Chapter 10. Health and gender

healthy women, healthy men

Introduction

Environmental conditions play a large part in gender relations, in determining the physical and social geographies of people’s lives, and the effect of ‘place’ on their lives, especially their access to material resources and support. Rurality, for example, operates as a determinant of inequity, affecting men and women in different ways, limiting opportunities for women outside the home and causing considerable health risks for men. Rural communities, such as the one pictured (French Pass, Marlborough Sounds, New Zealand), may be several hours by road, boat or plane from health care.

|

Urban life also creates different outcomes for men and women, most notably in their relative access to sufficient income, appropriate housing and employment. In any environment, parenting is enacted in different roles for women and men, and, combined with socio-economic status, tends to leave women in a more inequitable position than their male counterparts, both within and beyond marriage. At the extreme, poverty affects men and women differentially, with more profound effects for women who are caring for children. This creates a ‘feminisation of poverty’, as we mentioned in Chapter 5. Women are typically those with the fewest resources, and have the least involvement in the type of health and social decision-making that would help them improve their current situation and their potential for the future. We discuss this in relation to their roles as partners and mothers.

The community is an ideal place to address inequities that arise from social exclusion, particularly in the process of unravelling constraints and facilitating factors involved in developing capacity. Gender equity and differential access to childhood education, health literacy, prevention, care and economic opportunities are pivotal to community

Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

1 explain the importance of social inclusion and social exclusion

2 describe the social determinants of health, illness, injury and disability according to gender relations

3 identify the societal factors that impinge on the health of women and men, and how these could be modified to achieve greater equity in health for both

4 explain the central issues that have to be considered to achieve equitable health outcomes for men and women

5 identify the health literacy needs of men and women, respectively

6 develop a community strategy for improving the health of women and the health of men using the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion.

Inequality, social exclusion and gender

In previous chapters we have addressed the link between socio-economic disadvantage and poor health. Social exclusion plays an important role in this relationship. Socially excluded people are unable to access opportunities to become educated, earn a living, receive social support for their personal needs, live in safe houses and neighbourhoods with a secure food supply and a viable physical environment, raise their children in a non-violent home, cultivate friendships, or participate in social and political life.

Gender, race and ethnicity are important social determinants of health. Social exclusion on the basis of any of these can be detrimental to health.

Social exclusion affects men, women and children in a wide variety of ways. For example, children living in a jobless household grow up with the risk of becoming socially excluded through a lack of education and other opportunities to change the course of their lives (Commonwealth of Australia 2008a). Women confined to physical work from an early age, such as occurs in many developing countries, are socially excluded by virtue of having no opportunities to become educated or to change their status. Men working in isolated circumstances may be socially excluded because they have few opportunities to find a partner, raise a family or gain employment in a geographic area with social amenities. Members of sexually diverse minority groups such as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT) are also at risk of social exclusion, especially young gay men who live in environments where there are strict norms of socially determined heterosexual behaviour. Racial minorities are often socially excluded from some of the most significant aspects of the dominant culture, with profound negative impacts on their health and wellbeing. People with disabilities can also be excluded from social participation on the basis of a perceived lack of capabilities. Although social exclusion can arise from a lack of capabilities, it is often the result of a denial of resources, rights, goods and services that are available to the majority of people in society. It affects the quality of life of individuals and equity and cohesion in the community and society (Levitas et al 2007).

Cultural norms can play a major role in social exclusion, particularly in ascribing roles on the basis of gender. In some cultures women’s domination by men is responsible for major traumatic events throughout their life course, and sometimes, systematic violence against them. Family violence and sexual abuse contribute to social exclusion, in some cases, pushing young people into self-exile, and, for those who were vulnerable before the violence or abuse occurred, worsening their experience of being marginalised (Commonwealth of Australia 2008a). Men can also be disadvantaged by cultural norms. Rural stoicism and resignation to the hardships of being a family breadwinner is deeply embedded in rural culture, to the extent of being a health risk. The intersection of gender and culture can, in these cases, create health risks that are embedded in societal structures, especially power structures and processes (Kickbusch 2008). Because gender relations are part of social structures, processes, and the interactions people have in their everyday lives, gender is dynamic. This means that a person’s gender is not simply a static attribute, or simple assignment of a sex role. Instead, gender is defined in the way it is socially constructed in the context of personal experiences (Emslie & Hunt 2008).

The division of household labour is one of the most contentious gender issues facing families in today’s society.

Life experiences have gendered expectations. For example, the experience and expectations of being a parent differ for men and for women, and these change over time (Vespa 2009). An individual may undergo role transitions to partner, to parent, to divorced person, with each of these transitions shaping the way gender is viewed. For example, researchers have found that the longer single women work, the less they believe they should stay home after becoming a parent (Vespa 2009). This is a reflection of the changes in social life that have evolved with the prevalence of the dual-earner family. Social norms still continue to dictate gender roles, creating pressure on women to nurture, and pressure on men to be breadwinners, with varying outcomes (Loscocco & Spitzke 2007). But as we outlined in Chapter 8, the work–family system is out of synchrony with the way people actually live their lives. Women are changing faster, and men are changing slower, making the division of household labour the most contentious gender issue (Loscocco & Spitzke 2007). A man’s work continues to be the way he accomplishes ‘gender’, and the accompanying power structure that affords him greater prestige and money than women (Loscocco & Spitzke 2007).

Employers shape understandings of gender by providing greater opportunities to men in the workplace, because of their role as a family provider (Vespa 2009). Yet at the same time that women are moving into new roles as family providers, they continue to be expected to undertake the traditional homemaker role (Loscocco & Spitzke 2007). Within the family, expectations are both gendered and racialised, which can affect the way women or men are treated, and how they come to view their role in society (Vespa 2009). In many places, particularly developing countries, women bring home 90% of their wages for household expenses, while men contribute 30–40% (World Bank 2009). Single-parent households headed by women continue to have a high risk of impoverishment (United Nations Family Planning Association [UNFPA] 2000). If societies were truly inclusive, there would be no discrimination on the basis of gender, race or ethnicity. Instead, members of all groups would be equally empowered to live the life to which they aspire (Sen 1999).

Empowerment

Empowerment is a term frequently found in the literature on gender and discrimination, but often with ambiguous meanings. In many cases, empowerment is explained as advocacy, the type of actions nurses and others take to help people overcome disempowerment (Kasturirangan 2009). For example, in helping women victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), empowerment may be equated with safe shelter, counselling and other support services. As admirable as these measures are, the term empowerment actually refers to the processes by which people gain mastery over their lives. It may be experienced as a perceived sense of control, or an actual increase in control over resources (Rappaport 1987). Empowerment often begins with critical awareness, or participating in activities to create social and political change. Some of those actions may be aimed at fostering ‘distributive justice’; that is, the equitable distribution of resources (Kasturirangan 2009).

Empowerment is when a person perceives they have control over their own life and resources. It is often confused with advocacy, which involves actions a nurse may take to help a person overcome disempowerment.

The extent of empowerment that is possible depends on the situation, and the needs and values of a person who is working towards empowerment. For example, some people can be empowered by information and the development of health literacy. Others would be frustrated by such an approach, given a lack of resources or opportunities to make changes in their lives, even if they had the knowledge to do so. Powerlessness is therefore highly contextualised to a person’s life. Ideally, empowerment begins with consciousness raising, understanding the oppressive social forces that are barriers to development, taking intentional action to overcome those forces, and sustaining a belief in the possibility for change (Love, in Kasturirangan 2009).

Disempowerment, especially disempowerment on the basis of gender, lies at the core of social exclusion. This is why the power imbalance between men and women is so important. In Western societies, men typically hold economic, political, organisational and physical power over women, and this affects many aspects of their lives. These societal-level power imbalances create multiple layers of disadvantage for women who may have begun life in vulnerable circumstances through poverty, racism or other forms of marginalisation, or whose pathway to adult life may be stymied by discrimination, and other gender-related barriers to development. In some cases, men can be disempowered relative to women; for example, through the biological power of childbirth. Recent research in New Zealand suggests that most fathers attending antenatal classes prior to childbirth found the courses irrelevant to their needs as fathers (Luketina et al 2009). However, given the right circumstances and support, the quality of parenting may be equal for both a father and a mother. The main issue for nurses and midwives practising in the community is that there are modifiable factors in community life that can change historical gender roles, to promote equity and equality of opportunity. To this end, the following discussion focuses on the experience of being a woman or a man in contemporary society, and how these experiences can shape health and wellbeing.

Women’s health issues

Women’s health issues are influenced by many factors: childbirth, gender-linked health conditions including unique reproductive health risks, women’s health behaviours, and their social disadvantage and longevity relative to that of men. Women’s innate constitution gives them an advantage over men in terms of life expectancy, but the social realities of being a woman can compromise the quality of her life (Emslie & Hunt 2008). Childbirth is the most recognisable biological event for women. Childbirth risks are a serious concern for women in developing countries, but they are relatively low in Australia and New Zealand. However, there has been an annual maternal death rate of 10–15 Australian women, and up to 10 women in New Zealand over the past 15 years, with several other deaths per year indirectly related to having given birth (Commonwealth of Australia, 2009 and New Zealand Health Information Service (NZHIS), 2007).

Globally, the two leading mortality risks for women are similar to those of men: cardiovascular disease and stroke. The gender difference lies in the fact that women’s symptoms may be different from those of men’s and they tend to develop later in life (World Health Organization [WHO] 2009). Because of the age difference in diagnosis, and a greater likelihood of co-morbidities, women have poorer outcomes from cardiovascular disease (Reibis et al 2009). Many die of sudden cardiac death before arrival to hospital, compared to men (Shaw et al 2009). It is interesting that women are also less likely to be treated according to guideline-indicated therapies, such as cardiac rehabilitation programs, despite evidence indicating the advantages of such programs (Lavie and Milani, 2009 and Shaw et al., 2009). When women are referred to rehabilitation programs, it is often for shorter periods of time than their male counterparts (Lavie & Milani 2009; WHO 2006). This under-treatment of women’s cardiovascular health has been linked to physicians’ lack of awareness of risk factors in women, and options for their treatment (Oertelt-Prigione & Regitz-Zagrosek 2009).

Globally, the two leading causes of death among women are cardiovascular disease and stroke.

The cumulative effects of different lifestyles and health risks from childhood to ageing also affect women and men differently. Poverty is a major problem for women worldwide. The persistence of poverty among women of wealthy nations seems a social contradiction, given the international declarations to alleviate inequality and discrimination during the 1990s. These included the 1993 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), ratified by 150 nations, excluding the United States and Afghanistan; the International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo (1994); and the Platform for Action of the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995) (Lewis 2005). Yet, discrimination against women and the lack of opportunities for them to develop their capacity is rampant around the world. Poor women are sometimes seen as responsible for their circumstances. Being a poor and dependent woman, particularly where there are children to support, attracts a societal judgement that somehow, a woman has a choice, and has chosen badly (Reid 2004). This kind of thinking helps justify the social exclusion of poor women, which becomes part of an endless cycle of deprivation. A woman may be too poor to access the means to manage her life and that of her children, to gain education, opportunities and resources. Inequity is then transformed into a deprivation of basic capabilities (Sen 1999). The gendered nature of the problem has been known for many years, yet the socio-economic disadvantage of many women in many countries, including the wealthy countries of the West, is not improving, and women remain disempowered around the world (WHO 2005).

A lack of education is another risk to women’s health. In every region of the world, educating girls is the single most powerful way to promote equitable personal opportunities, and pathways to health and wellbeing. It is also good for the economy, with a flow-on effect for building social cohesion. Women with access to education tend to marry later than uneducated women. They have smaller families, make better use of antenatal and delivery care, and understand how to use family planning methods. They seek medical care sooner in the event of illness, maintain higher nutritional standards, and raise their daughters to receive sufficient education to keep the cycle of health improvements moving in a positive direction (UNESCO, 2006 and United Nations Family Planning Association (UNFPA), 2000). Educated women typically have the level of health literacy to retain control over their reproductive function. They understand the issues involved, the presence of risk, and the steps that need to be taken to ensure health and safety for them and their babies. It is also widely accepted that education prepares mothers in developing early, enhanced child-rearing practices. Most educated mothers have an appreciation of the need to foster learning readiness and a good preschool foundation for subsequent stages of a child’s development (Karoly et al 2005).

Educating girls is the single most powerful way to promote equitable personal opportunities and pathways to health and wellbeing in any country of the world.

Other risks for women are linked to conditions that affect their health disproportionately, compared with men. As we reported in Chapter 6, boys have nearly twice as many injuries as girls, while girls have higher rates of asthma in their teenage years than boys (Commonwealth of Australia 2008a). By adulthood nearly twice as many women have asthma than their male counterparts (Valerio et al 2009). The development of asthma is also linked to overweight or obesity, creating a health risk that has been attributed to hormonal and metabolic factors. This correlation is related to increased oestrogen levels that are associated with the effect of obesity on the smooth muscles of the airway, and on inflammatory and immune system function (McCallister & Mastronarde 2008). The combination of these factors can impinge on women’squality of life, and cause low self-esteem. Cervical cancer is another unique risk for women, but screening has seen dramatic drops in mortality from this type of cancer (Commonwealth of Australia 2009). Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women, and, because of earlier diagnosis and treatment, deaths from breast cancer have been decreasing since the 1990s (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2009a and Ministry of Health New Zealand (MOHNZ), 2009). Lung cancer continues to be the leading cause of death for women. Lung cancer deaths and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have declined in men over the past few decades, primarily because men who began to smoke tobacco early in the last century have died. However, with women living longer, more die from lung cancer (AIHW 2008).

Another impact of women living longer than men is that they endure more years of illness and severe disability, especially for those with chronic conditions (AIHW 2009b). They also live alone for more of their lives, spending nearly twice as many hours alone per week than men (78% as compared with 37% for men) (AIHW 2009b). Women’s higher rate of dementia is also linked to their longevity, and they are more likely than men to be in aged care facilities. On the other hand, men are more likely to be hospitalised for mental illness (AIHW 2008). When women are diagnosed with mental illness such as depression, they tend to be quickly prescribed biochemical solutions, primarily antidepressants, without further investigations. Many remain on this type of medication for years, creating the impression that women’s mental health problems do not warrant in-depth discussion or longer-term exploration.

The longevity of women contributes to them enduring more years of illness, disability and living alone than men.

Protracted use of medications for women’s depression can be a mind-numbing solution to a problem that may have a social cause, such as workplace stress. Prolonged workload stress in women can be caused by multiple roles as partner, parent and worker (Kostiainen et al 2009). It can arise from a combination of overwork, a lack of opportunities in the workplace, being the family caregiver, or raising children as the head of a single-parent household (AIHW 2009b). Although paid employment is known to promote psychosocial health and wellbeing, a stressful and demanding job, combined with motherhood and a relationship, can lead to increased strain, psychological distress and burnout caused by exhaustion, depersonalisation and diminished personal accomplishment (Kostiainen et al 2009; ten Brummelhuis et al 2008). Managing the permeable boundaries between these roles, and their combined workload can also prevent women from accessing opportunities for physical activity, or other stress management supports (Coulter et al 2009).

Another area of vulnerability is the heightened risk of poor health outcomes for migrant women. Studies have shown that migrant women can be disadvantaged if their health is not considered as important as that of men, because of culturally determined subservient roles, or when cultural norms emphasise a fatalistic attitude towards illness rather than preventative care (Gholizadeh et al 2008). Some migrant women also have personal misperceptions of risk, especially coronary heart disease, and tend to ignore symptoms, rather than seek help. These misperceptions can also be accompanied by poor lifestyle habits in relation to diet and exercise. In Middle Eastern cultures, for example, the dominant cultural expectation of modesty means that women must dress according to cultural norms and exercise in gender-specific locations. This can act as a deterrent to exercise. Combined with these risks, is the added difficulty for women who are from non-English speaking backgrounds (NESB) trying to cope with employment, or other contexts where communication is important (Syed & Murray 2009). Workplace stress may be added to the stress of migration and the need to adapt to a different culture (Gholizadeh et al 2008). Some migrants also deal with the added stress of racism, placing their health and them in a situation of ‘double jeopardy’ (Syed & Murray 2009:415). Unless they have the time and opportunity to deal with stress, or neighbourhood supports, they may suffer severe health risks. For those dealing with mental health issues or severe stress, being precluded from exercising adds a layer of difficulty to their situation, particularly in light of the therapeutic value of exercise in preventing, or dealing with, stress and depression.

Refugee and migrant women have multiple health needs that may not be easily addressed due to cultural mores and poor health literacy skills.

Refugee women have some of the most acute health and social needs of any group in our communities. In Chapter 5, we mentioned the social justice implications of holding refugees in detention centres, and the compromises this causes to health. For women, the experience of many months in detention can cause lifelong mental health trauma, which cannot help but affect their children. In Australia, mandatory detention is enshrined in the Migration Act (Newman et al 2008). The experience is akin to immersing families in a prison culture, where infants and children have no opportunities for education or play, and their mothers’ role revolves around protecting them from witnessing the ‘mental deterioration, despondency, suicidality, anger and frustration’ experienced by their parents and others around them (Newman et al 2008:116). In detention, women and children are exposed to multiple suicide attempts, self-harm and other manifestations of a collective depression syndrome. This causes major psychosocial traumas, which often include multiple losses, post-traumatic stress syndrome, re-traumatisation through detention, severe depression, and the threat of repatriation to a country that was intolerable enough for them to risk their lives leaving (McLoughlin and Warin, 2008 and Newman et al., 2008). As nurses, our obligation to these imperilled women includes political advocacy to restore the fundamental human right to seek asylum, as is the case in New Zealand, where refugee policies are more closely aligned with the UN Charter of Human Rights (see Chapter 5).

Women and social disadvantage

In all societies, women are disadvantaged by their social position. Their sexual norms of behaviour are dictated by clinicians and sexologists on the basis of cultural expectations rather than the way women themselves interpret sexual needs (Hinchliff et al 2009). This is implicit in the pervasive and dominant heterosexual discourse of male ‘need’ and female ‘response’ (Hinchliff et al 2009). As we mentioned above, social exclusion also results from being deliberately excluded from education, which occurs in many parts of the world. In the global labour market, including Western nations, women occupy less prestigious and highly paid positions than men. This makes the workplace the setting where gender inequalities have been described as ‘both manifested and sustained, with consequent impacts on health’ (WHO 2006:v). Gender inequities can be found in many aspects of women’s work. Even though women in Western nations are not as oppressed as their sisters in developing countries, the decline of union power over the past few decades has left many women without solidarity

Despite growing levels of education, women still occupy the most poorly paid and least prestigious positions in the workforce, and are still engaged in more unpaid domestic work than men.

More women than men are engaged in unpaid domestic work, of low status and with no protective legislation and with only fragmented leisure time (WHO 2006; World Bank 2009). Those who enter non-traditional occupations suffer discrimination and sexual harassment more often than men, and earn less money. Women migrants are at the mercy of employers, who, in Australia,do not see cultural diversity as an important priority (Syed & Murray 2009). They are often exposed to hazards that are more harmful to them than to men, because safety standards have been

An important nursing study of how Middle Eastern women migrants in Sydney perceive their health risks found that there is a need for culturally and linguistically competent screening and health literacy programs for migrant women to overcome misperceptions about health and the causative factors for heart disease (Gholizadeh et al 2008). The researchers suggested a health promotion approach that would encourage help-seeking behaviours for mental disorders among immigrants, and support for culturally accepted alternative therapies, as well as strategies for managing stress (Gholizadeh et al 2008). Another Sydney study focused on social and health-related factors that affect women’s health when they live in disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Griffiths et al 2009). A nurse-led capacity building initiative provided women in this study with enhanced opportunities for social participation. It was particularly important, given that the neighbourhood where the study was situated has a large proportion of culturally and linguistically disadvantaged NESB women. The researchers found that by providing activities designed to promote friendship, social relations, support networks and social cohesion, the women developed a greater connectedness with their community, and had more positive views of their health and safety (Griffiths et al 2009). Both studies suggest that the community is an ideal context for promoting empowerment and social inclusion. Gathering systematic research evidence to identify women’s needs and perceptions is a significant step in the evolving nursing and midwifery research agenda in relation to women’s health.

Homelessness is a major problem for both men and women, but more so for women. The social context of homelessness leaves many women enmeshed in a network of alcohol and substance abusers (Wenzel et al 2009b). Violence and sexual abuse are frequently perpetrated against homeless women, especially those who are lesbian and/or bisexual, who are over-represented among the homeless (Wenzel et al 2009a). Women, especially young women, are vulnerable to sexual coercion, which can create long-term poor psychological, physical and sexual health (de Visser et al., 2007 and Fineran and Gruber, 2009). Sexual coercion can establish a cycle of health-compromising behaviours to cope with distress, such as drug or alcohol abuse, cigarette smoking, or other self-destructive behaviours, which often lead to further sexual abuse and disempowerment (de Visser et al 2007). In some cases, women who have fallen into this type of cycle, become further victimised by health and social services, especially where personnel have been ill-prepared to understand the depth or breadth of their distress (Adams Tufts et al., 2009, de Visser et al., 2007 and Postmus et al., 2009). A further difficulty can be the threat of having children removed from a violent home, which acts as a deterrent to disclosure (Postmus et al., 2009 and Terrance et al., 2008).

Intimate partner violence and empowerment

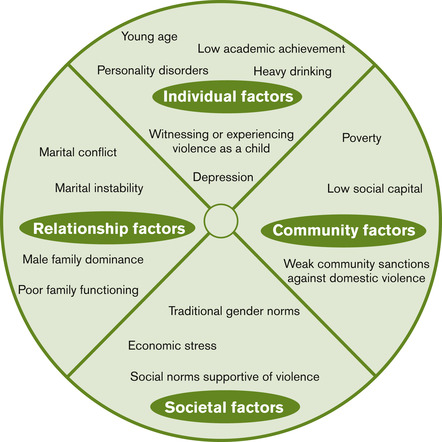

Although we have addressed intimate partner violence (IPV) in the context of family relations in Chapter 5, it is addressed here as one of the most gender-specific causes of women’s disempowerment. Gender-based violence is an act, or the threat of an act, intended to hurt or make women suffer physically, sexually or psychologically (Krantz & Garcia-Moreno 2005). Marriage is often used to legitimise a range of sexual and familial violent acts against women, and this varies with different cultures. These acts of violence include practices such as sex-selective abortion, denial of the means to prevent pregnancy or infection, female genital mutilation, treating young girls as a commodity-in-trade by marrying them off before puberty, or offering a girl’s sister to the matrimonial home as compensation for her death; providing a girl to a family to ensure an inheritance or fulfil an obligation to produce an heir; acid thrown to disfigure a woman because of dowry disputes; honour killing based on the presumption of infidelity; elder abuse; or various forms of trafficking in women and prostitution (WHO 2002). A large body of research indicates that children living in homes where woman abuse occurs are more likely to be abused themselves, to have behaviour problems, and be at increased exposure to other adversities such as alcohol and drug abuse, crime and other antisocial coping strategies (Holt et al 2008). The risk factors for violence against women vary across cultures, and to date, there remains no definitive pattern for predicting which factors will lead a man to abuse a woman. Those factors that have been identified comprise a multifaceted web of causation, where violence is a result of the interaction between aspects of the individual, the relationship, the community and society, as illustrated in Figure 10.1.

The frequency of violence against women has inspired a WHO global prevention campaign to heighten awareness of what has become a major source of injury among women (WHO 2008). Nurses and midwives throughout the world who work in communities are often best positioned to respond to this. Many already are leading advocates for championing the rights of women and addressing IPV, and its effects on health and wellbeing. The research agenda informing their practice is gradually expanding, creating greater awareness of such issues as the link between IPV and women’s failure to access cervical screening (Loxton et al 2009). The move towards screening for violence in health settings is also gaining momentum, particularly with research studies indicating that women appreciate being asked about abuse (Adams Tufts et al., 2009, Feder et al., 2006 and Hathaway et al., 2008). Nurse researchers in New Zealand interviewed women who had attended either an emergency department or PHC setting to canvass their views of having been screened for violence, and found that 97% were pleased to have been asked about the issue (Koziol-McLain et al 2008). The women reported that being screened afforded them an opportunity to learn about IPV, and the resources available to them. They also saw the screening encounter as giving them permission to talk about abuse in their lives (Koziol-McLain et al 2008).

Screening for interpersonal violence is an effective means of reaching women who may be at risk of violence. It also offers the opportunity to provide support and safety as needed.

The New Zealand and other screening protocols are based on empowerment and safety, and ensuring that there are adequately prepared health professionals to be of primary, secondary and tertiary assistance to women. Researchers have found that the services that do have a lasting impact on women’s ability to survive abuse such as intimate partner violence (IPV), rape or child abuse, are those that provide for women’s immediate needs through welfare benefits, food and spiritual counselling (Postmus et al 2009). Helping women gain financial independence has also been identified as the strongest predictor of a woman being able to leave the violent partner (Kim & Gray 2008). Economic and social support has been found to be more helpful in the long run, than the punishment law-and-order approach currently used in many places, which often creates more danger for women (Morgaine, 2009 and Paterson, 2009). Financial support and practical services can help women become self-sufficient, and begin to develop self-efficacy and empower them to live their lives in freedom. Once their immediate needs are met, longer-term empowerment can be based on providing them with the opportunity to explore the issues of power and control embedded in their relationships (Boonzaier, 2008 and Whitaker et al., 2007). Support groups, advocacy, shelter, education, legal aid and collaboration between service providers are also important components of service provision (Hathaway et al., 2008, Paterson, 2009 and Postmus et al., 2009). Equally as important is the need for mutual support friendship networks, which women often find the most accessible means of support.

Violence against an intimate partner is usually part of a gendered relationship of power and control; typically men attempting to control women. Sometimes gender-related violence is perpetrated on individuals on the basis of their gender expression as an LGBT person. In male to female violence, the male tyrant abuses his power because of an inability to control a female partner. But this may be an oversimplification of a complex set of relations, often defying disentanglement. In some societies where women have low status, men can control their wives through economic dependence, without reverting to violence. In other, more equitable societies where women have well-established economic power and a role in decision-making, violence is also less prevalent. Violence is highest in societies where there is greater economic equality, but where sex role stereotypes prevent women from being decision-makers. Campbell’s (2001) research around the world shows that the greatest danger lies in situations where women’s status is changing, and in contention with men’s status, challenging their control. This often occurs in situations where, after many years of domestic life, a woman chooses to develop her educational and economic capacity by undertaking formal studies, or secures a job that may be beyond her partner’s expectations of her.

Another situation that places a woman at risk is family separation. With so many marriages in Australia and New Zealand ending in divorce a large number of households are in upheaval, because of the change to the couple’s power relations. Violence in these families, often subjects young children to the conflicts related to family separation. In many cases, they are witness to, or unwitting pawns in episodes of IPV, leading up to family separation, during protracted negotiations, and following the separation. This cycle also repeats itself in many blended families. In the case of culturally sanctioned violence, women and children may also be involved in systematic, patriarchal terrorism in their own homes for a wide range of reasons, usually violating norms of obedience to the perpetrator. For adults, the gender wars of everyday life are difficult. For children, they often have lasting effects. Some child victims of violence grow up to find love and commitment elusive, and often replicate their dysfunctional upbringing with their own children. The cradle of violence in their family lives therefore becomes a cradle of societal violence (Strauss 2001).

In the LGBT community, violence is often perpetrated for no other reason than a person’s intolerance of diversity, the inability to control others’ sexual identity or expression. Gay relationships have the added difficulty of few available sources of support or assistance. Like women victimised by their partners, the gay victim needs to find a way out of the situation where their life is under the control of someone else. Also like women in an IPV situation, the gay victim may be caught up in a situation from which they can see no way out. Many victims of IPV tend to direct their efforts to reducing the violence, instead of leaving. This is particularly the case for women with children who have no economic resources, and no alternative avenue of assistance. In many violent partnerships, the woman’s life becomes dominated by trying to please the abuser/controller. The abuser tries to exploit the relationship, creating further dependency through little acts of treachery; creating a financial debt, or holding her to ransom by excessive neediness or a sense that she is the abusive one. During this time, the situation becomes dysfunctional for both of them, and for the children.

Young children witnessing IPV develop no sense of a woman’s experience of self-esteem. They see their mother as a whipping post, and they feel her frustration and defeat. How then can a child of such a household partner develop effective relationships of equal power, characterised by respect, support and a sense of the future? Does this occur because society labels domestic violence a woman’s problem, instead of a problem of civilisation itself? If this is society’s approach, we pay only lip service to social justice, and the world continues to privilege one gender over another, and prevent alternative forms of gender expression. As nurses and midwives gender-based violence is a human rights issue. Our obligation, like that of other members of society, is to engage in policy debates and let our voices reverberate in the chambers of those who do not appreciate that all people are deserving of a non-violent, harmonious and optimistic future.

Men’s health issues

Like women’s health, men’s health is created in the SDOH, but this is not always recognised. Society is often gender-blind, especially when it comes to the socially determined differences between men and women. It is far easier for most people to relate to men’s health, and women’s health, in terms of biological factors, categorising health and health needs in terms of their respective reproductive systems or body parts, instead of socially constructed patterns of behaviours. Images of health and wellbeing are also engineered by the media. These images disguise reality, by portraying biologically perfect specimens doing exciting things or, in complete contrast, images of young people engaged in a wide range of antisocial acts. Little wonder that those on the verge of developing their gender identity are uncertain of where to find role models. Some of the most important gender issues for men are bound up in stereotypical roles ascribed by society. Some men acknowledge their androgynous selves (having both male and female characteristics) without a problem, but others experience role strain in dealing with the fact that they have multidimensional, and sometimes complex, character traits.

Will Courtenay (2000), who is one of the leading men’s health researchers, argues that social and institutional structures help to sustain and reproduce men’s health risks and the social construction of men as the stronger sex. These structures reproduce a hegemonic view of gender. Hegemony refers to the fact that men are more culturally valued in Western society, and therefore the dominant sex. Gender, as an SDOH, is one of the most significant influences on health-related behaviour for men, as well as for women, yet common perceptions of gender as a social determinant revolve around women’s health. The way men negotiate gender roles actually creates higher health risks in comparison to women. The cluster of healthy lifestyle behaviours that men have come to see as synonymous with masculinity are deadly: smoking, drinking and driving, unhealthy diets, avoiding exercise or screening for various conditions. Health is equated with strength and control, illness is not masculine (Nobis & Sanden 2008).

Men’s unhealthy behaviours are due to a combination of social and cultural expectations regarding what is considered to be the ‘male ideal’.

Men’s lifestyles and health

Men’s lifestyles are also determined by the social gradient, where they sit in relation to socio-economic status, as determined by factors such as education and employment. Men at the lower end of the gradient especially, tend to see their bodies as a work instrument, and large body size as an indication of strength and dominance (Khlat et al 2009). Large body size can also be culturally mediated. Tongan men, for example, consistently choose larger body sizes as more attractive in both men and women (Coyne in MOHNZ 2008a). Another lifestyle factor impeding exercise lies in men’s employment. For many men, strenuous manual work limits their motivation for recreational exercise. Although men at higher levels of the social gradient are more disposed towards physical exercise for recreation, this group also tends to value being physically dominant. This differs from women, who, at higher levels see slimness as a marker of beauty and professionalism, as distinct from those at the lower end of the social gradient, who associate being overweight with femininity, and maternal qualities (Khlat et al 2009). Another distinction between men’s and women’s ‘embodiment’ is that in Western society, women’s bodies are extensively defined and overexposed, whereas societal forces take men’s bodies for granted and exempt them from the same type of scrutiny (Coward in Courtenay 2000).

To some extent men’s unhealthy behaviours are due to the greater social pressure to conform, relative to women. Conforming to the male ideal means a man sees himself as not only strong, but independent, self-reliant, robust and tough (Courtenay 2000). In the process, men deny weakness, or vulnerability, assume emotional and physical control, and the appearance of strength. This construction of masculinity has been explained in terms of mastery of self and others (Brown 2009). Men respond to societal expectations by dismissing any need for help, displaying aggressive behaviour and physical dominance, and a ceaseless interest in sex (Courtenay 2000). Although some behaviours are shaped by ethnicity, social class and sexuality, most men also take risks to assert their masculine side. They brag about resisting the need for sick leave from work, boast that drinking does not impair their driving, and dismiss the need for preventative health care, all aimed at maintaining their ranking among other men (Courtenay 2000).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree