On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Describe acute care hospital use patterns in the older adult population. 2. Describe a functional model of nursing care. 3. Identify risks associated with hospitalization of older adults. 4. Identify ways to modify the physical and social environment to improve care for hospitalized older adults. 5. Identify special considerations in caring for critically ill older adults and older adults suffering from trauma. 6. Describe two nursing interventions for each of the three conditions that make up the geriatric triad. 7. List adaptations that can be made to facilitate learning in older adults. 8. Describe a profile of a “typical” noninstitutionalized older adult, including common diagnoses and functional limitations. 9. Distinguish the categories and types of home care organizations in existence. 10. Explain the benefits of home care. 11. Analyze the effect of the recent changes instituted by Medicare on home health agencies and home health clients. 12. Discuss the philosophy of hospice care and how it differs from traditional home health care. 13. List five common factors associated with institutionalization. 14. Identify differences between the medical and psychosocial models of care for institutional long-term care. 15. Summarize key aspects of resident rights as they relate to the nursing facility. 16. List assessment components included in the minimum data set of the Resident Assessment Instrument. 17. Describe common clinical management programs in the nursing facility for skin problems, incontinence, nutritional problems, infection control, and mental health. 18. Differentiate types of nursing care delivery systems found in the nursing facility. 19. Describe assisted living, special care units, and subacute care units as specialty care settings of the nursing facility. The older-than-85 group is the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population. The most common diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) in hospitalized older adults (older than 85) include heart failure, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, cerebrovascular disorders, digestive disorders, gastrointestinal hemorrhages, nutritional and metabolic disorders, rehabilitation, and renal failure (National Center for Health Statistics, 2006). The major causes of death in those older than 65 are heart disease, cancer, stroke, chronic lower respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus, accidents, pneumonia, and influenza (National Center for Health Statistics, 2006). Polypharmacy (taking five or more drugs during the same period) is a common cause of iatrogenic illness (Kane, Ouslander, & Abrass, 2004) Hospitalized patients are often admitted with a large number of prescribed, over-the-counter, and homeopathic drugs in their bodies; when given additional medications during their hospital stay, they have a heightened risk for an adverse drug reaction. Conversely, adverse drug reactions frequently precipitate hospitalizations and, although often unreported, are among the most common iatrogenic events in the acute care setting. The hospital staff needs to get an accurate drug history of a patient, be aware of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes related to aging, and have a working understanding of drug–disease, drug–drug, and drug–food interactions in older adults (Hilmer & Gnjidic, 2008). Nurses should be particularly aware of drugs that may be high risk when used in older adults and carefully monitor patients taking them for signs and symptoms of toxicity (Hilmer & Gnjidic, 2008). Studies indicate that up to 79% of all adverse inpatient incidents are related to falls, and patients age 65 or older experience the most falls; approximately 10% fall more than once during their hospital stay, usually in their hospital room (Krauss et al, 2007). Risk factors for hospital falls include both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include age-related physiologic changes and diseases, as well as medications that affect cognition and balance. Extrinsic factors include environmental hazards such as cluttered hospital rooms, wheels on beds and chairs, and beds higher than what an older adult usually has at home. The hospital is sometimes a dangerous and foreign place for inpatients because of unfamiliarity and because of changes in the patient’s medical condition (Tzeng & Yin, 2008). The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) (2009) emphasized the need to improve patient fall risk by improving the environments of patient rooms, staff abilities, and interventions (see Chapter 12). Older adults are generally more vulnerable to infections because of physiologic changes in the immune system and underlying chronic disease (see Chapter 17). The health care–associated infection rate for hospitalized patients in general is approximately 5%, and 65% of this occurs in the older patient (older-than-60) population (Merck Manual of Geriatrics, 2005). This may be a low estimate because the atypical presentation of older adults with infections makes infections more difficult to diagnose. The respiratory and urinary tracts are the most common sites of infection. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) occur frequently, although bacteriuria in an older adult is often asymptomatic. Subclinical infection and inflammation can occur with presenting symptoms such as acute confusion, functional capacity deterioration, anorexia, or nausea rather than the classic symptoms of fever and dysuria. Increased instrumentation and manipulation and decreased host immune mechanisms contribute to the increased risk of elderly patients developing sepsis originating from the urinary tract (Cove-Smith & Almond, 2007). Other common sites of infection in hospitalized older adults include the skin, soft tissues, wounds, the gastrointestinal tract, and blood. Older adults are at increased risk for colonization and infection with antibiotic-resistant strains of organisms (Merck Manual of Geriatrics, 2005) such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Control of the spread of resistant strains of organisms continues to be a problem in institutional settings. Adhering to basic principles of infection control is critical for nurses. It is essential to comply with proper hand washing, disinfection of the environment, and appropriate precautions when caring for patients infected or colonized with resistant strains. Once older adults are hospitalized, immobilization through enforced bed rest or restraint often results in functional disability. Immobilized patients are vulnerable to rapid loss of muscle strength, reductions in orthostatic competence, urinary incontinence or retention, fecal impaction, atelectasis and pneumonia, acute confusion, depression, skin breakdown, and many other complications (Kane et al, 2004). The occurrence of iatrogenic illnesses often represents a vicious circle, referred to as the cascade effect, in which one problem increases the person’s vulnerability to another one. Gerontologic nurses must be leaders in advocating more appropriate care and treatment of hospitalized older adults to prevent or at least reduce the occurrence of iatrogenic illness. Developing nursing competency helps the nursing staff customize the care provided to patients age 65 or older. It enhances the nurse’s job performance and the quality of care delivered. The JCAHO (2009) requires documentation that all staff members (e.g., nurses, unlicensed assistive personnel, phlebotomists, and physical therapists) have a documented competency assessment that includes the special needs and behaviors of the specific patient age groups (e.g., geriatric, pediatric, and adolescent) that are being cared for in the assigned area. JCAHO further requires that this be done on initial employment and then periodically reviewed. A priority at the beginning of every hospitalization is the assessment of the older adult’s baseline functional status so that an individual care plan can be developed within the acute care environment (Kresevic, 2008) (Box 9–2). Systematic functional assessment in the acute care setting also provides a benchmark of a patient’s progress as he or she moves along the continuum of care, and it promotes systematic communication of the patient’s health status between health care settings (Kresevic, 2008). Assessment in the acute care setting includes recognition that older adults are in an unfamiliar environment, which is not conducive to optimal functioning at a time when reserves and homeostatic needs are compromised by acute illness. Many common assessment tools for ADLs and mental status assess areas of function that may not be easily evaluated at the time of admission or may not be significant at that time (i.e., orientation when a calendar is not present in the room and when daily routines are disrupted). The primary goal of the acute care nurse is to maximize the older patient’s independence by enhancing function. Functional strengths and weaknesses need to be identified. The care plan must provide for interventions that build on identified strengths and help the patient overcome identified weaknesses (see Chapter 4). Function integrates all aspects of the patient’s condition; any change in functional status in an older adult should be interpreted as a classic sign of illness or as a complication of their illness. By knowing an older patient’s baseline function, the nurse can assess new onset signs or symptoms before they trigger a downward spiral of dependency and permanent impairment. Nursing expertise is particularly needed in the acute care setting to guide the nursing staff in understanding the unique needs of older patients and enhancing their skill in managing common geriatric syndromes (Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, 2008). The advanced practice nurse functions in the role of clinician, educator, consultant, and researcher. A growing number of acute care settings are recruiting and hiring advanced practice nurses. Nurse practitioners are also being employed to assist with the day-to-day assessment and management of patients in the acute care setting. Some studies demonstrate a significant decrease in the length of stay when patients are comanaged by a nurse practitioner and an attending physician (Markle, 2004). The advanced practice nurse can be instrumental in developing and implementing protocols for managing common geriatric syndromes like those defined in the geriatric triad. The geriatric triad includes falls, changes in cognitive status, and incontinence (Farooqi, 2007). These three conditions need special attention during hospitalization. Falls can be a classic sign of illness for older adults; an older adult in the acute care setting is often at high risk for falls and consequent injuries. A strange environment, confusion, medications, immobility, urinary urgency, and age-related sensory changes all contribute to this increased risk. Falls resulting in injury can be minimized by gait training and strengthening exercises, appropriate nutrition, careful monitoring of medications, supervised toileting, environmental modifications, proper footwear, and control of orthostatic hypotension (Overcash & Beckstead, 2008). Bed and leg alarms to provide warnings of patient movement, thereby minimizing falls, are being tested in many institutions (see Chapter 12) (see Emergency Treatment Box). Older adults admitted to the hospital are often critically ill, and effective nursing care requires an understanding of their impaired homeostatic mechanisms, their body systems’ diminished reserve capacity, and their impaired immune response. The homeostatic mechanisms are altered with age so that the abilities to generate a fever, to respond to alterations in tissue integrity, and to sense pain may be very different from those manifested by young or middle-age adults in critical care (Merck Manual of Geriatrics, 2005). The atypical and subtle nature of disease presentation becomes even more important in the intensive care unit (ICU), where the patient is often less able to articulate discomfort and new problems can arise quickly. The nurse must be aware that the most common presenting symptom of sepsis in older patients is acute mental status change (Martin, Mannino, & Moss, 2006). Astute observation for delirium is essential in aggressively managing its underlying cause (see Chapter 29). Delirium in this setting in the past was referred to as “ICU psychosis” and was thought to be due to sensory overload or sensory deprivation. The causes are now recognized as multifactorial and, in this environment, are often secondary to acute illness, drugs, and the environment. Critically ill individuals are at particular risk for delirium because of impaired physical and mental defenses (Alagiakrishnan & Blanchette, 2007) (Table 9–1). TABLE 9–1 Two additional issues for critical care of older adults are prevention of nutritional compromise and recognition of adverse drug reactions. Up to 65% of hospitalized older adults are malnourished on admission or acquire nutritional deficits while hospitalized (Ranel, Jonsson, Bjornsson, & Thorsdottir, 2007). In the critical care setting, patients are sicker and have ever-changing metabolic requirements that necessitate daily nutritional monitoring. Clinical recognition of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes associated with aging is most important in the critical care setting, where more drugs are used to combat more problems (see Chapter 22). Drugs given in the critical care context can be lifesaving and life threatening at the same time (Rellos, Falagas, Vardakas, & Sermaides, 2006). The most common traumatic injuries (see Chapter 12) experienced by those older than age 65 are a result of falls, automobile accidents, and burns. Older adults suffer injuries of equivalent severity to those of younger persons; however, the consequences are more severe (Takanishi, Yu, & Morita, 2008). It is essential to obtain a thorough history of an injury from the patient and his or her family, including the circumstances surrounding the event and the events leading up to the injury. Health care professionals in the field need to realize that older adults do not tolerate hypoperfusion long and can quickly go into cardiogenic shock and multisystem organ failure. Early hemodynamic monitoring is required. The vital signs of an older adult might be restored to normal, yet the person might still be in cardiogenic shock (Filbin, 2008). As much as volume depletion is a concern, so is volume overload in patients with limited cardiac and renal reserves. Insertion of a catheter does increase the risk of infection in older adults but is often justified for its monitoring value (Filbin, 2008). Thermoregulatory mechanisms become impaired as a person ages, and older adults with trauma are particularly vulnerable. Care should be taken to reduce heat loss with the use of warm intravenous solutions, warm blankets, and proper environmental control. The degree of long-term recovery of older adults who survive injury is variable, and aggressive rehabilitation and social support are important factors in recovery. Research supports the fact that older adults are at greater risk for complications and higher mortality even when injuries are not severe (Filbin, 2008). Supporting and facilitating self-care behaviors for older patients and their families are responsibilities of the health care team, but such activities are most often implemented and coordinated by the nurse. Adaptations can be made to support and facilitate learning in older adults via the sensory, motor, and cognitive systems (Box 9–3). Assessment of sensory and cognitive status is the first step in determining whether adaptations are needed. Sensory and cognitive changes require a multisensory approach. Teaching strategies should be individualized and need to include multiple sensory stimuli: seeing, hearing, touching, and smelling. Also important may be the presence of family members or other home caregivers during the teaching process to prepare them to reinforce information needs once a patient is home (Box 9–4). Motivation and rewards to enhance learning and compliance with needed self-care are specific to each individual. Compliance with new health care regimens can be promoted by clearly identifying benefits of behaviors that are of value to the patient, reinforcing information through support systems, and involving significant others in the learning process. Older adults are much more capable of using previous experiences to problem solve than are younger persons. The nurse should teach what is immediately applicable to the life of an older adult. Decreasing the risk of a heart attack may not be nearly as important as increasing function so that the older adult can go to church or spend time with family. The content of teaching should address not only the care of a given disease but also the maintenance of functional status. The nurse should also document teaching and referrals and prepare the patient for possible setbacks (Harrington, Estes, & Crawford, 2004). Community-based service providers are challenged to develop affordable and appropriate programs to assist older adults to remain in the home while maintaining their quality of life. Community-based services for older adults include home health care, community-based alternative programs, respite care, adult day care programs, senior citizen centers, homemaker programs, home-delivered meals, and transportation, among many others (Box 9–5). In some areas churches and neighborhoods have organized volunteer programs to help meet the needs of older adults who rarely leave home. Some of these programs rely on paid nurses and volunteers from the community. Functional status is a term used to describe an individual’s ability to perform the normal, expected, or required activities for self-care. It is a determinant of well-being and a measure of independence in older adults. Functional measures are much more useful in describing the service needs of older adults living in the community than are measures of acute and chronic illness. Because of their ability to predict service needs, functional measures are used to determine eligibility for many state-funded and federally funded community-based, long-term care programs. Physicians frequently order physical or occupational therapy as part of home health when there is a functional deficit (Mistiaen, Francke, & Poot, 2007). Functional status determines whether an older adult needs home health care or whether a home health client is recertified for home care services. The use of adaptive equipment, as well as barriers to the client’s function, should be noted. While assessing the client’s functional status, the home health nurse considers the client’s cognitive status, respiratory and cardiovascular status, and skin integrity. Deficits in these areas could impair the client’s ability to perform ADLs and IADLs safely. The client’s perception of self-care is also important because he or she could believe that no assistance is required when, in fact, a deficit exists (Mistiaen et al, 2007). For older adults, adapting to functional limitations is crucial for maintaining independence. The outcomes of severe functional impairments are costly (e.g., institutionalization). The home health nurse must assess for functional impairments. Early detection of limitations can lead to interventions that help preserve function and avoid more severe disability (Mistiaen et al, 2007). Cognitive impairment, which often affects an individual’s functional status, is another eligibility criterion used by various community programs. Cognitive status is assessed on admission and again with every skilled nursing visit. Other disciplines are also responsible for reporting a change in cognition to the nurse or case manager in home health. A change in cognitive status frequently signals a change in another body system (see Chapter 29). The home health nurse must establish a baseline assessment and be alert to deviations. Cognitive impairments can be reversible or irreversible, and home health personnel are in a key position to detect any changes. Although older adults prefer to live independently, it is not always possible or appropriate; financial status, functional status, and physical health may dictate consideration of alternative housing options that provide a more protective and supportive environment. Table 9–2 describes the most common housing options for older adults. Each option has its advantages and disadvantages. The decision about which option is most appropriate depends on such factors as the amount and type of assistance an older person requires, financial resources, geographic mobility, preferences for privacy and social contact, and the types of housing available. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) has several publications that describe each of these options in greater detail, including issues to consider when evaluating each option. TABLE 9–2 HOUSING OPTIONS FOR OLDER ADULTS Modified from American Association of Retired Persons (AARP): Tomorrow’s choices, Washington, DC, 1988, The Association; AARP: Your home, your choice, Washington, DC, 1984, The Association; and AARP: Staying at home: a guide to long-term care and housing, Washington, DC, 1992, The Association. Assessment of functional status aids in determining the type of services an older adult needs to remain in his or her home. A low score on a functional status test does not necessarily indicate the need for institutionalization, but it means that the older adult needs assistance with specific activities (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). The type of services needed, the availability of the services, the cost of the services, and the requirements to qualify for the services can be determined by a home health agency. Community services can be categorized into formal and informal services. Home health care is a short-term, formal service that provides assessment, observation, teaching, certain technical skills, and personal care. A client may receive home health care for a limited time and for a specific diagnosis. Homemaker services are another formal service. To qualify for most homemaker services, the older person must demonstrate a financial requirement and a specified need for service. Informal services include senior citizen centers, adult day care services, nutrition services, transportation services, and telephone monitoring services. Community resources, formal and informal, must meet the client’s needs (see Cultural Awareness Box). services, and determines whether there is a need for additional services (Rice, 2006). The major goal of the Older Americans Act (OAA) of 1965 was to remove barriers to independent living for older individuals and to ensure the availability of appropriate services for those in need. Through Title III, the Administration on Aging and state and community programs were designed to meet the needs of older adults, especially those at risk for loss of independence. The OAA established a national network of federal, state, and area Agencies on Aging (AAAs), which are responsible for providing a range of community services for older adults. States are divided into areas for planning and service administration. The OAA requires that each AAA designate community “focal points” as places where anyone in the community can receive information, services, and access to all of a community’s resources for older adults. Multipurpose senior citizen centers often serve as these focal points, but community centers, churches, hospitals, and town halls may also be designated as focal points. The types of services provided through the OAA and AAAs include information and referral for medical and legal advice; psychological counseling; preretirement and postretirement planning; programs to prevent abuse, neglect, and exploitation; programs to enrich life through educational and social activities; health screening and wellness promotion services; and nutrition services (Bales & Ritchie, 2009).

Health Care Delivery Settings and Older Adults

Characteristics of Older Adults in Acute Care

Characteristics of the Acute Care Environment

Risks of Hospitalization

Adverse Drug Reactions

Falls

Infection

Hazards of Immobility

Nursing in the Acute Care Setting

Nursing-Specific Competency and Expertise

Critical Care and Trauma Care

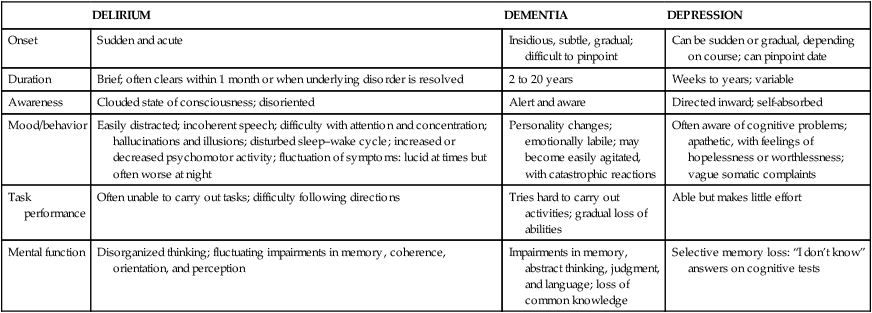

DELIRIUM

DEMENTIA

DEPRESSION

Onset

Sudden and acute

Insidious, subtle, gradual; difficult to pinpoint

Can be sudden or gradual, depending on course; can pinpoint date

Duration

Brief; often clears within 1 month or when underlying disorder is resolved

2 to 20 years

Weeks to years; variable

Awareness

Clouded state of consciousness; disoriented

Alert and aware

Directed inward; self-absorbed

Mood/behavior

Easily distracted; incoherent speech; difficulty with attention and concentration; hallucinations and illusions; disturbed sleep–wake cycle; increased or decreased psychomotor activity; fluctuation of symptoms: lucid at times but often worse at night

Personality changes; emotionally labile; may become easily agitated, with catastrophic reactions

Often aware of cognitive problems; apathetic, with feelings of hopelessness or worthlessness; vague somatic complaints

Task performance

Often unable to carry out tasks; difficulty following directions

Tries hard to carry out activities; gradual loss of abilities

Able but makes little effort

Mental function

Disorganized thinking; fluctuating impairments in memory, coherence, orientation, and perception

Impairments in memory, abstract thinking, judgment, and language; loss of common knowledge

Selective memory loss: “I don’t know” answers on cognitive tests

Special Care-Related Issues

Home Care and Hospice

Factors Affecting the Health Care Needs of Noninstitutionalized Older Adults

Functional Status

Cognitive Function

Housing Options for Older Adults

TYPE OF HOUSING

DESCRIPTION OF HOUSING

Accessory apartment

This is a self-contained apartment unit within a house that allows an individual to live independently without living alone. It generates additional income for older homeowners and allows older renters to live near relatives or friends and remain in a familiar community.

Assisted living facility (also called board and care home; personal care home; or sheltered care, residential care, or domiciliary care facility)

This is a rental housing arrangement that provides room, meals, utilities, and laundry and housekeeping services for a group of residents. Such facilities offer a homelike atmosphere in which residents share meals and have opportunities to interact. What distinguishes these facilities from simple boarding homes is that they provide protective oversight and regular contact with staff members. Some facilities offer additional services such as nonmedical personal care (e.g., bathing, grooming) and social and recreational activities. In many states these facilities operate without specific regulation or licensure; therefore the quality of service may vary greatly.

Congregate housing

Congregate housing was authorized in 1970 by the Housing and Urban Development Act. It is a group-living arrangement, usually an apartment complex, that provides tenants with private living units (including kitchen facilities), housekeeping services, and meals served in a central dining room. It is different from board and care facilities in that it provides professional staff such as social workers, nutritionists, and activity therapists who organize social services and activities.

Elder Cottage Housing Opportunity (ECHO)

This is a small, self-contained portable unit that can be placed in the backyard or at the side of a single-family dwelling. The idea was developed in Australia (where it is called a “granny flat”) to allow older adults to live near family and friends but still retain privacy and independence. ECHO units are distinct from mobile homes in that they are barrier-free and energy-efficient units specifically designed for older or disabled persons.

Foster home care

Foster care for adults is similar in concept to foster care for children. It is a social service administered by the state that places an older person who needs some protective oversight or assistance with personal care in a family environment. Foster families receive a stipend to provide board and care, and older clients have a chance to participate in family and community activities. Adult foster care is appropriate for older adults who cannot live independently but do not want or need institutional care.

Home sharing

Home sharing involves two or more unrelated people living together in a house or apartment. It may involve an older person and a younger person or two or more older people living together. The participants may share all living expenses, share rent only, or exchange services for rent. For the older homeowner, renting out a bedroom generates revenue that may make it possible to afford taxes and home expenses. Home sharing is viewed by many older adults as a practical alternative to moving in with adult children. Some communities provide house-matching programs, usually sponsored by local senior centers or the Area Agency on Aging.

Life care or continuing care retirement community (CCRC)

This is a facility designed to support the concept of “aging in place.” It provides a continuum of living arrangements and care—from assistance with household chores to nursing facility care—all within a single retirement community. Residents live independently in apartments or houses and contract with the community for health and social services as needed. If a resident’s need for health and nursing care prohibits independent living, the individual can move from a residential unit to the community’s health care unit or nursing facility. In addition to providing shelter, meals, and health care, a CCRC provides a variety of services and activities (e.g., religious services, adult education classes, library, trips, and recreational and social programs). The key attribute of a CCRC is that it guarantees a lifetime commitment to care of an individual as long as the person remains in the retirement community. The major disadvantage of a CCRC is that it can be expensive; most CCRCs require a nonrefundable entrance fee and charge a monthly assessment, which may increase.

Community-Based Services

Use of Community and Home-Based Services by Older Adults

Profile of Community- and Home-Based Services

Area Agencies on Aging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Health Care Delivery Settings and Older Adults

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access