Chapter 7. Healthy adolescents

Introduction

Adolescents are predominantly physically healthy. It is the social aspects of life as an adolescent that present the greatest challenge for achieving health and wellbeing.

The adolescent journey is sometimes described as fraught with confusion, conflict and risk. However, an alternative view sees adolescents ‘at promise’ instead of ‘at risk’. When the family, school, neighbourhood and community lend timely, sensitive and appropriate support for their lives, they can indeed be at promise of creating a healthy future. On the other hand, if the social determinants embedded in the family, school, neighbourhood and community fail to provide a web of support for their transitions, there is a greater risk that they will begin their adult lives at a disadvantage. As a result, they may be confronted with compromised health status, failure to thrive, less than optimal resilience and fewer opportunities to add value to each step of the journey.

Adolescence is the most critical, the most interesting and the most tortuous stage on the journey to adulthood. In the early years of adolescent life, and later, in a stage of pre-adulthood, significant habits of mind and action are formed. These thoughts, attitudes and behaviours can mean the difference between health and ill health, confidence or low self-esteem, joy or depression, social competence and vitality, or isolation in later life. Many researchers of adolescent behaviours and attitudes write about risk and risk factors. But a strengths-based approach to analysing adolescent life would see each transition along the pathway to adulthood in terms of potential and possibilities. From this perspective, each challenge offers an opportunity to develop inner resourcefulness. This can be accomplished with the support of family, school and the social environment, each of which plays a critical role in connecting the various elements of adolescent life with one another.

As health professionals we are particularly interested in the journey as well as the outcome. Some of the main issues we’ll address in this chapter include questioning what distinguishes the adolescent who progresses through the tortuous path to healthy adulthood from others who fall victim to high-risk behaviours. What sustains behaviours such as smoking, overeating, abusing alcohol or other harmful substances, unsafe sexual activities and self-inflicted injury beyond the stage of experimentation? Why are some young people better able to change the course of their life midstream and redirect their efforts towards a healthier future? How have some adolescents been successful, while others with seemingly similar backgrounds have slipped backwards into the abyss of unhealthy lifestyles? How are some young people able to face adversity and bounce back stronger for the challenge, while others become depressed and anxious? This chapter unpacks some of the evolving knowledge base underpinning adolescent life,

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 identify the factors influencing healthy adolescence

2 explain the social ecology of adolescent life

3 analyse the research evidence related to the role of family support in influencing adolescent health and wellbeing

4 identify goals for supporting and sustaining adolescents at promise

5 explain how a primary health care framework can be used in planning strategies for adolescent health

6 identify strengths and gaps in the research evidence base for working with adolescents.

The development of social competence

Adolescence is a period of rapid cognitive, psychological, social, emotional and physical changes in a person’s life (Halpern-Felsher 2009). During adolescence young people establish caring, meaningful relationships. They also seek acceptance and belonging in social groups, and this helps them develop a capacity for interpersonal intimacy (Whitlock et al 2006). These social connections are developmental and they contribute to the important tasks of identity formation and the development of autonomy and independent thinking. Sculpting out an adult identity takes precedence over any other issue, as young people ‘try on’ a range of identities to establish a sense of themselves in relation to the world and various groups of people (Erikson 1963). Identity formation is a significant step in developing critical thinking ability. Some young people find this difficult, particularly when they are balancing personal changes and aspirations with the influence of family and friends. Peers and other social groups provide a mirror within which adolescents view themselves, which can be embarrassing or empowering in their struggle for self-identity and the formation of unique ideas (Price 2009).

Identity formation is a key milestone for young people.

Without ongoing support from peer groups, families, schools and others within their social and cultural environments, some adolescents are easily led into patterns of behaviour that leave them feeling isolated, abandoned and without positive role models for successful development (Bronfenbrenner 1986). This illustrates the importance of a social ecological perspective of adolescent life. Everything is connected to everything else in their social world. Family, school, peers and the many contexts in which they interact all have an effect on one another. This includes their virtual social lives on the internet and other electronic media as well as the face-to-face interactions that frame the development of social competence. Positive role models in the home and school environment can help guide adolescents towards behaviours that help them navigate through the changes with a sense of comfort in their identity and relationships.

Family structure has an important influence on adolescent development. Many years ago young people had clear rites of passage from childhood to adult, spouse, parent and worker. In the 21st century, adolescents experience variable transitions in the public eye, which take place over an extended period of time. As we reported in Chapter 5, family structures have changed. Gone are the family norms where a father transferred to his son the means to a livelihood, and a mother passed her skills on to her daughter for a predetermined role as wife or mother. Today, many young people who grow up in families without two biological parents tend to see themselves as adults at a younger stage than those from intact families (Benson & Kirkpatrick Johnson 2009). This often results from having assumed a variety of roles in different family structures, households and family groupings. Family processes are also instrumental in influencing adolescent identity formation. These influences arise from the style of parenting (authoritarian, authoritative or permissive), and the extent to which parents exert social control and monitoring, warmth and closeness, a sense of responsibility and a clear sense of the adolescent’s place in the hierarchy of family relations (Benson & Kirkpatrick Johnson 2009).

Positive role models support young people as they develop social competence.

Social determinants of adolescent health, risk and potential

The social ecology of adolescent development can be seen as a matrix of inter-related factors that influence adolescents’ health and wellbeing. As with other population groups, the social determinants of their lives present strengths, weaknesses, threats and opportunities. The main strength of adolescents is that most tend to be physically well. The weaknesses or risks inherent in adolescent life generally revolve around the fact that, because they are in the formative stages of development, most adolescents are not yet able to take control of their lives or health-related decisions. However, good physical health is not always accompanied by good mental health. Identity formation and other psychosocial challenges place inordinate pressures on adolescents, which can pose threats to mental health. So although health status indicators may suggest that adolescents are among the healthiest groups in the population, their greatest threat to health lies in emotional, social and behavioural conditions of their lives that affect mental health (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008 and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2002).

The most conspicuous mental health issues for adolescents include the risk of depression, behavioural problems such as aggression or self-harm, adolescent pregnancy, substance misuse, sexually transmitted infections, eating disorders and obesity (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008, Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2002 and World Health Organization (WHO), 2009). Many of these are inter-related. Approximately 10% of Australian adolescents suffer from a long-term mental or behavioural problem (AIHW 2008). In New Zealand, it is estimated that 22% of 15-year-olds and 36.6% of 18-year-olds have a mental health problem (Craig et al 2007). The most serious of these, requiring hospitalisation, are substance use and schizophrenia for adolescent males, and depressive episodes, eating disorders and self-harm for adolescent girls.

Adolescent deaths are primarily caused by injuries, many of which are also related to behaviours, with a strong link between alcohol consumption, substance abuse, attempted suicide and motor vehicle accidents. Adolescents are also at risk of conditions such as asthma, cancers such as leukaemia and skin cancer (melanoma). However, these are overshadowed by the problems created by binge drinking and illicit drug use, which can also be linked to unsafe sexual behaviours and the possibility of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and adolescent pregnancy (AIHW 2008; Craig et al 2007). The most important social determinants affecting successful navigation through these conditions are family, school and social support.

Common health issues for young people include depression, pregnancy, substance abuse, STIs and obesity.

Identity and body image: weight management and eating disorders

The quality of family life has been shown to be the most powerful influence on adolescent health, particularly in relation to nutrition and weight management, which continues to be a problem for adolescents. Around 20–22% of Australian and New Zealand adolescents are overweight, with 7–9% being classified as obese (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008 and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2006). These problems are much greater for Indigenous adolescents in both countries (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008 and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2006). This creates risks for cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer in adult life, particularly when the risk is compounded by physical inactivity. Only a third of females and 46% of males participate in physical activity to the level recommended in Australian national guidelines (AIHW 2008). In New Zealand, young men aged 15–24 years are 1.5 times more likely to participate in physical activity five or more times per week than young women of the same age (MOHNZ 2008). Because overweight adolescents tend to become overweight adults, there is a strong belief that late childhood is the time to address unhealthy eating behaviours and optimal patterns of eating and activity. This is an important and complex challenge for health promotion interventions, given the known links between overweight, low self-esteem, stress, a lack of social support and the ultimate risk of depressive illness (Martyn-Nemeth et al 2009).

What’s your opinion?

What socio-ecological factors influence the discrepancy between young men and young women’s participation in physical activity?

There is a strong link between eating behaviours, stress and coping. Adolescents’ coping strategies evolve throughout the period of adolescence, as puberty poses its own set of stressors. These include physical and hormonal changes which do not always follow a predictable path. Coinciding with the increase in the number and type of stressors, physical activity levels often decline throughout this period, especially for girls (Thunfors et al 2009). In many cases, parental work schedules reduce adults’ control over mealtimes, and this can lead to poor eating habits among their children (Jui-Han & Miller 2009). In urban areas, adolescents also tend to gravitate to fast-food outlets as a place for socialising, and often substitute high salt, high sugar content foods for healthy meals at home with the family. Using food as a coping mechanism or developing fast-food habits can lead to overeating as a long-term pattern, especially if there is a lack of family and social support to buffer the effects of stress. This, in turn, can lead to lower self-esteem and depressive mood, which creates a cycle of overeating and weight problems (Martyn-Nemeth et al 2009). Although rural youth do not have the same access to fast-food outlets, many eat because they are bored, feeling emotional or depressed, or because their friends are eating (Bourke et al 2009). The need to feel connected with peers can be a potent force in eating behaviours, and a way of feeling included in group activities.

Equally as difficult is the challenge of supporting adolescents with eating disorders. For some young people, disordered eating patterns may be due to individual and cultural factors that lead to a distortion of body image (DeLeel et al 2009). To some extent, the media contributes to the prevalence of eating disorders, by reinforcing unrealistic images of what constitutes an ideal body. Images of ultra-thin models and pop stars surround adolescent life, making them difficult to ignore. In the absence of positive role models, young people may adopt a view of their ideal self based on what they see in magazines and the media instead of what is feasible.

The desire to ‘fit in’ with the group can lead to poor eating behaviours among adolescents.

The most common eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia and binge eating. Those with anorexia are thought to be obsessed with three forms of control: over their eating, their body weight and their food. This causes them to self-induce starvation out of fear of gaining weight (Ramjan 2004). Control issues may also lie at the core of bulimia and binge-eating disorders. In all three types of disorders, the young person may have an obsession with beauty or physical attractiveness, competitiveness and a desire to punish themselves as well as control their weight (Fairburn & Harrison 2003). Eating disorders are often accompanied by symptoms of depression and anxiety, irritability, mood swings, impaired concentration and a loss of sexual appetite, all of which begins a cycle of social withdrawal and isolation (Fairburn & Harrison 2003). In addition, they suffer from poor physical health, especially oral health and gastrointestinal disorders, which are related to inadequate nutritional status and/or purging after meals.

Eating disorders and family life

Although there may be many different factors involved, researchers have linked conditions such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia with family conflicts and parenting styles. The risks of these conditions are heightened when parents are too controlling, where their relationships with their adolescents are lacking in intimacy, and when they communicate inconsistent and irrational messages in relation to weight control (May et al 2006). Links have also been found between bulimia and low levels of maternal nurturance or responsiveness from family members (May et al 2006). Family meals have also been shown to have a profound effect on young people’s eating patterns. Families who place high importance on regular family meals tend to have children with less disordered eating (Fulkerson et al 2006). This seems to be related to two factors: role-modelling healthy eating and promoting family cohesion (Rodgers & Chabrol 2009). Positive role modelling establishes good nutritional habits that tend to endure throughout adult life. On the other hand, teasing, parental dieting, restricting food or commenting on the beauty standards of media personalities can lead children to disordered eating. This is a particular problem among young girls who are often susceptible to parental body image attitudes, and are made vulnerable because of their own anxieties (Rodgers & Chabrol 2009).

Family attitudes and behaviour towards eating can have a profound influence on young people’s eating habits.

Family mealtimes can promote family cohesion through meaningful communication (Franko et al 2008). Because family meals have become victim to the hurried lifestyles of many dual-earner families, researchers have turned their attention to mealtime as a vehicle for family harmony. Research linking regular family meals with a cluster of risky adolescent behaviours has found that girls reporting more frequent family meals showed reduced substance use, higher school marks, fewer depressive symptoms, decreased risk of suicide attempts and less extreme weight control behaviours (Franko et al 2008). This is thought to arise from the closeness and enjoyment of regular meals (Franko et al 2008). Parental conversations can also provide important lessons on how they solve everyday problems and deal with social pressures. Family mealtime conversations also provide opportunities for parental monitoring of adolescents’ views and behaviours (Franko et al 2008). In addition, parents’ use of alcohol at mealtimes can also have a major influence on alcohol consumption among adolescents. The combination of role modelling and family connectedness can be a vehicle for ensuring the lines of communication between parents and their adolescent children remain open. This helps establish a pattern for open and ongoing discussion of expectations and family standards (Haegerich and Tolan, 2008 and Velleman and Templeton, 2007).

Risky sexual behaviours

Sexual risk-taking is one of a number of behaviours that underline the importance of decision-making in an adolescent’s social development (Atkins and Hart, 2008 and Halpern-Felsher, 2009). Unprotected sexual activity creates a risk for unwanted pregnancy and STIs such as Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis, genital warts (HPV) and HIV, as well as cervical and anal cancers (AIHW 2008). The risk of these outcomes increases with sex at an early age and the number of sexual partners (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008, Craig et al., 2007 and Denny-Smith et al., 2006). In Australia, the median age of first sexual intercourse has been estimated at 16, but it is decreasing (Williams & Davidson 2004). This is cause for alarm, as younger sexual debut creates a higher risk of unintentional pregnancy as well as STIs. A New Zealand survey of high-school students found that 15% of sexually active students either don’t use or only sometimes use condoms and/or other forms of contraception (Adolescent Health Research Group 2008).

The problem of STIs is a particularly serious public health issue, and these infections have been increasing in Australia and New Zealand over the past decade. The incidence of HIV/AIDS is not increasing as rapidly as in the past, but many more people are now living with HIV/AIDS in the community (Nakhaee et al 2009). The personal impact on health from STIs can be severe, particularly if the infection is not detected immediately. For example, Chlamydia can be asymptomatic for a long period of time, and also increase the risk of HIV, which is a significant risk for older adolescents (Major-Wilson et al 2008). Many Chlamydial infections also progress to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), which can lead to infertility (AIHW 2008). New Zealand has the dubious distinction of being named the ‘ Chlamydia capital of the world’ with regional laboratory rates consistently higher than in Australia, the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) (Braun 2008).

Adolescent pregnancy is an ongoing concern in Australia and New Zealand, where, even though rates are declining, there remain high rates of adolescent conception compared to other OECD countries (AIHW 2009; Pinkleton et al., 2008 and Williams and Davidson, 2004).

Rates of STIs among young people remain high, with reports of variable condom usage.

In Australia, adolescent pregnancy occurs across the socio-economic spectrum and across all cultural groups, with the highest rates among Indigenous adolescents (Williams & Davidson 2004). In some Indigenous groups, this may be linked to traditional perspectives, where pregnancy and fertility are perceived as valued in their culture (DeVries et al 2009). In New Zealand, adolescent pregnancy is highest among young Maori and Pacific women and those living in the most economically deprived areas (Craig et al 2007).

The level of adolescents’ knowledge about pregnancy and STIs is a cause for concern. One study of 500 adolescents in the US found that a large majority believed that birth control pills were a form of protection against STIs. More than two-thirds thought douching protected them from STIs, and 84% believed they were having safe sex if they confined their activities to one partner (Denny-Smith et al 2006). Even nursing students have been found to have misconceptions about sexual behaviour, leading researchers to conclude that risk factor screening for pregnancy and STIs is a vital aspect of health promotion (Denny-Smith et al 2006). Clearly, a lack of knowledge about the impact of unsafe sexual behaviour is a major concern. So too, is the fact that adolescent mothers have a higher level of risk for other behaviours such as alcohol and substance abuse, impoverishment, depression and other forms of social disadvantage. These conditions can compromise the young woman’s health and wellbeing and create a greater likelihood of impediments to her future potential.

As we mentioned in Chapter 6, there are also negative outcomes for the child of an adolescent mother, as these mothers often fail to seek antenatal care. Adolescent mothers are disproportionately at risk of miscarriage, pre-term delivery, low birth-weight babies and many other complications of pregnancy that can affect their children (AIHW 2009). Children born to an adolescent mother who smokes tobacco or is involved in alcohol or substance abuse carry a higher risk of infection than the children of older parents. They are also more likely to be trapped in an intergenerational cycle of disadvantage themselves, be deprived of strong supportive networks or educational attainment, and girls often become adolescent mothers themselves (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2009 and Haldre et al., 2009).

Adolescent mothers are at disproportionate risk of miscarriage, pre-term delivery and low birth-weight infants.

So why are younger adolescents having sex? Some believe it may be linked to cultural traditions, poor parent–child relationships, use of alcohol or marijuana, or a lack of personal skills at negotiating sexual behaviour (DeVries et al 2009). For some time, public speculation has also suggested a link between the highly sexualised images in the media and early sexual activities. Research studies have now confirmed this, demonstrating that sexual content in television programs is in fact, a precipitating factor in risky sexual behaviours. One study of adolescent pregnancy in the US found that those with high levels of exposure to sexual media content were twice as likely as others to experience pregnancy in the next three years (Chandra et al 2008). The influence of media images also reflects the importance of peer group norms. An Australian study of adolescents’ perceptions of peer sexual attitudes and behaviours revealed that they overestimated the extent to which their peers were sexually active (Lim et al 2009). The researchers concluded that this could induce young people to alter their behaviours in ways that could promote early onset of sexual activity or increase the risks of unsafe sexual practices, especially related to condom use (Lim et al 2009).

High levels of sexual content in the media is a precipitating factor for risky sexual behaviour among young people.

A number of researchers have focused on the reasons adolescents shy away from using contraception to prevent STIs and pregnancy. Sheeder et al (2009:302) contend that most adolescents ‘are not cognitively and psychosocially mature enough to form intimate, mutually respectful, long-term interpersonal relationships’. Their sexual decisions are made in the moment, intuitively, based on romantic circumstances rather than rational thought. They have no prior experience of what it is like to bear a child, and rarely see the barriers or negative aspects of conception. Many also have a lack of knowledge or misperceptions about the risk of pregnancy or how it will impinge on their future goals (Haldre et al., 2009 and Sheeder et al., 2009). This also affects her decisions about the pregnancy.

Choosing between persevering with or terminating a pregnancy is one of the most difficult issues that confront any woman, especially young adolescents. The adolescent mother’s developmental stage, her level of self-esteem and her resources have profound effects on the outcomes of pregnancy. The social and political context in which reproductive choices are made also have a major influence on choices and their outcomes. Social mores and competing views on what is morally right or wrong can conspire against her reproductive choices, creating highly inflamed debates and polarised opinions. Sometimes this is too difficult an environment for a young person to deal with in such an emotionally charged situation. Social and cultural messages that convey resilience will support young women to make appropriate choices regarding pregnancy (Sparrow 2009).

Compounding risk: alcohol, drug use and tobacco smoking

A large number of adolescents who develop STIs or have unplanned pregnancies have experienced these because of decisions that were made while they were affected by either alcohol or illicit drugs. This is concerning, because even in small amounts and infrequent episodes, overuse of these substances can be dangerous and have far-reaching effects. Although the proportion of young people drinking alcohol has declined slightly in recent times, the proportion of those who are drinking at hazardous levels and engaging in binge drinking remains high (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), 2008, ARACY, 2009 and Velleman and Templeton, 2007). This is a global phenomenon, raising concerns because it is a compromise to community life. It is estimated that 24% of young Australians drink at risky levels (ARACY 2009). In New Zealand 50% of young men and one in three young women aged 18–24 years are considered to have hazardous drinking patterns (MOHNZ 2008). In rural communities this is even higher, especially for Indigenous young people, with 70% of rural Australian adolescents more likely to die from risky drinking than those in urban areas (ARACY 2009). In rural areas, adolescents consume alcohol as a way of being socially included, as alternative social activities are often unavailable (Bourke et al 2009). Ingesting excessive amounts of alcohol or other substances can be considered a form of self-harming behaviour. Chronic excessive alcohol misuse is strongly correlated with other risks to health, including unsafe sexual activity, antisocial and criminal behaviours, injuries from motor vehicle accidents, and mental health problems (Velleman & Templeton 2007). Overuse of alcohol can also cause or exacerbate diabetes, heart disease, liver disease and a range of other threats to physical health.

Hazardous drinking patterns are common among young people, and are strongly correlated with other risks to health, such as unsafe sexual activity, criminal behaviour and motor vehicle accidents.

The most recent Australian data show that, even though consumption of alcohol has been gradually decreasing over the past 30 years, more than 60% of Australian boys aged 16–17 and 52% of girls of this age ingest alcohol weekly. This is higher than the prevalence among New Zealand adolescents, where it is estimated that close to one-third of those aged 14–17 drink alcohol weekly, 30% of whom are heavy drinkers by this time (AIHW 2008). A small proportion of Australian adolescents use ‘hard drugs’ such as methamphetamine, cocaine, ecstasy, cannabis or other illicit substances, but the prevalence of drug use is declining (AIHW 2008). This is similar to the global situation, except that cannabis smoking remains high among adolescents in some other countries, while hard drug use is declining.

Although tobacco use has been declining over the past several decades, it is an ongoing problem for many adolescents in Australia and New Zealand (AIHW 2009). Some adolescents see smoking as a way of relaxing, dealing with boredom or stress, gaining independence or controlling weight (Bourke et al 2009). Tobacco is also known to be a ‘gateway’ drug, which may lead to ingestion of alcohol, cannabis or other harmful substances. Alarmingly, one UK study found that half of those who reported ever using drugs began smoking cannabis at age 10–15 (Velleman & Templeton 2007). Young people who try their first cigarette at the time of adolescence are at the highest risk of becoming daily smokers and they are the least likely to quit smoking (Sherman & Primack 2009). In addition, the longer-term effects of passive smoking of tobacco products are not only potentially fatal to the smoker, but compromise the health of others, including infants and young children (Hamilton 2003). For this reason, tobacco smoking is seen as the leading preventable cause of death and disease (Sherman & Primack 2009).

Young people who try their first cigarette during adolescence are at high risk of becoming daily smokers.

Adolescent risk-taking in areas such as unsafe sexual behaviour or alcohol and substance misuse, has been described as a syndrome of behaviours, wherein engaging in one type of risk makes a person prone to engage in others (Leather 2009). Some risk-taking is thrill-seeking, often aimed at participating in peer group social life. Other risky behaviours are a form of rebellious, reckless or antisocial acts (Leather 2009). Some see adolescent risk-taking as a natural part of development, a type of adolescent play, while others link risky behaviours to the notion of invulnerability, a feeling among adolescents that they are invincible (Leather 2009). Despite these perspectives, it is not always helpful to stereotype reasons for risk-taking given individual differences (Holland & Klaczynski 2009). What all researchers and scholars of adolescent life agree on is that for some clusters of risky behaviours, there are serious and enduring psychological and social repercussions. These can include threats to mental health, which are manifest in depression, suicide ideation, low self-esteem, poor body image, low social connectedness, a lack of academic performance at school and a poor quality of family life (Holland & Klaczynski 2009).

Depression, self-harm and suicide

The psychosocial conditions of adolescents’ lives and their behavioural decisions can lead to depression, self-harm and in some cases, suicide. They can also result in some adolescents being subjected to violence, bullying at school and adopting a lifestyle that is detrimental to health. In the 21st century, depression is considered the leading cause of disability throughout the world, affecting 15–20% of adolescents (Herman et al 2009). The prevalence of depression varies with age and gender, with a higher incidence among girls (AIHW 2008). The social determinants of depression include family factors, such as having a parent who is mentally ill (Hayman 2009). Other factors include the interactive relationship between parent and child, and a variety of stressors that lie within a young person’s physical, social and cultural context. For adolescents, these are usually their school and peer relationships, however parental work schedules that prevent family closeness have also been linked to the development of adolescent depression (Jui-Han & Miller 2009).

Depression has an impact on every aspect of an adolescent’s life and can have dire consequences, including suicide, which is the leading cause of death among adolescents (Herman et al 2009). Major depressive disorder (MDD), or clinical depression, is a state of mental ill health where the emotional lows, often described as sadness, become pervasive (Herman et al 2009). Besides genetic factors, depression can be the result of an accumulation of stressful life events involving threat, loss, humiliation or personal defeat (Commonwealth of Australia 2008). Clinical depression is often confused with the wide-ranging mood swings and intense emotional highs and lows young people often experience during their adolescent years. These mood swings are a normal part of learning to respond to events and other people. However, some events and interactions with others can cause dramatic shifts in emotions that aren’t quickly resolved. If these negative responses continue for a long period of time, it may be a sign that the person is slipping into a depressed state. Instead of bouncing back from a reaction or negative mood, the person may continue on a downward slide, often isolating him/herself from others. Depression can be experienced differently by different individuals. It can make a person feel miserable or irritable most of the time. Some feel restless or agitated, while others feel down and tired all the time. Concentration may be difficult, and they can lose interest in their usual activities, overlook school or work responsibilities, and experience changes in their relationships with family members. They may be overcome by feelings of guilt or worthlessness and ultimately decide life is not worth living (Online. Available: www.youthbeyondblue.com [accessed 4 November 2009]).

ACTION POINT

Depression affects 15–20% of adolescents worldwide. Health professionals must undertake comprehensive health assessments when in contact with young people in order to detect signs and symptoms of depression.

One outcome of a depressed state can be self-harming behaviours. Self-harm or deliberate self-injury is often a repetitive act of cutting, carving or burning various parts of the body, pulling out clumps of hair or overdosing on over-the-counter drugs, the latter of which is not typically a suicide attempt (Gardner 2008). In a recent New Zealand survey, 25% of female high-school students and 16% of males reported self-harm (Adolescent Health Research Group 2008). Some self-harming adolescents report that they do so to escape deep distress, hopelessness and misery, to deal with anger and frustration, or to gain relief from inner tension and conflict, or punish others or themselves. Others report that it is a way of gaining control or feeling alive (Gardner 2008). Self-harm can also be the response of someone with a psychiatric disorder or intellectual disability who is not able to express emotions verbally (Commonwealth of Australia 2008).

Self-harm is rapidly increasing among adolescents and some researchers have questioned whether this is because it is so visible in the mass media. Like substance misuse and other negative aspects of youth culture, publicity about the condition on the internet and in the press may be providing an available emotional outlet for those who are predisposed to self-harm (Velleman and Templeton, 2007 and Whitlock et al., 2006). The presence of self-harming behaviours is understandably perplexing to parents (Rissanen et al 2009). Many feel guilt and shame, searching for meaning and understanding in their own lives to make sense of the behaviour. An Australian study of mothers of self-harming adolescents reported that they felt overwhelmed by their child’s behaviour, and inadequate in their parenting skills (McDonald et al 2007). This made them feel isolated, ashamed and embarrassed, wondering what circumstances in their own lives led their child to self-harm (McDonald et al 2007).

The relationship between self-harm and suicide is complex. Unfortunately, some self-harm behaviours result in unintentional suicide before the young person has been able to receive assistance for the underlying cause of their distress (Norman 2009). The risk for suicide is up to three times greater among those who turn to alcohol, particularly binge drinking, which has been identified as the key differentiating factor in planned and unplanned suicide attempts (Schilling et al 2009). In some cases a self-harming adolescent will progress to suicide because they have resisted disclosing their feelings for fear of becoming stigmatised (Norman 2009). This makes assessment of the problem difficult for everyone in the young person’s web of influence. For parents, teachers, school nurses and other health professionals, the challenge lies in the fact that each person’s experience of stress is highly individual. The causes and extent of the self-harm are variable, and it is extremely difficult to judge which self-harming individuals will progress to the stage where suicide is attempted or completed. Some of the potential causes of self-harm are listed in Box 7.1.

BOX 7.1

• Mental illness such as depression or borderline personality disorder.

• Being the victim or perpetrator of bullying at school.

• Problems with parents.

• Stress surrounding academic performance.

• Hypersensitivity, loneliness.

• Alcohol or substance abuse.

• Family separation and divorce.

• Bereavement.

• Unwanted pregnancy.

• Experiences of abuse.

• Problems related to sexuality.

• Problems linked to race, culture or religion.

• Low self-esteem.

• Fears of being rejected.

(Mental Health Foundation 2006; Rissanen 2009)

Recognising the risk of suicide

The treatment for depression typically involves drug therapy and psychological interventions, such as counselling and behavioural therapies. Group programs that provide mutual support and focus on developing life skills can also be effective (Hayman 2009). However, for some, an unknown combination of factors conspires against recovery and there is a danger of lapsing into hopelessness. An attempt at suicide can be the result of a long history of mental illness or distress, or an impulsive or irrational act (Commonwealth of Australia 2008).

The risk of suicide among young people experiencing depression is high. It is important to recognise the warning signs of an impending suicide attempt.

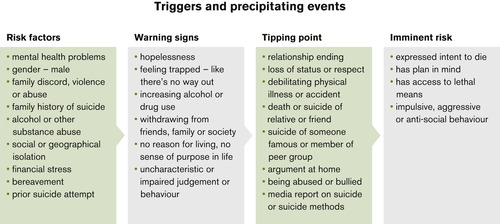

Over the past three decades the rates of suicide have declined, with some attributing this to the increased use of antidepressant medications, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), among adolescents (Bursztein & Apter 2008). For those who do attempt suicide there are usually some warning signs that signal their intention. These can include comments about suicide or death, expressions of hopelessness, rage, anger, revenge, or comments that they feel there’s no way out of the present state. The person may also begin withdrawing from friends or family, or experience abnormal anxiety, agitation or sleep disturbances, either not sleeping or sleeping all the time. They may begin consuming alcohol or other drugs. In some cases, they may begin to give away possessions, say goodbye to people close to them, or make actual threats that they are planning to commit suicide (Commonwealth of Australia 2008).

The ‘tipping point’ in deciding to commit suicide can be an argument with someone close, a relationship breakdown, a suicide by a family member, friend or associate, hearing a media report of a suicide, recurrence of an illness, an unexpected change in life circumstances or a traumatic event such as bullying, abuse or violence (Commonwealth of Australia 2008). In preparation for a suicide attempt, some adolescents will begin accessing suicide sites on the internet (Bursztein & Apter 2008). The most significant preventative measure for parents, teachers and health professionals is a strong understanding of the adolescent’s experiences. To activate protective factors it is important to remain close enough to read the risk factors and warning signs, and to know when it may be time to call for specialised assistance. Precipitating factors or typical triggers are outlined in Figure 7.1.

|

| Figure 7.1 (Commonwealth of Australia 2008, LIFE p 23 with permission) |

Adolescent life in the community context

To understand adolescent behaviour, Eckersley (2004) suggests it is necessary to disentangle the binary notions that characterise adult perspectives of adolescent life. In his view, we think of young people in terms of differences: between ill and well, marginalised and mainstream, the disadvantaged and the privileged, males and females. Instead, we should be studying young people’s ideas, preferences and their notions of wellbeing and potential. Researchers tend to over-generalise adolescents’ status and behaviours in population approaches that references them to too broad a group (Eckersley 2004). Scientifically measuring adolescents’ collective behaviour may not be as helpful as seeing them in the ecological context, which includes the social and environmental determinants of their individual lives. Another flaw in some existing perspectives of adolescence lies in adopting too objective a gaze, trying to understand adolescents and their health risks and potential on the basis of problem behaviours rather than strengths.

The major threats and opportunities of adolescent health are those embedded in the adolescent social culture, where interactions within their peer group can exert multiple pressures on their behaviours. As mentioned above, these behaviours can be positive or negative, helping the adolescent develop a strong sense of self or leading to certain clusters of problem behaviours (Haegerich & Tolan 2008). The social culture of young people in this century is markedly different from that of their parents. They are connected to the external world through a variety of electronic media. Their access to virtual peer groups creates a closer bond to like-minded individuals and to some whose lives are substantially different from theirs. These virtual networks are often used as benchmarks for adolescents’ lives and behaviours. As a result, young people today have enormous decision-making challenges. The implication for parents, nurses and other health professionals is to seek understanding of the social influences on adolescents by assessing their perspective on these experiences.

An ideal assessment tool to help identify young people’s needs is the HEADSSS assessment tool (Goldenring & Cohen 1988; see Appendix G). The assessment gathers information on the most common influences on an adolescent’s life at home, school and in other social environments. The tool can help nurses gain a multidimensional, yet individual perspective of adolescent life. The assessment data can be used to foster closer engagement with their world, and ultimately, strategies to help protect and nurture them through uncharted pathways. Assessment can also be collaborative, aimed at helping inform a whole-of-community approach. Teachers, administrators, parents, community members and others can encourage constructive opportunities and validate the adolescent’s ability for decision-making. This approach is most likely to help the young person develop a positive sense of self (Borders, 2009, Faulkner et al., 2009 and Waters et al., 2009).

ACTION POINT

Assessment tools such as the HEADSSS assessment (see Appendix G) can assist the health professional to assess young people’s needs.

Activities in the neighbourhood and community play an important role in a person’s sense of self. Where these are supportive they can help foster civic engagement, trust and other aspects of social capital that help young people develop the competence and character to contribute to society (Duke et al 2009). Strong connections to the broader culture through volunteer work or various forms of community involvement also help provide a strong grounding for adult life (Duke et al 2009). The combination of civic engagement, strong family relationships and a caring school environment can help young people believe they are the agents of their own destiny. Developing academic, social and physical competence in the context of supportive family, school and social environments can ultimately lead to empowerment and the self-confidence for successful adulthood.

Encouraging young people to become involved in school and community activities can help provide a strong grounding for adult life.

Adolescent life in the school context

The school plays a privileged and strategic role in adolescent development (Herman et al 2009). School offers the opportunity for peer socialisation, which can be the determining factor in adolescents’ choices of healthy behaviours (Thunfors et al 2009). The school culture can also be a training ground for empathy, which is a protective factor for antisocial and aggressive behaviours (Estevez Lopez et al 2008). Empathy, where a person can understand and imaginatively enter into another’s feelings, is also a core skill for developing appropriate friendship networks and partnerships. This helps young people develop mutually respectful relationships and reject those that are aggressive, especially when choosing a romantic partner. Teachers play a significant role in helping adolescents develop this level of social competence. Teachers who instil empathy, respect, courtesy, shared responsibility and a sense of community create a culture of reciprocal valuing, which helps prepare adolescents for adult life as workers and citizens (Estevez Lopez et al 2008). At school, bonding to others who share the goals of becoming academically competent, respectful and self-motivated reduces the likelihood of young people becoming drawn into substance abuse, smoking or other antisocial behaviours (Haegerich and Tolan, 2008 and Herman et al., 2009). School connectedness is also a predictor of later mental health, acting as a protective factor against mental illness (Herman et al., 2009 and Shochet et al., 2006).

School can be the centre point of a young person’s life. Positive school experiences may shape how a young person copes with peer group behaviours.

Many aspects of adolescent social life are centralised around school and peer group behaviours. Peer group norms and values can validate a young person’s identity or sanction certain behaviours through criticism or ostracism (Hamilton et al 2009). For example, ownership of material possessions (‘name-brand consumerism’) can convey physical attractiveness, athletic prowess and social skills to others in the peer group (Hamilton et al 2009:1528). Like adults, some students wear or carry name-brand merchandise like a badge of honour. This can define them as part of an in-group culture, or it can be difficult for those whose socio-economic status (SES) does not provide the means to access the same consumer goods. Unequal financial status and perceptions of inequality can also widen the gap between the in-groups and out-groups. In most cases, the tensions between these groups are manifest in the school context and linked to their virtual world of social networking.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access