6% Monocytes: 3%–7% Basophils: 0%–1% Eosinophils: 0%–3% Lymphocytes: 25%–40% |

| Platelets (thrombocytes) | Cells that form the matrix on which blood clots are formed | 150,000–400,000/mm3 |

Anaphylactic shock

Pathophysiology

Anaphylaxis (anaphylactic shock) is a potentially life-threatening condition resulting from an exaggerated or hypersensitive response to an antigen or allergen. The classic presentation occurs in a sensitized person (i.e., someone who has been exposed previously to the same antigen), within 1 to 20 minutes of exposure to the antigenic substance, most often drugs, foods, insect stings or bites, antisera, and blood products. The hypersensitive response results in airway inflammation that causes obstruction and respiratory distress, which can lead to respiratory arrest, with a relative hypovolemia caused by massive vasodilation. Fluids shift from the vasculature into interstitial spaces, creating a false hypovolemia or vasogenic (vasodilated) shock, which progresses to end-organ dysfunction secondary to tissue hypoxia from poor perfusion.

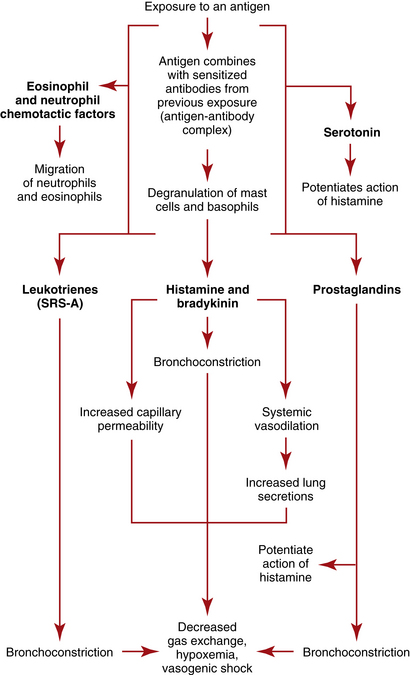

The antigen-antibody complexes activate production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which are termed slow-reacting substances of anaphylaxis (SRSA)—chemical mediators that produce systemic effects with potentially deleterious results, including profound shock. The leukotrienes produce severe bronchoconstriction and cause venule dilation and increased vascular permeability. The prostaglandins exaggerate bronchoconstriction and potentiate the effects of histamine on vascular permeability and pulmonary secretions. Kinins contribute to bronchoconstriction, vasodilation, and increased vascular permeability. Eosinophilic chemotactic factor of anaphylaxis (ECFA) is then released to attract eosinophils, which work to neutralize mediators such as histamine, but the amount of neutralization is ineffective in reversing the anaphylaxis. (See Figure 10-1 for a depiction of the pathophysiologic process of anaphylaxis.)

Assessment: anaphylactic shock

Goal of system assessment

• Assess the symptoms: Assess for ineffective breathing patterns, impaired gas exchange and airway obstruction, along with altered tissue perfusion related to vasodilation and third spaced intravascular fluids. Symptoms vary with means of antigen entry.

• Classify severity of reaction: Should be determined following initial assessment. Treatment must begin immediately; prior to when diagnostic test results are available. Shock may progress rapidly to circulatory collapse and cardiopulmonary arrest if improperly managed.

• Evaluate effectiveness of prior treatments: Determine patient’s prior treatment regime if asthmatic; classify which “step” of treatment has been needed to control symptoms; patient may need to move to the next step of treatment to maintain control (see Acute Asthma Exacerbation, p 354).

Vital signs

• Pulse oximetry: Oxygen saturation is decreased from patient’s baseline value.

• Tachycardia (heart rate [HR] greater than 140 beats/min [bpm]) and tachypnea (respiratory rate [RR] greater than 40 breaths/min)

• Hypotension may be present; hypotension is exacerbated by underlying vasodilation coupled with increased capillary permeability prompting third spacing of intravascular fluids.

Observation (see table 10-1)

• Red to purple discoloration of face and body; “extreme flushing” with swelling of lips, eyelids, and face due to angioedema

• Tears coming from eyes with strained facial expression

• Severe reactions render patients unable to speak due to breathlessness

• Use of accessory muscles; fatigued, with or without diaphoresis

• Chest expansion may be decreased or restricted.

• Altered level of consciousness (LOC) (confusion, disorientation, agitation)

• Agitation is more commonly associated with hypoxemia while somnolence is associated with hypercarbia (elevated carbon dioxide level).

• General early indicators (occurring within seconds to minutes) include uneasiness, lightheadedness, tingling feeling, flushing, and pruritus.

• General late indicators (occurring within minutes) include rapid progression of urticaria involving large areas of skin; angioedema (tissue swelling; more commonly the eyes, lips, tongue, hands, feet, and genitalia); cough, hoarseness, dyspnea, and respiratory distress; lightheadedness or syncope; and abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting

• Ingestion of antigen: Cramping, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting may precede systemic shock symptoms.

• Inhalation of antigen: Cough, hoarseness, wheezing, dyspnea

• Allergic reaction: Edema, urticaria, itching at the site of a bee sting or drug injection

Table 10-1 SYSTEMIC EFFECTS OF ANAPHYLAXIS

| System | Effects | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Neurologic | Apprehension; headache; confusion; decreased LOC progressing to coma | Vasodilation; hypoperfusion; cerebral hypoxia or cerebral edema occurring with interstitial fluid shifts |

| Respiratory | Dyspnea progressing to air hunger and complete respiratory obstruction; hoarseness; noisy breathing; high-pitched, “barking” cough; wheezes; crackles; rhonchi; decreasing breath sounds; pulmonary edema (some patients) | Laryngeal edema; bronchoconstriction; increased pulmonary secretions |

| Cardiovascular | Decreased BP leading to profound hypotension; increased HR; decreased amplitude of peripheral pulses; palpitations and dysrhythmias (atrial tachycardias, premature atrial beats, atrial fibrillation, premature ventricular beats progressing to ventricular tachycardia, or ventricular fibrillation); lymphadenopathy | Increased vascular permeability; systemic vasodilation; decreased cardiac output with decreased circulating volume; reflex increase in HR; vasogenic shock |

| Renal | Increased or decreased urine output; incontinence | Decreased renal perfusion; smooth muscle contraction of urinary tract |

| Gastrointestinal | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramping | Smooth muscle contraction of GI tract; increased mucus secretion |

| Cutaneous | Urticaria; angioedema (hands, lips, face, feet, genitalia); itching; erythema; flushing; cyanosis | Histamine-induced disruption of cutaneous vasculature; vasodilation, increased capillary permeability; decreased oxygen saturation |

BP, Blood pressure; HR, heart rate; GI, gastrointestinal; LOC, level of consciousness.

Percussion

Diagnostic Tests for Anaphylaxis

| The diagnosis of anaphylaxis is based on presenting signs and symptoms. Treatment should be initiated before laboratory results are available. | ||

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

| Arterial blood gas analysis (ABG) | Assess for abnormal gas exchange or compensation for metabolic derangements. Initially, PaO2 is normal and then decreases as the ventilation-perfusion mismatch becomes more severe. | pH changes: Acidosis may reflect respiratory failure; alkalosis may reflect tachypnea; Carbon dioxide: Elevated CO2 reflects respiratory failure; decreased CO2 reflects tachypnea; rising PCO2 is an ominous sign, since it signals severe hypoventilation which can lead to respiratory arrest. Hypoxemia: PaO2 <80 mm Hg Oxygen saturation: SaO2 <92% |

| Complete blood count (CBC) with WBC differential | WBC differential evaluates the strength of the immune system’s response to the trigger of response | Eosinophils: Increased in patients not receiving corticosteroids; indicative of magnitude of inflammatory response Hematocrit (Hct): May be increased from hypovolemia and hemoconcentration |

| Tryptase level | Assesses for this chemical mediator released by mast cells following anaphylaxis | Increases within 1 hour following anaphylaxis and remains elevated for 4–6 hours |

| IgE levels | Used to confirm origin of the reaction is an allergic response | Levels are elevated if allergic response is present. |

| 12-Lead electrocardiogram (ECG) | To detect dysrhythmias reflective of myocardial ischemia | Ischemic changes (ST depression) may be present as shock progresses. |

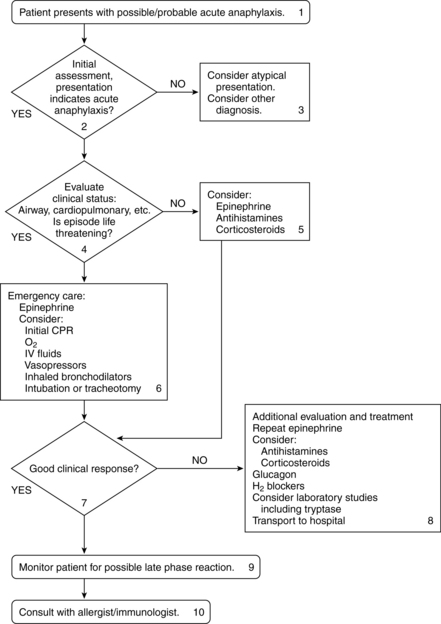

Collaborative management (see figure 10-2)

Figure 10-2 Algorithm for the treatment of acute anaphylaxis.

(From Nicklas RA, et al: The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 101(6 Pt 2):S465–S528, 1998.)

Care priorities

2. Provide supplemental oxygen:

Administered to support ventilation and aerobic metabolism. Amount and method of oxygen administration are guided by arterial blood gas (ABG) results. Often initiated at 6 L/min via nasal cannula or oxygen mask.

3. Manage vasodilation and increased capillary permeability

• Standard adult dose: 0.2 to 0.5 mg (0.2 to 0.5 ml of a 1:1000 solution) given intramuscularly (IM) or subcutaneously (SC)

• Alternate initial dose: 0.1 mg (0.1 ml of a 1:1000 solution) may be administered.

• Repeat dosage: may be repeated every 10 to 15 minutes as needed

• IV dosage: preferred if patient is in shock and/or has severe airway obstruction: Initial dose of 0.1 to 0.25 mg (1.0 to 2.5 ml of 1:10,000 solution) over 5 to 10 minutes. The dose may be increased to 0.3 to 0.5 mg. Repeat every 5 to 15 minutes as needed.

• IV infusion: after initial dose, an IV drip of epinephrine 1.0 mg in 250 ml D5W may be infused at 1 mcg/min and increased to 4 mcg/min (or more) as needed to achieve desired response.

• Endotracheal (ET) tube: 1.0 to 2.5 ml of 1:10,000 solution (1 mg epinephrine in 10-ml solution) into ET tube, followed by use of manual resuscitation (Ambu) bag. May repeat if needed.

Used if fluid replacement does not increase blood pressure (BP). Drugs are titrated for the desired response (see Appendix 6). Usual dosages are as follows:

• Dopamine hydrochloride: Effects are dose dependent. Increases cardiac contractility at 5 to 10 mcg/kg/min and systemic vascular resistance at 10 to 20 mcg/kg/min. Consider switching to norepinephrine if dose exceeds 20 mcg/kg/min.

• Norepinephrine: Initial dosage is 2 to 8 mcg/min and can be increased to achieve the necessary BP.

• Phenylephrine: Usual dosage is 40 to 60 mcg/min. Doses exceeding 200 mcg/min have been used.

f. Inhaled bronchodilators (e.g., albuterol):

May be given for continued bronchospasm (see Acute Asthma Exacerbation, p. 354).

CARE PLANS FOR ANAPHYLAXIS AND ANAPHYLACTIC SHOCK

1. Assess continuously for obstructed airway and increased respiratory effort: Note increased pulmonary secretions, cough, expiratory wheezing, SOB, and dyspnea. Suction as needed. Caution: An oral airway provides airway support only as far as the posterior pharynx. If laryngeal edema is present, the oral airway cannot relieve symptoms because the obstruction is below the oral airway. If ET intubation is attempted and is not possible due to laryngeal edema, prepare for tracheostomy or cricothyroidotomy.

2. Monitor for decreased breath sounds or changes in wheezing at frequent intervals: Absent breath sounds in a distressed patient may indicate impending respiratory arrest. Identify patient requiring actual/potential airway insertion. Consult physician and prepare for ET intubation if lingual edema is present and/or respiratory distress continues.

3. Position patient for comfort and to promote optimal gas exchange: High Fowler’s position, with the patient leaning forward and elbows propped on the over-the-bed table to promote maximal chest excursion, may reduce use of accessory muscles and diaphoresis due to work of breathing. May not be possible with severe hypotension, as further decrease in BP may result.

1. Monitor for signs of increasing hypoxia at frequent intervals: Restlessness, agitation, and personality changes are indicative of severe reaction. Cyanosis of the lips (central) and nail beds (peripheral) are late indicators of hypoxia, but may be difficult to see with severe angioedema.

2. Monitor for signs of hypercapnia at frequent intervals: Confusion, listlessness, and somnolence are indicative of respiratory failure.

3. Provide medications to abate allergic response: Administer epinephrine and IV and inhaled bronchodilators as appropriate to attain control of deterioration.

Respiratory Status: Ventilation

1. Monitor FIO2 to ensure that oxygen is within prescribed concentrations. If patient does not retain carbon dioxide, 100% nonrebreather mask may be used to provide maximal oxygen support. If the patient retains CO2 and is unrelieved by positioning, lower-dose oxygen, bronchodilators and steroids, intubation, and mechanical ventilation may be necessary sooner than in patients who are able to receive higher doses of oxygen by mask.

2. Monitor ABGs when continuous pulse oximetry values or patient assessment reflects progressive hypoxemia or development of hypercapnia. Monitor and report ABG values with increasing PaCO2 (greater than 50 mm Hg) or decreasing PaO2 (less than 60 mm Hg) indicative of impending respiratory failure.

3. Administer antihistamines as prescribed.

4. Administer glucocorticoids as prescribed.

5. Position patient to alleviate dyspnea (assist patient to sitting position if BP is stable).

6. Stay with patient to promote safety and reduce fear. Use calm, reassuring approach.

![]() Respiratory Monitoring; Emotional Support; Medication Administration, Medication Management

Respiratory Monitoring; Emotional Support; Medication Administration, Medication Management

Circulation Status; Tissue Perfusion: Cardiac; Vital Signs

1. Assess for physical and hemodynamic indicators of decreased cardiac output:

2. Monitor for dysrhythmias, such as atrial tachycardias, PVCs, ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation, which may signal hypoxemia or occur as side effects of drugs such as aminophylline or epinephrine.

4. Administer epinephrine as prescribed. Observe for therapeutic effects as evidenced by increased SVR, increased CO/CI, increased ScVO2, increased arterial BP and MAP, stronger peripheral pulses, warming of extremities, and increased urine output.

5. Administer fluid replacement therapy as prescribed, using a large-bore IV catheter. Colloids and crystalloids may be given together.

6. Prepare for possible vasopressor infusion if hypotension persists after fluid resuscitation and epinephrine administration.

Altered tissue perfusion: peripheral, renal, and cerebral

related to hypovolemia secondary to fluid shift from the vascular space to the interstitial space

Tissue Perfusion: Abdominal Organs, Tissue Perfusion: Peripheral; Tissue Perfusion: Cerebral

1. ![]() Assess peripheral pulses. Report decreased amplitude of pulses.

Assess peripheral pulses. Report decreased amplitude of pulses.

2. Assess capillary refill. Delayed capillary refill (greater than 2 seconds) is likely with edema and decreased vascular volume.

3. Assess degree of peripheral edema.

4. Assess color and warmth of extremities. Report presence of coolness and pallor.

5. Monitor BP at frequent intervals. Be alert for indicators of hypotension such as BP readings greater than 20 mm Hg below patient’s normal pressure, dizziness, restlessness, altered mentation, and decreased urinary output.

6. Monitor urine output hourly. Continuous CO monitoring using a noninvasive system or a pulmonary artery catheter may be needed to guide fluid resuscitation.

7. Observe for indicators of decreased cerebral perfusion such as anxiety, restlessness, confusion, and decreased LOC.

HIGH ALERT!

Changes in LOC may signal either decreased cerebral perfusion (tissue hypoxia) or increasing intracranial pressure (IICP) caused by interstitial swelling from capillary permeability.

8. Administer fluid and pharmacologic agents as prescribed (see previous nursing diagnosis).

![]() Hemodynamic Regulation; Anaphylaxis Management; Medication Administration, Medication Management

Hemodynamic Regulation; Anaphylaxis Management; Medication Administration, Medication Management

related to urticaria and angioedema secondary to allergic response

Tissue Integrity: Skin and Mucous Membranes

1. Assess patient for urticaria (hives) and itching of hands, feet, neck, and genitalia.

2. Administer antihistamines as prescribed to relieve itching.

3. Discourage patient from scratching the skin. If unavoidable, teach patient to use pads of fingertips rather than nails.

4. Apply cool washcloths or covered ice as a soothing measure to irritated and edematous areas.

![]() Environmental Management: Comfort; Medication Administration

Environmental Management: Comfort; Medication Administration

Deficient knowledge illness care: severe hypersensitivity reaction, its causes, and its symptoms

related to no prior exposure or incomplete understanding

1. Provide information about the antigenic agent that caused the anaphylaxis, including ways to avoid it in the future.

2. Explain need for wearing a medical-alert identification tag or bracelet to identify the allergy.

3. Give information about anaphylaxis emergency treatment kits. Teach patient self-administration technique and the importance of prompt treatment.

4. Stress the importance of seeking treatment immediately if symptoms of allergy occur, including flushing, warmth, itching, anxiety, and hives.

5. Explain the importance of identifying and checking all over-the-counter (OTC) medications for the presence of potential allergens.

![]() Health Education; Risk Identification; Teaching: Prescribed Medication

Health Education; Risk Identification; Teaching: Prescribed Medication

Profound anemia and hemolytic crisis

Pathophysiology

Anemia

Anemia reflects a reduction in total body hemoglobin (Hgb) concentration and is common in critically ill patients. By the third day in an intensive care unit (ICU), 95% of patients have reduced Hgb concentrations. As the Hgb decreases, the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood is reduced, resulting in tissue hypoxia unless compensatory mechanisms are adequate to assist the body with oxygen delivery. Anemia may be classified under one of three functional classes after initial evaluation of the CBC and reticulocyte index. (See Table 10-2 for functional classification.)

Table 10-2 FUNCTIONAL CLASSES OF ANEMIA WITH EXAMPLES

| Blood Loss/Hemolysis | Decreased RBC Production | Maturation Disorders |

| Autoimmune diseases Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia Purpura (TTP), Goodpasture’s Syndrome, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), Wegener’s Granulomatosis | Damaged bone marrow: malignancy, lead poisoning, aplastic/hypoplastic anemia, chemotherapy, viruses | Abnormal RBC cytoplasm Phenylketonuria (PKU), G6PD |

| Abnormal hemoglobin Sickle cell disease, Hgb S, C D, E | Iron deficiency: malignancy, autoimmune disorders | Abnormal RBC nucleus |

| Abnormal RBC membranes Spherocytosis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, paroxysmal nocturnal hematuria | Erythropoietin deficiency: renal failure, malaria, thalassemias | Iron deficiency: dietary, chronic alcoholism |

| Bleeding/hemorrhage Physical trauma to blood (bypass, balloon, valves), antibodies (drug-induced antibodies), endotoxins (malaria, clostridia), GI bleed, trauma, rupture, excess menstruation | Inflammation/infection: chronic inflammatory disease; critical illness | |

| Excessive phlebotomies: lab sampling | Metabolic disturbance: pernicious anemia, hypothyroidism, megaloblastic anemia |

Assessment

Hemolytic crisis

Diagnostic Tests for Anemias and Hemolytic Crisis

| Test | Purpose | Abnormal Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Red blood cell count (RBCs) | Enumeration of the red cells found in each cubic millimeter of blood | Reduced; in hemolytic crisis, an increased number of premature RBCs (nucleated RBCs) will be present. |

| Hemoglobin (Hgb) | Hemoglobin content of RBCs | Decreased |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | Percentage of RBCs in relation to total blood volume | Decreased |

| Reticulocyte count, reticulocyte index, corrected reticulocyte | RBC precursors; measures how fast RBCs are produced in the bone marrow | Elevated: because of increased bone marrow production of RBCs due to blood loss or RBC destruction; also a sign of marrow recovery after chemotherapy. |

| Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (subcategory of red cell indices) Macrocytic: MCV >100 mcg3 Microcytic: MCV <80 mcg3 Normocytic: MCV 80–100 mcg3 | Morphologic classification of RBCs: average size of individual RBCs. Obtained by dividing HCT by total RBC count | Low in microcytic anemia; high in macrocytic anemia |

| Sickle cell test | Indicative of sickle cell anemia (trait, disease) | Presence of Hemoglobin S (Hgb S) |

| Hemoglobin (Hgb) electrophoresis | Screens for abnormal hemoglobins often present in hemolytic anemias Many hemoglobinopathies are interrelated. Disease expression is based on the degree of genetic abnormalities. Various combinations of abnormal hemoglobins are possible | Hemoglobins A1, A2, and F: Normal Hgb Hemoglobin C: Generally benign; May cause joint pain, splenomegaly and gallstones; may protect against malaria Hemoglobins D and E: Rarely occur “singly”; sometimes present with sickle cell disease or thalassemias Hemoglobin H: Causes premature destruction of RBCs and abnormal binding of O2 to RBCs; causes alpha thallasemia Hemoglobin S: Most common abnormal hemoglobin, occurring in 10% of the African American population; causes sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), sedimentation rate or Biernacki reaction | Rate at which RBCs precipitate in a period of 1 hour: nonspecific measure of inflammation | Elevated in hemolytic anemia; decreased in sickle cell anemia, polycythemia and congestive heart failure |

| C3 proactivator | Proactivator of complement 3 in the alternate pathway of complement activation | Increased in hemolytic anemia |

| Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) | Measures the blood’s capacity to bind iron with transferrin; also indirect test of liver function (rarely used for that) TIBC is typically measured along with serum iron to evaluate people suspected of having either iron deficiency or iron overload. | Normal or reduced, depending on the type of anemia |

| Ferritin | Iron stores: with damage to organs that contain ferritin (especially the liver, spleen, and bone marrow), ferritin levels can become elevated even though the total amount of iron in the body is normal. | Reduced with iron deficiency anemia; normal or elevated with anemia of critical illness; elevated with hemachromatosis |

| Transferrin | Used to determine the cause of anemia, to examine iron metabolism (for example, in iron deficiency anemia) and to determine the iron-carrying capacity of the blood. | Reduced with anemia of chronic inflammation, anemia of critical illness. |

| Transferrin saturation | The iron concentration divided by TIBC—a more useful indicator of iron status than iron or TIBC alone. | Reduced with anemia of chronic inflammation, anemia of critical illness. |

| Folate; folic acid | Measures folic acid in the blood | Reduced with nutritional deficiency leading to megaloblastic anemia. |

| Erythropoietin (EPO, EP) | Measures the amount of a hormone called erythropoietin (EPO) in blood; acts on stem cells in the bone marrow to increase the production of red blood cells; made by cells in the kidney, which release the hormone when oxygen levels are low. | Reduced with renal disease and normal in those who are critically ill who should have an elevated level if anemia of any cause is present. Reticulocyte response to EP has been shown to be reduced in many critically ill patients with elevated EP levels. |

| Vitamin B12 | Measures the amount of vitamin B12 in the blood; used with folic acid test, because a lack of either can cause megaloblastic anemia. | Reduced with pernicious or megaloblastic anemia. |

| Unconjugated bilirubin: free bilirubin, indirect bilirubin | Measures bilirubin that has not been conjugated in the liver. It gives an indirect reaction to the Van Den Bergh test. | Elevated in hemolytic anemia due to liver’s inability to process increasing bilirubin released during hemolysis. |

| Serum lactic dehydrogenase isoenzymes (LDH1 and LDH2 ) | General indicator of the existence and severity of acute or chronic tissue damage and, sometimes, as a monitor of progressive conditions; monitor damage caused by muscle trauma or injury and to help identify hemolytic anemia | Elevated in hemolytic anemia because of their release when an RBC is destroyed. |

| Haptoglobin level | Used to detect and evaluate hemolytic anemia; not to diagnose cause of the hemolysis. Haptoglobin levels should be drawn prior to transfusion. | Decreased in hemolytic anemia due to increased binding of haptoglobin, which facilitates removal of increased Hgb from blood. |

| Peripheral blood smear | Microscopic examination of cells from drop of blood; investigates hematologic problems or parasites such as malaria and filaria | May reveal abnormally shaped RBCs, such as spherocytes. RBC hyperplasia (abnormal number) is present in nearly all cases of chronic hemolysis with intact bone marrow. |

| Bone marrow aspiration | Evaluates bone marrow status; diagnose blood disorders and determine if cancer or infection has spread to the bone marrow. | May reveal abnormal size, shape, or amounts of RBCs, WBCs or platelets |

| Coombs test: Direct antiglobulin test; Indirect antiglobulin test | Detects antibodies that may bind to RBCs and cause premature RBC destruction | Positive in antibody-mediated immunologic hemolysis. |

| Immunoglobulin levels | Measures the level of immunoglobulins, also known as antibodies, in the blood. | Elevated: autoimmune disorders, sickle cell; lower in immunocompromised states. |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) levels | Measures G6PD—enzyme levels are normal in newly produced cells but fall as RBCs age and only deficient cells are destroyed. | Decreased in G6PD deficiency, hemolysis Elevated: MI, liver failure, chronic blood loss, hyperthyroidism |

| Radiologic examinations | X-rays and bone scans Liver/spleen scans | Decreased density, aseptic necrosis of bones Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lesions |