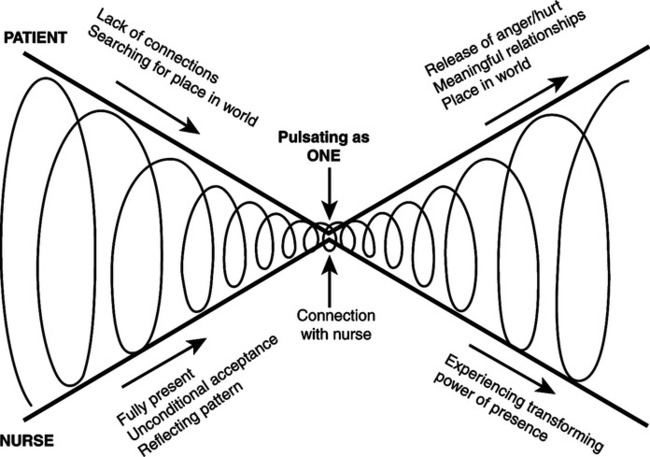

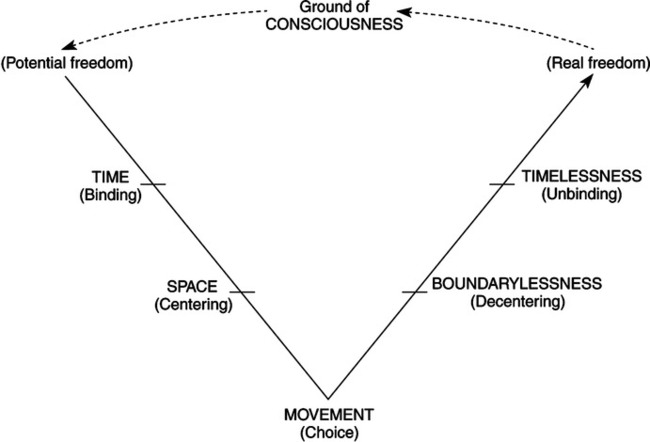

Margaret A. Newman was born on October 10, 1933, in Memphis, Tennessee. She earned a bachelor’s degree in home economics and English from Baylor University in Waco, Texas, and a second bachelor’s degree in nursing from the University of Tennessee in Memphis (M. Newman, curriculum vitae, 1996). Her master’s degree in medical-surgical nursing and teaching was received from the University of California, San Francisco. In 1971, she earned her PhD in nursing science and rehabilitation nursing from New York University in New York City. Newman has presented many papers on topics pertaining to her theory of health as expanding consciousness. She published Theory Development in Nursing (1979), Health as Expanding Consciousness (1986, 1994), A Developing Discipline: Selected Works of Margaret Newman (1995a), and Transforming Presence: The Difference That Nursing Makes (2008). She has written numerous journal articles and book chapters. In 1986, she did a case study analysis of practice at three sites within the Minneapolis-St. Paul area and discussed conclusions concerning changes necessary for hospital nursing practice (Newman & Autio, 1986). From 1986 to 1997, Newman investigated sequential patterns of persons with heart disease and cancer in relation to the theory of health as expanding consciousness (Newman, 1995c; Newman & Moch, 1991). Other publications reflect her passion for integration of nursing theory, practice, and research, evolving viewpoints on trends in philosophy of nursing and analysis of theoretical models of nursing practice and nursing research (Newman, 1992, 1997b, 1999, 2003). During 1989 and 1990, Newman was principal investigator of a project that explored the theory and structure of a professional model of nursing practice at Carondelet St. Mary’s Community Hospitals and Health Centers in Tucson, Arizona (Newman, 1990b; Newman, Lamb, & Michaels, 1991). Newman emphasizes the primacy of relationships as a focus of nursing, both nurse-client relationships and relationships within clients’ lives (Newman, 2008). During dialectic nurse-client relationships, clients get in touch with the meaning of their lives through identification of meanings in the process of their evolving patterns of relating (Newman, 2008). “The emphasis of this process is on knowing/caring through pattern recognition” (Newman, 2008, p. 10). Insight into these patterns provides clients with illumination of action possibilities, which then opens the way for transformation (Newman, 1990a). The nurse facilitates pattern recognition in clients by forming relationships with them at critical points in their lives and connecting with them in an authentic way. The nurse-client relationship is characterized by “a rhythmic coming together and moving apart as clients encounter disruption of their organized, predictable state” (Newman, 1999, p. 228). She further states that the nurse will continue to connect with clients as they move through periods of disorganization and unpredictability to arrive at a higher, organized state (Newman, 1999). The nurse comes together with clients at these critical choice points in their lives and participates with them in the process of expanding consciousness. The relationship is one of rhythmicity and timing, with the nurse letting go of the need to direct the relationship or fix things. As the nurse relinquishes the need to manipulate or control, there is a greater ability to enter into this fluctuating, rhythmic partnership with the client (Newman, 1999). Newman has diagrammed this nurse-client interaction of coming together and moving apart through the processes of recognition, insight, and transformation (Figure 23-1) Nurses are seen as partners in the process of expanding consciousness, and are transformed and have their lives enhanced in the dialogical process (Newman, 2008). As a facilitator, the nurse helps an individual, family, or community to focus on patterns of relating (M. Newman, telephone interview, 2004). The nursing process is one of pattern recognition. Newman’s early suggestion (Newman, 1995b) was that the NANDA health assessment framework, based on unitary person-environment patterns of interaction, be used to facilitate clients’ pattern recognition (Roy, Rogers, Fitzpatrick, Newman, & Orem, 1982). At the time, the patterns were intended to guide nurses to make holistic observations of “person-environment behaviors that together depict a very specific pattern of the whole for each person” (Newman, 1995b, p. 261). Newman (2008) has since emphasized concentrating on what is most meaningful to clients in their own stories and patterns of relating. Within the theory, the role of the nurse in nurse-client interactions is seen as a “caring, patternrecognizing presence” (Newman, 2008, p. 16). The nurse perceives patterns in client’s stories or sequences of events, and the pattern of the individual changes with the new information. According to Newman (2008), it is important for nurses to view clients’ stories comprehensively. Through active listening, nurses can enter the whole through the parts and intuit the whole from the pattern. Differences are viewed as part of a unified whole. The nurse can facilitate client insight through sharing the process of pattern recognition, thus opening action possibilities (Newman, 1987b). Persons as individuals are identified by their individual patterns of consciousness (Newman, 1986). Persons are further defined as “centers of consciousness within an overall pattern of expanding consciousness” (Newman, 1986, p. 31). The definition of persons has also been expanded to include family and community (Newman, 1994). Although environment is not explicitly defined, it is described as being the larger whole, which contains the consciousness of the individual. The pattern of person consciousness interacts within the pattern of family consciousness and within the pattern of community interactions (Newman, 1986). A major assumption is that “consciousness is coextensive in the universe and resides in all matter” (Newman, 1986, p. 33). Client and environment are viewed as unitary evolving patterns (Newman, 2008). Health is the major concept of Newman’s theory of expanding consciousness. A fusion of disease and non-disease creates a synthesis that is regarded as health (Newman, 1979, 1991, 1992). Disease and non-disease are each reflections of the larger whole; therefore, a new concept of health, “pattern of the whole,” is formed (Newman, 1986, p. 12). Newman (1999) has further elaborated her view of health by stating that “health is the pattern of the whole, and wholeness is” (p. 228). Further, this wholeness cannot be gained or lost. Within this perspective, becoming ill does not diminish wholeness, but wholeness takes on a different form. Newman (2008) has stated that pattern recognition is the essence of emerging health. “Manifest health, encompassing disease and non-disease can be regarded as the explication of the underlying pattern of person-environment” (Newman, 1994, p. 11). Therefore, health and evolving pattern of consciousness are the same. Specifically, health is viewed “as a transformative process to more inclusive consciousness” (Newman, 2008, p. 16). The theory, Health as Expanding Consciousness, stems from Rogers’ (1970) science of unitary human beings. Rogers’ assumptions regarding wholeness, pattern, and unidirectionality are the foundation of Newman’s theory (M. Newman, personal correspondence, 2004). Hegel’s process of the fusion of opposites (Acton, 1967) helped Newman to conceptualize the fusion of health and illness into a new concept of health. Bentov’s (1977) explication of life as the process of expanding consciousness prompted Newman to assert that this new concept of health is the process of expanding consciousness (M. Newman, personal correspondence, 2004). Bohm’s (1980) theory of implicate order supports Newman’s postulate that disease is a manifestation of the pattern of health. Newman (1994) stated that she began to comprehend “the underlying, unseen pattern that manifests itself in varying forms, including disease, and the interconnectedness and omnipresence of all that there is” (p. xxvi). Young’s (1976) theory of human evolution pinpointed the role of pattern recognition for Newman. She explained that Young’s ideas provided the impetus for her efforts to integrate the basic concepts of her new theory, movement, space, time, and consciousness, into a dynamic portrayal of life and health (Newman, 1994). Further, Moss’ (1981) experience of love as the highest level of consciousness was important to Newman in providing affirmation and elaboration of her intuition regarding the nature of health (Newman, 1994). Newman also incorporated Prigogine’s (1976) theory of dissipative structures as an explanation for the timing of nursing presence as the patient fluctuates from one level of organization to a higher level (M. Newman, personal correspondence, 2004). Although Newman (1997a) acknowledges the contributions of these theories to her theory, she has stated that her theory “was enriched by them, but was not based on them” (p. 23). Evidence for the theory of health as expanding consciousness emanated from Newman’s early personal family experiences. Her mother’s struggle with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and her dependence on Newman, then a young college graduate, sparked an interest in nursing. From that experience evolved the idea that “illness reflected the life patterns of the person and that what was needed was the recognition of that pattern and acceptance of it for what it meant to that person” (Newman, 1986, p. 3). Research has been conducted on the theoretical sources (Newman, 1987b). In 1979, Newman wrote that in order for nursing research to have meaning in terms of theory development, it must have three components. These components are as follows: (1) having as its purpose the testing of theory, (2) making explicit the theoretical framework upon which the testing relies, and (3) reexamining the theoretical underpinnings in light of the findings (Newman, 1979). She believed that if health is considered an individual personal process, research should focus on studies that explore changes and similarities in personal meaning and patterns. The foundation for Newman’s assumptions (M. Newman, telephone interview, 2000) is her definition of health, which is grounded in Rogers’ 1970 model for nursing, specifically, the focus on wholeness, pattern, and unidirectionality. From this, Newman developed the following assumptions that support her theory to this day (Newman, 2008). 1. Health encompasses conditions heretofore described as illness or, in medical terms, pathology… 2. These “pathological” conditions can be considered a manifestation of the total pattern of the individual… 3. The pattern of the individual that eventually manifests itself as pathology is primary and exists prior to structural or functional changes… 4. Removal of the pathology in itself will not change the pattern of the individual… 5. If becoming “ill” is the only way an individual’s pattern can manifest itself, then that is health for that person… From these assumptions, Newman set forth the thesis: Health is the expansion of consciousness (Newman, personal correspondence, 2008). Newman’s implicit assumptions about human nature include being unitary, being an open system, being in continuous interconnectedness with the open system of the universe, and being continuously engaged in an evolving pattern of the whole (M. Newman, telephone interview, 2000). She views unfolding consciousness as a process that will occur regardless of what actions nurses perform. However, nurses can assist clients in getting in touch with what is going on and, in that way, can facilitate the process (Newman, 1994). Early writings focused heavily on the concepts of movement, space, time, and consciousness. In Theory Development in Nursing, Newman (1979) delineated the relationships between movement, space, time, and consciousness. One proposition was that there was a complimentary relationship between time and space (Newman, 1979, 1983). Examples of this relationship were given at the macrocosmic, microcosmic, and humanistic (everyday) levels. At the humanistic level, highly mobile individuals live in a world of expanded space and compartmentalized time. There is an inverse relationship between space and time in that when a person’s life space is decreased, such as by physical or social immobility, then that person’s time is increased (Newman, 1979). Movement is a “means whereby space and time become a reality” (Newman, 1983, p. 165). Humankind is in a constant state of motion and is constantly changing internally (at the cellular level) and externally (through body movement and interaction with the environment). This movement through time and space is what gives humankind a unique perception of reality. Movement brings change and enables the individual to experience the world (Newman, 1979). Movement was also referred to as a “reflection of consciousness” (Newman, 1983, p. 165). It is the means of experiencing reality and also the means by which an individual expresses thoughts and feelings about the reality of experiences. An individual conveys awareness of self through the movement involved in language, posture, and body movement (Newman, 1979). An indication of the internal organization of a person and of that person’s perception of the world can be found in the rhythm and pattern of the person’s movement. Movement patterns provide additional communication beyond that which language can convey (Newman, 1979). The concept of time is seen as a function of movement (Newman, 1979). This assertion was supported by Newman’s (1972) studies of the experience of time as related to movement and gait tempo. Newman’s research demonstrated that the slower an individual walks, the less subjective time is experienced. However, when compared with clock time, time seems to “fly.” Although individuals who are moving quickly subjectively feel that they are “beating the clock,” they report that time seems to be dragging when checking a clock (Newman, 1972, 1979). Time is also conceptualized as a measure of consciousness (Newman, 1979). Bentov (1977) measured consciousness with a ratio of subjective to objective time and proposed this assertion. Newman applied this measure of consciousness to subjective and objective data from her research. She found that the consciousness index increased with age. Some of her research has also supported the finding of “increasing consciousness with age” (Newman, 1982, p. 293). Newman cited this evidence as support for her position that the life process evolves toward consciousness expansion. However, she asserted that certain moods, such as depression, might be accompanied by a diminished sense of time (Newman & Gaudiano, 1984). As the theory evolved, Newman developed a synthesis of the pattern of movement, space, time, and consciousness (M. Newman, personal correspondence, 2004, 2008). Time was not merely conceptualized as subjective or objective, but was also viewed in a holographic sense (M. Newman, telephone interview, 2000). According to Newman (1994), “Each moment has an explicate order and also enfolds all others, meaning that each moment of our lives contains all others of all time” (p. 62). Newman (1986) illustrated the centrality of space-time in the following example: Mrs. V. made repeated attempts to move away from her husband and to move into an educational program to become more independent. She felt she had no space for herself, and she tried to distance herself (space) from her husband. She felt she had no time for leisure (self), was overworked, and was constantly meeting other people’s needs. She was submissive to the demands and criticism of her husband (p. 56). Space, time, and movement later became linked with Newman’s (1986) assertion that the intersection of movement-space-time represented the person as a center of consciousness. Further, this varied from person to person, place to place, and time to time. Newman (1986) also emphasized that the crucial task of nursing is to be able to see the concepts of movement-space-time in relation to each other, and consider them all at once, recognizing patterns of evolving consciousness. In Health as Expanding Consciousness (Newman, 1986, 1994), Newman’s theory encompassed the work of Young’s spectrum of consciousness (Young, 1976). She saw Young’s central theme as being that self and universe were of the same nature. This essential nature could not be defined but was characterized by complete freedom and unrestricted choice at both the beginning and the end of life’s trajectory (Newman, 1986). Newman established a corollary between her model of health as expanding consciousness and Young’s conception of the evolution of human beings (Figure 23-2). She explained that individuals came into being from a state of consciousness, they were bound in time, found their identity in space, and through movement learned the “law” of the way that things worked; they then made choices that ultimately took them beyond space and time to a state of absolute consciousness (Newman, 1994). Newman (1994) also stated that restrictions in movement-space-time have the effect of forcing an awareness that extends beyond the physical self. When natural movement is altered, space and time are also altered. When movement is restricted (physical or social), it is necessary for an individual to move beyond self, thereby making movement an important choice point in the process of evolving human consciousness (Newman, 1994). She assumed that the awareness corresponded to the “inward, self-generated reformation that Young [spoke] of as the turning point of the process” (Newman, 1994, p. 46). When a person progresses to the state of timelessness, there is increasing freedom from time. Finally, the last stage is absolute consciousness, which Newman asserted is equated with love (Newman, 1994). With the realization that the early research testing of propositional statements stemmed from a mechanistic view of movement-space-time consciousness and failed to honor the basic assumptions of her theory, Newman shifted focus to authentic involvement of the nurse researcher as a participant with the client in the unfolding pattern of expanding consciousness (Newman, 2008). The unitary, transformative paradigm demanded that the research honor and reveal the mutuality of interaction between nurse and client, the uniqueness and wholeness of pattern in each client situation, and movement of the life process toward higher consciousness. Newman (2008) states, “The nature of nursing practice is the caring, pattern-recognizing relationship between nurse and client—a relationship that is a transforming presence” (p. 52). The protocol for this research was first started in 1994, and variations of this guide continue to be implemented in current praxis research. Litchfield (1999) explicated this process as “practice wisdom” in her work with families of hospitalized children, and Endo (1998) analyzed the phases of the process in her work with women with ovarian cancer. The data of this praxis research reveal evidence of expanding consciousness in the quality and connectedness of the client’s relationships and support the importance of the nurse’s creative presence in participants’ insight (M. Newman, personal correspondence, 2004, 2008). Variations of the praxis research have been utilized in numerous populations and settings (Newman, 2008; Picard & Jones, 2007). Newman used both inductive and deductive logic in early theory development. Inductive logic is based on observing particular instances and then relating those instances to form a whole. Newman’s theory development was derived from her earlier research on time perception and gait tempo. Time and movement, with space and consciousness, were subsequently used as central components in her early conceptual framework. These concepts helped explain “the phenomena of the life process and therefore of health” (Newman, 1979, p. 59). Newman (1997a) has described the evolution of the theory as it moved from linear explication and testing of concepts of time, space, and movement to an elaboration of interacting patterns as manifestations of expanding consciousness. Evolution of the theory of health as expanding consciousness as a process of evolving, in conjunction with the research, progressed through several stages (Newman, 1997a, 1997b). These stages included testing the relationships of the concepts of movement, space, and time, identifying sequential person-environmental patterns, and recognizing the centrality of nurse-client relationships or dialogue in the clients’ evolving insight and accompanying potential for action. The process actually became cyclical as the original concepts of movement-space-time emerged as dimensions in the unitary evolving process of consciousness (Newman, 1997a). Newman believes that research within the theory of health as expanding conscious is praxis, which she defines as a “mutual process between nurse and client with the intent to help” (Newman, 2008, p. 21). Further, this process focuses “on transformation from one point to another and incorporates the guidance of an a priori theory” (Newman, 2008, p. 21). Research and practice with the theory then are interwoven. In Newman’s view, the responsibility of professional nurses is to establish a primary relationship with the client for the purpose of identifying meaningful patterns and facilitating the client’s action potential and decision-making ability (Newman, 2008). Communication and collaboration with other nurses, associates, and healthcare professionals are essential (Newman, 1989). Nurses as primary care providers, focused directly and completely on relationships with clients, relate to her view of the role of professional nursing, which Newman (Newman, Lamb, & Michaels, 1991) referred to as nursing clinician-case manager, which is the sine qua non of the integrative model. Relating her theory of health as expanding consciousness and acknowledging the contemporary and radical shift in philosophy of nursing that views health as a unitary human field dynamic embedded in a larger unitary field, Newman (1979) believes that “the goal of nursing is not to make people well, or to prevent their getting sick, but to assist people to utilize the power that is within them as they evolve toward higher levels of consciousness” (p. 67). The task of nursing is not to try to change the pattern of another person, but to recognize it as information that depicts the whole and relate to it as it unfolds (Newman, 1994). From the Newman perspective, nursing is the study of “caring in the human health experience” (Newman et al., 1991, p. 3). The role of the nurse in this experience is to help clients recognize their own patterns, which results in the illumination of action possibilities that open the way for transformation to occur. At first, Newman’s theory of health was useful in the practice of nursing because it contained the concepts of movement and time that are used by the nursing profession and intrinsic to nursing interventions such as range of motion and ambulation (Newman, 1987a). Early research with the theory manipulated concepts of space, time, and movement. In addition to Newman, several researchers conducted research about time, space, or movement. Newman and Gaudiano (1984) focused on the occurrence of depression in the elderly and decreased subjective time. Mentzer and Schorr (1986) used Newman’s model of duration of time as an index to consciousness in a study of institutionalized elderly. Engle (1986) addressed the relationship between movement, time, and assessment of health. Schorr and Schroeder (1989) studied differences in consciousness with regard to time and movement, and in another study found that relationships among type A behavior, temporal orientation, and death anxiety as manifestations of consciousness had mixed results (Schorr & Schroeder, 1991). During the 1980s, Marchione, using health as expanding consciousness, investigated and reported the meaning of disabling events in families, presenting a case study in which an additional person became part of the nuclear family. The addition was a disruptive event for the family and created disturbances in time, space, movement, and consciousness, suggesting that Newman’s work with patterns could be used to understand family interactions (Marchione, 1986). Marchione (1986) and Pharris (2005) both advocate application of the theory to practice with communities. However, with evolution of the theory, the praxis research also incorporated practice, having a function of assisting clients in pattern recognition (Newman, 1990a). Schorr, Farnham, and Ervin (1991) investigated the health patterns in 60 aging women, using the theory as a framework. A study of music and pattern change in chronic pain by Schorr (1993) also supported Newman’s theory of health as expanding consciousness. Fryback’s (1991) dissertation revealed that persons with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection did, in fact, describe health within physical, health promotion, and spiritual domains and was consistent with Newman’s theory. The theory has been used in practice with various client populations. Kalb (1990) applied Newman’s theory of health in the clinical management of pregnant women hospitalized for complications of maternal-fetal health. Smith (1995) worked with the health of rural African American women. Yamashita (1995, 1999) studied Japanese and Canadian family caregivers, and Rosa (2006) worked with persons living with chronic skin wounds. Several studies have focused on patterns of persons with rheumatoid arthritis (Brauer, 2001; Neill, 2002; Schmidt, Brauer, & Peden-McAlpine, 2003). Research studies have focused on patterns of patients with cancer as a meaningful part of health (Barron, 2005; Bruce-Barrett, 1998; Endo, 1998; Endo, Nitta, et al., 2000; Gross, 1995; Karian, Jankowski, & Beal, 1998; Kiser-Larson, 2002; Moch, 1990; Newman, 1995c; Roux, Bush & Dingley, 2001; Utley, 1999). Other studies include life patterns of persons with coronary heart disease (Newman & Moch, 1991); patterns of persons with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Jonsdottir, 1998; Noveletsky-Rosenthal, 1996); life patterns of people with hepatitis C (Thomas, 2002); and patterns of expanding consciousness in persons with HIV and AIDS (Lamendola & Newman, 1994). Litchfield (1999) described the patterning of nurse-client relationships in families with frequent illness and hospitalization of toddlers, and its use in family health. Magan, Gibbon, and Mrozek (1990) reported on implementation of the theory, as one of several theories, in the care of the mentally ill. Weingourt (1998) reported on the use of Newman’s theory of health with elderly nursing home residents, and Capasso (2005) reported increased emotional and physical client healing as a result of use of the theory in nurse-client interactions. Additional research includes studies that involved recognizing health patterns in persons with multiple sclerosis (Gulick & Bugg, 1992; Neill, 2005) and spousal caregivers of partners with dementia (Brown & Alligood, 2004; Brown, Chen, Mitchell, & Province, 2007; Schmitt, 1991), as well as patterns in adolescent males incarcerated for murder (Pharris, 2002) and life experiences of Black Caribbean women (Peters-Lewis, 2006). Additional studies have included life patterns of women who successfully lose weight and maintain weight loss (Berry, 2002); victimizing sexuality and healing patterns (Smith, 1997); meaning of the death of an adult child to an elder (Weed, 2004); experience of family members living through the sudden death of a child (Picard, 2002); nurse facilitation of health as expanding consciousness in families of children with special health care needs (Falkenstern, 2003), and health as expanding consciousness to conceptualize adaptation in burn patients (Casper, 1999). Newman’s research as praxis has also been used to describe the lived experience of life passing in middle-adolescent females (Shanahan, 1993); patterns of expanding consciousness in women in midlife (Picard, 2000) and women transitioning through menopause (Musker, 2005); pattern recognition of high-risk pregnant women (Schroeder, 1993) and low-risk pregnant women (Batty, 1999); and patterns in families of medically fragile children (Tommet, 2003). It was the framework for analysis of patterns for evidence of empowerment in community healthcare workers by Walls (1999). Quinn (1992) reconceptualized therapeutic touch as shared consciousness. Lamb and Stempel (1994) described the role of the nurse as an insider-expert. Newman, Lamb, and Michaels (1991) described the role of the nurse case manager at St. Mary’s as emanating from a philosophical and theoretical base agreeing with the unitary-transformative paradigm and exemplifying an integrated stage of professional nursing. Further, the theory of health as expanding consciousness has been proposed as beneficial for the school nurse working with adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes (Schlotzhauer & Farnham, 1997). Gustafson (1990) found that practice as a parish nurse supported Newman’s theory of health as demonstration of pattern recognition. More recently, Endo and colleagues (2005) conducted action research involving practicing nurses and found that nurses experienced deeper meaning in their lives as a result of the transformative power of pattern recognition in their work with clients. Flanagan (2005) found that preoperative nurses working within the theory saw the effect of their presence in changing patient experiences. Additionally, Ruka (2005) developed a model of nursing home practice for use in pattern recognition with persons with dementia. Newman states that her research over time assisted not only clients who participated, but she and fellow researchers were also assisted, in gaining a better understanding of self as a nurse researcher and understanding the limitations of previous methods used. Newman (1994) further stated that research should center on investigations that are participatory and in which client-subjects are partners and co-researchers in the search for health patterns. This method of inquiry is called cooperative inquiry or interactive, integrative participation. Newman (1989, 1990a) has developed a method to describe patterns as unfolding and evolving over time. She used the method of interviewing a subject regarding different time frames to establish a pattern for that subject (Newman, 1987b). Newman (1990a) stated that during the development of a methodology to test the theory of health, “sharing our (researcher’s) perception of the person’s pattern with the person was meaningful to the participants and stimulated new insights regarding their lives” (p. 37). In 1994, she described a protocol for the research and labeled it hermeneutic dialectic. This method allows the pattern of person-environment to reveal itself without disturbing the unity of the pattern (M. Newman, personal correspondence, 2000). From the inception of Newman’s theory in the 1970s until the present, numerous nurse practitioners and scientists have used the theory to incorporate the concepts into their nursing practice or to elaborate the theory through research. Newman advocates a convergence of nursing theories as the basis of the discipline (Newman, 2003). She sees health as expanding consciousness as emerging from a Rogerian perspective, incorporating theories of caring, and projecting a transformative process (Newman, 2005). Newman (1986) stated that ideally, a new role is needed for the nurse to function in the paradigm of the evolving consciousness of the whole. “Nurses need to be free to relate to patients in an ongoing partnership that is not limited to a particular place or time” (Newman, 1986, p. 89). She suggested that nursing education should revolve around pattern as a concept, substance, process, and method. Education by this method would enable nursing to be an important resource for the continued development of health care. Newman (1986) stated that nursing is at the intersection of the focus of the healthcare industry; therefore, “nursing is in position to bring about the fluctuation within the system that will shift the system to a new higher order of functioning” (p. 90). Newman (2008) states, “attention to the nature of transformative learning will help to establish the priorities of the discipline” (p. 73). She sees a need for student-teacher personal transformation in nursing curricula. As students and teachers directly engage together in intuitive awareness, they will resonate with each other in a transforming way (Endo, Takaki, Abe, Terashima, & Nitta, 2007). However, as the paradigm shift has taken place in nurses’ views of their relationships with clients, many examples of application of the theory in traditional roles are evident (Newman, personal correspondence, 2008). Examining the pragmatic adequacy of Newman’s theory in relation to nursing education reveals that teaching the research method associated with the theory also teaches students a practice method that is congruent with the theory, and it is a means for students to experience transformation through pattern recognition (Newman, 2008). Newman sees the theory, the practice, and the research as a process rather than as separate domains of the nursing discipline. Teaching the theory of health as expanding consciousness necessitates a shift in thinking from a dichotomous view of health to a synthesized view that accepts disease as a manifestation of health. Not only that, learning to let go of the professional’s control and respecting the client’s choices are integral parts of practice within this framework. Students and practicing nurses who plan to use Newman’s theory will face personal transformation in learning to recognize patterns through nurse-client interactions. An individual’s personal experience will be the core not just of teaching and practice, but of research as well. Newman (1994) explained that the nurse would need to sense his or her own pattern of relating as an indication of the nurse-client interacting pattern. She emphasized that there needs to be a sense of the process of the relationship with clients from within, giving attention to the “we” in the nurse-client relationship (Newman, 1997b). Newman’s theory has been used in nursing education to provide some content into a model called the healing web. This model was designed to integrate nursing education and nursing service together with private and public education programs for baccalaureate and associate nursing degree programs in South Dakota (Bunkers, Bendtro, et al., 1992). Jacono and Jacono (1996) suggested that student creativity could be enhanced if nursing faculty applied the theory recognizing that all experience has the potential for expanding the creativity (consciousness) of individuals. Picard and Mariolis (2002, 2005) described the application of the health as expanding consciousness theory to teaching psychiatric nursing. Further, Endo and colleagues (2007) described a project in which faculty became involved with students in a project of pattern recognition, which resulted in transformation of student relationships.

Health as Expanding Consciousness

CREDENTIALS AND BACKGROUND OF THE THEORIST

RELATIONSHIP TO METAPARADIGM CONCEPTS

Nursing

Person

Environment

Health

THEORETICAL SOURCES

USE OF EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

MAJOR ASSUMPTIONS

THEORETICAL ASSERTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT

Early Designation of Concepts and Propositions

Synthesis of Patterns of Movement, Space-Time, and Consciousness

Emphasis on Experiential Process of Nurse-Client

LOGICAL FORM

ACCEPTANCE BY THE NURSING COMMUNITY

Research/Practice

Education

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access