Chapter 1. Health as a socio-ecological concept

Introduction

As health professionals our role spans across the health–illness continuum. The role of any community nurse, midwife, or other health professional ranges from preventing illness to protecting people from harm or worsening health once they have experienced illness, to recovery and rehabilitation. Community practice also involves a parallel role to protect communities from harm or stagnation, to help community citizens build capacity for future development, and to work in partnership with the population to restore their viability following any difficult times. Community health activities are therefore undertaken on many levels, for individuals, families, groups and entire communities.

Health is dynamic — constantly changing as our biology and genetic predispositions interact with the psychological, social, cultural, spiritual and physical environments that we live in.

They include educating communities and governments on the structures and supports conducive to good health, minimising risks to ill health or injury, and guidance to support recovery and sustainable health. The basis for this type of work is a combination of foundational knowledge, having the intellectual curiosity to seek out and, in some cases, generate research evidence for interventions, and social engagement with the community. Together these equip the nurse, midwife or other health practitioner with the skills for ongoing surveillance and monitoring, intervention and evaluation strategies, and political advocacy to lobby for family and community resources and supports.

Promoting the health of any community is therefore a multifaceted role. It is based on the holistic, socio-ecological perspective of health. Its philosophical foundation is entrenched in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of health, where it is not seen as one-half of a dichotomy of health and illness, but ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (WHO 1974:1). This definition of health also reflects the growing body of research evidence outlining the importance of the social determinants of health (SDOH). Researchers have found that the SDOH are even more influential on the health of the population than medical care, with studies showing the greatest health gains in the population over the past two centuries from changes in broad economic and social conditions (Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), 2008, Graham, 2004 and Link and Phelan, 2005). This chapter will examine the various SDOH, and some of the ways they influence the health of communities and the people who live in them. It will also address the important issue of health literacy. Health literacy is a major goal for practitioners working in community health.

The World Health Organization defines health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease’.

A well-informed, health literate population can participate fully in making health-related decisions that affect their personal health and the health of their community. The chapter culminates in a discussion of the research base for good and best practice in working effectively with communities.

Research is an important element in planning to improve and maintain the health of any community, particularly research into the SDOH. Although some community practitioners are new to researching the basis of their interventions, nurses, midwives and others have been systematically collecting and using research data for centuries. As early as the 19th century Florence Nightingale carefully documented various factors associated with outbreaks of illness in her community. Years later, scholars from psychology, sociology and other scientific disciplines, joined medical, nursing, and other health professions in seeking to explain and theorise about health (Syme 2005). As health scholars around the world expanded their research knowledge, their studies became circumscribed by what is now called the ‘McKeown thesis’. McKeown (1979) argued that medical care and technology were not responsible for improving health; the major improvements were due to social, environmental and economic changes, smaller family size, better nutrition, a healthier physical environment and a greater emphasis on preventive care. However, there is little evidence on how these factors interact to influence health in particular communities. Clearly, research evidence on the SDOH is needed to underpin community interventions. Throughout this and other chapters in this book, we provide examples of a wide range of research studies to guide these interventions. By committing ourselves to this scholarly approach to practice it is possible that over time, many of the compromises to community health may be overcome, and new, effective strategies developed for the benefit of society and communities everywhere.

We know that the major improvements in health over the past century are due to changes in social, environmental and economic conditions as well as smaller family size, better nutrition and a greater emphasis on preventive care. However, we need more research to demonstrate how these factors interact to influence health in communities.

At the end of this and other chapters, we provide an example of a research study into an issue relevant to community health. This is designed to provoke your thinking about the evidence base for practice, and how research can be used to optimise health. The case study for this chapter also introduces ‘The Millers’. We’ll ask you to complete a genogram of the family and ask that you consider their particular strengths and needs in the context of reflecting on the main issues covered in the chapter.

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 explain health, wellness, and community health as socio-ecological concepts

2 identify the social determinants and structures of health and wellness

3 examine the intergenerational factors that influence health

4 analyse the concept of social capital and its contribution to community health

5 examine the factors that influence community sustainability

6 explain the importance of health literacy in enhancing individual and community health capacity

7 investigate the role of research and evidence-based practice in promoting community health.

What is health?

As mentioned previously, health is a product of reciprocal interactions between individuals and their environments. Each of us brings to our environmental interactions a number of factors unique to us alone. These include the following:

• a personal history

• our biology as it has been established by heredity and moulded by early environments

• previous events that have affected our health, including past illnesses or injuries

• our nutritional status as it is currently, and its adequacy in early infancy

• stressors; both good and bad events in our lives that may have caused us to respond in various ways.

Clearly, health is multifaceted. Becoming and staying healthy ‘depends on our ability to understand and manage the interaction between human activities and the physical and biological environment’ (WHO 1992: 409).

Biological factors provide the foundation for an individual to develop as a relatively healthy person, which is an adaptive process. From birth, individuals are programmed to develop certain biologically preset behaviours (bio-behaviours) at critical and sensitive developmental periods. This ‘biological embedding’ influences how people interact with the genetic, social and economic contexts of their lives (Best et al 2003). However, the environments or conditions of a person’s life shape biological factors and the way individuals respond to the world around them (Hertzman, 2001 and Hertzman and Power, 2006). These include family and community characteristics, and aspects of the wider society that create opportunities or threats to health.

Although biological factors provide the foundation for an individual to develop into a healthy person, the environment or conditions of a person’s life shape these biological factors.

Social conditions are particularly important, because social environments provide the context for interactions in all other environments. When the social environment is supportive, creating a climate of trust and mutual respect a person is more likely to be empowered, in control of their life, and therefore their health. On the other hand, if their social situation is plagued by civil strife, an oppressive political regime, crime, poverty, unemployment, violence, discrimination, food insecurity, diseases or a lack of access to health and social support services they may be disempowered, leaving them less likely to become healthy or recover from illness when it occurs. These issues that arise from power imbalances and unfair societal structures create inequalities in health (Edwards and MacLean Davison, 2008 and Marmot, 2006). This is because people who are living in disadvantaged or disempowered situations are unable to access the same resources for health as those who live in more privileged situations.

When a social environment is supportive, a person will feel empowered. If a social environment is affected by such things as war, crime, unemployment or poor access to health services a person may feel disempowered.

Health and wellness

Healthy people’s lives are characterised by balance and potential. In a balanced state of health there is harmony between the physical, emotional, social and spiritual. When they are part of a healthy community there are opportunities for them to reach and maintain high levels of health or wellness. Wellness, as originally described by Dunn (1959) extends beyond health. In the community context, it reflects the dynamic relationship between people and their environment that arises when individuals use that environment to maintain balance and purposeful direction. This underlines the ecological nature of health and wellness. Contemporary definitions of health acknowledge the connectivity between people and the environment in two ways: first, health is dynamic rather than static, and second, the environment or context of people’s lives influences the extent to which they can reach their health potential. For example, people feel they have lifestyle choices, and if they choose, they will be able to exercise or relax in safe spaces. They have access to nutritious foods; students balance study with recreation; young families immunise their children and have time out from work to socialise, and older people have opportunities to stay active and socialise with others.

Wellness is achieved when there is harmony between the physical, emotional, social and spiritual health of the individual and their environment.

Eckersley et al (2005) explain that optimism, trust, self-respect and autonomy make us happy and therefore create feelings of wellbeing. The importance of happiness has been acknowledged by many health scholars, who are now expanding their research agenda to explore the relationship between happiness and health (Baum 2009). This type of research can be linked back to the proposal in the 1970s by the King of Bhutan that instead of focusing only on gross domestic product (GDP), nations should be concerned with the ultimate purpose in life, which is happiness. He proposed a gross national happiness (GNH) index comprised of psychological wellbeing, the use of time, community vitality, culture, health, education, environmental diversity, living standard and governance (online www.grossnationalhappiness.cm/gnhIndex/introductionGNH.aspx 2). Since then, many initiatives have been developed to try to bring this balanced perspective of health into mainstream thinking. The Happy Planet Index, developed in the United Kingdom refocused wellbeing on the criteria of average life expectancy, life satisfaction and ecological footprint (Marks et al 2006). The Canadian Index of Wellbeing has also adopted this approach, computing measures of quality of life into social, economic and environmental trends in Canadian cities (Hancock 2009). All of these measures address social health, and they are based on the knowledge that happiness and wellbeing increase longevity and make immune systems more robust, which in many cases, improves health (Layard 2005).

The pursuit of happiness from a social perspective lies in contrast to the consumerism in society today that fosters and exploits a restless, insatiable expectation that we need more and more. Although most of us enjoy having something to strive for, consumer goods offer hollow outcomes. Instead, we may find higher levels of wellness in communities that allow people to live in a stable, democratic society, to enjoy the company of family and friends, to have rewarding work that yields sufficient income, to feel personal happiness with the ability to address any mental health problems, to set goals related to common values, and to have some means of attaining guidance, purpose and meaning (Diener & Seligman 2004). This illustrates a clear link between personal and community wellness; in other words, a level of harmony between health and place.

Defining ‘community’ and ‘community health’

In the most basic terms, the word community simply means that which is common. We often think of a community as the physical or geographical place we share with others, or the place from which care is delivered (Crooks & Andrews 2009). However, an ecological view focuses on the community as an interdependent group of plants and animals inhabiting a common space. People depending on one another, interacting with each other and with aspects of their environment, distinguish a living community from a collection of inanimate objects. Communities are thus dynamic entities that pulsate with the actions and interactions of people, the spaces they inhabit and the resources they use. Healthy communities are the synthesis or product of people interacting with their environments. This is an evolutionary concept, in that community health is ‘a dynamic and evolving process’ (Baisch 2009:2467). It is created by people working collaboratively to shape and develop the community in a way that will help them achieve positive health outcomes. A ‘healthy community’ is one of those positive outcomes. Community health is defined as follows:

Community health is grounded in philosophical beliefs of social justice and empowerment. Dynamic and contextual, community health is achieved through participatory, community development processes based on ecological models that address broad determinants of health.

(Baisch 2009:2472)

An ecological definition of community focuses on a community as a group of people who are dependent on one another and who inhabit a common space.

Healthy communities have a number of common qualities as outlined in Box 1.1.

BOX 1.1

1 Clean and safe physical environment.

2 Peace, equity and social justice.

3 Adequate access to food, water, shelter, income, safety, work and recreation for all.

4 Adequate access to health care services.

5 Opportunities for learning and skill development.

6 Strong, mutually supportive relationships and networks.

7 Workplaces that are supportive of individual and family wellbeing.

8 Wide participation of residents in decision-making.

9 Strong local cultural and spiritual heritage.

10 Diverse and vital economy.

11 Protection of the natural environment.

12 Responsible use of resources to ensure long term sustainability.

(Online: http://www.ohcc-ccso.ca/en//what-makes-a-healthy-community)

Community health and wellness

Community wellness (or wellbeing) refers to an optimal quality of community life, one that meets people’s needs and that creates harmony and social justice within a vibrant, sustainable community (Rural Assist Information Network (RAIN) 2009 Community wellbeing, 2009 and The Ian Potter Foundation, 2009). The Government of Victoria (2009) identifies a number of priorities that promote community wellbeing. These include having governments that are responsive to the needs of new communities, building community capacity through a sense of belonging, working towards economic developments to sustain the population, and creating safe environments with opportunities for healthy activity, recreation and social interaction. These are essential characteristics of community health.

As members of a community, our lives are closely interwoven with the lives of others, some

The essential characteristics of community health include having governments that are responsive to the needs of communities, building capacity through a sense of belonging, providing for economic development to sustain the population, and creating safe environments that encourage healthy activity, recreation and social interaction.

We also hold membership in various population groups on the basis of gender, age, physical capacity or culture. In the context of all of these group memberships, we interact with a moveable feast of other richly diverse communities. To these interactions we bring our own individuality; the combination of genetic predispositions, history, knowledge, attitudes, preferences and perceptions of capacity. Each community, in turn, brings to each of its members a set of distinct environments: physical, psychological, social, spiritual and cultural. Our socio-ecological interactions shape a characteristic community character, which determines the extent to which community members will become a cohesive entity. Each of these interactions, whether with our families, social groups or our physical environment, transforms the community as well as its residents. Bandura (1977) called this reciprocal determinism. By reciprocal determinism he meant that both the behaviours of people and the characteristics of their environments are determined by the set of dynamic exchanges between them.

Ecological exchange can yield both constraints and enhancements to personal and community health. Some of the more familiar constraints on health and wellbeing arise from the effects of contaminants in the physical environment, such as air and water pollution, infectious diseases and/or injury. Some degree of risk to health and wellbeing is also present in the social environment; in the workplace, school and neighbourhood. Interactions with our environment in recreation, education and social interchange present opportunities for achieving higher levels of health and wellbeing. Interactions between community members and the health care system are also imbued with challenges and opportunities for illness prevention and health improvements. For those of us whose role involves helping people achieve and maintain good health and protection from illness or injury, it is important to understand the effects of these interactions.

Reciprocal determinism is simply the combination of what an individual brings to a community, what a community brings to the individual, and how these interact.

Like individuals, communities are open to a variety of interpretations. If you were to ask ‘How healthy is the community in which I live?’ a number of issues might come up. To gain at least a cursory view of the community you could look around at the geography. You might find yourself in a small town with plenty of vegetable gardens, well-kept houses, playgrounds and sporting fields, a community centre complete with child-minding facilities, a mix of healthy looking young and older people on the streets, none of whom are smoking, and public transportation. A very different picture may emerge if you cast your gaze to an inner-city neighbourhood where children play on the streets between parked cars, ramshackle buildings loom skyward with broken windows punctuating the places where people live, cars hoon around the corners, no older people walk the streets, and children seem to be tending to younger children with no adults supervising their activities. A vastly different community might emerge the further you get from the city. Depending on which continent you were in, you might find starving babies suffering from rampant disease, or Indigenous people smoking around a campfire, or an isolated farmer, too poor to either heat his frozen house or cool a sweltering one, reacting to his frustration by abusing his wife and children. Or, you might find happy, contented families, enjoying the fruits of their toils, whether on the land or in the city.

In each of the situations mentioned above, you could jump to a number of conclusions about the way the physical environment enhanced or impeded the health of the community. But in each community, a set of unseen influences lies just below the physical surface. For example, the small town may be comfortably situated in a place where everyone wanting employment has a job, because of a political decision taken some time previously to relocate a manufacturing company there. The playgrounds and sporting fields may be a product of a community development program and a workplace policy that provides flexible working hours so parents can take their children to sports. A local non-denominational church may have been built to double as a respite centre for carers, or a mothers group, or some other activity that keeps adults connected with one another. The schools may be well resourced because a government body has decreed that children should not be disadvantaged irrespective of where they live. In contrast, the inner-city neighbourhood may be neglected by government policies, with inadequate educational facilities. Young mothers raising children alone may be working swing shifts, leaving young children in the care of other children. Vandals may be receiving no deterrents because of a lack of funding for social policies, perhaps because military spending takes precedence over social services and local policing. In the rural area, a farming community may be suffering from the lack of markets for their produce, or have no chance of fertilising their lands to grow produce in the first place because of conservation policies. They may also be disadvantaged by natural disasters such as drought, or be vulnerable to mortgage lenders, substandard places to shelter, or unemployment. These aspects of community life are considered SDOH.

How healthy is the community you live in? What factors make it healthy? What factors make it less healthy?

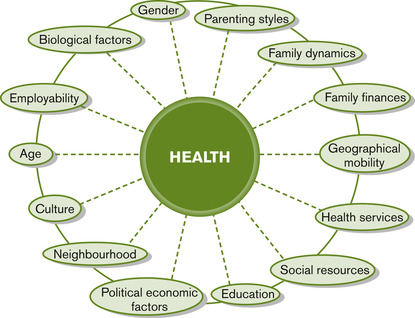

Social determinants of health

The SDOH consist of a number of overlapping factors that determine health and wellbeing. These include factors that begin at birth, such as biology and genetic characteristics, gender, culture and various family influences on healthy child development. Family influences include having socio-economic resources for parents to provide for their child, parenting knowledge and skills, a peaceful family life and adequate support systems. Social support networks that are inclusive across genders, cultures and educational opportunities are also social determinants.

The SDOH are a number of overlapping social and physical factors that contribute to health and wellbeing.

Support systems influence a person’s ability to cope with life’s stressors, and to make decisions about personal health practices that either prevent illness or maintain health. Other social determinants are a function of interactions between the individual, family and community, such as having a healthy and supportive neighbourhood, with adequate transportation and spaces for recreation, being able to access food and water, and services for health and child care when they’re needed, and having employment opportunities with good working conditions and sufficient income. Many of these determinants are embedded in the political and economic environment, where policy decisions affecting community life are made.

Within the SDOH are a number of structural conditions. For example, a community’s social development needs structures to create employment opportunities, and a physical environment that supports healthy lifestyles and personal health practices. People need access to clean air, water and nutritious foods at a reasonable cost. They also need to have reasonable working conditions so that they can achieve a work–life balance. Other structures in the social environment that support health and wellbeing include health and social support services such as hospitals, medical practitioners, nurses and other allied health professionals who are accessible where and when they are needed. Structural supports for health also include government services that provide income protection in the case of unemployment, infrastructure such as safe roads and public transportation, and schools, playgrounds and adult recreational facilities that offer the opportunity for holistic health and wellbeing. Socio-political structures include equitable systems of governance over the community and society, to ensure preservation of resources through wise economic choices and a commitment to conservation; fairness in allocating resources across all groups in the population, and systems that protect people from harm or disempowerment.

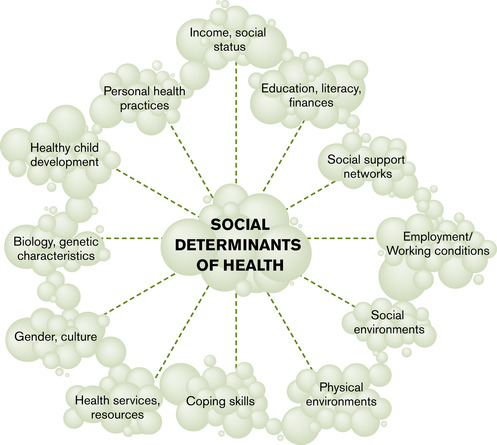

The diagram in Figure 1.2 illustrates the social and structural determinants of health from a socio-ecological perspective. The metaphor of a cascade of bubbles is used to show the dynamic interaction between factors (Wilcox 2007). Each bubble interfaces with many others, and if one bubble is displaced or happens to pop, there is a cascade effect, where the surface tension and connectivity of the others are changed. One bubble may be directly influenced by an adjacent bubble, but it is also indirectly influenced by that bubble’s connections to other surfaces. The bubbles may also merge and increase or decrease in size or in relation to one another. If there are changes in the wider environment, such as policy changes or a major environmental change, all bubbles may be affected or even disappear. In terms of the metaphor it would be like blowing air across the entire cascade or changing the water flow (Wilcox 2007).

|

| Figure 1.2 |

The ‘social determinants’ approach to health resonates with the notion of human rights and social justice. Social justice refers to the ‘fair distribution of society’s benefits, responsibilities and their consequences’ (Edwards & MacLean Davison 2008:130). This means that as health professionals, we have an obligation to identify unfairness or inequities, and their underlying determinants, advocating for human rights, and working towards just economic, social and political institutions (Edwards and MacLean Davison, 2008 and Whitehead, 2007).

Social justice occurs when the benefits, responsibilities and consequences of society are equally and fairly distributed between people.

Equitable, socially just conditions in our communities and society are a matter of life and death, affecting the way people live, their chances of becoming ill or their risk of premature death (CSDH 2008). In 2005, recognising the human rights implications of good health and the role of social determinants in supporting health and wellbeing, the WHO assembled an international Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). The Commission represents 19 countries, including Australia. After gathering information for 3 years, members met to consider global progress on eliminating disparities in health and how to encourage a more equitable social world.

The commissioners were united in three concerns: their passion for social justice, their respect for evidence and their frustration with a lack of progress on global responses to the SDOH (CSDH 2008). They recommended that governments everywhere take up the challenge of working with health and other organisations to improve health for the world’s citizens. This involves reframing health services in terms of primary health care (PHC), ensuring sufficient health professionals to provide care, addressing economic issues, overcoming inequitable, exploitative, unhealthy and dangerous working conditions, including restoration of work–life balance for families, and providing social protection for all people across the life course (CSDH 2008). These overarching goals urge us to act in concert with members of our communities, igniting our passion for health and social justice and combining it with research that will build better understanding of what works, where, for what populations, with what outcomes.

Governments worldwide are starting to recognise the importance of the SDOH in achieving health for all people.

The role of communities in intergenerational health

The quality of community health often changes dramatically over time to influence the way people grow and develop. For some, an ideal mix of conditions can create a positive start to life that becomes sustained into adulthood and throughout ageing. This is a ‘life course’ approach to understanding health. Improvements to the SDOH (housing, employment opportunities, transportation or social services) can provide optimal conditions in which all family members flourish and maintain good health over time. For others, a disadvantaged start to life may not be overcome by sufficient changes in any of the environments affecting their lives. So changing circumstances can create either threats or opportunities to health and wellbeing. For example, some physical environments have become transformed by global warming and droughts, creating natural disasters such as flooding, fires and other weather events, leaving entire families at risk of homelessness. For those already disadvantaged by poverty, discrimination or a lack of social support this can perpetuate ill health.

The family’s socio-economic status is an important determinant of health. Research studies have shown that there is a ‘social gradient’ in health, whereby those employed at successively higher levels have better health than those on lower levels (Navarro, 2009 and Hertzman and Power, 2006). This creates disadvantage from birth for some children. A child born into a lower socio-economic family for example, may be destined for an impoverished life, creating intergenerational ill health. This child lives in a situation of ‘double-jeopardy’, where interactions between the SDOH conspire against good health. Without external community supports the family may spiral into worsening circumstances, affecting their child’s opportunities for the future. This is the case for many Indigenous people, whose parents have not had access to adequate employment or community supports that would sustain their own health, much less that of their children. They become caught in a cycle of vulnerability where the SDOH interact in a way that creates disempowerment across generations. Political decisions governing employment opportunities may hamper the parents’ ability to improve finances.

A ‘social gradient’ exists in health. That is, those who are employed or earn income at successively higher levels have better health than those who are unemployed or have lower levels of income.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access