In terms of health campaigns, fear appeals need to be used with some degree of caution. Too much fear can lead to such intense emotional reactions that people become too preoccupied with their fear to think rationally about steps they can take to avoid the threat (Dillard & Peck, 2000; Dillard et al., 1996; Stephenson & Witte, 2001). For example, a HIV/AIDS campaign that emphasizes death might produce such strong emotional reactions that individuals avoid thinking about the issue as a fear control response. This may prevent them from also thinking about ways in which they can reduce their susceptibility to the disease. Murray-Johnson and Witte (2003) advocate using high fear appeals only in cases where target audience members possess response efficacy, or the perceived ability to easily perform the recommended response behaviors promoted in the campaign. In addition, high fear appeals should be avoided with audiences who are already fearful of a threat since it can lead them to think less about the threat as a coping mechanism. In other cases the use of moderate fear appeals may be more appropriate to an audience (Hale & Dillard, 1995; Stephenson & Witte, 2001). Careful target audience analysis is needed to assess which type of fear appeal may be most effective for a specific population.

Stages of Change Models

Some researchers have developed theories of behavior change that take into account various stages of readiness that individuals pass through over time toward behavior change (Lippke & Ziegelmann, 2006; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984; Schwarzer, 1992). The advantage of this approach is that it assumes people may be in different stages when it comes to changing their health behaviors. A prominent stage theory is the transtheoretical model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984), which describes five stages of behavioral change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance/relapse. The HIV/AIDS pandemic is a helpful issue to illustrate this particular model, and examples from this crisis will be used to help explain it.

In the precontemplation stage, individuals are unaware of a health issue and subsequently do not think about making a behavioral change. For example, in the early 1980s many Americans were unaware of the looming threat of HIV/AIDS because it was not being widely discussed in the mass media, and consequently, most people did not consider changing their sexual behaviors. In the contemplation stage, people are aware of a health issue but may still be weighing the pros and cons of adopting some type of behavioral change. Once stories about HIV/AIDS and its relationship to safe sex gained prominence in the mid- to late 1980s, many people began to examine their own sexual behaviors. However, many heterosexual people still questioned whether they were really at risk for the disease since HIV/AIDS was first seen within the gay community and among intravenous drug users. Even though people were thinking about the disease, many people continued to practice unsafe sex. In the preparation stage, individuals actively begin planning to change their behavior. As more and more reports of heterosexual people and non-intravenous drug users began to surface in the media, many Americans felt they were ready to begin practicing safe sex. In the action stage, behavioral change actually occurs, such as when people started using condoms when having sex. Finally, the maintenance/relapse stage refers to whether people stick with their behavior change or relapse into one of the previous stages. Since the 1980s many people have continued to practice safe sex in an effort to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS.

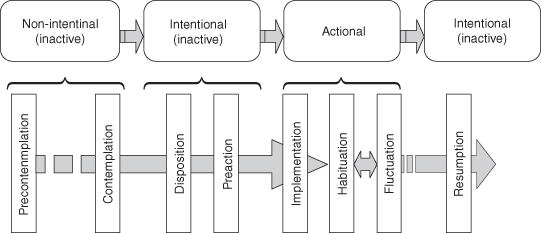

Lippke and Ziegelmann (2006) have proposed the multi-stage model of health behavior change (MSM), which extends the number of stages in the transtheoretical model (see Figure 10.2). Lippke and Ziegelmann distinguish between nonintentional inactive stages (precontemplation and contemplation) and the intentional (but still inactive) stages by adding the disposition stage, in which individuals implement certain goals for behavioral change, and the preaction stage, where people detail their plans for action. In addition, these researchers take into account the degree to which people stick to their behavioral changes (habituation), fluctuate, and resume behavioral changes following the decision to take action. When using stages of change models to plan a health campaign, campaign designers need to assess the various stages at which individuals within a target population may be in regarding the campaign health issue. For example, different types of messages need to be constructed for people in the precontemplative stage versus the maintenance/relapse stage. For people who are in the precontemplative stage, campaign messages should be directed toward raising awareness of the health issue and influencing perceptions of susceptibility to it. By contrast, audience members who are in the maintenance/relapse stage should be encouraged through campaign messages to continue engaging in preventive behaviors and warned against the threat of relapse.

