CHAPTER 8 Hematologic Disorders

Section One Disorders of the Red Blood Cells

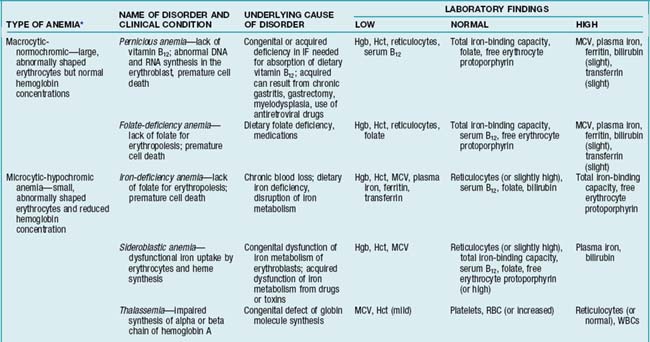

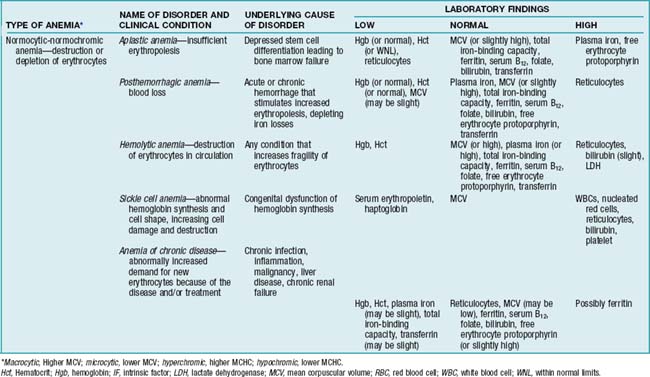

Anemias can be classified in two ways: (1) those involving diminished production or accelerated loss of RBCs (etiology) or (2) those involving cell size (morphology). For details, see TABLES 8-1 and 8-2. Three common types of anemias are discussed in this section: anemia of chronic disease, hemolytic and sickle cell anemia, and hypoplastic (aplastic) anemia.

TABLE 8-1 ETIOLOGIC (PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC) CLASSIFICATIONS OF ANEMIA

| TYPE | CAUSE | DISEASES |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased or defective production of erythrocytes | Altered hemoglobin synthesis | Iron deficiency |

| Thalassemia | ||

| Anemia of chronic inflammation or disease | ||

| Altered DNA synthesis from deficient nutrients | Pernicious anemia (decreased vitamin B12, folate) | |

| Stem cell dysfunction | Aplastic anemia, myeloproliferative leukemia or dysplasia | |

| Bone marrow infiltration | Carcinoma, lymphoma, multiple myeloma | |

| Autoimmune disease or idiopathic | Pure red cell aplasia | |

| Increased erythrocyte destruction | Blood loss | Acute (hemorrhage, trauma) |

| Chronic (gastrointestinal bleeding, menorrhagia) | ||

| Hemolysis (intrinsic) | Hereditary spherocytosis, sickle cell trait or disease, pyruvate kinase deficiency, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency | |

| Hemolysis (extrinsic) | Warm or cold antibody disease, infection (malarial, clostridial), erythrocyte trauma (hemolytic uremic syndrome, TTP, mechanical cardiac valve, paravalvular leak), splenic sequestration, burns |

TTP, Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Anemia of Chronic Disease

Anemia of Chronic Disease

Diagnostic Tests

Ferritin

Normal or increased. However, if it is less than 30 mcg/L, there is a coexisting iron deficiency.

Peripheral blood smear to examine RBC indices

Normocytic and normochromic erythrocytes (normal or slightly low mean corpuscular volume [MCV]).

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions

Activity intolerance

Nursing Interventions

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Include verbal and written information about the following:

Hemolytic and Sickle Cell Anemia

Hemolytic and Sickle Cell Anemia

Overview/Pathophysiology

Hemolytic anemia is characterized by abnormal or premature destruction of RBCs. Hemolysis can occur because of intrinsic or extrinsic factors (Table 8-1), for example, from a foreign antigen (e.g., from a transfusion reaction) or an autoimmune reaction in which the hemolytic agent is intrinsic to the patient’s body. Other possible causes include exposure to radiation and ingestion of certain medications (e.g., sulfisoxazole, phenytoin, methyldopa). Acquired hemolytic anemia is usually the result of an abnormal immune response that causes premature destruction of RBCs.

Assessment

Signs and symptoms/physical findings

Acute indicators (hemolytic crisis)

Fever; headache; visual blurring or temporary blindness; severe abdominal pain; vomiting; splenomegaly; hepatomegaly; back, lower leg, and joint pain; priapism; palpitations; shortness of breath (because of pulmonary sequestration, anemia, infection); aplastic crisis (resulting from transient marrow suppression by viruses); chills; lymphadenopathy; decreased urinary output; and stroke. Peripheral nerve damage can result in paralysis or paresthesias. Occasionally a low-grade fever may occur 1-2 days after a crisis event. Attacks last a few hours to a few days and resolve spontaneously.

Collaborative Management

Erythrocytapheresis (RBC exchange or partial exchange)

A procedure that removes abnormal RBCs and infuses healthy RBCs with or without normal saline to correct the anemia. It is used for younger patients with a history of stroke or for individuals with pulmonary or cardiac disease.

Stem cell transplant from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched donor following high-dose chemotherapy

Nursing Diagnoses and Interventions

Chronic pain

related to joint hemolysis secondary to hemolytic crisis or sickle cell disease

Nursing Interventions

Ineffective peripheral and cardiopulmonary tissue perfusion

related to inflammatory process and occlusion of blood vessels with RBCs

Desired outcome

Following treatment, patient has adequate peripheral and cardiopulmonary perfusion, as evidenced by SBP 10 mm Hg or less lower than baseline SBP, peripheral pulses 2+ or more on a 0-4+ scale, heart rate (HR) 100 beats per minute (bpm) or less, respiratory rate (RR) 12-20 breaths/min with normal depth and pattern (eupnea), and normal skin color.

Nursing Interventions

Nursing Interventions

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Patient-Family Teaching and Discharge Planning

Include verbal and written information about the following: