Chapter 8 HEALTH AND WELLNESS

CONCEPTS OF HEALTH AND WELLNESS

Health and wellbeing are integral elements of each person’s identity and, as such, influence actual and potential interactions with every aspect of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) promotes a positive concept of health, with defining characteristics that capture the many interrelated determinants of health as well as the importance of cultural and spiritual beliefs on health outcomes (WHO 1992). The WHO has actively supported a societal shift from focusing on illness to focusing on health, recognising that personal concepts of health are derived initially from family norms and values relating to health. For example, a child whose parents openly enjoy smoking cigarettes while denying any link with respiratory disease will share that belief until such a time that other events challenge those beliefs. Personal concepts of health are also shaped by geographical location, socioeconomic status and social structures, all of which influence and support family norms related to diet and lifestyle as well as health care access.

To complete this broad overview of health and illness it is important to recognise the interrelatedness of physical and mental wellbeing as well as the interplay of both internal and external factors on each individual’s state of health. Each system and subsystem within the human body continuously exchanges information to maintain a steady state or homeostasis in the face of actual or perceived change. When these adjustment processes fail to maintain an adequate physiological balance, disease or illness may result. Responses to both internal and external challenges to homeostasis vary according to the magnitude of the challenge and the emotional readiness of each individual to cope with change. Nutritional status, age, pre-existing disease and social support also influence individual responses; thus, different dimensions of wellbeing are infinitely related and linked in the socio-physical dimensions of health (see Clinical Interest Box 8.1).

MODELS OF HEALTH AND WELLNESS

A model is a symbolic representation of a complex issue such as health and provides a framework for understanding and guidance. Models are developed from research studies that identify constant factors pertaining to an issue, with recognition of links to other factors that shape or influence the outcome. Models of health can, for example, be used to predict health needs and outcomes in relation to health-related behaviours. They may also facilitate nurses’ understanding of clients’ care requirements in relation to their health beliefs and practices.

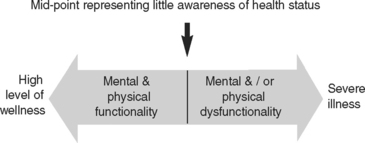

The health–illness continuum model of health assists nurses to recognise individuals’ states of health and wellness as a position on a continuum that ranges from a high level of wellness at one end to severe illness at the other (Figure 8.1).

The health belief model (Crisp & Taylor 2005) demonstrates the link between people’s beliefs about health and their health-related behaviours or health practices. Health beliefs can be defined as the concepts or ideas about health that the individual believes as true. Health practices can be defined as the activities or behaviours that the individual will engage in as a result of, or in line with, their beliefs about health. Many health practices can become unconscious habits, such as cleaning teeth before going to bed, and for most people health beliefs are grounded in family health beliefs, values and practices. Family health beliefs usually reflect the dominant societal attitudes to health at that time.

Further information or experiences may either support these beliefs or contribute to a change. This model identifies two factors that influence change in health-related behaviours: personal readiness for change, and the strength of the stimulus. Readiness for change may be related to an event such as health breakdown or a close encounter with death, or it may arise from dissatisfaction with personal states of health. The strength of the stimulus for change is directly related to the individual’s perception of personal vulnerability to death or disease and it is precisely at this time that health education is most effective in the short term. This model may be best understood through the scenario in Clinical Interest Box 8.2.