Chapter 6. Healthy children

Introduction

The governments of most Western nations have declared their commitment to the health and wellbeing of their communities by promoting and supporting child health initiatives. Australia and New Zealand share this commitment. Compared with children in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, children in this part of the world are doing relatively well, but there are still areas for improvement. The past several years have seen declining rates of mortality related to injuries, and declining hospitalisations for asthma. There have been improved survival rates for children with leukaemia, greater immunisation coverage, and increases in the number of children meeting national physical activity guidelines and reading and numeracy standards (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2009a).

One of the greatest indicators of health and wellness in a community is the extent to which it invests in and nurtures its children.

However, other benchmarks require attention, including rising rates of severe disability, diabetes and tooth decay. This indicates a need to keep up the momentum towards better health for children, promoting safety and oral health. Another challenge lies in trying to reduce the time children spend in front of a television or computer screen, and increasing their physical activity. In addition, there is a need to support parents in promoting healthy lifestyles, harmony in the home, and sustaining sufficient resources to circumvent risks to family life. As nurses and midwives, we must also remain vigilant to ensure that families at risk of injury, low socio-economic status (SES), a lack of access to services or with relationship difficulties are brought to the attention of those agencies that can help them. This also includes drawing attention to the education system and those who allocate resources to promote equity of access for rural, remote and Indigenous children.

Disadvantage among Indigenous children and their families is by far the most urgent issue for all health professionals. We have a major role to play in helping communities achieve equitable health outcomes by drawing attention to the disparities, and framing solutions in terms of primary health care (PHC). This is a major priority of government health strategies in both Australia and New Zealand (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2009a, Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2001 and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2002a). It will be important for current and future generations of Indigenous children to work towards an evidence base for health policy and planning. Nursing and midwifery research can add value to this by gathering important data from our communities, showing not only the importance of an early, healthy start to life, but the local contextual strengths and constraints that impact on healthy childhoods.

One of the most pressing issues in both Australia and New Zealand is the inequitable disadvantage experienced by Indigenous children in both countries.

The healthy child

Healthy children can be defined on the basis of a wide variety of indicators. Being born healthy gives a child a head start, whereas coming into the world with a disability or some form of abnormality compromises a child’s chance of good health. After birth, health also depends on the family, and having opportunities to lead a healthy, nurtured and well-nourished lifestyle with a minimum of stress. Children’s health is a product of receiving warm and consistent parenting, a good educationand health services when these are required; and having more protective factors in their environment than risk factors. These determinants of healthy childhood are underpinned by several theories of child health and development.

A healthy child is one that experiences warm and consistent parenting, a good education, receives health services when needed, and has access to more protective and fewer risk factors in their environment.

For example, Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) theory of social ecology or ‘bioecology’ focuses on interactions between the child, parental care and features of the family’s environment. The resources a family brings to these interactions include income, time, and human, psychological and social capital (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1995 and Zubrick et al., 2000). In combination, these resources help parents build the capacity to support child health and development in the context of their community and society (Li et al 2008).

Another theory, self-efficacy theory, explains how parents make decisions about their behaviour (Bandura 1977). This perspective argues that individuals choose behaviours they believe will lead to certain outcomes, which they usually believe

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 identify the most important influences on child health in contemporary society

2 describe the major risk and protective factors that influence child health

3 develop a set of community level strategies for promoting good parenting

4 explain how you would assess the resource base in any given community for supporting child health

5 describe how you would use the principles of primary health care to create a model for child health promotion in the community

6 identify the nursing roles that provide a common base of expertise for child health and parenting across a range of settings (school, clinic, home visiting, play groups).

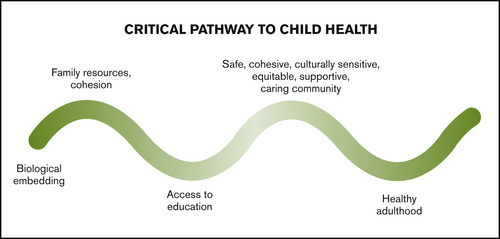

Biological embedding and childhood stress

Children begin life with a set of predispositions, biologically embedded to respond to what lies within the sphere of their life. This ‘biological embeddedness’ provides a template for interactions between children and the array of social and environmental circumstances of their lives, as they develop. Children’s interactions with the world around them at ‘critical moments’ (times of heightened sensitivity) along their developmental pathway determine their endocrine, neurological, cardiovascular and immunological development, and how they learn to modify incoming stressors (Hertzman, 2001a, Hertzman, 2001b, Mustard, 1996 and Mustard, 1999). Critical pathway interactions are therefore instrumental to children’s development. They provide opportunities for children to embed health enhancing behaviours in the early stages of their lives, which literally helps ‘sculpt’ their developing brains to build their coping capacity for later life (Mustard 2007).

Children’s interactions with the world around them at ‘critical moments’ in their development help them embed healthy behaviours in the early stages of their lives.

In some cases, children’s cultural, spiritual and physical environments allow them to use their biological strengths to greater advantage. In other cases, children fail to reach their potential because of socio-cultural determinants. These can include cycles of intractable poverty, or a lack of healthy policies for child support, or a lack of high-quality day care, adequate parental support or environmental protection. Instead of enhancing their coping capacity, certain combinations of these social factors may conspire to stifle a child’s ability to be nurtured in the community (Shonkoff et al 2009). This can create inequalities for children that persist into adult life in two ways. The first is by accumulating damaging adversities during sensitive developmental periods. So, for example, traumatic exposure to psychologically and physically stressful experiences during a very early sensitive period of life could establish effects that become permanently incorporated into the child’s regulatory physiological processes.

Current research has found that these physiological mechanisms can lead to coronary artery disease, cancers, alcoholism, depression and substance abuse, as well as being linked to obesity, physical inactivity and smoking (Shonkoff et al 2009). For this reason, interventions to deal with these diseases in adulthood are nowhere near as effective as ensuring a healthy childhood relatively free from stress. An alternative explanation to why childhood stress leads to adult diseases is called ‘weathering’ of the body, which occurs under persistent adversity (Shonkoff et al 2009). In this situation, the increased wear and tear induced by too many stressful experiences deregulate and overuse the pathways that were originally designed for an individual’s adaptation to stress. This accelerates the ageing processes. Cumulative exposure to stress creates an ‘allostatic load’ which activates stress management systems in the brain to the extent that they become pathogenic instead of adaptive (Shonkoff et al 2009).

Exposure to psychologically and physically stressful experiences in childhood can impact on health as an adult.

Socio-economic factors and childhood stress

Pathogenic effects can be created when children live in impoverished families, where they can be exposed to numerous stressors. These stressors include such things as maltreatment, traumatic fear, family conflict and/or chaos, inadequate nutrition, recurrent infections, having mentally unstable or absent parents, punitive parental behaviour, neighbourhood violence and dysfunctional schools (Shonkoff et al., 2009 and Waldegrave and Waldegrave, 2009). Research shows that these social stressors affect many children from lower SES backgrounds through heightened activation of their stress-responsive systems (Shonkoff et al., 2009 and Waldegrave and Waldegrave, 2009). Because of this burden of stress it may be impossible to completely reverse the neurobiological and health consequences of growing up poor. On the other hand, an emerging body of research is showing that positive parent–child interactions, exposure to a new vocabulary and stability of parental responsiveness can actually alter a child’s physiological responses (Hackman & Farah 2009). Parental social support, especially from family members, and having the support of services and schools can help moderate the impact of adverse circumstances for children (Zubrick et al 2008). Stress in children can therefore be buffered by stable and supportive relationships at the family, community and societal levels (Shonkoff et al., 2009 and Zubrick et al., 2008). This is cause for optimism in promoting child and family health.

As mentioned in the previous chapter, the quality of the parental relationship is a significant influence that can lead to either sensitive parenting or disruptive relationships between parents and their children (Finger et al 2009). This reflects the importance of focusing on intergenerational health. Where the community and society provide supportive environments for families, there is a greater likelihood that parents will make healthy choices for parenting practices, and personally, modify any risky behaviours that leave them vulnerable to ill health. This, in turn, affects the likelihood of their children leading healthy lifestyles.

The quality of the parental relationship has a significant influence on the relationship between parents and their children.

Clearly, investing in children and their parents should be the major priority for ensuring good health across the life course and across the population (Shonkoff et al 2009). This is illustrated in Figure 6.1.

Global child health, disadvantage and poverty

The health of the world’s children is of concern to everyone who claims global citizenship. Most children in the world are cared for and loved, but other children suffer from violence, exploitation and abuse. Approximately 200 million children globally are not achieving their full development potential (Commission on the Social Determinants of Health [CSDH] 2008). Every day, more than 2000 die from an injury (World Health Organization [WHO] 2008b). In some regions, children are sexually abused or forced into child marriages, while others may be trafficked into exploitative conditions of work. Just over one billion children under the age of 5 live in the midst of armed conflict (United Nations Childrens Fund [UNICEF] 2009). Infant mortality is improving in some countries, but in the African countries, rates have either stagnated or lost ground, primarily due to poor access to health care (WHO 2008a). Although there have been some improvements in countries where there has been greater access to water, sanitation, drugs and antenatal care, globally, there are still nearly 10 million child deaths per year (WHO 2008a).

While most children in the world are cared for and loved, more than 2000 children a day die in the world as the result of an injury, and over 1 billion children under the age of 5 live in the midst of armed conflict.

In addition to these poor morbidity and mortality rates, global and national inequities are not being resolved, especially in developing nations. Approximately 51 million children are not registered at birth, leaving them without the protection they should have from social institutions (UNICEF 2009). In 33 countries, less than half of all births are attended by health professionals (WHO 2008a). More than one-third of young women in developing countries were married as children (UNICEF 2009). More than 70 million girls have undergone female genital mutilation, and 150 million children aged 5–14 are engaged in child labour. Others are trafficked into prostitution or other forms of exploitation (UNICEF 2009). Child poverty is also persistent. Despite worldwide attention to child poverty throughout the past 100 years, about 600 million children continue to live in absolute poverty, trying to survive on less than $US1 per day (UNICEF 2007). The main problem in many of these countries is an actual expansion of disparities between the wealthy and the poor, which leaves many poor children with little hope for the future (WHO 2008a).

In the countries of the West, relative child poverty continues to be a major problem. Relative poverty refers to those children living in homes receiving less than 50% of the median national income, and this affects approximately 15% of children in Australia and New Zealand (Emerson 2009). The effects of living in relative poverty have been demonstrated in a wide-ranging body of research (Emerson 2009), summarised in Box 6.1.

BOX 6.1

High infant mortality

High unintentional injury rates

Low birth weight

Poor overall child wellbeing

Low immunisation rates

Juvenile homicide

Low educational attainment

Non-participation in higher education

Dropping out of school

Aspiring to low-skilled work

Poor peer relations

Bullying at school

Teenage pregnancy

Physical inactivity and childhood obesity

Not having breakfast

Mental health problems, including loneliness

(Emerson 2009)

An interesting analysis of young people’s perspectives on poverty was conducted in the United kingdom (UK) to see how the children themselves experienced disadvantage (Redmond 2008). A review of nine studies where children’s views were sought found that children living in relative poverty were not as concerned about the lack of resources as they were about family relationships and being excluded from activities that their peers can access (Redmond 2008). Social exclusion therefore had the most profound impact on their lives as a result of relative poverty. This was experienced in not being able to access the tools of virtual communication (phones, computers) to connect with their peers. The children coped with this type of social exclusion by relying heavily on family life to help them cope. For children who live in rural and remote areas, these effects are even more intense. Some children adapt to these difficulties with resourcefulness and optimism, while others experience anxiety, pessimism and reduced aspirations for the future (Redmond 2008).

Children and homelessness

At the extreme end of poverty, a growing number of children are rendered homeless, even in the wealthiest countries. Homelessness is a source of grave concern in the United States, where in a CNN poll found that 1 in 50 American children faced homelessness in 2005–06 (Online. Available: www.cnn.com/2009/US/03/10/homeless.children [accessed 14 October 2009]). In Australia during the financial crisis of 2008–09, homeless families with children accounted for one-quarter of the homeless population of nearly 79000 (AIHW 2009b). In New Zealand, homelessness is a largely invisible problem, with some imprecision in the number of homeless. Although Statistics New Zealand released a formal definition of homelessness in 2009 (Statistics New Zealand 2009), there are also cases of ‘concealed homelessness’, a situation where people have no other option but to share someone else’s accommodation. This is a growing concern.

While few children in Australia and New Zealand live in absolute poverty, relative poverty is a significant issue for children in both countries.

In addition to having a lack of housing, there has been a growing trend towards women and children using women’s refuge services as temporary safe housing (National Collective of Women’s Refuges 2007). The negative health and social impact of this situation is an immediate problem, as these children are prone to injury, violence and behavioural problems. It is a social tragedy in wealthy countries. Although some cases of homelessness are a result of families becoming victims of changing socio-economic circumstances, other cases of child homelessness reflect parental neglect or abuse. Children who have been neglected or abused have the same types of negative developmental outcomes as mentioned opposite in Box 6.1, particularly lower social competence, poor school performance and impaired language ability (AIHW 2009a; Waldegrave & Waldegrave 2009). In addition, child victims of maltreatment or abuse do not acquire the skills to be self-regulating, which interferes with their ability to control emotions and behaviour. This impedes the development of independence and self-sufficiency later in life (Schatz et al 2008). A longitudinal study of New Zealand children found that children with severely disturbed childhood behaviours have a number of risks in later life, including the risk of committing violent offences, attempting suicide and becoming teenage parents (Fergusson et al, in WHO 2009a). As others have found, the residual effects of child abuse often last throughout the child’s life, especially among those who have been sexually abused, and those who do not disclose the abuse (Ming Foynes et al 2009; Pereda et al 2009). As we mentioned in Chapter 5, some victims of abuse grow up to become perpetrators of abuse themselves (AIHW 2008).

Indicators of child health in Australia and New Zealand

A comprehensive report on child health in Australia in 2009, indicates where progress has been made in reducing risk and increasing protective factors, and identifies health issues that continue to be problematic (AIHW 2009a). No similar barometer of child health has been reported for New Zealand children, although a monitoring framework provides the basis for key indicators of child health (Craig et al 2007). What we do know from recent comparative data is that New Zealand lags behind Australia in a number of international child health indicators, including infant mortality rates, immunisation, deaths from accidents and injury, relative income poverty of children and material wellbeing of children (UNICEF 2007).

New Zealand lags behind Australia in a number of key child health indicators, including infant mortality, immunisation and relative income poverty of children.

The main health issues for children in Australia are mental disorders, chronic respiratory conditions such as asthma, and neonatal conditions. As in other Western nations, injuries are the leading cause of death in children aged 1–14, with 10–14-year-old boys having 2.5 times the rate of injuries for girls in this age group. For all Australian children the leading causes of injuries are falls, land transport accidents, accidental poisoning, burns, scalds and assault. The other most prevalent conditions causing childhood deaths are cancers and diseases of the nervous system (AIHW 2009a). Injury deaths have been reduced over the past decade because of fewer land transport accidents, accidental drowning and submersions. Infants have the highest rates of injury death of all children’s age groups, although infant mortality can be due to factors related to pregnancy. The mortality rate among infants and young children have steadily declined as a result of adequate neonatal intensive care units, increased community awareness of risk factors for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and the rate of childhood immunisation, which covers 93% of Australian 2-year-olds. The rate of Australian infant mortality and childhood deaths compares favourably with other OECD countries in ranking, just above the median level, but only for non-Indigenous children.

New Zealand children are most likely to be acutely hospitalised for injuries/poisoning, gastro-enteritis and asthma. Arranged admissions to hospital are most often for cancer/chemotherapy and dental conditions, with the most common reason for children’s hospital admissions in 2004 being insertion of grommets (Craig et al 2007). In the same year, SIDS (now often referred to in New Zealand as sudden unexpected death in infancy or SUDI), was the most common cause of mortality for children aged under 1 year, with injuries the most common cause for children over the age of one. As is the case for Australian children, the leading causes of injury among children were motor vehicle accidents and falls. Drowning also figured highly among causes of death among New Zealand children (Craig et al 2007).

Health indicators for Indigenous children

Although infant mortality has halved in the years 1986–1998 in Australia, since 2006 it has been comparatively stable in Indigenous children (AIHW 2009a). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) children experience a significantly higher rate of under 5 mortality than non-Indigenous children, including three times higher infant mortality, and three times as many childhood injuries. Half of all Indigenous infant deaths are due to perinatal problems; low birth weight and complications of pregnancy, with congenital conditions and diseases like SIDS being responsible for the remainder. Indigenous children are nearly five times more likely to die of SIDS. They are also eight times more likely than non-Indigenous children to be the subject of child protection orders for child abuse, neglect and maltreatment. Injury deaths are also more than four times greater in remote areas, where many Indigenous children live.

Indigenous children in Australia and New Zealand are at greater risk of poor health outcomes than non-Indigenous children in both countries.

New Zealand’s Indigenous children are also at greater risk of poor health outcomes than non-Indigenous children. When Maori children in New Zealand are born, they are more likely than European children to have a low birth weight, die in infancy, enter primary school with poorer hearing, have oral health problems, have experienced respiratory issues, and be at greater risk of unintentional injuries (Dyall 2007). Maori children are also more likely to be exposed to domestic, sexual and criminal violence in the home (Dyall 2007).

Chronic illnesses in childhood

The chronic conditions of asthma, diabetes and cancer are increasing in Australian children, with 40% experiencing at least one condition of 6 months or more duration, and boys suffering disproportionately (55%). Indigenous children have a greater prevalence of chronic conditions and hospitalisation rates than non-Indigenous children as well as a 30% greater prevalence of disabilities (AIHW 2009a). Among all Australian children, there has been a significant increase in type 2 diabetes over the past decade, more so for girls. The incidence of cancers among children has remained relatively stable over this time, with improved survival because of advanced treatments, and a decline in mortality. Cancer prevalence is greater in boys than girls (55%). The proportion of Australian children having allergies and asthma is equal highest (with Costa Rica) among OECD countries, whereas the prevalence of other chronic conditions is relatively similar to the other countries.

Children in New Zealand experience similar chronic conditions to Australian children. New Zealand has one of the highest reported occurrences of asthma in the world, with 25% of children reporting asthma symptoms (Howden-Chapman et al 2008). Although overall hospital admissions for asthma have declined over the past decade, ethnic disparities persist with higher rates for Maori and Pacific children than for European children (Craig et al 2007). While it is acknowledged that childhood obesity and associated type 2 diabetes are increasing in prevalence among New Zealand children, figures are not readily available. However, it is known that, like other conditions, Maori and Pacific children are over-represented in obesity and diabetes statistics (Kedgley 2007).

The chronic conditions of asthma, diabetes and cancer are increasing among Australian and New Zealand children.

Cancer is relatively rare among New Zealand children, with leukaemia accounting for approximately one-third of all cases (Craig et al 2007). Cancer prevalence is, however, increasing across all types, but with a corresponding decrease in mortality, which is expected to continue into the foreseeable future (Craig et al 2007).

Approximately 8% of Australian children and 11% of New Zealand children have disabilities that interrupt their interactions and effective participation in society, with physical disabilities more common in girls, and intellectual disabilities more common in boys. Disabling conditions among children range from moderate impairments for home and school life to those that severely limit core activities of development and require lifelong support (AIHW 2009a; Craig et al 2007).

Approximately 8% of Australian children and 11% of New Zealand children experience some type of disability that interrupts their ability to participate in society.

Other indicators of child health and wellbeing include having good dental health, physical activity and nutrition, and being breastfed from birth (AIHW 2009a). Internationally, dental health is improving due to better public health programs, water fluoridation, and improved oral hygiene and disease management (AIHW 2009a). Figures on the oral health of Australian children are not current, but it appears that they are above the OECD standard on the number of tooth decays. In New Zealand, however, the figures are concerning, with no improvement in the rate of dental caries since the early 1990s. Only 50.7% of 5-year-olds in New Zealand live in communities with fluoridated water supplies (Craig et al 2007).

Nutrition, physical activity and the social determinants of child health

In terms of nutrition and physical activity, most Australian and New Zealand children meet the national guidelines of 60 minutes of activity every day, but very few meet the nutrition standard for fruit and vegetable consumption (AIHW 2009a; Craig et al 2007). In addition, only one-third report that they conform to the ‘screen guidelines’, which recommend no more than 2 hours of non-educational screen time (computers, video, TV) per day. These guidelines are based on the fact that children who engage in more than 2 hours of screen time per day are more likely to be overweight; be less physically active; drink more sugary drinks; snack on foods high in sugar, salt and fat; and have fewer social interactions (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation [CSIRO] 2009).

Although most Australian and New Zealand children are within a normal weight range, approximately one-fifth of Australian children and one-tenth of New Zealand children are overweight or obese (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2009a and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2008a). Those who are disadvantaged socially, economically and geographically are at increased risk of becoming overweight due to a lack of available, accessible and affordable fresh fruit and vegetables and opportunities for exercise. Pacific children in New Zealand are 2.5 times, and Maori children are 1.5 times more likely to be obese than other children (MOHNZ 2008a). The majority of children are also active, meeting the standard of 60 minutes a day of some kind of physical activity, but nearly one-quarter do not meet this benchmark (AIHW 2009a). Children’s nutrition and physical activity patterns have attracted worldwide attention because of the ‘obesity epidemic’ in many nations. The obesity epidemic has attracted widespread attention because it is commonly understood that the most prevalent cause of morbidity and mortality in adults in the 21st century are non-communicable cardiovascular and metabolic diseases (WHO 2008a). The most useful way to analyse these disease patterns and their causes in the population should begin with an examination of children’s health, and the critical events that occur along the pathway to adulthood that instigate and perpetuate these diseases in epidemic proportion. A significant element of this type of analysis lies in analysing the social determinants of poor eating behaviours and inactivity patterns and the way these may be contributing to the obesity epidemic.

Most Australian and New Zealand children meet recommendations for daily exercise, but few meet the standards for fruit and vegetable consumption.

Many researchers into obesity have focused on genetics, physiology, race/ethnicity, personal responsibility and freedom of choice, effectively creating the impression that inappropriate diets are either destiny or unwise choices (Drewnowski 2009). However, increased attention has been drawn to obesogenic food environments and the importance of economic factors as social determinants of poor eating habits (Drewnowski 2009). For example, low-income neighbourhoods tend to have many fast-food outlets and convenience stores, which encourages consumption of inexpensive foods with refined grains and high sugar and fat content. On the other hand, people living in affluent neighbourhoods have the wealth and access to healthy, low-fat foods. This difference in access illustrates the role of social inequality in dietary behaviour (Drewnowski 2009). Other studies take a more socio-cultural approach, arguing that poor dietary habits are environmental and intergenerational, the result of how the family environment socialises and controls a child’s eating habits (Kime 2008). This perspective contends that the lack of structure in contemporary family life creates a more haphazard and less ordered way of eating that is sometimes chaotic, and can lead to less nutritious patterns of food consumption (Kime 2008). The other critical issue relevant to good nutrition is breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding

The research evidence supporting the health benefits of breastfeeding is unequivocal (AIHW 2009a). Compelling evidence suggests that breastfeeding protects infants against infectious diseases, including gastrointestinal illness, respiratory tract infections and middle ear infections (WHO 2005). Other possible benefits include a reduced risk of SIDS, type 1 diabetes and some childhood cancers, although the link between breastfeeding, asthma and childhood allergies is less certain (AIHW 2009a; Bryanton et al., 2009 and Kramer et al., 2007). Having been breastfed may also reduce the incidence of high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity and diabetes later in life, and improve cognitive development (Horta et al 2007). More exclusive and longer periods of breastfeeding show the strongest associations between breastfeeding, lower rates of infant illnesses and better cognitive development (AIHW 2009a).

The benefits of breastfeeding for both infant and mother are extensive. Nurses and midwives have an important role in supporting breastfeeding mothers and normalising the breastfeeding process.

Benefits of breastfeeding also extend to the mother, improving recovery after childbirth, reducing the risk of ovarian cancer and possible reduced risk of breast cancer, post-menopausal hip fractures, osteoporosis and maternal depression (Ip et al., 2007 and Productivity Commission, 2009). Breastfeeding is also thought to improve mother–infant bonding and secure attachment (Allen and Hector, 2005 and Bryanton et al., 2009). For these reasons, the WHO (2009b) guidelines recommend exclusive breastfeeding to 6 months of age.

No national studies on breastfeeding among Australian mothers have been conducted to date, so figures vary according to the state of residence. However, data collected for the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) on 5000 families show that 91% were breastfed at birth, and 46% continued to 4 months, with 14% continuing to the 6-month period as recommended by the WHO (2009b). New Zealand figures indicate that 70% of infants are exclusively breastfed at 6 weeks of age, at 3 months just over 50% of infants are exclusively breastfed, and by 6 months this has dropped to approximately 7.5% (MOHNZ 2008a). Of the latter, most were women who did not have to return to the workplace during that period of time (Zubrick et al 2008). The link between breastfeeding and work schedules confirms the complexity of breastfeeding behaviour in relation to the combination of individual and environmental factors (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). As revealed in the Australian National Review of Maternity Services, these include the health and risk status of mothers and infants, their SES, education, knowledge and skills, and support in the hospital, workplace, community, and policy environments (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). The review also cites a study in New South Wales, which found that mothers who returned to work fewer than 10 hours per week or who were self-employed had the highest rates of breastfeeding (Hector et al 2005).

The UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative has been a significant factor in increasing breastfeeding rates globally.

A Queensland study of the influence of psychological factors on breastfeeding duration also identified factors that predict breastfeeding (O’Brien et al 2008). These include the mother’s anxiety level, whether or not she had an optimistic disposition towards breastfeeding, self-efficacy, faith in breast milk for her baby, expectations and planned duration of breastfeeding prior to the birth, and the timing of making the decision to breastfeed (O’Brien et al 2008).

This body of research contributes important insights into the issues that may help encourage mothers to breastfeed. At the global level, the most significant factor in encouraging higher rates of breastfeeding in recent years has been the UNICEF Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative, which began in 1992 (Online. Available: http://unicef.org.au/GetInvolved-Subs.asp?GetInvolvedID=99 [accessed 23 October 2009]). This is a structured method of encouraging breastfeeding, which has been adopted by a number of hospitals throughout the world as a consistent method of encouraging breastfeeding. However, women’s busy lives outside the home and an early return to work after childbirth can run counter to successful breastfeeding, especially where workplace practices constrain a woman’s ability to breastfeed her child. Clearly, family-friendly workplace strategies could go a long way to extending the rates of breastfeeding to meet the WHO guidelines. Community and peer support have also been identified as important to persevering with breastfeeding, and these will be incorporated into a future National Breastfeeding Strategy for Australian mothers to be developed in 2010 (Australian Health Ministers 2009). The development of a breastfeeding helpline (1800 MUM 2 MUM) is also expected to demonstrate a favourable impact on breastfeeding rates once national data are collected from users of this service (Commonwealth of Australia 2009).

Healthy pregnancy

The fruits of a healthy pregnancy are celebrated daily, throughout the world. For some mothers, though, a healthy pregnancy is a conquest of the human spirit over dire social circumstances, made worse by a lack of care and support. In developing countries, the rate of accessing antenatal care steadily increased throughout the 1990s, notably in countries like Indonesia and other parts of South-East Asia. However, in some areas, lack of access to care can place both mother and child in a perilous situation, especially if there are other co-morbid conditions, such as malaria or HIV/AIDS (WHO 2005). In response to this situation, the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) recommends a global comprehensive strategy to provide mothers and children with a continuum of care from pre-pregnancy through pregnancy and childbirth to the early years of a child’s life (CSDH 2008). Their recommendations also include support for exclusive breastfeeding initiation within the first hour of life and for the first 6 months, skin to skin contact immediately after birth, extended breastfeeding to age 2, and educational support for children and their mothers. If these recommendations were adopted worldwide, it would have an intergenerational effect, shaping lifelong trajectories and opportunities for health as well as promoting mothers’ educational attainment as a way of countering gender and other inequities (CSDH 2008).

A healthy pregnancy is one of the key determinants for achieving a healthy childhood.

Other risks to healthy pregnancy lie in the workplace. Many pregnant women maintain full-or part-time employment, exposing them to workplace hazards. Others may be exposed to dangerous conditions in their home, neighbourhood or community. In any of these settings, the availability of sufficient nutritious food is an important influence on healthy pregnancy. A nutritional diet in pregnancy should have a high intake of fruits, plant foods and calcium and low intake of fat, salt, sugar and alcohol. Research also indicates that folic acid, one of the B vitamins, should be taken by pregnant women to help prevent spina bifida and other neural tube defects (AIHW 2008). Another important goal of pregnancy is to ensure that both parents are in good health and free from infections, harmful drugs or other substances that can interfere with the construction of a healthy child. It is important for expectant parents to understand the multiplier effects of all factors, to gain a clear understanding of how lifestyle factors can interact with biological or genetic factors and environmental circumstances to either enhance or override a child’s healthy development.

Antenatal care

Antenatal care by a health professional from the earliest stages of pregnancy can help pregnant women and their partners identify the need for any dietary or lifestyle changes and ways of sustaining those changes throughout the pregnancy and beyond the birth of the child. It also provides an opportunity to help parents create the emotional foundations for the child’s life; one of the most important elements of early parenting.

Effective antenatal care provides an opportunity for parents to create the emotional foundations for a child’s life.

Ultrasound examinations and population studies show that from about 10 weeks, an infant moves spontaneously, and by 15 weeks, movements may be felt as a reaction to the mother’s laugh or cough, suggesting a response of self-protection or self-assertion (Shonkoff & Phillips 2000). During this stage, a high level of stress in the mother can affect the function of the fetal–placental unit, compromising fetal growth and causing a risk of preterm birth or low birth weight (Hobel et al 2008). Knowledge of this early neurological development of the fetus, along with our understanding of the effects of stress on neural development during the critical periods, underlines the importance of early and ongoing antenatal care (Hobel et al 2008; Shonkoff et al 2009).

An additional goal of antenatal preparation is to establish a birth plan, one that empowers parents to make decisions on the place of birth, and the choice of birth attendant or birth companion. Yet another important opportunity afforded by antenatal visits is the chance to discuss the diagnostic approach to the pregnancy, including the choice of vaginal or caesarean birth and whether or not an induction will be indicated. Antenatal preparation also provides an opportunity for parents to talk through their emotional needs in relation to parenting, which is especially important for pregnant adolescents and first time parents. The antenatal visits can therefore act as a platform for planning and empowerment as a parent. They provide an opportunity to establish a trusting relationship with a health professional and open up channels of communication that will help women develop the skills for lifelong decision-making (WHO 2005). Birth preparation includes gathering information about breastfeeding and how to access help with infant problems such as feeding, crying and sleep disruptions, which are typically the most problematic for parents, especially for their first child. Parents often use the antenatal visit to seek guidance on conditions such as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). The prevalence of SIDS has shown a dramatic, worldwide reduction, which, to some extent, is directly related to antenatal guidance, and campaigns urging parents to place their infants in a supine, or back-lying position while sleeping (AIHW 2008; Child and Youth Mortality Review Committee 2008).

Childbirth

For Indigenous mothers, the antenatal period and birth hold unique challenges, especially for those who live in rural and remote areas. Compared with non-Indigenous mothers, ATSI mothers have more births (2.4 in their lifetime) than non-Indigenous Australian mothers (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). Many are younger when they give birth and, if they attend antenatal classes, it is usually at a later stage of pregnancy and less frequently than non-Indigenous women. Teenage pregnancy is also more prevalent in Indigenous women (19%), compared with non-Indigenous mothers (4%). Indigenous neonatal deaths occur more frequently, and Indigenous babies are twice as likely to be low birth-weight, especially if they have not attended antenatal care (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). Maternal deaths are also much higher for Indigenous women, and many encounter a lack of culturally appropriate birth practices in the Australian health care system. The cultural preference of many Indigenous women is to have ‘birth on country’, which is a cultural rite of passage at childbirth, where women’s identity and connections with the land and country are transferred, shared and celebrated (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). A number of culturally appropriate models of this type of birthing exist throughout Australia, mostly run by women in the local community, but these are limited to certain geographical areas.

The cultural elements of birth are significant to many Indigenous women, providing important links to culture and the land.

For most mothers and their partners, childbirth is a joyous occasion, but there are also risks to health. These can include injuries to the vaginal canal, temporary anaemia due to blood loss and, for some mothers, dramatic changes in their emotional state. Another issue is the risk of infection from a surgical birth. This is a growing problem, with the rates of caesarean section increasing worldwide. The WHO (2005) guideline recommends a maximum proportion of 15% for caesarean sections compared with vaginal births, however the rate of caesarean births in many countries exceeds this proportion (Althabe and Belizan, 2006, Anderson, 2004 and Moore, 2005). In Australia the national rate is around 30%, and states such as Western Australia have recorded a rate of 33.9%, which has been rising annually (Gee et al 2007). In New Zealand the rate is 23.7% (MOHNZ 2008a). The rate of inductions at birth has also increased worldwide to 25–30% of births (MacKenzie 2006). This creates a set of other risks related to epidural analgesia, and morbidity such as birth injury and lengthened hospital stay (MacKenzie 2006).

Postnatal depression

One of the most serious challenges for many women at the time of childbirth is related to the emotional aspects of the experience. Postnatally, many women experience being a bit down for various lengths of time, and this may reflect a depressed mood or tiredness that can begin prior to the birth (Figueiredo et al., 2009 and Seimyr et al., 2009). For some mothers, their emotional state evolves into the more serious problem of postnatal depression. Postnatal depression is reported to occur at a rate close to the rate of other types of depression in the population, in approximately 13% of mothers (Dennis et al., 2009 and Hewitt and Gilbody, 2009). O’Brien et al (2008) found in their study of women birthing in two Australian hospitals, an unexpected rate of 44% of postnatal distress. Postnatal distress and depression have been linked to feelings of social isolation and lacking an intimate confidant or friend after the birth (Dennis et al 2009). Postnatal depression tends to develop in the first few months after the baby is born, with a peak in incidence at around 4–6 weeks (Hewitt & Gilbody 2009). Some of the factors contributing to postnatal depression are listed in Box 6.2.

BOX 6.2

Point to ponder

Point to ponder

• Unwanted or stressful pregnancy.

• Poor relationship with the child’s father or other family members.

• Criticism or lack of social support, either from family members or peers.

• Poverty and the social conditions it precipitates, such as crowding, substandard housing or unemployment.

• Being a migrant mother without a support network.

• Prior psychiatric problems or a history of depression.

• Stressful life events.

• Sleep deprivation or anxiety.

• Having an infant born with a medical problem or not surviving the birth.

• Poor physical health or coincidental adverse life events, such as the loss of a partner.

• Being depressed prior to birth.

• Having a depressed partner.

(Dennis et al 2009; Figueiredo et al 2009; WHO 2005)

Given widespread recognition of the significance of postnatal depression, the past decade has seen a burgeoning body of research into the condition. Studies have shown that it is the most common form of maternal morbidity after delivery, with health consequences for the infant and the woman’s partner as well as herself (Dennis et al 2009). Infants and children are particularly vulnerable because of the impairment to maternal–infant interactions, which can cause attachment insecurity, developmental delay, and social and interaction difficulties. Researchers have found that less than 50% of postnatal depression cases are detected by health care professionals, which indicates the need to screen all new mothers for the condition (Hewitt & Gilbody 2009). Treating the condition with antidepressants is not always appropriate, particularly for breastfeeding mothers (Morrell et al 2009). Several studies, including a Cochrane systematic review, have shown that postnatal depression can be treated effectively with psychosocial and psychological techniques (Dennis et al 2009).

Postnatal depression is a significant challenge for many women in Australia and New Zealand. It can have profound implications for the health of both mother and child.

Another study, that trialled a telephone-based peer support program by volunteer mothers over 12 weeks’ postpartum, showed that this type of support reduced the incidence by half among those at risk of postpartum depression (Dennis et al 2009). The researchers concluded that telephone support is ideal for this purpose, given that it is flexible, private and non-stigmatising, and it overcomes the problems of accessibility to services, especially for mothers of low SES. Another trial of social support by health visitors in the UK that provided weekly one-hour sessions with new mothers for up to 8 weeks, also demonstrated dramatic reductions in the incidence of postpartum depression (Morrell et al 2009).

Men may also experience the effects of depression in the postnatal period. This depression is closely associated with maternal depressive symptoms and previous paternal depression (Ramchandani et al 2008) and has been demonstrated to place children at increased risk of emotional and behavioural problems (Schumacher et al., 2008 and Ramchandani et al., 2008). Nurses and midwives must be aware of the signs and symptoms of depression among men in the early postpartum period and consider screening men for depression where indicated — particularly where the mother is experiencing depression (Schumacher et al., 2008 and Ramchandani et al., 2008). There is some evidence that including fathers in antenatal preparation results in an increased awareness of the maternal experience and it has been suggested that father-specific sessions may be helpful in preparing men for the transition to fatherhood (Schumacher et al 2008).

Children’s psychosocial wellbeing

Measurements of mental health and wellbeing among Australian children are imprecise because of a lack of national data. However, it is likely that the rate of mental illness is likely to be similar to other OECD countries, with a prevalence of around 20% of children. In New Zealand, it is estimated that 17.6% of children under the age of 11 have some type of mental health problem with up to 5% suffering from conduct disorder (WHO 2009a; Craig et al 2007). In the US, it is estimated that one in 10 children suffers from an emotional disturbance severe enough to cause impairment (Herman et al 2009). Data from general practice have recorded rates of mental illness in children that include behaviour symptom/complaint (27%), ADHD (18%), sleep disturbance (14%) and depression/anxiety disorder (13%) (AIHW 2009a). Children with these complaints are disadvantaged not only from the disease, but also socially, in terms of stigma, discrimination, functional impairment and the risk of premature death (AIHW 2009a). Childhood depression is thought to be a significant issue for many children, overlooked, untreated and, in many cases, debilitating (Herman et al 2009). The mental health of immigrant children is a particular concern, especially those who are refugees and/or are living in detention centres awaiting status decisions. This affects approximately 1% of Australian children, who are refugees from war-torn countries. Most arrived through the government’s Humanitarian Program and many live in relative socio-economic disadvantage (AIHW 2009a).

Children’s psychosocial wellbeing is becoming an increasingly important determinant of health.

Mental ill health

Although mental illness may arise from birth it is also a product of social determinants within the family and the child’s psychosocial world. Having a parent with mental illness can predispose a child to mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or depression, however these conditions may not develop without the interaction of non-genetic risk factors. Other precipitating factors include slow academic achievement, physical or psychological trauma, abuse and/or neglect, loss of family, or community and cultural factors, such as having low SES or being discriminated against (AIHW 2009a). Having a child with a mental illness is also traumatic for parents, who may suffer high levels of distress and depression that can lead to a vicious circle of stress and emotional ill health for all family members (Scharer et al 2009). For children from economically deprived families the presence of mental ill health may be both a cause and consequence, as economically deprived children have a high risk of behavioural or emotional problems that can manifest in childhood and persist into adult life.

Learning readiness and social development

Economic disadvantage in childhood is also linked to learning readiness, and this is an area that is attracting considerable research attention. Early learning enhances a child’s functioning, including language development, literacy acquisition, cognitive processes, emotional development, self-regulation and problem-solving skills (Zubrick et al 2008). As a child makes the all-important transition to school, academic competence is important to him/her developing the ability to process feedback from the family, school and peer environment. Support through this transition can help children gain both cognitive and social competence. However, if the child encounters criticism or a harsh learning environment this may be more difficult, especially if the child has some emotional disadvantage on entry to school (Herman et al., 2009 and Zubrick et al., 2008).

The preschool experience is critical to children developing the skills for lifelong learning, particularly in learning to read, as studies have found a link between reading problems in children and depressive illness (Herman et al 2009). With a large proportion of parents working outside the home, the quality of child care plays an important role in helping children develop a sense of belonging and the competence, independence and the community connectedness they require to grow into successful adults. Preschool and child care can help young children develop cognitive and social skills that prepare them for the transition to school, which can be a significant asset for children from low socio-economic environments (AIHW 2009a). This is achieved through positive adult–child interactions and regular opportunities for guided play with other children, which focus on early sensory and language development as well as a child’s socialisation skills.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access