The SOC model is useful to campaign designers for several reasons. First, individuals in different stages exhibit distinct behavioral characteristics. Thus, researchers can effectively analyze and segment a target audience according to their different stages of change. Then, practitioners can strategically design messages to move individuals through the stages. For example, if campaigners wish to design a campaign to promote a new service, and they determine that the majority of the members of the target population are in the contemplation stage, they can design messages to systematically move audience members through the preparation, action, and maintenance stages. Similarly, if the majority of the target audience is in the maintenance stage, educators can provide messages, which reinforce and support the desired behavior. This model has been empirically tested with numerous health topics, including cancer prevention behaviors, smoking cessation, sunscreen use, addictive behaviors, pregnancy prevention, and risky sexual behaviors.

Diffusion of Innovations

Rogers’ (2003) diffusion of innovations theory targets adoption of health innovations (i.e. an idea, behavior, technology, etc.) by defining characteristics of innovations that impact an individual’s decision to reject or adopt the innovation or behavior. If the health campaign is recommending the audience to adopt a new diet or getting a H1N1 flu shot, the message campaign would do well to incorporate what we have learned about the diffusion of innovations process. Specifically a health campaign must consider the following innovation attributes:

The Process of Conducting a Health Campaign

As we have seen, changing attitudes and beliefs about health and health-related behaviors can be extremely complex. Designing appropriate and effective messages that can lead to these goals in a health campaign requires a great deal of thought and planning. As we will discuss in more detail later in this chapter, the persuasion process greatly impacts what we should do in a health communication campaign. The first step in this process is to recognize that persuasion is a somewhat puzzling and often random process. However, for a message to be effective, a considerable number of events, thoughts, and behaviors must occur. For instance, the individual must be:

Obviously message failure at any point along these instances can result in failed behavioral outcomes. Therefore, a message campaign or a message strategy must be sure to address these issues. This section further explores some of the key steps and considerations when conducting a health campaign.

Audience Analysis

As with any attempt to inform or persuade a large group of people, health campaigns require a careful analysis of target audience characteristics. Having a thorough understanding of audience characteristics such as demographics, attitudes and beliefs, current behaviors, and reasons for current behaviors allows health campaign designers to appropriately segment audiences into smaller groups in order to produce messages that are appropriate to the characteristics of these subgroups within a target audience. As we will see, the greater the extent to which messages can be tailored to the characteristics of audience members, the more likely they will be to successfully influence attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Conducting Audience Analysis Research

Once a health campaign designer has decided upon a target audience for the campaign, he or she needs to conduct an audience analysis, or an assessment of a variety of characteristics of the audience members that are related to the campaign health issue, in order to gain a better understanding of how to influence them (Atkin & Freimuth, 2001). Analyzing a target audience typically requires research method skills, and while this topic is beyond the scope of this book, this section provides an overview of common ways in which campaign designers conduct target audience research. When conducting an audience analysis, campaign designers attempt to understand audience characteristics in a systematic way. The most common types of research methods for audience analysis are using available data, surveys, and interviews and focus groups. Each of these research methods is discussed below.

Using Available Data

In many cases information about target audience members already exists in the form of databases (Atkin & Freimuth, 2001). For instance, hospitals keep patient records, local and state governments compile health-related statistics about their regions, organizations keep employee records, and the federal government has databases about health-related variables through information provided on the US Census and through research efforts by organizations such as the CDC and the NIH. These databases allow campaign designers to examine characteristics of some target audiences without having to conduct primary research themselves. They can thus save campaign designers a great deal of time and money, since both are required to carry out interviews, focus groups, and surveys. However, these databases rarely contain all of the target audience characteristics that may be of interest to campaign designers. In addition, information gained from some databases can be dated (e.g. US Census data), and the information may no longer apply to the current target audience.

Surveys

Surveys are useful for collecting new information about a relatively large target audience through the use of questionnaires. Audience analysis surveys typically ask a variety of questions about audience demographics (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, income), current health-related behaviors, attitudes and beliefs about health, efficacies and skills, and a variety of other questions that may help the campaign designer to better understand what will meet audience members’ health needs and motivate them toward achieving the campaign goals (Atkin & Freimuth, 2001). Survey researchers rarely disseminate questionnaires to an entire target population because most populations are either too large or difficult to reach. Instead, audience researchers conduct surveys using a sample of individuals who are representative of the larger population, and they make inferences about the larger population based upon the findings from the sample.

A key aspect of samples is that they should be representative of the larger target population as much as possible. One way to be more confident about how representative a sample is of a population is to use a probability sample. Sampling is the process of obtaining a sample for a survey, and probability sampling involves randomly selecting participants for a sample from a sample frame, or list of population members. Each population member is given a number, and researchers use random number tables or random numbers generated by a computer to select certain numbers (and subsequently people) into the sample. It can be very difficult to find a sampling frame for many larger populations.

In many cases probability sampling is too difficult to accomplish, and researchers have to engage in nonprobability sampling, such as convenience samples (e.g. finding anyone who is willing to participate in the survey). When using a nonprobability sample, campaign designers need to be careful when segmenting the target audience based upon sample data results. However, in these cases, using a nonprobability sample is better than not conducting an audience analysis at all.

Interviews and Focus Groups.

Interviews and focus groups are excellent methods for gaining a thorough understanding of target audiences’ perceptions of a health issue and their health-related needs (Slater, 1995). Interviews and focus groups involve talking to a sample of target audience members and asking them various questions about their thought processes and behaviors relating to the campaign health issue. Interviews involve talking to individual audience members, whereas focus groups are group interviews with typically eight to ten people. When conducting interviews with individuals or within focus groups, it is important to try to make participants feel relaxed. The researcher should obtain informed consent, or permission from the participants after they have been informed about the purposes and potential risks of the study, prior to starting an interview or focus group. Focus groups should occur in comfortable surroundings, and the facilitator of the focus group should be skilled at getting people to express their opinions.

One advantage of focus groups over interviews is that one person’s responses during a focus group can remind another participant of similar experiences or feelings with a health issue, and this can add to the richness of the data by allowing researchers to obtain multiple viewpoints on the subject. However, some individuals are more apprehensive about speaking up in a focus group compared to a one-on-one interview because they may feel that others in the group will judge them if they express a viewpoint. In addition, some individuals in groups tend to dominate the discussion, and this may take time away from other participants who are more reticent. Focus group facilitators should attempt to intervene in such situations and try to get all members of the group to talk if possible.

In addition, the researcher should ask participants’ permission to tape record or videotape the interview or focus group. This will provide a record of the participant responses for data analysis. Videotape offers researchers the advantage of being able to assess nonverbal cues from participants that can give insights into how people feel about certain topics being discussed. Videotaping can be even more valuable for recording interactions during focus groups because it is often difficult to distinguish one participant from another on an audiotape. However, the researcher should protect the anonymity of all participants by using pseudonyms during the interview or focus group and when transcribing content from audio and videotape recordings, and the tapes should be stored in a locked facility so that people other than the researcher and his or her associates cannot access them.

Audience Segmentation

Audience segmentation is the process of dividing the larger target audience population into smaller subgroups of individuals based upon some meaningful criteria (Rimal & Adkins, 2003; Slater, 1995), usually the demographic, psychological, and behavioral characteristics that were assessed during the audience analysis. Because people often differ considerably on these characteristics, it is difficult to design campaign messages that will influence an entire target population. Thus, the purpose of audience segmentation is to help maximize the impact of campaign messages. Generic health campaign messages (messages that apply to the majority of the population) tend to have limited impact on target audiences (Atkin & Freimuth, 2001), but more specific messages (i.e. messages tailored to unique characteristics of subgroups of the target population) tend to be much more effective in influencing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Rimal & Adkins, 2003).

For example, communication researchers at the University of Kentucky have had a great deal of success segmenting audiences based on a psychological variable known as sensation seeking (Everett & Palmgreen, 1995; Palmgreen & Donohew, 2003; Palmgreen, Donohew, & Harrington, 2001). High sensation seekers are individuals who enjoy taking risks as well as vivid, exciting, and novel experiences, for example, people who like to bungee jump, sample exotic foods, and those who “like to live dangerously.” In contrast, low sensation seekers tend to prefer mundane, everyday types of experiences, and they often feel more comfortable “playing it safe.” According to Palmgreen, Donohew, & Harrington (2001), “high sensation seekers (HSSs) also have distinct and consistent preferences for particular kinds of messages based on their needs for the novel, the unusual, and the intense” (p. 301). For example, high sensation seekers like messages that are fast-paced and exciting, use close-up shots and music, and advertisements that employ rapid cutting. Using the SENTAR approach (a campaign approach based upon sensation-seeking tendencies), Palmgreen and associates have been successful in designing antidrug messages that appeal to high sensation seekers (who tend to be at high risk for drug abuse, risky sexual practices, and other negative health-related behaviors) and that have led to reductions in self-reported drug use.

Of course, sensation seeking is just one of many variables that can be used to segment target audiences. Other variables that can be used include (i) demographics (e.g. sex, race, socioeconomic status); (ii) psychological variables (e.g. health beliefs, psychological tendencies, attitudes, values); and (iii) health-related skills. Audience analysis and health-related theories play a crucial role in determining key variables that can be used to segment subgroups of target audiences. Segmentation helps campaign designers to maximize the potential of a campaign to influence positive health outcomes and to gain a careful understanding of important variables that can be used to improve the impact of future health campaigns.

Creating Message Content

Much of what appears in the specific content of messages during a health campaign is influenced by the characteristics of the target audience and the health issue itself. However, there are variables and considerations common to message content design in most campaigns that campaign designers should be familiar with. According to Salmon and Atkin (2003), “campaigns utilize three general communication processes to move a target audience toward a desired response: awareness, instruction, and persuasion” (p. 455). This section explores these aspects of message design and other important message content features, including gaining audience members’ attention, variables associated with motivating audience members to action, and variables associated with the perceived personal and social resources for changing attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors among target audience members.

Gaining Audience Members’ Attention and Motivating Them to Action

Health campaign message designers have to compete with many other types of messages in society, including advertisements, news, and entertainment (Murray-Johnson & Witte, 2003; Parrott, 1995; Salmon, 1989). Through the use of theoretical models of changing health-related cognitions and behaviors and a careful audience analysis, campaign designers can often identify key variables that have a high probability of motivating their target audience. Drawing on the health belief model, Murray-Johnson and Witte (2003) argue that campaign messages should contain cues to action, or message features that prompt individuals to pay attention to the content of messages. Recall from earlier in the chapter that cues to action are needed to trigger motivation, and they can be developed from sources internal to audience members, such as guilt or fear, or external sources, such as using credible spokespersons (e.g. the Surgeon General) to motivate change. During the audience analysis, campaign designers can assess the salience of certain types of messages, or the perceived importance of messages to audience members. Variables such as the perceived severity of a health threat, perceived susceptibility, and attitudes, beliefs, values, and perceived resources surrounding a health issue all influence the salience of messages.

Vividness, repetition, and how messages are placed in the media are also important factors in message design (Murray-Johnson & Witte, 2003). Vivid messages, such as messages that contain more exciting, colorful, or detailed images and/or audio cues, may motivate change because they are more memorable than less vivid messages. In addition, campaign messages that are novel or unexpected tend to motivate audience member involvement (Parrott, 1995). Repetition of messages can also stimulate motivation, and campaign designers should consider repeating key messages several times within campaign materials. Ideal placement of campaign messages should also be assessed during campaigns. Campaign designers can assess how target audience members respond to messages that vary in terms of vividness and repetition during the audience analysis phase of the campaign. Placement deals with where target audience members are most likely to see the message, and assessing ideal placement during the audience analysis phase helps campaign designers decide which media are best suited for disseminating the campaign messages.

Persuasive Message Appeals

There are a number of issues that campaign designers need to consider when constructing persuasive appeals for a health campaign. Individuals vary considerably in terms of the types of messages that influence their cognitions and behaviors.

Some individuals are influenced by messages emphasizing credibility, or the extent to which message content is believed to be accurate, and it is typically conveyed by the trustworthiness and competence of the person delivering the campaign message and through convincing evidence for a persuasive argument (Salmon & Atkin, 2003). According to Salmon and Atkin (2003), the campaign messenger, or the person who provides information and testimonials or demonstrates appropriate behaviors during a health campaign, is crucial in enhancing the message’s credibility. Salmon and Atkin contend that when selecting a campaign messenger, he or she will be more credible and attractive (and subsequently more persuasive) to a target audience if he or she exhibits expertise, trustworthiness, familiarity, interpersonal attractiveness, and similarity to the target audience.

The messenger can be any person capable of conveying these characteristics to the target audience and does not necessarily need to be a celebrity, although for certain target audiences a celebrity such as Magic Johnson speaking about HIV/AIDS might embody these characteristics. Celebrity messengers can sometimes produce negative effects for a campaign, especially when stories emerge within popular media about their lifestyles or other controversial information that can undermine the campaign message. However, physicians, specialists, cancer survivors, and many other types of individuals may be good candidates for a campaign messenger. In addition to the campaign messenger, the credibility of a campaign can be enhanced by using evidence for cognitive and/or behavioral change that comes from credible sources, such as studies from established scientific journals (e.g. Journal of the American Medical Association) or trusted government sources (e.g. the CDC).

Other audiences are influenced by logical appeals, or persuasive messages that provide logical and convincing evidence for change, while others are influenced by emotional appeals, such as messages that emphasize strong emotions such as fear. Some researchers have found that messages that influence positive emotions in health campaigns, such as positive imagery and mood, tend to increase attention to messages, recall, positive attitudes, and compliance to recommended behaviors (Monahan, 1995). Less is known about other types of positive affect strategies in health campaigns, such as the use of humor. However, it appears that positive affect appeals tend to reduce psychological reactance, or the tendency of people to disregard messages that they find threatening or offensive.

When constructing campaign messages using these appeals, designers again need to consider many characteristics of the target audience that are found to be relevant during formative research and audience analysis procedures. For example, highly educated audiences may be more persuaded than less educated audiences by statistics or certain types of logical argument. For more educated audiences, two-sided persuasive messages, or messages that contain and refute counterarguments for the proposed behavioral change, may be more influential than one-sided messages (Salmon & Atkin, 2003). Depending upon the audience, emphasizing positive (e.g. health benefits) and/or negative (e.g. symptoms of a disease) incentives for change may be equally effective. One approach that draws upon presenting multiple arguments within a health campaign message is inoculation theory (McGuire, 1970; Pfau, 1995). Essentially, inoculation involves presenting audience members with weak arguments that are contrary to the goals of the campaign (e.g. reasons for drinking in an anti-drinking campaign) along with information that refutes these arguments. When these types of efforts are successful, target audience members are said to be inoculated to the influence of messages that run counter to the goals of the campaign. For example, a college student who has been exposed to a variety of arguments against binge drinking may be more likely to resist attempts by peers to engage in such behaviors.

In recent years, health communication scholars and health practitioners have utilized prospect theory by using message framing as a way to understand the communication involved in risky decisions (see, e.g. Kahneman & Tversky, 1979, 2000; Sparks, 2012; Sparks & Turner, 2008; Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). The landmark essays of Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman resulted in prospect theory, which suggests that individuals will react differentially to information presented as gains or losses. People encode information relevant to choice options in terms of potential gains or potential losses. Thus, factually equivalent information can be presented to people differently so that they encode it as either a gain or a loss (framing). A framing effect is demonstrated by constructing two transparently equivalent versions of a given problem, which nevertheless yield predictably different choices. The standard example of a framing problem, which was developed quite early, is the “lives saved, lives lost” question, which offers a choice between two public health programs proposed to deal with an epidemic that is threatening 600 lives: one program will save 200 lives, the other has a 1/3 chance of saving all 600 lives and a 2/3 chance of saving none. In this version, people prefer the program that will save 200 lives for sure. In the second version, one program will result in 400 deaths, the other has a 2/3 chance of 600 deaths and a 1/3 chance of no deaths. In this formulation most people prefer the gamble. Of course, these formulations present identical situations. The only difference is that in the first formulation the problem is framed in terms of lives saved, and in the second the situation is framed as a matter of lives lost. Thus, the message frame that a decision-maker adopts is controlled partly by the formulation of the problem and partly by the norms, habits, and personal characteristics of the decision-maker (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981, p. 453). Nearly all health-related information can be construed in terms of either gains (benefits) or losses (costs). For example, a gain-framed message would say that obtaining a mammogram allows tumors to be detected early, which maximizes treatment options. In contrast, the same message framed as a loss would say that if you do not obtain a mammogram, tumors cannot be detected early, which minimizes your treatment options. Thus, which frame works better?

The answer depends on whether the target health behavior is an illness detection behavior or an illness protection behavior (Rothman & Salovey, 1997). Detection behaviors (e.g. prostate exam) involve uncertainty—that is, you may find a problem! Protection behaviors (e.g. using sunscreen) typically lead to relatively certain outcomes—that is, you maintain your current healthy status.

The message-framing component of prospect theory has been utilized in health risk studies dealing with the uncertainty and risks involved in disease detection (Sparks, 2012). Prospect theory predicts that loss-framed information leads to preference for uncertainty, whereas gain-framed information leads to preference for certainty. Research findings indicate that loss-framed messages were effective in promoting mammography, breast self-examinations, and HIV testing. Gain-framed messages were effective in promoting infant car restraints, physical exercise, smoking cessation, and sunscreen.

Other Message Considerations

Snyder and Hamilton (2002) examined the impact of several message characteristics in a wide variety of health-related campaigns. These researchers found that for some types of campaigns, especially health-related issues that have legal ramifications, such as driving under the influence, abuse of controlled substances like Oxycontin, and seat belt usage, enforcement messages, or messages that emphasize negative repercussions (e.g. fines, arrests) to target audience members as a result of not following laws, may be effective in motivating behavioral change. Snyder and Hamilton found that campaigns using enforcement messages influenced target audience members more than campaigns that did not include these types of messages. In addition, campaigns using messages that give audiences new reasons to change their behavior (e.g. new information about the importance of getting a mammogram) were more influential in terms of behavioral change than campaigns that relied on older information about a health topic.

Channels and Message Dissemination Processes

One important consideration in designing a health campaign is the type of channel that will be used to disseminate the campaign message(s). Traditionally, health campaign designers have relied on traditional mass media when delivering campaign messages, such as television, radio, and print material (Atkin, 2001). In recent years researchers have started to investigate the efficacy of new media for disseminating health campaign messages, such as cell phones and the Internet. This section examines a number of different channel characteristics that have important implications for health campaign design.

Targeting is the process of selecting the best communication channel for disseminating a message (Rimal & Adkins, 2003). Again using information from the audience analysis, campaign designers need to make decisions about which channel or channels are appropriate for reaching and influencing the target audience. For example, campaign designers need to consider where target audience members are most likely to see campaign messages, the type of media they use, the ability of a channel to support specific types of messages, audience literacy levels, and the potential impact of various channels.

Some target audiences may be more likely to see television or radio messages, while other audiences are more likely to be exposed to a message when it comes to them through billboards, Internet advertisements, or interpersonal channels (e.g. peer group members). Among low literacy audiences, radio and television campaigns may be more influential than printed materials because radio and television can transcend the written word through audio messages and/or images that convey a message without words. Snyder and Hamilton (2002) found that campaigns with greater reach, or a higher percentage of people being exposed to the campaign message, were more influential in changing target audience behaviors than campaigns with a more limited reach. Messages on television and radio tend to have greater reach than messages disseminated through other channels. However, television and radio messages are typically more generic than printed materials or messages delivered in person (which are less expensive to produce and can be changed more easily for different segments of the target audience).

As we have seen, tailored messages tend to have greater impact than generic messages in campaigns. This aspect has to do with specification, or the ability of a channel to influence certain subgroups within the population (Atkin, 2001). In addition, using channels such as the Internet or a dialogue between a community spokesperson and target audience members in a face-to-face meeting invites greater audience participation and involvement than radio or television advertisements. All of these features of channels, as well as the cost and efficiency of the channel, need to be assessed by campaign designers (Salmon & Atkin, 2003).

However, researchers have recently been paying more attention to multi-pronged approaches to health campaigns. These advocate an interpersonal theory-based approach to changing health behaviors when it is appropriate and possible to implement (Rogers, 2003; Sparks, 2012), particularly with specialized populations that do not use mediated sources, such as older adults and those from cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds with little access to technologies (Sparks & McPherson, 2007; Sparks & Turner, 2008). Health behavior and health communication scholars study messages and interventions that encourage patients to be active participants in health communication contexts. In addition to designing mediated health messages, researchers are also focusing on effective interpersonal message strategies that will prove effective given the unique complexities and barriers patients and their family members often face (see, e.g. Sparks, 2007). Researchers can no longer ignore the unique cognitive and emotional processes different populations often experience. Interpersonal messages are more likely to reach such specific populations, one patient and one family at a time (Sparks, 2007, 2008).

As we have seen, while it is always possible to create a more generalized or generic message that will be communicated to an audience, generalized messages often lack the impact of more specific messages. Traditionally, health campaign materials have been generic, and the creators of campaign messages have attempted to provide as much information as possible within a single communication without considering the specific characteristics of an audience (Kreuter & Wray, 2003; Kreuter, Farrell, Olevitch, & Brennan, 2000; Strecher, Rimer, & Monaco, 1989). However, tailored health messages, or messages designed to influence specific subgroups of a target audience based on individual member characteristics (Rimal & Adkins, 2003), tend to be more effective than generic messages in influencing cognitive and behavioral changes in target audiences (Davis et al., 1992; Kreuter, Oswald, Bull & Clark, 2000; Rimal & Adkins, 2003; Rosen, 2000; Sparks & Turner, 2008).

According to Salmon and Atkin (2003), “a typical health campaign might subdivide the population on a dozen dimensions (e.g. age, ethnicity, stage of change, susceptibility, self-efficacy, values, personality characteristics, and social context), each with multiple levels” (p. 453). In many cases, while it is possible to segment target audiences into literally thousands of subgroups, the majority of health campaigns create substantially fewer groups, due to financial and logistical constraints. Yet, even segmenting audiences into relatively few small subgroups can increase the precision of messages over generic messages.

It is now possible to create personalized messages in a health campaign through the use of computer programs (Kreuter, Farrell et al., 2000) that use algorithms to match the characteristics of each individual in a target audience to a specific, individually tailored message. However, this method can increase the complexity and cost of a campaign. In addition, according to Schooler, Chaffee, Flora, and Roser (1998), there is always a tradeoff between the specificity of a health message and its reach. In other words, generic messages tend to have greater reach than tailored messages, which means that because the message is more generalized it can appeal to greater numbers of individuals who are exposed to it than tailored messages. Tailored messages, on the other hand, provide more specific information, but they may have limited reach because they are so specialized.

Atkin (2001) pinpoints a variety of other channel considerations when designing health campaigns. These include accessibility of the channel for the target audience (e.g. some individuals may have limited access to the Internet), depth, or the ability of the channel to convey complex information, economy, or the cost of using a particular channel, and efficiency, or the amount and quality of information a channel can deliver vis-à-vis the cost of using it. As you can see, there are many decisions a health campaign designer needs to make regarding the most appropriate and useful channel for the target audience.

Formative Campaign Evaluation

As we have seen, the process of creating a health campaign can be complex, especially when dealing with certain health issues and hard-to-influence audiences, and this may lead to many things that can potentially go wrong with a campaign. Larger campaigns can be quite expensive given the amount of time that is needed to analyze the audience, the cost of creating campaign materials, and the cost of using different media. Therefore, it is important for campaign designers to take measures to minimize possible campaign shortcomings. One way to identify and potentially minimize problems prior to launching a campaign is to engage in formative campaign evaluation (Atkin & Freimuth, 2001; Valente, 2002). Formative campaign evaluation research refers to the activities conducted prior to the start of a campaign. Valente (2002) outlines the objectives and the specific research activities that are important during the formative evaluation stage. Objectives in this stage include (i) understanding the target audience’s barriers to action; (ii) learning the appropriate language to develop messages; and (iii) developing a conceptual model. Specifically, focus group discussions and/or in-depth interviews are conducted to determine knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of the target population. This is particularly important prior to message development because evaluation data are useful in identifying target audience characteristics and predispositions, specifying intermediate response variables and behavioral outcomes, assessing channel exposure patterns, and determining receptivity to potential message components (Atkin & Marshall, 1996).

There are many ways that health campaigns can be evaluated, including some of the research methods that are mentioned in the section on audience analysis procedures in this chapter. Available data, interviews, focus groups, and surveys can all be used to assess the degree to which campaign goals were met, although these methods are not without limitations.

Pilot Testing

By using a sample of the target population, campaign designers can gauge what aspects of the campaign work and do not work with a group of people who are similar to the larger population. When obtaining feedback about the campaign from the pilot sample, campaign designers should measure the degree to which the campaign messages led to cognitive and/or behavioral changes in the group, and potential problems with the campaign, such as determining whether messages were noticed, salient, or understandable to the audience, reasons why some people may not have been influenced by the messages, and the appropriateness of the spokesperson, medium, and message content.

Launching the Campaign, Process Evaluation, and Outcome Evaluation

After making additional adjustments to campaign messages following formative evaluation and pilot testing, campaign designers are then ready to launch the campaign. The length of a health campaign will largely depend upon the goals of the campaign, such as if the campaign is targeting awareness about a health issue or behavioral outcomes related to it, the budget and resources available to the campaign designers, and other pragmatic issues, such as the amount of time that campaign designers can devote to it.

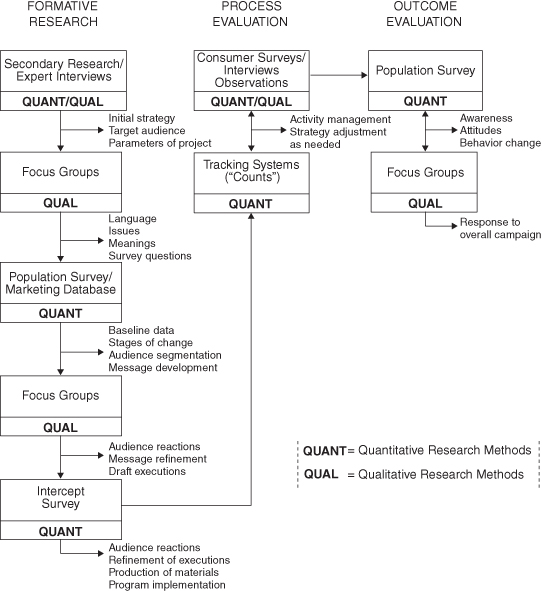

Determining whether or not a campaign is successful can be assessed by conducting outcome evaluation research. However, the question of why a campaign was or was not successful requires process evaluation research. Evaluation is widely understood to be conducted as a set of stages that require the systematic application of research procedures to assess the conceptualization, design, implementation, and utility of intervention programs (Rossi & Freeman, 1993; Shadish, Cook, & Leviton, 1991; Valente, 2002). Health campaign planners and researchers can rely on program evaluation strategies for assessment and improvement to inform future campaigns. In addition, evaluations serve as a means by which campaign planners and funding agencies can determine the effectiveness of a health campaign’s promotion activities or treatments. Process evaluations tend to be easier to design and conduct when the campaign approach is derived from a strong theoretical framework. According to Valente (2002), “theory specifies how these factors relate to one another by constructing a conceptual model of the process of behavioral change” (p. 30). Ideally, campaign designers should integrate formative, process, and outcome evaluations into the campaign design (see Figure 10.3).

Figure 10.3 Integrative social marketing research model.

Source: Weinreich, 2010.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree