CHAPTER 1 Health promotion in context

Primary Health Care and the New Public Health movement

There are many factors that influence health and illness. In this chapter the determinants of health and illness will be outlined and we will review the development of the World Health Organization’s policy process to achieve Health for All. The conceptualisations of health and illness and the responses of individuals, communities and countries are socially constructed. The role that Primary Health Care, the New Public Health movement and health promotion play in achieving the goal of Health for All will be discussed and a continuum of approaches to promote health will be introduced.

There are many terms used to describe the position of countries worldwide. Currently, the descriptors are tied to economic status such as ‘developed’ or ‘developing’. Similarly, ‘first world’ and ‘third world’ have been used for many years. ‘Developed’ countries are relatively rich and have a strong industrial base. The ‘developing’ countries are neither rich nor have a strong industrial base. In this book we will use the terms the Majority world and the Minority world because they provide a meaningful description of how the world is divided up now. The majority of the world’s people are not rich but there is a minority of people who are. The United States of America (USA) for example is a very rich and powerful country and part of a small minority in the world. Bangladesh is very poor and part of the large majority in the world. However, within both of these countries are people who belong to the Majority world and Minority world.

THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION RESPONDS TO INTERNATIONAL HEALTH PROBLEMS

the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition

the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition

the health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent upon the fullest cooperation of individuals and states

the health of all peoples is fundamental to the attainment of peace and security and is dependent upon the fullest cooperation of individuals and states

the achievement of any state in the promotion and protection of health is of value to all

the achievement of any state in the promotion and protection of health is of value to all

unequal development in different countries in the promotion of health and control of disease, especially communicable disease, is a common danger

unequal development in different countries in the promotion of health and control of disease, especially communicable disease, is a common danger

healthy development of the child is of basic importance

healthy development of the child is of basic importance

the ability to live harmoniously in a changing total environment is essential to such development

the ability to live harmoniously in a changing total environment is essential to such development

the extension to all peoples of the benefits of medical, psychological and related knowledge is essential to the fullest attainment of health

the extension to all peoples of the benefits of medical, psychological and related knowledge is essential to the fullest attainment of health

informed opinion and active cooperation on the part of the public are of the utmost importance in the improvement of the health of the people, and, finally,

informed opinion and active cooperation on the part of the public are of the utmost importance in the improvement of the health of the people, and, finally,

governments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples, which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures.

governments have a responsibility for the health of their peoples, which can be fulfilled only by the provision of adequate health and social measures.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s there was growing concern that the health status of some populations had not improved as predicted, despite the investment in and rapid growth of health care systems. Minority countries invested in high technology; however, those in Majority countries lacked access to even basic health care services. As medical technologies and medical knowledge developed, there had been the belief that these things would solve the health problems facing people around the world. It became increasingly apparent that this was not the case, and that high technology acute medical services had a limited effect on the health of populations. There was growing evidence that it was public health in its broadest sense, rather than medical care, which was responsible for most population health improvement (McKeown 1979). At the same time, there was a growing scepticism of the role and power of medicine itself and the value of medical treatment (Illich 1975). The determinants of health and illness were beginning to be acknowledged globally. Yet, few countries had acted to improve health by reducing poverty, improving housing and food availability, and stopping political oppression, despite the wide-ranging evidence that social conditions have a great impact on health. Some countries began to review their health systems and the approach to health and illness care. In Australia, for example, the Labor Government began to invest in community-controlled, community-based, multidisciplinary health services in 1973. The Lalonde Report (1974) had a significant impact in Canada and other Minority countries. In that report, health was represented as being dependent on biological, environmental and lifestyle factors and access to health systems. This was a dramatic shift away from the focus on the biological determinants of health that had dominated health sector thinking.

In 1978, the WHO and United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) held a major international conference on Primary Health Care in the former USSR. It was attended by representatives from 134 nations. The outcome of the conference was the Declaration of Alma-Ata (Appendix 1). This conference is now regarded as a critically important milestone in the promotion of world health.

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE

The principles of Primary Health Care

Three major principles stand out in the Declaration of Alma-Ata:

Equity means fairness and social justice implies a commitment to fairness. Empowerment is a process which enables people to participate in a way that improves their life and achieves social justice. These three key principles underpin all Primary Health Care activities; they will be discussed more fully in Chapter 2.

the use of socially acceptable technology

the use of socially acceptable technology

incorporation of health promotion and disease prevention strategies

incorporation of health promotion and disease prevention strategies

involvement of government departments other than health

involvement of government departments other than health

political action to achieve health, which includes cooperation between countries, a reduction of money spent on armaments in order to increase funds for Primary Health Care, and a commitment to world peace.

political action to achieve health, which includes cooperation between countries, a reduction of money spent on armaments in order to increase funds for Primary Health Care, and a commitment to world peace.

To some extent, achievement of these defining characteristics set out in the Declaration of Alma-Ata rely on nations undertaking a commitment to the first three key principles; without them other approaches will be ineffectual.

‘Health for All’ was not just an ideal, but a way of thinking about health care. The:

Each of these components of Primary Health Care is presented in the following section.

Primary Health Care as a philosophy

Selective and comprehensive Primary Health Care

The words ‘selective’ and ‘comprehensive’ are good descriptors of the different approaches to, or ways of ‘doing’, Primary Health Care. The strengths and weaknesses of each will be discussed throughout the book. Selective Primary Health Care (Walsh & Warren 1979, cited in Baum 2008) is based on the medical model of health care while comprehensive Primary Health Care is more consistent with the Primary Health Care philosophy discussed in this book. Comprehensive Primary Health Care is a developmental process that emphasises the aforementioned principles of equity, social justice and empowerment to work for social changes that impact on health and wellbeing. In comprehensive Primary Health Care, emphasis is on addressing the determinants of health; that is, the conditions that generate health and ill health. Therefore, provision of medical care is only one aspect of Primary Health Care. Selective Primary Health Care concentrates on treating illnesses. Thus, while comprehensive Primary Health Care focuses on the process of empowerment and increasing people’s control over all those influences that impact on their health, selective Primary Health Care operates in a way that assumes that medical care alone creates health and ensures that control over health is maintained by health professionals. In discussing the two perspectives, some have likened it to ‘the individual versus the system’ (Green & Raeburn 1988, in Baum 2008: 35).

Arguing for comprehensive over selective Primary Health Care is not to argue against the importance of addressing specific diseases. Selective Primary Health Care has produced important gains, such as reducing diseases through immunisation. Clearly we must address those diseases that cause human suffering and premature death. However, by only addressing those diseases, we risk perpetually attempting to address the end result of the problem instead of addressing the root causes of the diseases themselves or the social conditions that perpetuate disease and other suffering. Comprehensive Primary Health Care addresses these diseases and other issues in their social context, using a process that recognises the expertise that ordinary people have and their right to exert control over their own lives. There are differences in how Primary Health Care is implemented. Box 1.1 provides four key areas in which selective Primary Health Care compares poorly with comprehensive Primary Health Care.

BOX 1.1 Comprehensive Primary Health Care versus Selective Primary Health Care

1. By focusing on the eradication and prevention of diseases, selective Primary Health Care assumes that health is the absence of disease rather than, as in the broader WHO definition, a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing. This then locates action for health almost solely within the realms of specialists trained to treat disease.

2. Through its emphasis on those diseases and problems most likely to respond to treatment, selective Primary Health Care ignores the need to address issues of equity and social justice, which are at the root of many health problems.

3. In establishing medical interventions as the most important part of Primary Health Care, selective Primary Health Care ignores the importance of all those non-medical interventions, such as the provision of education, housing and food, which have a greater bearing on health than health services themselves.

4. Selective Primary Health Care limits the value of community development as a strategy for improving health to being a technique for increasing community compliance with medically defined solutions, rather than as a mechanism for community empowerment. It thus identifies expertise as residing with medical workers and denies the great expertise that people have with regard to their own lives and the issues that affect them.

(Source: Rifkin S, Walt G 1986 Why health improves: defining the issues concerning ‘comprehensive Primary Health Care’ and ‘selective Primary Health Care’. Social Science and Medicine. 23(6):12–13)

A good example of comprehensive Primary Health Care is the way in which some non-government organisations (NGOs) work internationally. In countries where the health sector is weak or non existent, NGOs such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) (MSF http://www.msf.org/) dispense essential drugs such as vaccines, and assist local communities with water and sanitation programs. MSF also provides training of local personnel to work with disadvantaged groups in remote health care centres and slums. MSF works at both preventing illness and treating disease by providing essential medical care, and also assists with essential infrastructure support in a socially acceptable and empowering way.

Primary Health Care as a strategy for organising health care

build on the Alma-Ata principles

build on the Alma-Ata principles

ensure universal access, community participation and inter-sectoral action

ensure universal access, community participation and inter-sectoral action

take account of broader population health issues, reflecting and reinforcing public health functions

take account of broader population health issues, reflecting and reinforcing public health functions

create the conditions for effective provision of services to vulnerable groups

create the conditions for effective provision of services to vulnerable groups

organise integrated and seamless care, linking preventive, acute and chronic care across all components of the health system

organise integrated and seamless care, linking preventive, acute and chronic care across all components of the health system

Primary Health Care as a set of activities

education concerning prevailing health problems and the methods of preventing and controlling them

education concerning prevailing health problems and the methods of preventing and controlling them

promotion of food supply and proper nutrition

promotion of food supply and proper nutrition

provision of an adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation

provision of an adequate supply of safe water and basic sanitation

provision of maternal and child health care, including family planning

provision of maternal and child health care, including family planning

immunisation against the major infectious diseases

immunisation against the major infectious diseases

prevention and control of locally endemic diseases

prevention and control of locally endemic diseases

appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries

appropriate treatment of common diseases and injuries

Primary Health Care as a level of care

The term ‘Primary Health Care’ is often used to refer to primary-level health services; that is, the first point of contact with the health system for people with health problems. In a Primary Health Care system, this level of care should be the most comprehensive. In this way, problems can be dealt with where they begin. Primary-level health services include community health centres, pharmacies and general medical practices. Non-government organisations and community groups can also be an important part of Primary Health Care services. However, these services can only be regarded as Primary Health Care services if the Primary Health Care philosophy underpins the way in which those first-level services are provided. That is, Primary Health Care practitioners’ work is guided by the principles of equity, social justice and empowerment. Community participation in decision-making, collaboration with health and other workers to deal effectively with health issues, and incorporation of health promotion and disease prevention is essential to their work.

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE, THE OTTAWA CHARTER FOR HEALTH PROMOTION AND THE NEW PUBLIC HEALTH MOVEMENT

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (see Appendix 2) was built on the progress made through the Declaration of Alma-Ata and defines health promotion as ‘the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health’ (WHO 1986). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion is regarded as the formal beginning of the New Public Health movement, a term that has widespread recognition, despite having been used several times before (Beaglehole & Bonita 2004: 214–17). The charter was the outcome of the first WHO International Conference on Health Promotion and was held in Ottawa, Canada, in 1986. The aim was to increase the relevance of the Primary Health Care approach to Minority countries that had largely ignored the Declaration of Alma-Ata. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986) highlighted the conditions and resources required for health and set out the action required to achieve Health for All by the Year 2000. Like the Declaration of Alma-Ata, the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion was, and is, a landmark document, laying out a clear statement of action that continues to have resonance for health workers around the world.

Putting health promotion into practice using the Ottawa Charter for Health promotion

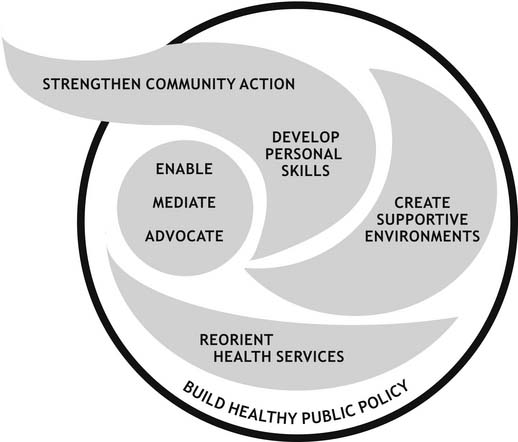

The strength of the Ottawa Charter lies in the fact that it incorporates both selective and comprehensive perspectives of Primary Health Care. Further, the five action areas of the Charter, used collectively within any population and within any setting, have a far better chance of promoting health than when they are used singularly (Kickbusch 1989). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion highlights the role of organisations, systems and communities, as well as individual behaviours and capacities. The five action areas of the Charter (see Figure 1.1) are designed to promote health by:

1. Building healthy public policy. It is not health policy alone that influences health: all public policy should be examined for its impact on health and, where policies have a negative impact on health, we must work to change them. For example, if a local government has a policy of allowing industrial complexes near residential areas, this would need to change if it was having a negative impact on residents’ health.

2. Creating environments which support healthy living. The protection of both the natural and built environment is important for health. In the built environment we need living, work and leisure environments organised in ways that do not create or contribute to poor health. For example, we need to provide affordable child care for working parents. We also need to conserve the natural environment for health. These will come through the establishment of healthy public policy.

3. Strengthening community action. Communities themselves are the experts in their own community and can determine what their needs are, and how they can best be met. Thus, greater power and control remain with the people themselves, rather than totally with the ‘experts’. Community development is one means by which this can be achieved.

4. Developing personal skills. If people are to feel more in control of their lives and have more power in decisions that affect them, they may need to develop more skills. This could include being provided with necessary information, training or other resources that would enable people to take action to promote or protect their health. Those who work in health must work towards enabling people to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to make informed decisions.

5. Reorienting health care. Health promotion is everybody’s business and intersectoral collaboration is the key. Within the health system there needs to be a balance between health promotion and curative services. One prerequisite for this reorientation is a major change in the way in which health workers are educated.

The New Public Health movement and the social model of health

The New Public Health movement builds on traditional public health approaches in three important ways. Firstly, the broad nature of health promotion is recognised, and the need to work with other sectors of government and private institutions whose work impacts on health. This intersectoral collaboration has become recognised as a central feature of effective health promotion. Secondly, the need to work in partnership with communities to increase community control over issues affecting health is recognised. Thirdly, the primacy of people’s environments (both physical and social) in determining their health, and the need to work for change to the environment rather than focusing on change solely at the level of the individual is recognised (Tones, Tilford & Robinson 1990, pp 3–4; WHO nd, available: http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/resources/intersectcoll/en/index.html).

Social and ecological perspectives

The philosophy and activities guiding the Environment movement and the Human Rights movement provide added weight to the philosophy of Primary Health Care. The United Nations (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Appendix 3) and The Earth Charter, 2000 (Appendix 4) resonate well with the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. In 1987, the year after the release of the Ottawa Charter, ‘Our Common Future’ (the Brundtland Report, UN 1987) called for ‘sustainable development’. This document, like the Declaration of Alma-Ata and the Ottawa Charter, is considered to be a seminal document. The principles that underpin sustainable development are:

inter- and intra-generational equity (social, economic and ecological)

inter- and intra-generational equity (social, economic and ecological)

practising the precautionary principle

practising the precautionary principle

Globally, there was a good deal of community and political action afoot at the time of the emergence of Primary Health Care philosophy, the New Public Health movement and the Environment movement. It is important to discuss both ecological and social justice perspectives and the relationship between the two. Ife and Tesoriero (2006) state that the perspectives of both need to be integrated to bring about a truly sustainable society. One of the reasons a social justice perspective is inadequate without an ecological perspective is because of the conventional economic prescription for many social problems brought about through economic growth. People working for ecological sustainability can challenge both the feasibility and desirability of continued growth, which Ife and Tesoriero (2006) see as contributing to the current ecological crisis. Both perspectives need to be understood in working toward enhancing health. Chapter 3 addresses these issue in more detail.

Affirming the philosophy: international health promotion conferences

The theme for the fourth conference, held in Jakarta (1997), was New Players for a New Era: Health Promotion into the 21st Century. It was the first time that the private sector had been included and there was some concern expressed at the conference about the difficulties of involving the private sector in health promotion policy development, with questions raised about the extent to which the private sector can be meaningfully involved without fundamental conflicts of interest (Hancock 1998). The conference declaration called for decision-makers in both the public and private sectors to demonstrate social responsibility by preventing harm to individuals and the environment, by restricting trade in harmful products and by integrating concern for equity into all policy development. In addition, conference delegates called for an increase in investment in health and areas that impact on health, including housing and education, demanding that particular attention be paid to groups who have poor health or are most vulnerable, including women, children, older people, and indigenous, poor and marginalised populations. The conference delegates stated that effective health and social development requires collaboration between all levels of government and society to make the changes necessary to improve health chances for all and that these partnerships must be ethical and based on mutual respect. Further, as health promotion is a participatory process, communities and individuals need to be provided with the necessary skills for, and access to, decision-making power to enable them to influence the determinants of health. Developing local-level expertise through education and dissemination of health promotion experience is necessary, as is ensuring that all countries have the necessary political, legal, educational, social and economic environments to support health promotion (WHO 1997). The conference delegates called for funding to establish and maintain infrastructures for health promotion locally, nationally and globally. They believed that efforts to motivate government and NGOs to mobilise resources for health promotion needed to be made (WHO 1997: 263).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree