OVERVIEW AND ASSESSMENT

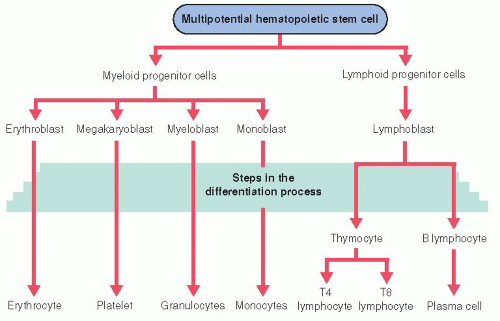

Blood, the body fluid circulating through the heart, arteries, capillaries, and veins, consists of plasma and cellular components. The average male adult has about 5.5 L of blood, the average female 4.5 L. Plasma, the fluid portion, accounts for 55% of the blood volume and is composed of 92% water, 7% protein, and 1% inorganic salts; nonprotein organic substances such as urea; dissolved gases; hormones; and enzymes. Plasma proteins include albumin, fibrinogen, and globulins. Cellular components include erythrocytes (red blood cells [RBCs]), leukocytes and lymphocytes (white blood cells [WBCs]), and platelets. These cells are derived from pluripotent stem cells in the bone marrow, a process known as hematopoiesis (see

Figure 26-1). Under normal conditions, only mature cells are found in circulating blood. The cellular components of blood account for 45% of the blood volume.

Characteristics of Cellular Components

Blood has multiple functions that are carried out by plasma or the cellular components (see

Table 26-1, page 973).

Erythrocytes (RBCs)

Enucleated, biconcave disc.

Approximately 5 million erythrocytes per cubic millimeter of blood.

Cell contents consist primarily of hemoglobin, essential for oxygen transport. Whole blood contains 14 to 15 g of hemoglobin per 100 mL of blood.

Circulate about 115 to 130 days before elimination by reticuloendothelial system, primarily in spleen and liver.

Leukocytes (WBCs)

Approximately 5,000 to 10,000 leukocytes (WBCs) per cubic millimeter of blood.

Classified as granulocytes or mononuclear leukocytes.

Granulocytes account for about 70% of all WBCs; have abundant granules in cytoplasm; include neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils.

Mononuclear leukocytes have single-lobed nucleus and granule-free cytoplasm; include monocytes and lymphocytes.

Platelets (Thrombocytes)

Approximately 150,000 to 450,000 platelets per cubic millimeter of blood.

Small particles without nuclei arise as a result of budding from giant cells (megakaryocytes) in bone marrow.

Primary function is to control bleeding through hemostasis.

Subjective and Objective Data

The patient who presents with a hematologic disorder may have a disruption of the hematologic, immune, or coagulation system, producing a diverse array of symptoms and physical examination findings. Patients commonly present with vague complaints of fatigue, frequent infections, swollen glands, and bleeding tendencies. Characterize these complaints and obtain a review of systems, concentrating on the neurologic, respiratory, cardiovascular, GI, genitourinary (GU), and integumentary systems to look for more clues of hematologic dysfunction. Perform a systematic physical examination, paying careful attention to the cardiovascular, respiratory, and integumentary systems.

Review of Systems

Skin and mucous membranes: Any bruises, infections, drainage, or bleeding from wound sites?

Neurologic: Any dizziness, tingling or numbness (paresthesia), headache, forgetfulness or confusion, difficulty walking (disturbance in gait), tiredness (fatigue), weakness?

Respiratory: Experiencing shortness of breath, especially on exertion?

Cardiovascular: Chest pain or feelings of funny heartbeats (palpitations)?

GI: Any bleeding from gums, abdominal pain, black stools, or blood-streaked vomit (emesis)? Any mouth sores, rectal pain, or diarrhea?

GU: Excessive menstrual flow? Any blood in urine or discomfort on urination?

Key History Questions

What are your present medications? Do you take over-thecounter (OTC) medications, vitamins, herbals, or nutritional supplements? What else have you taken in the past several months?

What medical problems have you had in the past? Any surgeries? Ask specifically about partial or total gastrectomy, splenic injury or splenectomy, tendency to bleed (eg, with dental procedures), infectious diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, cancer.

What is your occupation? Ask about exposure to substances such as benzene, pesticides, and ionizing radiation.

Do you have a family history of hematologic or malignant disorder?

Determine the social history and lifestyle. Do you use illicit drugs or alcohol? What is your pattern of sexual activity?

Key Examination Findings

Dyspnea; shiny smooth tongue; ataxia; pallor of conjunctivae, nail beds, lips, and oral mucosa—suggest anemia.

Decreased blood pressure (BP), tachycardia, possibly altered level of consciousness (LOC)—suggest anemia or altered blood clotting.

Hematuria, tarry stools, petechiae, bleeding sites—suggest altered clotting.

Fever; tachycardia; abnormal breath sounds; delirium; oral lesions; erythema, swelling, tenderness, and drainage of the skin—suggest infection.

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies routinely done for patients with hematologic disorders include complete blood count (CBC), blood smear, and iron profile. Blood samples for these tests are most accurate when obtained by venipuncture (see

Procedure Guidelines 26-1, pages 974 to 975).

Complete Blood Count

Description

Generally includes absolute numbers or percentages of erythrocytes, leukocytes, platelets, hemoglobin, and hematocrit in blood sample.

Erythrocyte (RBC) indices—can be done to provide information on the size, hemoglobin concentration, and hemoglobin weight of an average RBC; aids in diagnosis and classification of anemias.

Leukocyte (WBC) differential—can be done to determine the percentage of each type of granulocyte (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils) and nongranulocytes (lymphocytes and monocytes).

Absolute value of each is determined by multiplying the percentage by the total number of WBCs.

Used to evaluate infection or potential for infection and identify various types of leukemia.

Nursing and Patient Care Considerations

Blood sample can be drawn at any time without fasting or patient preparation.

Blood Smear

Description

Blood sample prepared for microscopic viewing using appropriate stains, allowing visual analysis of numbers and characteristics of cells; can identify abnormal cells of certain anemias, leukemias, and other disorders that affect the bloodstream.

Nursing and Patient Care Considerations

Can be done from blood sample drawn for CBC; no additional sample or patient preparation is necessary.

Iron Profile

Description

Test completed on blood sample that generally includes levels of serum ferritin, iron, total iron-binding capacity, folate, vitamin B12; used to determine type and severity of anemia.

Nursing and Patient Care Considerations

Recent administration of chloramphenicol, hormonal contraceptives, iron supplements, and corticotropin may affect results of serum iron and iron-binding capacity. No patient preparation needed.

Other Diagnostic Procedures

Bone Marrow Aspiration

Description

Aspiration of bone marrow from the iliac crest or (rarely) sternum to obtain specimen to examine microscopically and to perform a biopsy (see

Procedure Guidelines 26-2, page 976).

Purposes include diagnosis of hematologic disorders; monitoring of course of illness and response to treatment; diagnosis of other disorders, such as primary and metastatic tumors, infectious diseases, and certain granulomas; and isolation of bacteria and other pathogens by culture.

Nursing and Patient Care Considerations

Give medication for pain and anxiety before or after the procedure, as ordered. A bone marrow aspiration with biopsy is more painful and may require use of mild to moderate sedation with appropriate monitoring.

Watch for bleeding and hematoma formation after procedure.

Lymph Node Biopsy

Description

Surgical excision or needle aspiration usually of a superficial lymph node in the cervical, supraclavicular, axillary, or inguinal region.

Performed to determine the cause of lymph node enlargement, to distinguish between benign and malignant lymph node tumors, and to stage metastatic carcinoma.

Nursing and Patient Care Considerations

GENERAL PROCEDURES AND TREATMENT MODALITIES

Splenectomy

The spleen is a fist-size organ located in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen. It includes a central “white pulp” where storage and some proliferation of lymphocytes and other leukocytes occurs and a peripheral “red pulp” involved in fetal erythropoiesis, and later in erythrocyte destruction and the conversion of hemoglobin to bilirubin. It may be surgically removed because of trauma or to treat certain hemolytic or malignant disorders with accompanying splenomegaly. A laparoscopic technique, usually with a lateral approach, is preferred to remove a normal to slightly enlarged spleen in benign conditions, such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic anemia, or sickle cell disease. Compared to open surgery, laparoscopic splenectomies have a shortened hospital stay, decreased postoperative pain, and decreased risk of wound complications such as adhesions and infections.

Preoperative Management

For general aspects of preoperative nursing management, see

Chapter 7.

Stabilization of preexisting condition:

For trauma: volume replacement with intravenous (IV) fluids, evacuation of stomach contents via nasogastric tube to prevent aspiration, urinary catheterization to monitor urine output, assessment for pneumothorax or hemothorax and possible chest tube placement.

For hemolytic or malignant disorder with accompanying thrombocytopenia: coagulation studies, administration of coagulation factors (eg, vitamin K, fresh-frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate), platelet and red cell transfusions.

Preoperative pulmonary evaluation and teaching.

For patient undergoing elective splenectomy, vaccination against pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenzae type B, and meningococcus are given at least 2 weeks before surgery.

Postoperative Management

For general aspects of postoperative nursing management, see

Chapter 7.

Prevention of respiratory complications: hypoventilation and limited diaphragmatic movement, atelectasis of left lower lobe, pneumonia, left pleural effusion.

Monitoring for hemorrhage.

Pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis, begun in operating room or if patient is at increased bleeding risk, as soon as bleeding risk subsides.

Administration of opioids for pain and observance for adverse effects.

Monitoring for fever.

Postsplenectomy fever—mild, transient fever is expected.

Persistent fever may indicate subphrenic abscess or hematoma.

Monitoring daily platelet count: thrombocytosis (elevation of platelet count) may appear a few days after splenectomy and may persist during first 2 weeks.

Potential Complications

Pancreatitis and fistula formation: tail of pancreas is anatomically close to splenic hilum.

Hemorrhage.

Atelectasis and pneumonia.

Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI)—increased risk of developing a life-threatening bacterial infection with encapsulated organisms, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, or H. influenzae type b. The incidence of OPSI is 0.23% to 0.42% per year with a lifetime risk of 5%. An OPSI is a medical emergency and requires immediate IV antibiotics in an intensive care setting. IV immunoglobulins are also used.

Nursing Diagnoses

Ineffective Breathing Pattern related to pain and guarding of surgical incision.

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to hemorrhage caused by surgery of highly vascular organ.

Risk for Injury (thromboembolism) related to thrombocytosis.

Risk for Infection related to surgical incision and removal of the spleen.

Acute Pain related to surgical incision.

Nursing Interventions

Maintaining Effective Breathing

Assess breath sounds and report absent, diminished, or adventitious sounds.

Assist with aggressive chest physiotherapy and incentive spirometry.

Encourage early and progressive mobilization.

Monitoring for Hemorrhage

Monitor vital signs frequently and as condition warrants.

Measure abdominal girth and report abdominal distention.

Assess for pain and report increasing pain.

Prepare patient for surgical re-exploration if bleeding is suspected.

Avoiding Thromboembolic Complications

Monitor platelet count daily, report abnormal result promptly.

Administer DVT prophylaxis, as ordered.

Assess for possible thromboembolism.

Assess skin color, temperature, and pulses.

Advise patient to report chest pain, shortness of breath, pain, or weakness.

Report signs of thromboembolism immediately.

Preventing Infection

Assess surgical incision daily or if increased pain, fever, or foul smell.

Maintain meticulous handwashing and change dressings using sterile technique.

Teach patient to report signs of infection (fever, malaise) immediately.

Educate patient and family regarding OPSI, including plan for postsplenectomy immunizations, recognition of symptoms, use of prophylactic and standby antibiotics.

Relieving Pain

Administer opioids or teach self-administration, as prescribed and as necessary, to maintain level of comfort.

Warn patient of adverse effects, such as nausea and drowsiness; watch for hypotension and decreased respirations.

Teach the use of nonpharmacologic methods, such as music, relaxation breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, distraction, and imagery to help manage pain.

Document dosage of medications and response to medication.

Make sure patient has analgesics for use postdischarge.

Patient Education and Health Maintenance

Teach care of incision.

Encourage to gradually increase activity according to guidelines given by surgeon.

Advise proper rest, nutrition, and stress avoidance while recovering from surgery.

Encourage follow-up as directed by surgeon and primary care provider to maintain immunizations.

Encourage patient to seek prompt medical attention for any infections and to contact health care provider immediately for high fever.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Respirations unlabored, breath sounds clear.

Vital signs stable, abdominal girth unchanged.

Pulses strong, extremities warm and without pallor or cyanosis.

Afebrile, no purulent drainage from incision.

Verbalizes decreased pain.

ANEMIAS

Anemia is the lack of sufficient circulating hemoglobin to deliver oxygen to tissues. Anemia has multiple causes and is commonly associated with other diseases and disorders (eg, renal disease, cancer, Crohn’s disease, alcoholism). Anemia may be caused by inadequate production of RBCs, abnormal hemolysis and sequestration of RBCs, or blood loss. Iron-deficiency anemia, pernicious anemia, folic acid.deficiency anemia, and aplastic anemia are the anemias most commonly seen in adults. Hereditary hemolytic disorders include spherocytosis, hemoglobinopathies (eg, sickle cell), and enzymatic deficiencies such as glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD). Treatments for anemia include nutritional counseling, supplements, RBC transfusions, and, for some patients, administration of exogenous erythropoietin (epoetin alfa or darbepoetin alfa), a growth factor stimulating production and maturation of erythrocytes. New erythropoiesis-stimulating agents are under development. Erythropoietin is used to stimulate RBC production in anemias associated with chronic renal failure, chemotherapy treatment, and HIV.

Iron-Deficiency Anemia (Microcytic, Hypochromic)

Iron-deficiency anemia is a condition in which the total body iron content is decreased below a normal level, affecting hemoglobin synthesis. RBCs appear pale and are small.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The most common cause is chronic blood loss (GI bleeding including occult colorectal cancers, excessive menstrual bleeding, hookworm infestation), but anemia may also be caused by insufficient intake of iron (weight loss, inadequate diet), iron malabsorption (end-stage renal disease, smallbowel disease, gastroenterostomy), or increased requirements (pregnancy, periods of rapid growth).

Decreased hemoglobin may result in insufficient oxygen delivery to body tissues.

The incidence of iron-deficiency anemia, the most common type of anemia, varies widely by age, sex, and race. In the United States, it is more than twice as common in women as compared to men, affecting 10% of non-Hispanic white women and 20% of black and Hispanic women. It is a major health problem in developing countries.

Symptoms generally develop when hemoglobin has fallen to less than 11 g/100 mL.

Clinical Manifestations

Headache, dizziness, fatigue, tinnitus.

Palpitations, dyspnea on exertion, pallor of skin and mucous membranes.

In developing world: smooth, sore tongue; cheilosis (lesions at corners of mouth), koilonychia (spoon-shaped fingernails), and pica (craving to eat unusual substances).

Diagnostic Evaluation

CBC and iron profile—decreased hemoglobin, hematocrit, serum iron, and ferritin; elevated red cell distribution width and normal or elevated total iron-binding capacity (transferrin).

Determination of source of chronic blood loss may include sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, upper and lower GI studies, stools and urine for occult blood examination.

Nursing Assessment

Obtain history of symptoms, dietary intake, past history of anemia, possible sources of blood loss.

Examine for tachycardia, pallor, dyspnea, and signs of GI or other bleeding.

Nursing Diagnoses

Imbalanced Nutrition: Less Than Body Requirements related to inadequate intake of iron.

Activity Intolerance related to decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Ineffective Tissue Perfusion related to decreased oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.

Nursing Interventions

Promoting Iron Intake

Assess diet for inclusion of foods rich in iron. Arrange nutritionist referral, as appropriate.

Administer iron replacement, as ordered. Monitor iron levels of patients on chronic therapy.

Increasing Activity Tolerance

Assess level of fatigue and normal sleep pattern; determine activities that cause fatigue.

Assist in developing a schedule of activity, rest periods, and sleep.

Encourage conditioning exercises to increase strength and endurance.

Maximizing Tissue Perfusion

Assess patient for palpitations, chest pain, dizziness, and shortness of breath; minimize activities that cause these symptoms.

Elevate head of bed and provide supplemental oxygen, as ordered.

Monitor vital signs and fluid balance.

Patient Education and Health Maintenance

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Incorporates several foods high in iron into diet; takes prescribed iron supplementation, as ordered.

Tolerates increased activity; obtains sufficient rest.

Vital signs stable without complaints of chest pain, palpitations, or shortness of breath.

Megaloblastic Anemia: Pernicious (Macrocytic, Normochromic)

A megaloblast is a large, nucleated erythrocyte with delayed and abnormal nuclear maturation. Pernicious anemia is a type of megaloblastic anemia associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Vitamin B12 is necessary for normal deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in maturing RBCs.

Pernicious anemia demonstrates familial incidence related to autoimmune gastric mucosal atrophy.

Normal gastric mucosa secretes a substance called intrinsic factor, necessary for absorption of vitamin B12 in ileum. If a defect exists in gastric mucosa, or after gastrectomy or smallbowel disease, intrinsic factor may not be secreted and orally ingested B12 may not be absorbed.

Some drugs interfere with B12 absorption, notably ascorbic acid, cholestyramine, colchicine, neomycin, cimetidine, and hormonal contraceptives.

Lower-serum vitamin B12 concentrations are associated with aging, but the evidence linking subnormal vitamin B12 to anemia in older people remains limited and inconclusive.

Clinical Manifestations

Of anemia—pallor, fatigue, dyspnea on exertion, palpitations. May be angina pectoris and heart failure in older adults or those predisposed to heart disease.

Of underlying GI dysfunction—sore mouth, glossitis, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, loss of weight, indigestion, epigastric discomfort, recurring diarrhea or constipation.

Of neuropathy (occurs in high percentage of untreated patients)—paresthesia that involves hands and feet, gait disturbance, bladder and bowel dysfunction, psychiatric symptoms caused by cerebral dysfunction.

Diagnostic Evaluation

CBC and blood smear—decreased hemoglobin and hematocrit; marked variation in size and shape of RBCs with a variable number of unusually large cells.

Folic acid (normal) and B12 levels (decreased).

Gastric analysis—volume and acidity of gastric juice diminished.

Schilling test for absorption of vitamin B12 uses small amount of radioactive B12 orally and 24-hour urine collection to measure uptake—decreased.

Management

Parenteral replacement with hydroxocobalamin or cyanocobalamin (B12) is necessary by intramuscular (I.M.) injection from health care provider, generally every month.

Nursing Assessment

Assess for pallor, tachycardia, dyspnea on exertion, exercise intolerance to determine patient’s response to anemia.

Assess for paresthesia, gait disturbances, changes in bladder or bowel function, altered thought processes indicating neurologic involvement.

Obtain history of gastric surgery or GI disease.

Nursing Interventions

Improving Thought Processes

Administer parenteral vitamin B12, as prescribed.

Provide patient with quiet, supportive environment; reorient to time, place, and person, if needed; give instructions and information in short, simple sentences and reinforce frequently.

Minimizing the Effects of Paresthesia

Assess extent and severity of paresthesia, imbalance, or other sensory alterations.

Refer patient for physical therapy and occupational therapy, as appropriate.

Provide safe, uncluttered environment; make sure personal belongings are within reach; provide assistance with activities, as needed.

Patient Education and Health Maintenance

Advise patient that monthly vitamin B12 administration should be continued for life.

Instruct patient to see health care provider approximately every 6 months for hematologic studies and GI evaluation; may develop hematologic or neurologic relapse if therapy inadequate.

Evaluation: Expected Outcomes

Oriented, cooperative, and follows instructions.

Carries out activities without injury.

Megaloblastic Anemia: Folic Acid Deficiency

Chronic megaloblastic anemia is caused by folic acid (folate) defi-ciency.

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Dietary deficiency, malnutrition, marginal diets, excessive cooking of foods; commonly associated with alcoholism.

Impaired absorption in jejunum (eg, with small-bowel disease).

Increased requirements (eg, with chronic hemolytic anemia, exfoliative dermatitis, pregnancy).

Impaired utilization from folic acid antagonists (methotrexate) and other drugs (phenytoin, broad-spectrum antibiotics, sulfamethoxazole, alcohol, hormonal contraceptives).

Clinical Manifestations

Of anemia: fatigue, weakness, pallor, dizziness, headache, tachycardia.

Of folic acid deficiency: sore tongue, cracked lips.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Vitamin B12 and folic acid level—folic acid will be decreased.

CBC will show decreased RBC, hemoglobin, and hematocrit with increased mean corpuscular volume and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration.

Management

Oral folic acid replacement on daily basis.

Nursing Assessment

Obtain nutritional history.

Monitor level of dyspnea, tachycardia, and development of chest pain or shortness of breath for worsening of condition.

Nursing Interventions

Improving Folic Acid Intake

Assess diet for inclusion of foods rich in folic acid: beef liver, peanut butter, red beans, oatmeal, broccoli, asparagus.

Arrange nutritionist referral, as appropriate.

Administer folic acid supplement.

Assist alcoholic patient to obtain counseling and additional medical care, as needed.

Community and Home Care Considerations

Encourage pregnant patient to maintain prenatal care and to take folic acid supplement.

Provide alcoholic patient with information about treatment programs and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings in the community.

NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT DRUG ALERT

DRUG ALERT RUG ALERT

RUG ALERT NURSING ALERT

NURSING ALERT

Key Decision Point

Key Decision Point