Barbara Resnick, PhD, CRNP, FAAN, FAANP On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Define health promotion, health protection, and disease prevention. 2. Identify models of health promotion and wellness. 3. Describe health care provider barriers to health promotion activities. 4. Describe client barriers to health promotion activities. 5. Describe primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary prevention. 6. Plan strategies for nursing’s role in health promotion and public policy. 7. Develop approaches to support the empowerment of older adults. The purpose of health promotion and disease prevention is to reduce the potential years of life lost in premature mortality and ensure a higher quality of remaining life. As Americans live longer, health promotion activities are all the more important because these individuals will have more years to benefit from preventive services. Health promotion and disease prevention activities include primary prevention, or the prevention of disease before it occurs, and secondary prevention, which is the detection of disease at an early stage. Some evidence suggests that seniors benefit just as much from primary and secondary health promotion activities as those who are middle-aged. Exercise and reducing cholesterol levels improve overall health status and physical fitness, including aerobic power, strength, balance, and flexibility, and help prevent acute medical problems such as fractures, myocardial infarctions, and cerebrovascular accidents (Nelson et al, 2007; Thompson, 2005; Thompson et al, 2007; US Department of Health and Human Services: National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 2006). Appropriate screening with mammography, a Pap test, digital examination for monitoring prostate size, and/or yearly evaluation of stool specimens for occult blood may help reduce mortality and morbidity among older adults (Resnick & McLeskey, 2008). The incidence of ineffective health maintenance is high among older adults, as evidenced by the lack of participation in healthy behaviors such as exercise. Approximately, 22% to 47% of older women and 18% to 37% of older men do not engage in regular exercise (Crane & Wallace, 2007; Hsia et al, 2007; Rosamond et al, 2008). According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Diaz et al, 2007), 11.2% to 63.3% of adults met healthy diet parameters. Meanwhile, 20% to 60% of older adults do not adhere to prescribed medications (DiMatteo, 2004). There are many factors that put older adults at risk for having ineffective health maintenance (Table 8–1). Theoretically, reasons and decisions associated with engaging in health maintenance behaviors are best explained with the use of a social–ecologic model. This model incorporates intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, the environment, and policy. Intrapersonal factors include physical health, function, cognition, age, gender, and other relevant physiologic factors. Interpersonal factors include motivation and social supports. Environment includes both the physical environment, which might serve as a barrier or facilitator (being able to walk in a park for exercise or have access to an exercise room) of health behaviors, and the social environment. Lastly, policy can enforce and facilitate health behaviors through laws that require such things as bike helmets and seatbelts or that allow access through reimbursement. TABLE 8–1 FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE HEALTH BEHAVIORS IN OLDER ADULTS The interpersonal aspects of health behaviors are most often where nursing interventions can impact behavior. These are best guided by social cognitive theory. According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1997) human motivation and action are regulated by forethought. This cognitive control of behavior is based on two types of expectations: (1) self-efficacy expectations, which are individuals’ beliefs in their capabilities to perform a course of action to attain a desired outcome and (2) outcome expectancies, which are the beliefs that a certain consequence will be produced by personal action. The theory of self-efficacy suggests that the stronger the individual’s self-efficacy and outcome expectations, the more likely he or she will initiate and persist with a given activity. The factors that can influence self-efficacy and outcome expectations include successfully performing the behavior, verbal encouragement from others to perform the behavior, seeing similar persons perform the behavior, individualized caring and approaches to facilitate performance of the behavior, decreasing unpleasant sensations around the behavior (e.g., the pain associated with mammography; unpleasant drug side effects), and education about the benefit of the behavior (McAuley et al, 2006; Resnick, Luisi, & Vogel, 2008). Health promotion is the science and art of helping people change their lifestyle to move toward a state of optimum health. Optimum health is defined as a balance of physical, emotional, social, spiritual, and intellectual health (Green, 1996). The promotion of health provides the pathway or process to achieve this balance. Box 8–1 lists areas of health promotion most relevant to older adults. A distinction should be made between health promotion and disease prevention. Health promotion addresses individual responsibility, whereas preventive services can be fulfilled by health providers. Disease prevention focuses on protecting as many people as possible from the harmful consequences of a threat to health (e.g., through immunizations). Primary prevention is defined as measures provided to individuals to prevent the onset of a targeted condition (US Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2008). Specifically, primary prevention measures include activities that help prevent a given health care problem. Examples include passive and active immunization against disease, health-protecting education and counseling, promotion of the use of automobile passenger restraints, and fall prevention programs. Because successful primary prevention helps avoid the suffering, cost, and burden associated with injury or disease, it is typically considered the most cost-effective form of health care. Secondary prevention is defined as those activities that identify and treat asymptomatic persons who have already developed risk factors or preclinical disease but in whom the condition is not clinically apparent (USPSTF, 2008). These activities are focused on early case finding of asymptomatic disease that occurs commonly and has significant risk of a negative outcome without treatment. Screening tests for cancer are examples of secondary prevention activities. With early case finding the natural history of the disease, or how the course of an illness unfolds over time without treatment, can often be altered to maximize well-being and minimize suffering. Quaternary prevention involves limiting disability caused by chronic symptoms while encouraging efforts to maintain functional ability or reduce any loss of function through adaptation. For additional information regarding quaternary measures of prevention, see the specific disorders in Part 6 and Chapter 17. The second example is the Health Belief Model, developed to determine the likelihood of an individual’s participation in health promotion, health protection, and disease prevention services. Three basic components of this model are (1) the individual’s perception of his or her susceptibility to and the severity of an illness or disease, (2) modifying factors such as knowledge of the disease, various personal psychosocial and demographic variables, and cues or triggers to action, and (3) a cost–benefit ratio that is acceptable to the individual (Rosenstock, 1974). The PRECEDE/PROCEED Model (Green & Kreuter, 1999), the third example, is complex and incorporates community involvement in most aspects of its direction. It is firmly based on multidisciplinary scientific designs and studies from epidemiologic, educational, and psychosocial sciences. The PRECEDE phase, which stands for predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling constructs in education/environmental diagnosis and evaluation, examines life quality, health goals, and health problems. The PROCEED phase, which stands for policy, regulatory, and organizational constructs in educational and environmental development, examines implementation and evaluation. This model is particularly useful in planning health education programs. The fourth and final model is the Health Promotion Model. This model presumes an active role by the participant in developing and deciding the context in which health behaviors will be modified. Three basic categories are older adults’ characteristics and life experiences, their perceived personal decision making (self-efficacy), and the effect of the plan of action on health-promoting behaviors (Pender, 1996). There continues to be a lack of participation in health promotion activities among older adults. For example, the incidence of coronary vascular disease (CVD) is approximately 40% per 1000 person-years in older men and 22% in older women (Bourdel-Marchasson et al, 2005). The prevalence of inactivity, high fat and sodium diets, and poor adherence to medications among older adults is likewise high (Hekler et al, 2008; Hendrix, Riehle, & Egan, 2005; Kressin et al, 2007; Ostchega et al, 2007). Health professionals are often a contributing cause of lack of participation in health promotion among older adults. Although the guidelines are clear with regard to prevention of cardiovascular disease and the benefits of regular physical activity (American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association, 2008; American Heart Association, 2008; Kumanyika et al, 2008; Marcus et al, 2006; Mosca et al, 2007; Thompson et al, 2007), the guidelines around secondary prevention are not always as clear. The USPSTF (2008) evidence-based guidelines were created on the premise that screening will improve patient outcomes. However, screening for those 85 years or older seems contradictory because there are very little data that provide evidence that cancer screening tests are of any benefit for this age group. The USPSTF does address old age and gives upper age limits for the prostate-specific antigen test, mammography, Pap test, and most recently, colorectal cancer screening (USPSTF, 2008). A number of variables affect older adults’ willingness to engage in specific primary and secondary health-promoting activities. These include socioeconomic factors (Hendrix et al, 2005), beliefs and attitudes of both patients and providers (Dye & Wilcox, 2006; Fallon, Wilcox, & Laken, 2006), encouragement by a health care provider (Ory, Peck, Browning, & Forjuoh, 2007), specific motivation based on efficacy beliefs (Resnick et al, 2007), and access to resources. Age, number of chronic illnesses, mental and physical health, marital status, and cognitive status have all been associated with participation in health promotion activities (Hendrix et al, 2005; Resnick et al, 2007). Generally, individuals who are younger, married, have fewer health problems, and have better cognitive status are more likely to participate in primary and secondary health-promoting activities. These findings, however, are not consistent. Specifically Gallant and Dorn (2001) reported that the factors influencing health behaviors varied by behavior, gender, and race. Therefore it seems that there may be sample-specific differences with regard to what factors influence health promotion behaviors. Client barriers unrelated to health beliefs can include lack of transportation and financial limitations. Transportation is not readily available to many urban and rural older adults, or it is cost prohibitive (see Chapter 7). In addition, older adults incur the cost of many preventive services because Medicare does not cover them all (Table 8–2). This can be hard on the fixed, limited income of many older adults. TABLE 8–2 SECONDARY PREVENTION: MEDICARE REIMBURSEMENT Ethnic and cultural factors can have a negative effect on health care–seeking behaviors. The cultural diversity issue is complex and varies from one location to another throughout the United States (see Chapter 5). The diversity among communities has not been adequately considered by health policy makers. This creates barriers to programs; for example, some programs require older adults to forfeit personal and family privacy to obtain individual services. In some cultures a fear of reporting health screening results that could serve as the impetus for additional protective or preventive services limits program development. Another problem in culturally diverse areas is a lack of coordination of preventive health services because of the differing ideas and beliefs held by health policy makers concerning the delivery of services. Older adults vary with regard to their willingness to engage in health-promoting activities. With age, they may have less interest in engaging in health promotion activities for the purpose of lengthening life and a greater interest in engaging in these activities only if they improve their current quality of life. It is useful, therefore, to use an individualized approach to health promotion with older adults(Resnick & McLeskey, 2008). Health protection is a classification of the Healthy People 2020, which is in development by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Healthy People 2020, a revision of Healthy People 2010, will provide our country with guidelines for how to achieve a wide range of public health benefits. Primary prevention refers to some specific action taken to optimize the health of the older individual by helping him or her be more resistant to disease or to ensure that the environment will be less harmful. Overall guidelines for reimbursable primary prevention are reviewed in Tables 8–2 and 8–3. Many of these behaviors require ongoing behavior changes and thus should be incorporated into all interactions with older individuals. TABLE 8–3 Generally, immunizations are strongly recommended for older adults and include an annual influenza vaccination in the early autumn of each year and a regular tetanus vaccination every 10 years. All older adults should receive a pneumococcal vaccination at or immediately after the 65th birthday, and an additional vaccination after 5 years or more is recommended for high-risk persons. Adults with high-risk status include those living in institutions and those with chronic medical conditions such as heart or lung disease, diabetes mellitus, or cancer. It should be noted, however, that the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) does not recommend routine revaccination of immunocompetent older adults; persons ages 65 or older should only be administered a second vaccination if they received the vaccine more than 5 years previously and were younger than age 65 at the time of primary vaccination (CDC, 2008). Another risk factor for older adults is polypharmacy (see Chapter 22). Polypharmacy is the use of large quantities of different drugs to relieve symptoms of health deviation or symptoms resulting from drug therapy (Holmes et al, 2006). Polypharmacy is compounded by the use of generic drugs or the substitution of over-the-counter drugs that are less potent than their prescription counterparts. There is increased focus on medications during care transitions, and nurses need to continue to completely review all medications taken routinely, randomly, by prescription, from friends, and over-the-counter during all medication reviews. The list of medications should be reviewed for interactions, contraindications, and overmedication or overdosing. Prevention should also focus on bone health through optimization of calcium and vitamin D intake and exercise (Office of the Surgeon General, 2004), oral health through daily oral care and monitoring (American Dental Health Association, 2009), and prevention of cardiovascular disease through exercise (American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association, 2008), heart healthy diets (American Heart Association, 2008), and adherence to appropriate medications. The USPSTF also provides guidelines regarding screening for cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, diabetes, and obesity (USPSTF, 2008). There is some evidence to support screening for osteoporosis. hyperlipidemia, depression, and obesity. There is insufficient evidence to support screening for triglycerides or dementia. Decisions about screening should only be made after carefully weighing the benefits against the possible risks; knowledge about how the information will be used should also be obtained (Table 8–4). For example, screening for breast cancer knowing that the older individual would refuse any further treatment should probably not be done. TABLE 8–4 Protective effect on heart disease Increases high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol Decreased mortality after heart attack

Health Promotion and Illness/Disability Prevention

Essentials of Health Promotion for Aging Adults

FACTOR

DESCRIPTION

Cognitive impairment

Can result in a lack of understanding of the health behavior and rationale for engaging in the behavior (e.g., doesn’t understand the impact of not taking medications, not exercising) and/or can result in the individual simply not remembering to engage in the activity.

Function

Inability to physically engage in the health maintenance recommendations (e.g., cannot tolerate preparation for a colonscopy, can’t complete stool cards, cannot see to read medication directions).

Access to care

Inability to get to grocery stores with appropriate food options, inability to access health care providers due to transportation challenges, insufficient numbers of providers, etc.

Resources

Cannot afford health food options, medications, etc.

Social supports

Social supports can verbally encourage and reinforce healthy behaviors and can help individuals increase access to healthy options.

Sensory changes

Inability to see or hear adequately to engage in a behavior (e.g., cannot hear or see the directions)

Environment

Living space that facilitates physical activity and exercise or does not allow for physical activity.

Unpleasant sensations

Pain, fear, boredom, and fatigue are common uncomfortable sensations that decrease willingness to engage in a behavior such as exercise or getting a screening test done.

Competing priorities

Lack of time due to competing responsibilities is frequently used as an excuse for not engaging in healthy behavior.

Terminology

Models of Health Promotion

Barriers to Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Health Care Professionals’ Barriers to Health Promotion

Older Adults’ Barriers to Health Promotion

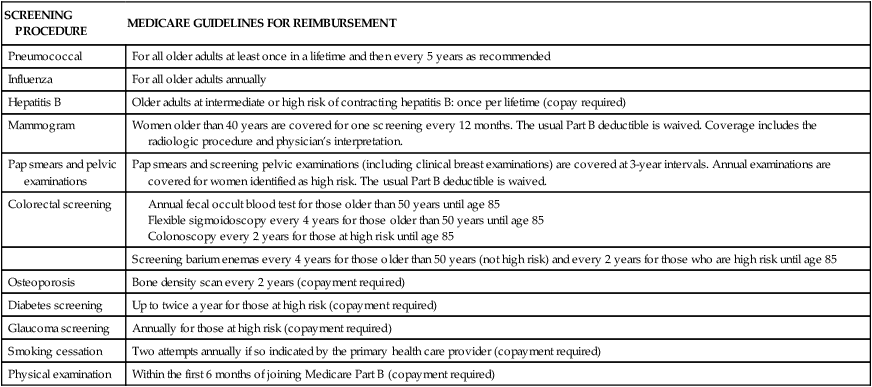

SCREENING PROCEDURE

MEDICARE GUIDELINES FOR REIMBURSEMENT

Pneumococcal

For all older adults at least once in a lifetime and then every 5 years as recommended

Influenza

For all older adults annually

Hepatitis B

Older adults at intermediate or high risk of contracting hepatitis B: once per lifetime (copay required)

Mammogram

Women older than 40 years are covered for one screening every 12 months. The usual Part B deductible is waived. Coverage includes the radiologic procedure and physician’s interpretation.

Pap smears and pelvic examinations

Pap smears and screening pelvic examinations (including clinical breast examinations) are covered at 3-year intervals. Annual examinations are covered for women identified as high risk. The usual Part B deductible is waived.

Colorectal screening

Screening barium enemas every 4 years for those older than 50 years (not high risk) and every 2 years for those who are high risk until age 85

Osteoporosis

Bone density scan every 2 years (copayment required)

Diabetes screening

Up to twice a year for those at high risk (copayment required)

Glaucoma screening

Annually for those at high risk (copayment required)

Smoking cessation

Two attempts annually if so indicated by the primary health care provider (copayment required)

Physical examination

Within the first 6 months of joining Medicare Part B (copayment required)

Health Protection

Disease Prevention

Primary Preventive Measures

HEALTH PROMOTION ACTIVITY

RECOMMENDATION

SUPPORTIVE EVIDENCE

Mammogram

Annually starting at age 40 and continue every 1–3 years until ages 70–85

Based on randomized trials; evidence for age to stop screening not well established

Pelvic examination/cervical smear

Every 1–3 years after 2–3 negative annual examinations; can discontinue after age 65 if prior testing was normal and not high risk

Based on randomized trials and evidence that harm outweighs the benefits

Fecal occult blood test

Annually after the age of 50 until age 85

Evidence from nonrandomized or retrospective studies; fair evidence to support recommendation

Prostate examination

Evidence is insufficient to support screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. Men older than 75 years of age should not be offered a PSA test routinely.

Based on insufficient evidence to support the benefits of screening

Exercise

Encourage aerobic and resistance exercise as tolerated; ideally 30 minutes of moderate exercise daily

Based on randomized trials

Low-cholesterol diet

Keep daily fat intake at less than 35% of total calories and saturated fat and trans fatty acid intake at less than 7% of calories

Guidelines established, although not clear about guidelines for those age 85 years or older

Routine aspirin use

Low-dose aspirin therapy should be discussed with patients and benefits/risks evaluated.

Based on randomized controlled trials

Alcohol intake

Moderate alcohol use, defined as 1 drink daily that does not exceed 1.5 ounces (45 mL) of liquor, 5 ounces (180 mL) of wine, or a standard can of beer (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2001)

Guidelines/safety not well established

Secondary Preventive Measures

ACTIVITY

ADVANTAGES

DISADVANTAGES

Alcohol use

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Health Promotion and Illness/Disability Prevention

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access