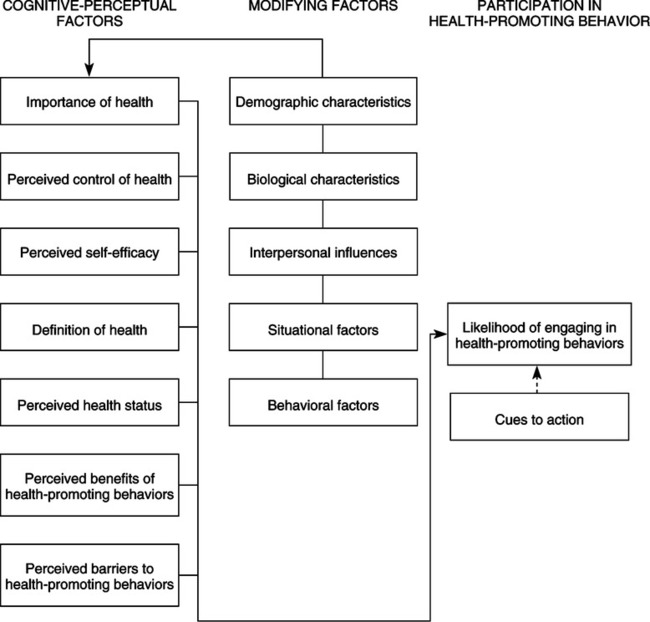

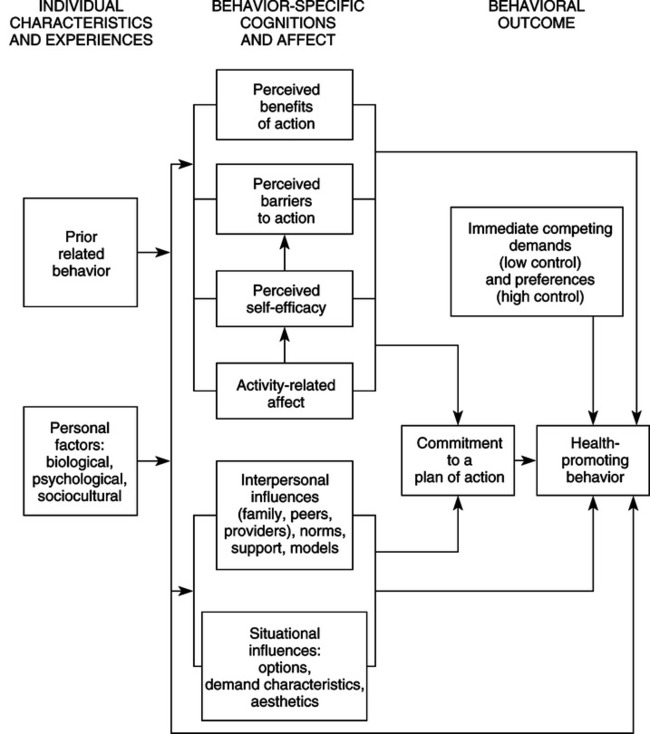

In 1964, Pender completed her baccalaureate in nursing at Michigan State University in East Lansing. She credits Helen Penhale, the assistant to the dean, for helping to streamline her program and foster her options for further education. As was common in the 1960s, Pender changed her major from nursing as she pursued her graduate degrees. She earned her master’s degree in human growth and development at Michigan State University in 1965. “The M.A. in growth and development influenced my interest in health over the human life span. This background contributed to the formation of a research program for children and adolescents,” stated Pender. She completed her PhD in psychology and education in 1969 at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Pender’s (1970) dissertation investigated developmental changes in encoding processes of short-term memory in children. Dr. Pender credits Dr. James Hall, a doctoral program advisor, with “introducing me to considerations of how people think and how a person’s thoughts motivate behavior.” Several years later, she completed master’s-level work in community health nursing at Rush University in Chicago (Pender, personal interview, May 6, 2004). After earning her PhD, Pender notes a shift in her thinking toward defining the goal of nursing care as the optimal health of the individual. A series of conversations with Dr. Beverly McElmurry at Northern Illinois University and reading High-Level Wellness by Halpert Dunn (1961) inspired expanded notions of health and nursing. Her marriage to Albert Pender, an Associate Professor of business and economics who has collaborated with his wife in writing about the economics of health care, and the birth of a son and a daughter provided increased personal motivation to learn more about optimizing human health. A study funded in 1988 by National Institutes of Health was conducted at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, Illinois, by Pender and her colleagues—Susan Walker, Karen Sechrist, and Marilyn FrankStromborg. The study tested the validity of the HPM (Pender, Walker, Sechrist, & Stromborg, 1988). An instrument, the Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile, was developed by the research team to study the health-promoting behavior of working adults, older adults, patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation, and ambulatory patients with cancer (Pender et al., 2002). Results from these studies supported the HPM (Pender, personal interview, July 19, 2000). Subsequently, more than 40 studies have tested the predictive capability of the model for health-promoting lifestyle, exercise, nutrition practices, use of hearing protection, and avoidance of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (Pender, 1996; Pender et al., 2002). Pender provided important leadership in the development of nursing research in the United States. Her work in support of the National Center for Nursing Research in the National Institutes of Health was instrumental to its formation. She has promoted scholarly activity in nursing through her involvement with Sigma Theta Tau International, as a past president of the Midwest Nursing Research Society (1985 to 1987), and as chairperson of the Cabinet on Nursing Research of the American Nurses Association. Inducted as a fellow of the American Academy of Nursing in 1981, she served as President of the Academy from 1991 until 1993 (N. Pender, curriculum vitae, 2008). In 1998, she was appointed to a 4-year term on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, an independent panel charged to evaluate scientific evidence and to make age-specific and risk-specific recommendations for clinical preventive services (Pender, 2006). A recipient of many awards and honors, Dr. Pender has served as a distinguished scholar at a number of universities. She received an honorary doctoral degree from Widener University in 1992. In 1988, she received the Distinguished Research Award from the Midwest Nursing Research Society for her contributions to research and research leadership, and in 1997, she received the American Psychological Association Award for outstanding contributions to nursing and health psychology. In 1998, the University of Michigan School of Nursing honored Pender with the Mae Edna Doyle Award for excellence in teaching (Pender, personal interview, May 24, 2004). Her widely used text, Health Promotion in Nursing Practice (Pender et al., 2002), was the American Nurses Association Book of the Year for contributions to community health nursing (Pender, 2006). Pender was the Associate Dean for Research at the University of Michigan School of Nursing from 1990 to 2001. In this position, Dr. Pender facilitated external funding of faculty research, supported emerging centers of research excellence in the School of Nursing, promoted interdisciplinary research, supported translating research into science-based practice, and linked nursing research to the formulation of health policy (Pender, 2006). A child and adolescent health behavior research center initiated at the University of Michigan in 1991 represents Pender’s efforts to build a large interdisciplinary research team to study and influence the health-promoting behaviors of individuals by understanding how these behaviors are established in youth (Pender, personal interview, May 24, 2000). Her current and future program of research has two major foci, as follows: 1. Understanding how self-efficacy effects the exertion and affective (activity-related affect) responses of adolescent girls to the physical activity challenge 2. Developing an interactive computer program as an intervention to increase physical activity among adolescent girls (Pender, 2006) Pender has published numerous articles on exercise, behavior change, and relaxation training as aspects of health promotion and has served as an editor for journals and books. Pender is recognized as a scholar, presenter, and consultant on health promotion topics. She has consulted with nurse scientists in Japan, Korea, Mexico, Thailand, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, England, New Zealand, and Chile (N. Pender, curriculum vitae 2000; Pender, 2006). Her book is now available in the Japanese and Korean languages (Pender, 1997a, 1997b). As Professor Emeritus at the University of Michigan School of Nursing, Pender is involved in influencing the nursing profession by providing leadership as a consultant to research centers and providing early scholar consultation (Pender, 2006). As a nationally and internationally known leader, Pender speaks at conferences and seminars. She collaborates with Dr. Michael O’Donnell, editor of the American Journal of Health Promotion, to advocate for legislation to fund health promotion research (Pender, personal interview, May 6, 2004). Pender’s background in nursing, human development, experimental psychology, and education led her to use a holistic nursing perspective, social psychology, and learning theory as foundations for the HPM. The HPM (Figure 21-1) integrates several constructs. Central to the HPM is the social learning theory of Albert Bandura (1977), which postulates the importance of cognitive processes in the changing of behavior. Social learning theory, now titled social cognitive theory, includes the following self-beliefs: self-attribution, self-evaluation, and self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a central construct of the HPM (Pender, 1996; Pender et al., 2002). In addition, the expectancy value model of human motivation that Feather (1982) described, which supports that behavior is rational and economical, is important to the model’s development. The HPM is similar in construction to the health belief model (Becker, 1974) but is not limited to explaining disease prevention behavior. The HPM differs from the health belief model in that the HPM does not include fear or threat as a source of motivation for health behavior. For this reason, the HPM expands to encompass behaviors for enhancing health and potentially applies across the life span (Pender, 1996; Pender et al., 2002). The HPM, as depicted in Figure 21-1, served as a framework for research aimed at predicting overall health-promoting lifestyles and specific behaviors such as exercise and use of hearing protection (Pender, 1987). Pender and colleagues have conducted a program of research funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research to evaluate the HPM in the following four populations: (1) working adults, (2) older community-dwelling adults, (3) ambulatory patients with cancer, and (4) patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. These studies tested the validity of the HPM (Pender, personal interview, May 24, 2000). A summary of findings from earlier studies is included in the 1996 edition of Health Promotion in Nursing Practice (Pender, 1996). Additional studies testing the model are discussed in the fifth edition of Health Promotion in Nursing Practice (Pender et al., 2006). The fifth edition of this text includes greater emphasis on the HPM as applied to diverse and vulnerable populations and addresses evidence-based practice. The rationale for revision of the HPM stemmed from the research studies. The process of refining the HPM, as published in 1987, led to several changes (see Figure 21-1) (Pender, 1996). First, importance of health, perceived control of health, and cues for action were deleted from the model. Second, definition of health, perceived health status, and demographic and biological characteristics were repositioned in the category of personal factors in the 1996 revision of the HPM (Pender, 1996) and are also displayed in the fourth edition of Health Promotion in Nursing Practice (Pender et al., 2002) (Figure 21-2). Finally, the revised HPM (see Figure 21-2) adds three new variables that influence the individual to engage in health-promoting behaviors (Pender, 1996): The revised HPM focuses on 10 categories of determinants of health-promoting behavior. Currently being tested empirically, the revised model identifies concepts relevant to health-promoting behaviors and facilitates the generation of testable hypotheses (Pender et al., 2002). The HPM provides a paradigm for the development of instruments. The Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile and the Exercise Benefits-Barriers Scale (EBBS) are two examples.* Both of these instruments serve to test the model and to further model development. The purpose of the Health Promotion Lifestyle Profile instrument is to measure health-promoting lifestyle (Pender, 1996). The Health Promotion Lifestyle Profile II (HPLP-II), a revision of the original instrument, is used in research.† The 52-item, four-point, Likert-styled instrument consists of the following six subscales: (1) health responsibility, (2) physical activity, (3) nutrition, (4) interpersonal relations, (5) spiritual growth, and (6) stress management. Means can be derived for each subscale, or a total mean signifying overall health-promoting lifestyle (Walker, Sechrist, & Pender, 1987). The instrument provides an assessment of a healthpromoting lifestyle of individuals that is clinically useful to nurses in patient support and education. The HPM identifies cognitive and perceptual factors as major determinants of health-promoting behavior. The EBBS measures the cognitive and perceptual factors of perceived benefits and perceived barriers to exercise (Sechrist, Walker, & Pender, 1987). The 43-item, four-point, Likert-styled instrument consists of a 29-item benefits scale and a 14-item barriers scale that may be scored separately or as a whole. The higher the overall score on the 43-item instrument, the more positively the individual perceives the benefits to exercise in relation to barriers to exercise (Sechrist et al., 1987). The EBBS provides a clinically useful means for evaluating exercise perceptions. The assumptions reflect the behavioral science perspective and emphasize the active role of the patient in managing health behaviors by modifying the environmental context. In the third edition of her book, Health Promotion in Nursing Practice, Pender (1996) states the major assumptions of the HPM as follows: 1. Persons seek to create conditions of living through which they can express their unique human health potential. 2. Persons have the capacity for reflective self-awareness, including assessment of their own competencies. 3. Persons value growth in directions viewed as positive and attempt to achieve a personally acceptable balance between change and stability. 4. Individuals seek to actively regulate their own behavior. 5. Individuals in all their biopsychosocial complexity interact with the environment, progressively transforming the environment and being transformed over time. 6. Health professionals constitute a part of the interpersonal environment, which exerts influence on persons throughout their life spans. 7. Self-initiated reconfiguration of personenvironment interactive patterns is essential to behavioral change (pp. 54–55). The model is an attempt to depict the multifaceted natures of persons interacting with the environment as they pursue health. Unlike avoidance-oriented models that rely upon fear or threat to health as motivation for health behavior, the HPM has a competence- or approach-oriented focus (Pender, 1996). Health promotion is motivated by the desire to enhance well-being and to actualize human potential (Pender, 1996). In her first book, Health Promotion in Nursing Practice, Pender (1982) asserts that complex biopsychosocial processes motivate individuals to engage in behaviors directed toward the enhancement of health. Fourteen theoretical assertions derived from the model appear in the fourth edition of the book, Health Promotion in Nursing Practice (Pender et al., 2002): 1. Prior behavior and inherited and acquired characteristics influence beliefs, affect, and enactment of health-promoting behavior. 2. Persons commit to engaging in behaviors from which they anticipate deriving personally valued benefits. 3. Perceived barriers can constrain the commitment to action, the mediator of behavior, and the actual behavior. 4. Perceived competence or self-efficacy to execute a given behavior increases the likelihood of commitment to action and actual performance of behavior. 5. Greater perceived self-efficacy results in fewer perceived barriers to specific health behavior. 6. Positive affect toward a behavior results in greater perceived self-efficacy, which, in turn, can result in increased positive affect. 7. When positive emotions or affect is associated with a behavior, the probability of commitment and action is increased. 8. Persons are more likely to commit to and engage in health-promoting behaviors when significant others model the behavior, expect the behavior to occur, and provide assistance and support to enable the behavior. 9. Families, peers, and healthcare providers are important sources of interpersonal influences that can increase or decrease commitment to and engagement in health-promoting behavior. 10. Situational influences in the external environment can increase or decrease commitment to or participation in health-promoting behavior. 11. The greater the commitment to a specific plan of action, the more likely health-promoting behaviors are to be maintained over time. 12. Commitment to a plan of action is less likely to result in the desired behavior when competing demands over which persons have little control require immediate attention. 13. Commitment to a plan of action is less likely to result in the desired behavior when other actions are more attractive and thus preferred over the target behavior. 14. Persons can modify cognitions, affect, and the interpersonal and physical environments to create incentives for health actions (pp. 63–64). Wellness as a nursing specialty has grown in prominence during the past decade. Current state-of-the-art clinical practice includes health promotion education. Nursing professionals find the HPM very relevant, because it applies across the life span and is useful in a variety of settings (Pender, 1996; Pender et al., 2002). The HPM is used widely in graduate education and is being used increasingly in undergraduate nursing education in the United States (Pender, personal interview, May 24, 2000). In the past, health promotion was placed behind illness care, because clinical education was conducted primarily in acute care settings (Pender, Baraukas, Hayman, Rice, & Anderson, 1992). Increasingly, the HPM is incorporated in nursing curricula as an aspect of health assessment, community health nursing, and wellness-focused courses (N. Pender, personal interview, May 24, 2000). Growing international efforts across a number of countries are working to integrate the HPM into nursing curricula (Pender, personal interview, May 6, 2004; Pender et al., 2002). The model continues to be refined and tested for its power to explain the relationships among factors believed to influence changes in a wide array of health behaviors. Sufficient empirical support for model variables now exists for some behaviors to warrant design and conduct of intervention studies to test model-based nursing interventions. Lusk and colleagues (Lusk, Hong, Ronis, Eakin, Kerr, & Early, 1999; Lusk, Kwee, Ronis, & Eakin, 1999) used important predictors of construction workers’ use of hearing protection from the HPM (self-efficacy, barriers, interpersonal influences, and situational influences) to develop an interactive, video-based program to increase use. This large, multiple-site study found that the intervention increased the use of worker hearing protection by 20% compared with the group without intervention—a statistically significant improvement from baseline (Lusk, Hong et al., 1999). Additional intervention studies represent the next step in the use of the model to build nursing science. The model is middle range in scope. It is highly generalizable to adult populations. The research used to derive the model was based on male, female, young, old, well, and ill samples. The research agenda includes application in a variety of settings. A research program tested the applicability of the model to children aged 10 to 16 years (Robbins, Gretebeck, Kazanis, & Pender, 2006). Cultural and diversity considerations support model testing in diverse populations. The model has been supported through testing by Pender and others as a framework for explaining health promotion. The model continues to evolve through planned programs of research. Continued empirical research, especially intervention studies, will further refine the model. The Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile has emerged as an instrument used to assess health-promoting behaviors (Pender et al., 2006).

Health Promotion Model

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS

ACCEPTANCE BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Practice

Education

FURTHER DEVELOPMENT

CRITIQUE

Simplicity

Generality

Empirical Precision

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access