Chapter 13 Health promotion

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

define health education and health promotion, and understand their histories and place in public health

define health education and health promotion, and understand their histories and place in public health discuss health promotion actions and strategies, and their applications for practice in various settings and populations

discuss health promotion actions and strategies, and their applications for practice in various settings and populationsIntroduction

The ‘promotion of health’ has become everybody’s business, including the marketers of ‘healthy’ products/lifestyles and gym memberships; government media campaigns such as ‘Go for 2&5©’ (fruit and vegetables); special ‘extra’ benefits for joining a private health insurance fund; and workplace ‘wellness’ programmes. For consumers, the list is endless. Health professionals need to understand the background to this growth in promoting ‘health’ and the place health promotion plays in public health. We begin this chapter with a discussion of health education; we then trace the evolution of health promotion from health education, to the strategies and settings for health promotion, and conclude with challenges for health promotion. Case studies, activities and reflections on the material are presented.

History of health education

Health education has had a long history in public health. Education concerning prevailing health problems and the methods of preventing and controlling them is the first of the eight basic elements of primary health care (WHO 1978). Health education is about educating individuals about specific illnesses and disease, so that they can make informed decisions about preventing the onset of these conditions, or maintaining and restoring health, usually by changing their behaviour.

Ritchie (1991) described four phases of health education activity and experience in Australia. The first stage was education through the provision of health information. Health professionals were ‘perceived as being invested with all pertinent knowledge, and health practitioners were seen as the prime source responsible for the health of individuals’ (Ritchie 1991 p 157). Although great efforts were made by health professionals in providing information to patients/clients, information alone was not producing the desired effects. In Stage 2 (the early 1970s), health information and education programmes were delivered through audio-visual channels, such as films, leaflets, posters and teaching kits. Ritchie (1991) claimed that even with all these additions, health professionals were still ‘talking heads’ and some of the printed brochures were in obscure scientific language. In Stage 3, health educators used adult education principles. First espoused by Malcolm Knowles (1913–1998), adult education principles include empathy, experiential learning, participation and authenticity. He coined the term ‘androgogy’ (the study of adult learning) and education was through ‘guided interaction’ (Boshier 1998). Adults learned by building on their own experiences, particularly in groups with other adults. For health professionals, group work that used these principles was energetically pursued, with the assumption that behaviour change to improve health was a voluntary choice. The premise was that receiving the correct information would automatically lead to behaviour change. When people did not change, despite the best efforts of health professionals, patients/clients tended to be ‘blamed’. This led to the term ‘victim-blaming’ (Ritchie 1991 p 160). Stage 4 in health education development in Australia was the combination of improving individuals’ knowledge, skills and understanding, but within the context of their social and environmental milieu.

Mass health education campaigns broadened from a focus on educating individuals about their health, to health education campaigns aimed at changing the behaviour of populations in the 1970s and 1980s. The two earliest of these large community-wide programmes were the Stanford Three-Community Study in California, and the North Karelia Project in Finland. The study in North Karelia (population of 180 000) showed that Finnish men had the world’s highest mortality rate from ischaemic heart disease in 1972. A health education programme was started to see whether the main risk factors of high blood pressure, high cholesterol and smoking could be reduced in the population and whether this would reduce mortality from cardiovascular diseases (Vartianen et al. 2000).

The Stanford Three-Community Study in California (1972–1975) ‘targeted cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors through a health promotion programme using mass media supplemented by individual and group education for high-risk persons in one town and mass media alone in a second town; a third town served as a control’ (Fortmann & Varady 2000 p 316). This programme promoted a reduction in cholesterol levels through dietary changes, a reduction in blood pressure with regular blood pressure monitoring, an increase in physical activity and a reduction in cigarette smoking, salt intake and obesity. The campaigns had limited effects in these trial communities (Fortmann & Varady 2000). Health education still has a significant role to play in providing health information for patients and communities. This knowledge is about how to raise awareness of health issues in the community, assist patients in exploring their attitudes and values about health problems and educate policy makers about important health issues. Knowledge of effective health education strategies, particularly the application of theories of individual behaviour change, is essential for health professionals who work with individuals. This understanding takes on a special significance as the health profile of the population changes, with the consequent rise in chronic diseases. See Chapter 3 to refresh your knowledge. Health education definitely has a place for nurses and allied health professionals in the individual counselling of patients about self-management; environmental health officers educate restaurant staff regarding safe food handling practices; and physicians educate their patients about vaccinations. Patients have the right to know about their care, but as a whole-of-population approach, health education alone is limited.

The concept of wellness

Wellness is a term that has evolved through health interests in the United States. Unsatisfied with the term ‘health’ and its origins in the ‘absence of disease’, some American health professionals claimed this definition of ‘health’ was limited. Health education should be about improving ‘wellness’; that is, people’s sense of wellbeing. Wellness programmes have sprung up in organisations as employee wellness programmes. They focus not only on keeping employees physically active and healthy, but also on the spiritual, emotional and social aspects of health. Navarro et al. (2007), in an article about new strategic directions for public health, assert that there is a need to examine new approaches for health and wellness. They note that ‘fragmentation and overemphasis on the physical aspects of health exclude mental health, spirituality and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as integral parts of wellness’ (Navarro et al. 2007 p 4), and call for research funding to investigate further these influences on community health outcomes.

Evolution and evidence for health promotion

After the World Health Organization (WHO) Declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978 (WHO 1978), and its Health for All strategy, the concept of health promotion emerged. Catford (2004) argued that ‘health promotion’ was becoming increasingly used by a new wave of public health activists who were dissatisfied with the traditional and top-down approaches of ‘health education’ and ‘disease prevention’. Health promotion, as a public health strategy, was a more radical approach, because it assumed that people’s health was determined not only by their own behaviour but by the contexts in which they lived and worked. We discussed contexts and the importance of socio-economic influences on health in Chapter 6, and how health opportunities were mediated through people’s social, emotional and physical environments. To improve health within a population, a ‘new public health’ was needed to tackle these socio-environmental determinants of health, as research revealed that multiple strategies across many sectors – government, non-government and industry – were needed to create and provide health opportunities for all. The analysis of promoting and improving population health became more sophisticated.

Catford (2004) claimed that there have been three stages in the development of health promotion since the 1970s. The first was ‘tackling preventable diseases and risk behaviours’ (e.g. heart disease, cancer, tobacco and nutrition), through education (Catford 2004 p 3), commonly termed ‘health education’. The Stanford and North Karelia programmes could be included here. The second stage of health promotion was the ‘complementary intervention approaches’ (Catford 2004 p 3), with a range of action areas, such as the development of healthy public policy, personal skills, supportive environments, community action and health services. The third was ‘the value of reaching people through the settings and sectors in which they live and meet (e.g. schools, cities, health care settings, workplaces)’ (Catford 2004 p 3). This became known as the ‘settings’ approach for health promotion. Although not specifically identified by Catford (2004), there is a fourth dimension for the 2000s that needs to be examined, that is, the social determinants of health in an increasingly globalised world. Some of these issues include: the migration and movement of people in Europe, since the establishment of the European Union; and the pressure on the world’s cities as increasing numbers of people move from agrarian-based economies to market-based economies – for example, the mass migration to cities in South-East Asia to work in clothing and textiles, and technology-based industries. There are increasing disparities in the standard of living between developed countries and developing countries; changing weather patterns that impact on water supplies, and hence agriculture; and war and the consequent displacement of millions of people to refugee camps. All these factors create challenges for public health. Therefore, health promoters need the skills to analyse the impact of such social determinants on health and to advocate for public health policies that create health opportunities for all.

Regarding the evidence for health promotion and the need to devote resources to the prevention agenda to improve the health of the population, Catford (2009 p 1) asserts that ‘the tide has turned with mounting evidence of the value and cost-benefit of health promotion’. The UK Treasury looked at the economic value of health promotion and the rising costs of health care and concluded that there needed to be ‘more investment in public health and health promotion …’ (Wanless 2002 p 1). There is increasing evidence of the cost-benefit and value of health promotion where small investments in disease prevention programmes are warranted (Trust for America’s Health 2008). For example, ‘an investment of $10 per person per year in proven community-based programmes to increase physical activity, improve nutrition and prevent smoking and other tobacco use could save the country (US) more than $16 billion annually within 5 years’ (Trust for America’s Health 2008 p 1).

In Australia, Vos et al. (2010) produced a 3-year comprehensive report (ACE Prevention Report) on the cost-benefit of prevention programmes, with the guidance of 130 experts. Over 150 preventive health interventions were evaluated in terms of their cost effectiveness and their genuine impact on the health of Australians. Some of the proven prevention interventions included a 30% increase in tax on tobacco. The federal government’s increase on tobacco tax was 25% in the May 2010 budget, and a 10% increase in the tax on alcohol was also implemented. The tax on alcohol will eventually be based on an equalised volumetric taxation system per litre of alcohol. Currently there are different taxes on different types of alcohol (beer, spirits, wine).

Activity

Discuss the following questions with other students and write down your answers.

Principles of health promotion

In 1986, the WHO declared a set of principles that underpinned health promotion. ‘ “Health” was the extent to which individuals and groups are able to realise their aspirations and satisfy needs and to change or cope with the environment’ (Health Promotion International 1986 p 73). The principles underpinning health promotion are:

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO 1986) articulated a way forward for the new public health. While not explicit, it posed the question, ‘What really creates health?’ (Kickbusch 2007). The charter used the WHO (1984) health promotion principles as a foundation for five action areas. It outlined a decisive platform for health promotion action. Significantly, there were specific prerequisites for health. These were ‘peace, shelter, education, food, income, a stable ecosystem, sustainable resources, social justice and equity’ (WHO 1986 p 1). These prerequisites are still the cornerstone for health actions. Health was seen as a ‘resource for everyday life, not the object of living’ (WHO 1986 p 1). This represents a positive concept of health instead of explaining ‘health’ as merely the absence of disease. The definition of health promotion was to ‘enable people to take control over their health’. The concept of empowerment was implicit in health promotion and described as ‘a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health’ (WHO 1998). ‘Health promotion not only encompasses actions directed at strengthening the basic life skills and capacities of individuals, but also at influencing underlying social and economic conditions and physical environments which impact upon health’ (WHO 1998). The role of health professionals in health promotion is to practice ‘with’ people not ‘on’ them.

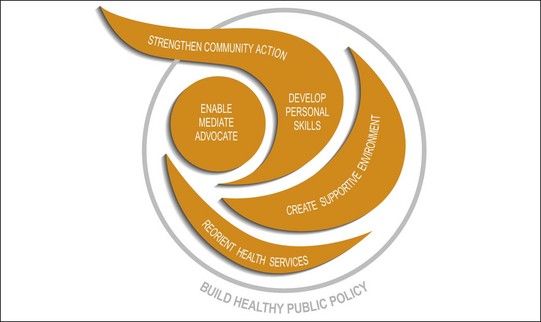

The Ottawa Charter (1986) became a ‘focal point in the work of the World Health Organization (WHO) in advocating a comprehensive approach to public health and health promotion practice’ (Fleming & Parker 2007 p 6). It was based on the social democratic principles of justice, equity and access. This translates to a public health practice that addresses the determinants of ill health in societies. For more detail, see the Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) website. There are five essential actions, outlined in Figure 13.1.

Here are some examples of the application of these action areas to contemporary health problems:

Since 1986, WHO assemblies focusing on health promotion have been held regularly; each of these assemblies explores specific aspects of health promotion to strengthen the discipline. For example, in 1988 in Adelaide, healthy public policy was the focus (WHO 1988); in 1991, in Sundsvall, Sweden, attention was focused on ‘creating supportive environments for health’ (WHO 1991); in Jakarta, 1997, the dominant themes were partnerships and settings (WHO 1997a). In 2000, the Fifth International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Mexico City in 2000 (WHO 2000); its theme was bridging the equity gap with a focus on the determinants of health. The Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in a Globalised World stressed the ‘progress towards a healthier world requires strong political action, broad participation and sustained advocacy’ (WHO 2005). In Nairobi in 2009, the 7th Global Conference on Health Promotion focused on closing the implementation gap in health and development through health promotion (WHO 2009). These conferences and actions are frameworks for propelling continued action for advancing health. They continue to embed the principles of health promotion as a sustaining and integral part of public health.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s concepts of health promotion

In Chapter 1, you were introduced to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s definition of health. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, ‘health’ is interlinked with families, communities and land. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health promotion needs to consider the individual, family and community. Health professionals need to understand the dynamics of the cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and be culturally competent. Health promotion uses a primary health care and a ‘strength-based’ approach to improve health in communities. A primary health care approach integrates ‘both an individual and the population’ as its hallmark (Couzos & Murray 2003 p xxxi). ‘Primary health care’, according to the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), is designed as ‘essential, integrated care based upon scientifically sound and socially acceptable procedures and technology made accessible to communities (as close as possible to where they live) through their full participation, in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination’ (Couzos & Murray 2003 p xxxii). Through the more than 130 Aboriginal community-controlled health services (ACCHSs) that are managed by boards of elected Aboriginal members, integrated care for the community is offered through individual treatment and promotion programmes, as well as extensive community health screening and health promotion programmes. The Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations exemplify how health services mix successfully the incorporation of medical services and health promotion, and thus enact the ‘reorienting health services’ action step from the Ottawa Charter.

Brough et al. (2004) argues that health promotion in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities needs to focus on the cultural assets within the communities. In other words, the starting point for health promotion should be the ‘strengths’ that exist within communities rather than a more traditional approach to health promotion that focuses on ‘deficits’ such as people’s unhealthy behaviours. The authors asked over 100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in urban Brisbane to identify the strengths in their community; ‘… many were surprised … as most were used to being asked about problems, not strengths’ (Brough et al. 2004 p 217). Five key strengths were named: (1) extended family, (2) commitment to community, (3) neighbourhood networks, (4) community organisations, (5) community events. These community ‘assets’ laid the foundation upon which to strengthen existing community initiatives such as adding professional training to a community football team and ‘the provision of a youth nutrition programme in an Indigenous youth organisation’ (Brough et al. 2004 p 219). This approach to health promotion clearly links with the Ottawa Charter’s Action Step, ‘strengthen community action’.

For a full account of the development and structure of these Aboriginal medical services, and for a wide-ranging profile of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s health, policies and services, see Chapter 15, and the NACCHO website.

Activity

One of the principles of health promotion is that the strategies need to be intersectoral and engage participants, as the focus of health promotion is to ‘enable all people to achieve their fullest potential’ (WHO 1986). The WHO articulated a broad range of approaches to health promotion, summarised below.

Nutbeam (2005) provides some commentary on how the Ottawa Charter (1986) would appear if written now. ‘Health promotion will certainly involve partnerships with the private sector in ways that were inconceivable in 1986’ (Nutbeam 2005 p 2). A range of businesses and organisations promote fundraising for breast cancer research through selling pink ribbons. Several years ago, such a promotion would have received scant attention in the media, and would certainly not have the profile through the private sector that it has now.

If we use ‘supportive environments for health’ to focus on the physical environment, much has changed since the Ottawa Charter in 1986. Climate change and environmental damage have primarily been the domain of environmentalists. Now, health professionals and environmentalists collaborate because degradation of rainforests increases mosquito-borne disease and climate change alters ocean flows, with the consequential depletion of fish stocks and, therefore, food resources (See Chapter 11 for more on environmental health).

An analysis of eight reviews of the Ottawa Charter’s (1986) health action areas, published between 1999 and 2004, assessed the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of health promotion interventions (Jackson et al. 2006). Significant lessons are:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree