CHAPTER 4 Healthy public policy, settings and supportive environments

In Chapter 1 we outlined a continuum of health promotion approaches. At one end of that continuum is the population approach to health highlighting regulatory activities that create supportive environments for health. These activities offer scope for developing effective long-term change with wide-ranging impact on the determinants of health and illness. Regulatory activities may be developed at the international, national and local levels, or all three working in concert with one another.

WHAT IS HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY?

The regulatory activities discussed in this chapter are those activities that involve the application of legislative and financial frameworks that create opportunities for healthy living. ‘Regulatory activities include executive orders, laws, ordinances, policies, position statements, regulations and formal and informal rules’ (Schmid et al 1995 in McKenzie et al 2005: 187). These regulatory actions or healthy public policies can be for broad activities aimed at social change, change at the local/community level or change within organisations. On the continuum we outlined in Chapter 1, these activities are associated with the socio-ecological approach. In this chapter, we use the term healthy public policy, to include all of the activities defined here.

Until relatively recently health workers have been concerned primarily with health sector policy, because it was assumed that this was the major policy that impacted on health. It is now recognised that health sector policy in developed countries has a limited impact on health by comparison with the impact of social, economic and environmental policy because it focuses largely on the structure of health care delivery. Social policy, for example, deals with such issues as income distribution, housing and transport provision, while economic policy affects such things as employment rates, inflation and taxation policies. Policies that impact on the physical environment include policies on urban planning, air quality and water quality. It is clear that all of these things do a great deal to structure the environments in which people live. The notion, then, of public policies having a substantial impact on health makes good sense, and the need for economic, social and health policies to be responsive to the requirements of the community is quite apparent. Two recent results of the growing recognition of the importance of population health protection through public policy are the increasing concern for the link between health and the state of the environment, set out in Chapter 3, and concern for the impact of economic globalisation and neo-liberalism, especially in increasing inequities and impacting on the quality of life (Ife & Tesoriero 2006; Labonté & Schrecker 2006; Verrinder 2005).

Healthy public policy ‘cannot be developed in a moral vacuum’ (WHO 1998: 210). In Chapter 2 we discussed the values of equity, equality and social justice, underpinning Primary Health Care. The development of health public policy requires political will and, in particular, a commitment to equity and human rights, ensuring that all members of society receive the health benefits of social change. It is important, therefore, to understand what health policy is and how it can be influenced.

WHAT IS HEALTH POLICY?

Health policies are policies that have been considered as ‘an authoritative statement of intent adopted by governments on behalf of the public with the aim of improving the health of the population’ (Palfrey 2000: 3). There seem to be two characteristics common to all policies, whatever the context, and these are:

1. Distributive policies — the outcome of these policies are that services or benefits are provided to a particular segment of the population; for example, family allowances or baby bonuses provided by governments.

2. Regulatory policies are specific statements that have a narrow impact. They guide or control action. They usually take the form of legislation, such as the Acts concerned with food and water quality standards, and smoking.

3. Self-regulatory policies are sought by organisations or groups to maintain control of their actions. Professionals are bound by codes of practice. Contemporary relevance may be upgraded through peer review and organisations use quality assurance processes.

4. Redistributive policies are the most contested and are attempts by governments to change the distribution of income, wealth, property or rights between groups in the population. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Medicare in Australia are good examples. Both are designed to improve access to health care to the whole population. Access to services is based on need rather than the ability to pay. The form of redistributive policies is often dependent on the political philosophy of the governing authority.

THE PROCESS OF PUBLIC POLICY-MAKING

Public policy-making is a dynamic social and political process (Milio 1988: 3), but the process has also been described as ‘messy and circuitous’ (Lin, Smith & Fawkes 2007). Public policy-making is not a smooth linear progression because it must synthesise ‘power relationships, demographic trends, institutional agendas, community ideologies [and] economic resources’ (Brown 1992: 104). Evidence-based research may also inform policy development.

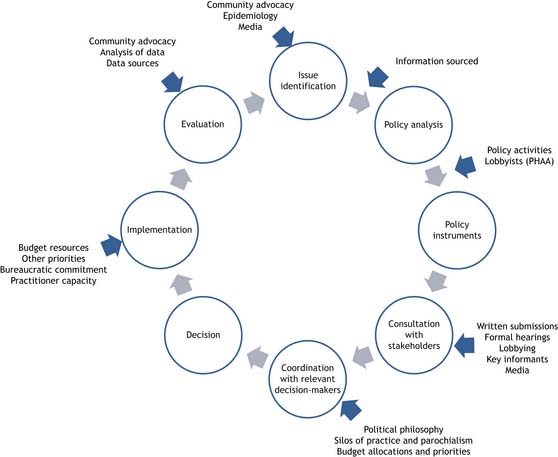

Several authors have described the public policy-making process using a variety of relatively similar models. Palmer & Short (2000) have described it as a five-stage model, and more recently Lin and colleagues (2007: 136–7) have presented the eight-stage process listed below and represented in Figure 4.1. It is important to note, however, that this model accounts only for policies that are formally developed, not those that develop incrementally and never reach the public agenda.

1. Issue identification and agenda setting — a public problem is recognised as a political issue and is placed on the political agenda. This often occurs in response to pressure from an interest group and interest from the media who both may play powerful roles in raising the public profile of an issue, defining it and portraying the perspectives around the issue and the potential impacts from the issue.

2. Policy analysis — relevant data and information is collected by those formulating the policy. Policy objectives are framed.

3. Policy instruments — options and proposals for solving key policy objectives are explored.

4. Consultation with stakeholders — key informants in industry and professions who may be affected by the policy and community organisations are canvassed for feedback on potential implications. Dugdale (2008 Ch 10) provides a very comprehensive discussion of the dilemmas for policy-makers in this process.

5. Coordination with relevant decision-makers — government departments at all levels (with the hope that new policies will dovetail with the approaches in other sectors).

6. Decision — a new policy is formally accepted, through either legal enactment in parliament or approval by the appropriate minister.

7. Implementation — the policy is translated in legislation and from there into programs and local strategies. The ‘product’ seen at this point may be quite different from what was imagined when the policy was first formulated. For example, its power may be eroded by the way in which it is implemented, or it may have unforeseen consequences when it is put into practice. The outcome of policies that are implemented with an inadequate budget may be quite different from that envisaged when they were originally formulated.

8. Evaluation — this can take various forms. Implementation processes can be monitored or assessed as to whether the policy has met the intended objectives. This may trigger re-commencement of the policy cycle.

FIGURE 4.1 The policy-making process

(Source: Adapted from Lin V, Smith J, Fawkes S 2007 Public Health Practice in Australia: the Organised Effort. Allen & Unwin, Sydney, pp 136–7)

In health promotion, regulatory activities such as international laws that address issues such as pollution of the oceans, national laws such as quarantine and local laws such as garbage disposal, are developed for the ‘common good’. These healthy public policies may be as controversial as the redistributive polices, previously described. These laws invariably infringe upon the rights of individuals. Whatever the level of policy development, the same principles apply. In health promotion, the philosophy of Primary Health Care needs to underpin the policy development process to maximise the health of the population. Ideally, the need should be identified by the community and the policy developed with community and expert knowledge combined with the experience of policy-makers. This collective wisdom will make it socially acceptable to most and scientifically sound.

HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY — FROM INTERNATIONAL TO ORGANISATIONAL: THE EXAMPLE OF TOBACCO

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

The WHO FCTC is the first legal instrument designed to reduce tobacco-related deaths and disease worldwide. The convention has provisions that set out international minimum standards on tobacco-related issues, such as tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, tax and price measures, packaging and labelling, illicit trade and protection from second-hand smoke. These provisions are designed to guide governments, which are free to legislate at higher thresholds if desired (WHO 2005). Australia was actively involved in the development of the WHO FCTC and ratified it on 27 October 2004.

Australia’s tobacco strategy

Further use regulation to reduce the use of, exposure to, and harm associated with tobacco

Further use regulation to reduce the use of, exposure to, and harm associated with tobacco

Increase promotion of Quit and Smokefree messages

Increase promotion of Quit and Smokefree messages

Improve the quality of, and access to, services and treatments for smokers

Improve the quality of, and access to, services and treatments for smokers

Provide more useful support to parents, carers and educators helping children to develop a healthy lifestyle

Provide more useful support to parents, carers and educators helping children to develop a healthy lifestyle

Endorse policies that prevent social alienation associated with the uptake of high risk behaviours such as smoking, and advocate for policies that reduce smoking, as a means of addressing disadvantage

Endorse policies that prevent social alienation associated with the uptake of high risk behaviours such as smoking, and advocate for policies that reduce smoking, as a means of addressing disadvantage

Tailor messages and services to ensure access by disadvantaged groups

Tailor messages and services to ensure access by disadvantaged groups

Obtain the information needed to fine-tune our policies and programs.

Obtain the information needed to fine-tune our policies and programs.

Victoria’s Tobacco Action Plan

The Victorian Tobacco Control Strategy 2008–2013 is in the developmental stage. However, regulatory activities to create supportive environments for health have been part of the State of Victoria’s landscape for some time. The purpose of the Tobacco Act 1987, for example, was to prohibit certain sales or promotion of tobacco products and to establish the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth). Since then many statutory regulations have emerged to regulate sales, advertising, labelling and pricing of tobacco in Victoria. Recent developments in tobacco control in Victoria include smoke-free dining, point-of-sale tobacco advertising and display restrictions, and smoking restrictions in bars, clubs and gaming venues. Future statutory restrictions on smoking in private cars when children are present are currently planned. The Victorian State Government provides information and support to local governments as well. This service is designed to assist local governments in conducting their education and enforcement responsibilities under the Tobacco Act 1987. It provides local councils with information, resources and training for Environmental Health Practitioners who are responsible for enforcing the Act.

From policies to strategies

The development of healthy public policy for any issue at a broad social level, at local/community level, and within organisations will create a supportive environment for health. The development of the policy may be ‘bottom-up’ or ‘top-down’ depending on the level and processes of development. Influencing the policy may be done at any stage in its development (as set out in Figure 4.1).

HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY; SETTINGS AND SUPPORTIVE ENVIRONMENTS

Policy development at the local level lends itself to the settings approach to health promotion.

Healthy Cities project

a model that can adapt to local conditions

a model that can adapt to local conditions

ability to juggle competing demands

ability to juggle competing demands

strongly supported community engagement that represents genuine partnerships

strongly supported community engagement that represents genuine partnerships

recognition by a broad range of players that healthy cities is a relatively neutral space in which to achieve goals

recognition by a broad range of players that healthy cities is a relatively neutral space in which to achieve goals

effective and sustainable links with a local university

effective and sustainable links with a local university

an outward focus open to international links and outside perspectives

an outward focus open to international links and outside perspectives

the initiative makes the transition from a project to an approach and way of working.

the initiative makes the transition from a project to an approach and way of working.

INSIGHT 4.1 Walk Bendigo — a pedestrian-focused city centre

Streets that provide a high quality pedestrian environment have been demonstrated to be associated with many positive health and community outcomes. In high quality pedestrian environments, more people walk,2 rents and land prices are higher3 and with more pedestrians retailers can capture additional trade. With more people walking, the negative health effects associated with a sedentary lifestyle are minimised4 and there are greater opportunities for social interaction and community connectedness. ‘Walking is a special mode of transport; it not only gets you from A to B, but it also helps cut crime, build a strong community and keep you fit.’5

Walk Bendigo aims to create a continuous pedestrian network14 through the City rather than a vehicular network. A new form of intersection will have pedestrians and vehicles together on ‘raised table’ shared surfaces. Instead of pedestrians crossing the road surface, vehicle drivers will cross an extended footpath. The intersections will be treated as a quality pedestrian space with surfacing and fittings designed to match the existing palette of the City’s urban materials. The design of intersections and streets and the design of footpaths become integrated so as to maintain a consistent horizontal and vertical alignments for the pedestrian while the vehicles rise up to footpath level in order to cross the now pedestrian dominated space. The higher urban amenity and reduced speeds will create safer pedestrian spaces and encourage more pedestrian activity.

Tim Buykx (Coordinator, Landscape and Open Space Planning, City of Greater Bendigo)Note: References for the article in Insight 4.1 are available on the Elsevier EVOLVE website.

Municipal Public Health Planning

The Municipal Public Health Planning Framework in Victoria, Australia, is an excellent example of healthy public policy development. Environments for Health: Promoting Health and Wellbeing Through Built, Social, Economic and Natural Environments (State Government of Victoria 2001a) is an initiative of the State Government of Victoria that is consistent with the legislative planning requirement of the Victorian Health Act (1958) and the Local Government Act 1989 in that state. The framework was developed in partnership with the Public Health Division of the Department of Human Services, the Municipal Association of Victoria, Victorian Local Governance Association, local governments and community groups. It is a strategy for public health planning that aims to systematically address ‘individual, organisational, community, social, political, economic and other environmental factors affecting health and wellbeing’ (State Government of Victoria 2001b). The legislation that underpins this strategy ensures that Municipal Public Health Plans (MPHP) are reviewed annually and prepared every three years. Most local governments are using the Environments for Health framework to develop their plans (see Box 4.1). Application of the framework to local issues and actions means that MPHPs are very diverse across the state.

BOX 4.1 Environments for health: promoting health and wellbeing through health planning concepts

The MPHP framework uses the strengths of a number of approaches to public health planning including:

• Strategic local area planning A strategic and integrated approach to municipal public health planning promotes a model for integrating physical, social and economic planning, with community participation.

• Social model of health Participation, sense of community and empowerment are interdependent social factors contributing to individual and community wellbeing.

• Health-promoting systems A strong relationship exists between people and place: people’s health and wellbeing reflects their socioeconomic status, and accordingly, where they live. Different locations afford varying degrees of access to healthy environments, food, services, amenities, health information, education, employment, housing and opportunities to experience a sense of community and sense of place. A holistic approach ensures that the interrelationships between all major issues impacting on individuals and families within the context of their local communities are taken into account (see Appendix 2).

• Focusing on health outcomes Utilising information from the Victorian Burden of Disease Study (Victorian Health Information Surveillance System [VHISS] 2001) and other sources can identify issues and areas for consideration when planning health priorities.

• Participation and partnership approaches People increasingly share in planning and decision-making and are empowered to affect the outcome of the process. Clients, community groups, government departments and other agencies need to participate in health planning, not only to ensure a match between local needs and priorities, but because participation itself promotes health. Clients/consumers and the wider community need to participate meaningfully to ensure appropriateness, community ownership of processes, programs and outcomes, and the promotion of accountability to the community for decisions on priorities and resource allocation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree