H

Head and neck cancer

Description

Most head and neck cancers arise from squamous cells that line the mucosal surfaces of the head and neck. Most people present with locally advanced disease. Disability from the disease and treatment is great because of the potential loss of voice, disfigurement, and social consequences.

Clinical manifestations

Early signs of head and neck cancer vary with tumor location. Cancer of the oral cavity may be initially seen as a red or white patch in the mouth, an ulcer that does not heal, or a change in the fit of dentures.

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

The stage of the disease is determined based on tumor size (T), number and location of involved nodes (N), and extent of metastasis (M). TNM classifies disease as stage I to stage IV (see p. 777).

■ Advanced lesions of the larynx are treated by a total laryngectomy in which the entire larynx and preepiglottic region are removed and a permanent tracheostomy is performed (see Tracheostomy, p. 732). Radical neck dissection frequently accompanies total laryngectomy. Depending on the extent of involvement, extensive dissection and reconstruction may be performed.

Nutritional therapy

After radical neck surgery, the patient may be unable to take in nutrients through the normal route of ingestion. Parenteral fluids are given for the first 24 to 48 hours.

When the patient can swallow, give small amounts of thickened liquids or pureed foods with the patient in high Fowler’s position. Close observation for choking is essential. Suctioning may be necessary to prevent aspiration.

Nursing management

Goals

The patient with head or neck cancer will have a patent airway, no complications related to therapy, adequate nutritional intake, minimal to no pain, the ability to communicate, and an acceptable body image.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

Include information about risk factors in health teaching. Encourage good oral hygiene. Teach patients about safe sex practices to prevent HPV infection. If cancer has been diagnosed, tobacco and alcohol cessation is still important as the likelihood of a cure is diminished if these behaviors continue.

For procedures that involve a laryngectomy, teaching should include information about expected changes in speech. Establish a means of communication for the immediate postoperative period.

After surgery, maintenance of a patent airway is essential and a laryngectomy (tracheostomy) tube will be in place. Keep the patient in semi-Fowler’s position to decrease edema and tension on the suture lines. Monitor vital signs frequently because of the risk of hemorrhage and respiratory compromise. Immediately after surgery the postlaryngectomy patient requires frequent suctioning via the tracheostomy tube.

Patient and caregiver teaching

Patient and caregiver teaching

■ Instruct the patient and caregiver on how to manage tubes and whom to call if there are problems.

Head injury

Description

Head injury includes any trauma to the scalp, skull, or brain. A serious form of head injury is traumatic brain injury (TBI). In the United States in hospital emergency departments, an estimated 1.7 million people are treated and released with TBI.

Deaths from head trauma occur at three time points after injury: immediately after injury, within 2 hours of injury, and approximately 3 weeks after injury.

Types of head injuries

Scalp laceration

Because the scalp contains many blood vessels with poor constrictive abilities, even relatively small wounds can bleed profusely. The major complications of scalp lesions are blood loss and infection.

Skull fracture

Fractures frequently occur with head trauma. Fractures may be closed or open, depending on the presence of a scalp laceration or extension of the fracture into the air sinuses or dura.

Major potential complications of skull fracture are intracranial infections and hematoma, as well as meningeal and brain tissue damage.

Head trauma

Brain injuries are categorized as diffuse (generalized) or focal (localized). In diffuse injury (i.e., concussion, diffuse axonal), damage to the brain cannot be localized to one particular area of the brain, whereas a focal injury (e.g., contusion, hematoma) can be localized to a specific area of the brain.

Diffuse injury

Concussion is a minor, sudden, transient, and diffuse head injury associated with a disruption in neural activity and a change in the level of consciousness (LOC). The patient may not lose total consciousness. Signs include a brief disruption in LOC, amnesia for the event (retrograde amnesia), and headache. Manifestations are generally of short duration.

Although concussion is generally considered benign and usually resolves spontaneously, the symptoms may be the beginning of a more serious, progressive problem. At the time of discharge it is important to give the patient and caregiver instructions for observation and accurate reporting of symptoms or changes in neurologic status.

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is widespread axonal damage occurring after a mild, moderate, or severe TBI.

Focal injury

Focal injury can be minor to severe and can be localized to an area of injury. Focal injury consists of lacerations, contusions, hematomas, and cranial nerve injuries.

Lacerations involve actual tearing of brain tissue and often occur with compound fractures and penetrating injuries. Tissue damage is severe, and surgical repair of the laceration is impossible because of the nature of brain tissue. If bleeding is deep into the brain parenchyma, focal and generalized signs develop. Prognosis is generally poor for the patient with a large intracerebral hemorrhage.

A contusion is the bruising of brain tissue within a focal area. It is usually associated with a closed head injury. A contusion may contain areas of hemorrhage, infarction, necrosis, and edema and frequently occurs at a fracture site.

Complications

Epidural hematoma

An epidural hematoma results from bleeding between the dura and inner surface of the skull. An epidural hematoma is a neurologic emergency and is usually associated with a linear fracture crossing a major artery in the dura, causing a tear. It can have a venous or an arterial origin.

■ Venous epidural hematomas are associated with a tear of the dural venous sinus and develop slowly.

Manifestations typically include an initial period of unconsciousness at the scene, with a brief lucid interval followed by a decrease in LOC. Other symptoms may be headache, nausea and vomiting, or focal findings. Rapid surgical intervention to evacuate the hematoma and prevent cerebral herniation, along with medical management for increasing ICP, can dramatically improve outcomes.

Subdural hematoma

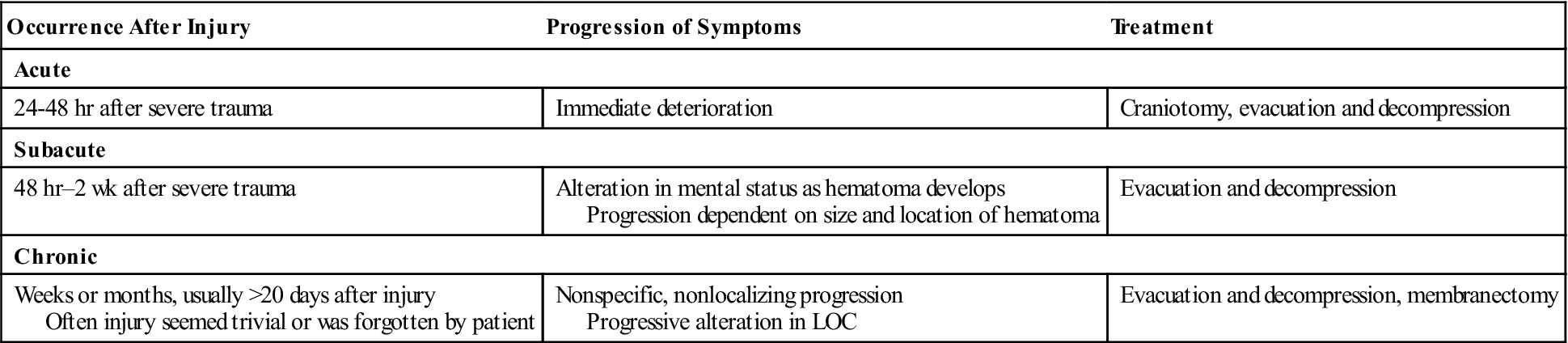

A subdural hematoma occurs from bleeding between the dura mater and the arachnoid layer of the meninges. The hematoma usually results from injury to the brain tissue and its blood vessels. A subdural hematoma is usually venous in origin, with a slow development of the hematoma, but rapid development can occur if the hematoma is of arterial origin. Subdural hematomas may be acute, subacute, or chronic (Table 40).

Table 40

| Occurrence After Injury | Progression of Symptoms | Treatment |

| Acute | ||

| 24-48 hr after severe trauma | Immediate deterioration | Craniotomy, evacuation and decompression |

| Subacute | ||

| 48 hr–2 wk after severe trauma | Alteration in mental status as hematoma develops Progression dependent on size and location of hematoma | Evacuation and decompression |

| Chronic | ||

| Weeks or months, usually >20 days after injury Often injury seemed trivial or was forgotten by patient | Nonspecific, nonlocalizing progression Progressive alteration in LOC | Evacuation and decompression, membranectomy |

Intracerebral hematoma

An intracerebral hematoma occurs from bleeding within the brain tissue. It usually occurs within the frontal and temporal lobes, possibly from the rupture of intracerebral vessels at the time of injury.

Diagnostic studies

Collaborative care

Emergency management of the patient with head injury includes measures to prevent secondary injury by treating cerebral edema and managing increased ICP (see Table 57-9, Lewis et al, Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1372). The principal treatment of head injuries is timely diagnosis and surgery if necessary. For the patient with a concussion or contusion, observation and management of increased ICP are primary management strategies.

Nursing management

Goals

The patient with an acute head injury will maintain adequate cerebral oxygenation and perfusion; remain normothermic; achieve control of pain and discomfort; be free from infection; have adequate nutrition; and attain maximal cognitive, motor, and sensory function.

Nursing diagnoses/collaborative problems

Nursing interventions

One of the best ways to prevent head injuries is to prevent car and motorcycle crashes.

Acute intervention.

The general goal of nursing management of the head-injured patient is to maintain cerebral oxygenation and perfusion and prevent secondary cerebral ischemia. Surveillance or monitoring for changes in neurologic status is critically important because the patient’s condition may deteriorate rapidly, necessitating emergency surgery.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is useful in assessing the LOC (see Glasgow Coma Scale, p. 766). Indications of a deteriorating neurologic state, such as a decreasing LOC or lessening of motor strength, should be reported to the health care provider, and the patient’s condition should be closely monitored.

The major focus of nursing care for the brain-injured patient relates to increased ICP (seeIncreased Intracranial Pressure: Nursing Management, p. 346).

■ Diplopia can be relieved by use of an eye patch.

■ Nausea and vomiting may be a problem and can be alleviated by antiemetic drugs.

■ Headache can usually be controlled with acetaminophen or small doses of codeine.

If the patient’s condition deteriorates, intracranial surgery may be necessary. A burr-hole opening or craniotomy may be indicated, depending on the underlying injury. The patient is often unconscious before surgery, making it necessary for a family member to sign the consent form for surgery. This is a difficult and frightening time for the patient’s caregiver and family and requires sensitive nursing management. The suddenness of the situation makes it especially difficult for the family to cope.

Rehabilitation.

Once the condition has stabilized, the patient is usually transferred for acute rehabilitation management. There may be chronic problems related to motor and sensory deficits, communication, memory, and intellectual functioning.

Progressive recovery may continue for 6 months or more before a plateau is reached and a prognosis for recovery can be made. Nursing management depends on specific residual deficits. In all cases the family must be given special consideration. They need to understand what is happening and be taught appropriate interaction patterns.

Headache

Description

Headache is probably the most common type of pain experienced by humans. The majority of people have functional headaches, such as migraine or tension type, whereas others have organic headaches caused by intracranial or extracranial disease.

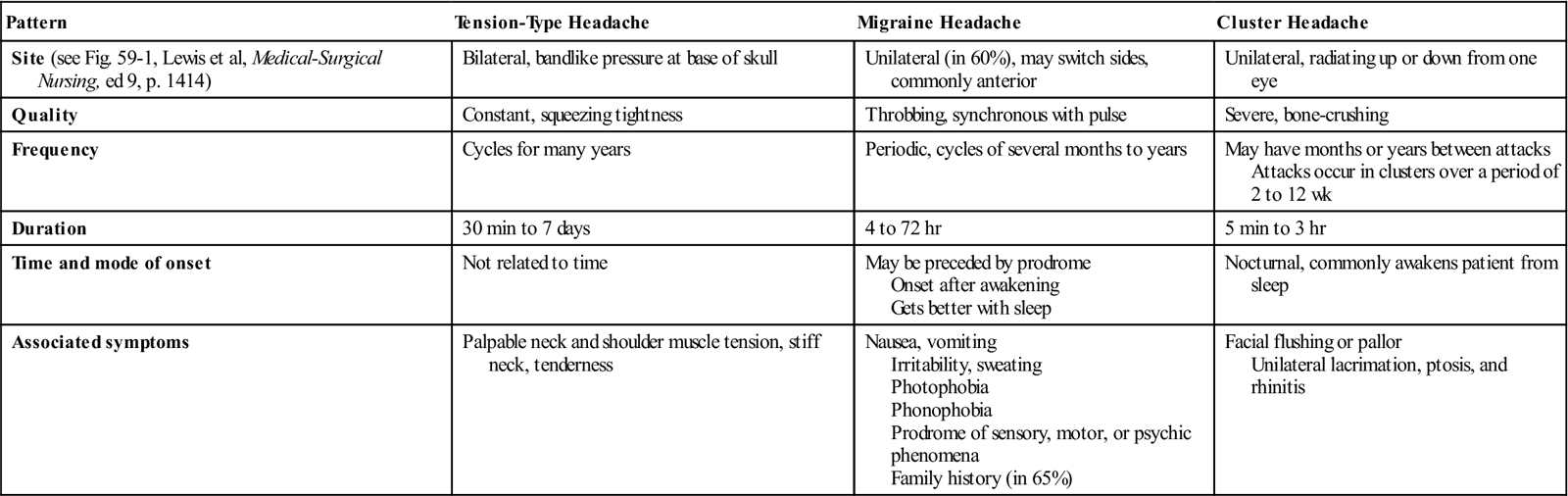

■ Primary headaches are those not caused by a disease or another medical condition. They include tension-type, migraine, and cluster headaches. Characteristics of primary headaches are shown in Table 41.

Table 41

Comparison of Types of Headaches

| Pattern | Tension-Type Headache | Migraine Headache | Cluster Headache |

| Site (see Fig. 59-1, Lewis et al, Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed 9, p. 1414) | Bilateral, bandlike pressure at base of skull | Unilateral (in 60%), may switch sides, commonly anterior | Unilateral, radiating up or down from one eye |

| Quality | Constant, squeezing tightness | Throbbing, synchronous with pulse | Severe, bone-crushing |

| Frequency | Cycles for many years | Periodic, cycles of several months to years | May have months or years between attacks Attacks occur in clusters over a period of 2 to 12 wk |

| Duration | 30 min to 7 days | 4 to 72 hr | 5 min to 3 hr |

| Time and mode of onset | Not related to time | May be preceded by prodrome Onset after awakening Gets better with sleep | Nocturnal, commonly awakens patient from sleep |

| Associated symptoms | Palpable neck and shoulder muscle tension, stiff neck, tenderness | Nausea, vomiting Irritability, sweating Photophobia Phonophobia Prodrome of sensory, motor, or psychic phenomena Family history (in 65%) | Facial flushing or pallor Unilateral lacrimation, ptosis, and rhinitis |

Tension-type headache

Tension-type headache, also called stress headache, is the most common type of headache and is characterized by its bilateral location and pressing/tightening quality. It is usually of mild or moderate intensity and can last from minutes to days. It is likely that neurovascular factors similar to those involved in migraine headaches play a role in the development of tension-type headaches.

Clinical manifestations.

Patients usually present with a bilateral frontal-occipital headache described as a constant, dull pressure, or bandlike headache associated with neck pain and increased tone in the cervical and neck muscles. There is no prodrome (early manifestation of impending disease) in tension-type headache. The headache does not involve nausea or vomiting, but may involve sensitivity to light (photophobia) or sound (phonophobia).

Diagnostic studies.

Careful history taking is the most important diagnostic tool. Electromyography (EMG) may reveal sustained contraction of the neck, scalp, or facial muscles. If tension-type headache is present during physical examination, increased resistance to passive movement of the head and tenderness of head and neck may be present.

Migraine headache

Migraine headache is a recurring headache characterized by unilateral or bilateral throbbing pain, a triggering event or factor, and manifestations associated with neurologic and autonomic nervous system dysfunction. The most common age for migraine onset is between ages 20 and 30 years, with women being affected more than men. Risk factors for migraine include family history, low level of education, low socioeconomic status, high workload, and frequent tension-type headaches.

Pathophysiology.

The current theory is that a complex series of neurovascular events initiates a migraine headache. People who have migraines have a state of neuronal hyperexcitability in the cerebral cortex, especially in the occipital cortex. Approximately 70% of those with migraine have a first-degree relative who also had migraine headaches.

Migraines can be preceded by prodrome and aura. The prodrome may precede the headache by several hours or several days.

In many cases, migraine headaches have no known precipitating events. However, for other patients, the headache may be precipitated or triggered by foods, hormonal fluctuation, head trauma, physical exertion, fatigue, stress, and drugs.

Clinical manifestations.

Migraine without aura is the most common type of migraine headache. Migraine with aura occurs in only 10% of migraine headache episodes.

The headache may last 4 to 72 hours. During the headache phase, some patients may tend to “hibernate”; that is, they seek shelter from noise, light, odors, people, and problems. The headache is described as a steady, throbbing pain that is synchronous with the pulse. Although the headache is usually unilateral, it may switch to the opposite side in another episode. In some patients, the symptoms of the migraine headaches may become progressively worse over time.

Diagnostic studies.

There are no specific laboratory or radiologic tests for migraine headache. The diagnosis is usually made from the history. Neurologic and other diagnostic examinations are often normal.

Cluster headache

Cluster headache, a rare form of headache, involves repeated headaches that typically last 2 weeks to 3 months, and then the patient goes into remission for months to years. The clusters occur with regularity, usually occurring at the same time each day, during the same seasons of the year.

Pathophysiology.

Neither the cause nor pathophysiology of cluster headache is fully known. The trigeminal nerve has a role in the production of pain, but cluster headaches also involve dysfunction of intracranial blood vessels, the sympathetic nervous system, and pain modulation systems. Imaging studies show hypothalamic activation at the onset of cluster headache. Alcohol is the only dietary trigger. Strong odors, weather changes, and napping are other triggers.

Clinical manifestations.

The cluster headache is one of the most severe forms of headache, with intense pain lasting from a few minutes to 3 hours.

Diagnostic studies.

Diagnosis is primarily based on the history. Asking patients to keep a headache diary can be useful. CT scan, MRI, or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may rule out an aneurysm, a tumor, or an infection. A lumbar puncture may rule out other disorders.

Collaborative care

If no systemic underlying disease is found, the type of headache guides the therapy. Table 59-3, Lewis et al, Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, p. 1417 summarizes current therapies for prophylaxis and symptomatic relief of headaches. These therapies include drugs, meditation, yoga, biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation training.

Drug therapy

Tension-type headache.

Drug treatment usually involves aspirin, acetaminophen, or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) used alone or in combination with a sedative, muscle relaxant, or tranquilizer. However, many of these drugs have serious side effects.

Migraine headache.

Drug treatment is aimed at terminating or decreasing the symptoms of the acute attack. Many people with mild or moderate migraine can obtain relief with NSAIDs, aspirin, or caffeine-containing combination analgesics. For moderate to severe headaches, the triptans have become the first line of therapy.

Cluster headache.

Because these headaches occur suddenly, often at night, and are not long lasting, drug therapy is not as useful as it is for other types of headache. Prophylactic medications may include verapamil (Isoptin), lithium, ergotamine, melatonin, or divalproex (Depakote).

Nursing management

Goals

The patient with a headache will have reduced or no pain, experience increased comfort and decreased anxiety, demonstrate understanding of triggering events and treatment strategies, use positive coping strategies to deal with pain, and experience increased quality of life and decreased disability.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

Headaches may result from an inability to cope with daily stresses. An effective therapy may be to help patients examine their lifestyle, recognize stressful situations, and learn to cope with them more appropriately. Help the patient identify precipitating factors and develop ways to avoid them. Encourage daily exercise, relaxation periods, and socializing because each can help decrease the recurrence of headache.

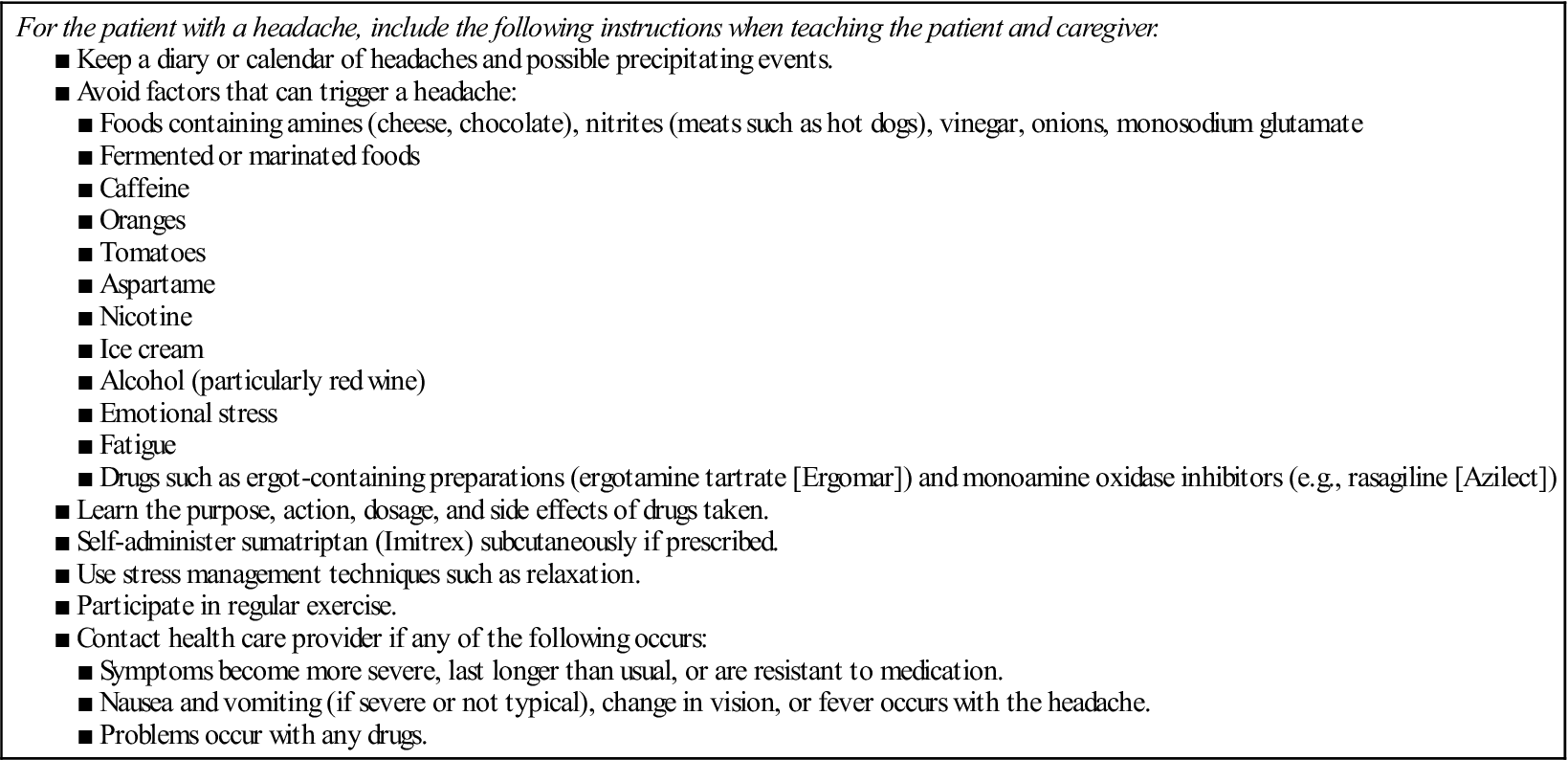

Patient and caregiver teaching

Patient and caregiver teaching

A teaching guide for the patient with a headache is provided in Table 42.

Table 42

Patient and Caregiver Teaching Guide

Headaches

Heart failure

Description

Heart failure (HF) is an abnormal clinical syndrome involving impaired cardiac pumping and/or filling of the heart. This results in the inability of the heart to provide sufficient blood to meet the oxygen needs of the tissues. In clinical practice, the terms acute and chronic HF have replaced the term congestive HF (CHF) because not all HF involves pulmonary congestion.

HF is associated with numerous types of cardiovascular diseases, particularly long-standing hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), and MI.

Pathophysiology

HF may be caused by any interference with the normal mechanisms regulating cardiac output (CO). CO depends on (1) preload, (2) afterload, (3) myocardial contractility, and (4) heart rate (HR). Any changes in these factors can lead to decreased ventricular function and subsequent HF.

Heart failure is classified as systolic or diastolic failure. Systolic failure results from an inability of the heart to pump effectively. It is caused by impaired contractile function (e.g., MI), increased afterload (e.g., hypertension), cardiomyopathy, and mechanical abnormalities (e.g., valvular heart disease). The hallmark of systolic dysfunction is a decrease in the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF).

Diastolic failure is the inability of the ventricles to relax and fill during diastole. Decreased filling results in decreased stroke volume and CO and venous engorgement in both the pulmonary and systemic vascular systems. The diagnosis of diastolic failure is based on the presence of HF symptoms with a normal EF. Diastolic failure is usually the result of left ventricular hypertrophy from chronic hypertension, aortic stenosis, or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Mixed systolic and diastolic failure is seen in disease states such as dilated cardiomyopathy, in which poor systolic function (weakened muscle function) is further compromised by dilated left ventricular walls that are unable to relax.

The patient with ventricular failure of any type has low systemic arterial BP, low CO, and poor renal perfusion. Whether a patient arrives at this point acutely (from an MI) or chronically (from worsening cardiomyopathy or hypertension), the body’s response to this low CO is to mobilize compensatory mechanisms to maintain CO and BP. The main compensatory mechanisms include (1) sympathetic nervous system activation, (2) neurohormonal responses, (3) ventricular dilation, and (4) ventricular hypertrophy.

HF is usually manifested by biventricular failure, although one ventricle may precede the other in dysfunction.

■ Right-sided failure causes a backup of blood into the right atrium and venous circulation. Venous congestion in the systemic circulation results in peripheral edema, hepatomegaly, and jugular venous distention. The primary cause of right-sided failure is left-sided failure. Cor pulmonale (right ventricular dilation and hypertrophy caused by pulmonary pathologic conditions) can also cause right-sided failure (see Cor Pulmonale, p. 159).

The primary cause of right-sided HF is left-sided HF. In this situation, left-sided HF results in pulmonary congestion and increased pressure in the blood vessels of the lung (pulmonary hypertension). Eventually, chronic pulmonary hypertension (increased right ventricular afterload) results in right-sided hypertrophy and HF.

Manifestations

Acute decompensated heart failure

In acute decompensated HF (ADHF), an increase in the pulmonary venous pressure is caused by failure of the left ventricle (LV). This results in engorgement of the pulmonary vascular system. This early stage is clinically associated with a mild increase in the respiratory rate and a decrease in partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2).

ADHF can manifest as pulmonary edema. This is an acute, life-threatening situation in which the lung alveoli become filled with serosanguineous fluid. The most common cause of pulmonary edema is acute LV failure secondary to CAD.

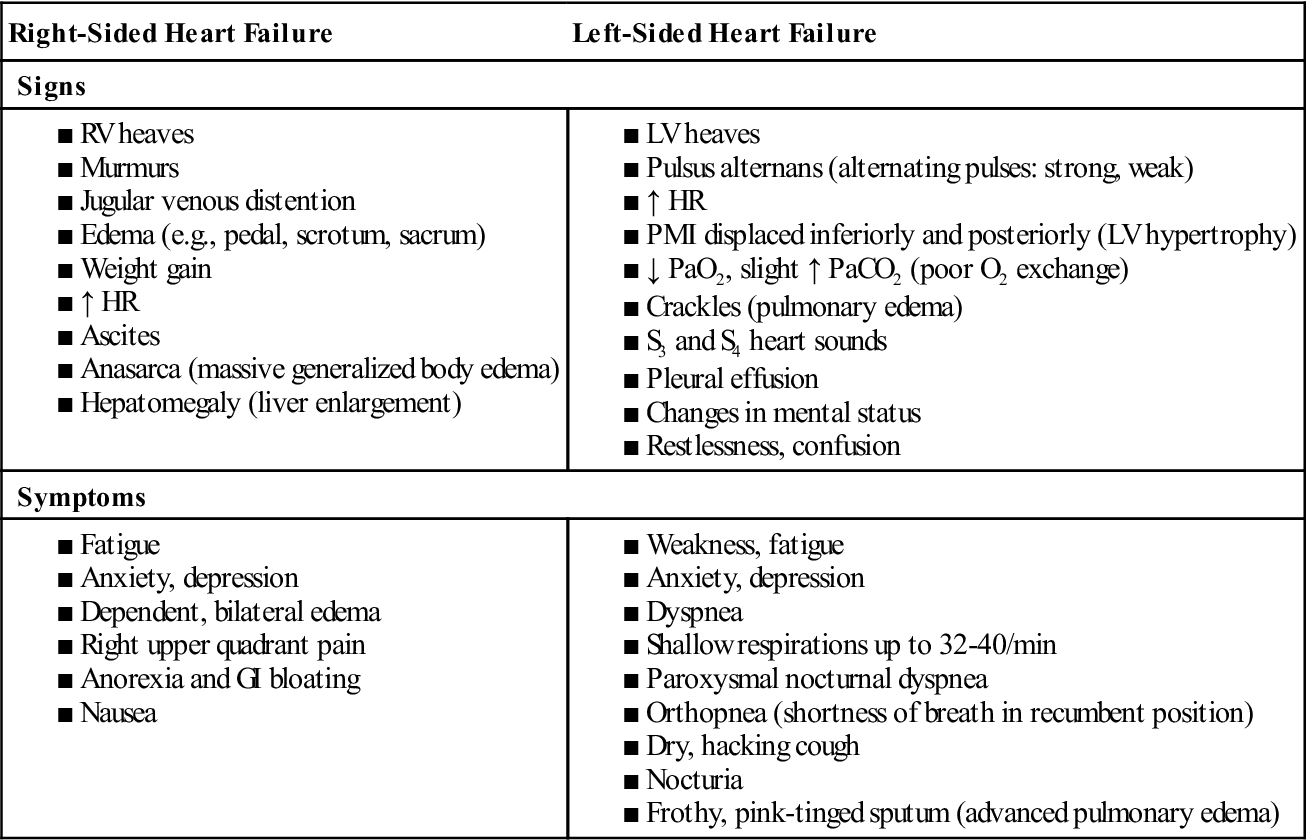

Chronic heart failure

Manifestations of chronic HF depend on the patient’s age, underlying type and extent of heart disease, and which ventricle is failing to pump effectively. Table 43 lists manifestations of left-sided and right-sided failure. The patient with chronic HF usually has manifestations of biventricular failure.

■ Fatigue after usual activities is one of the earliest symptoms.

Table 43

Manifestations of Heart Failure

| Right-Sided Heart Failure | Left-Sided Heart Failure |

| Signs | |

| Symptoms | |

Complications

Pleural effusion results from increasing pressure in the pleural capillaries. Enlargement of the heart chambers in chronic HF can cause atrial fibrillation. Patients also are at risk for ventricular dysrhythmias.

Left ventricular thrombus may occur with ADHF or chronic HF in which the enlarged LV and decreased CO combine to increase the chance of thrombus formation in the LV. This places the patient at risk for stroke.

Hepatomegaly may result as the liver becomes congested with venous blood. Hepatic congestion leads to impaired liver function; eventually liver cells die, and cirrhosis can develop. The decreased CO that accompanies chronic HF also results in decreased perfusion to the kidneys and can lead to renal insufficiency or failure.

Diagnostic studies

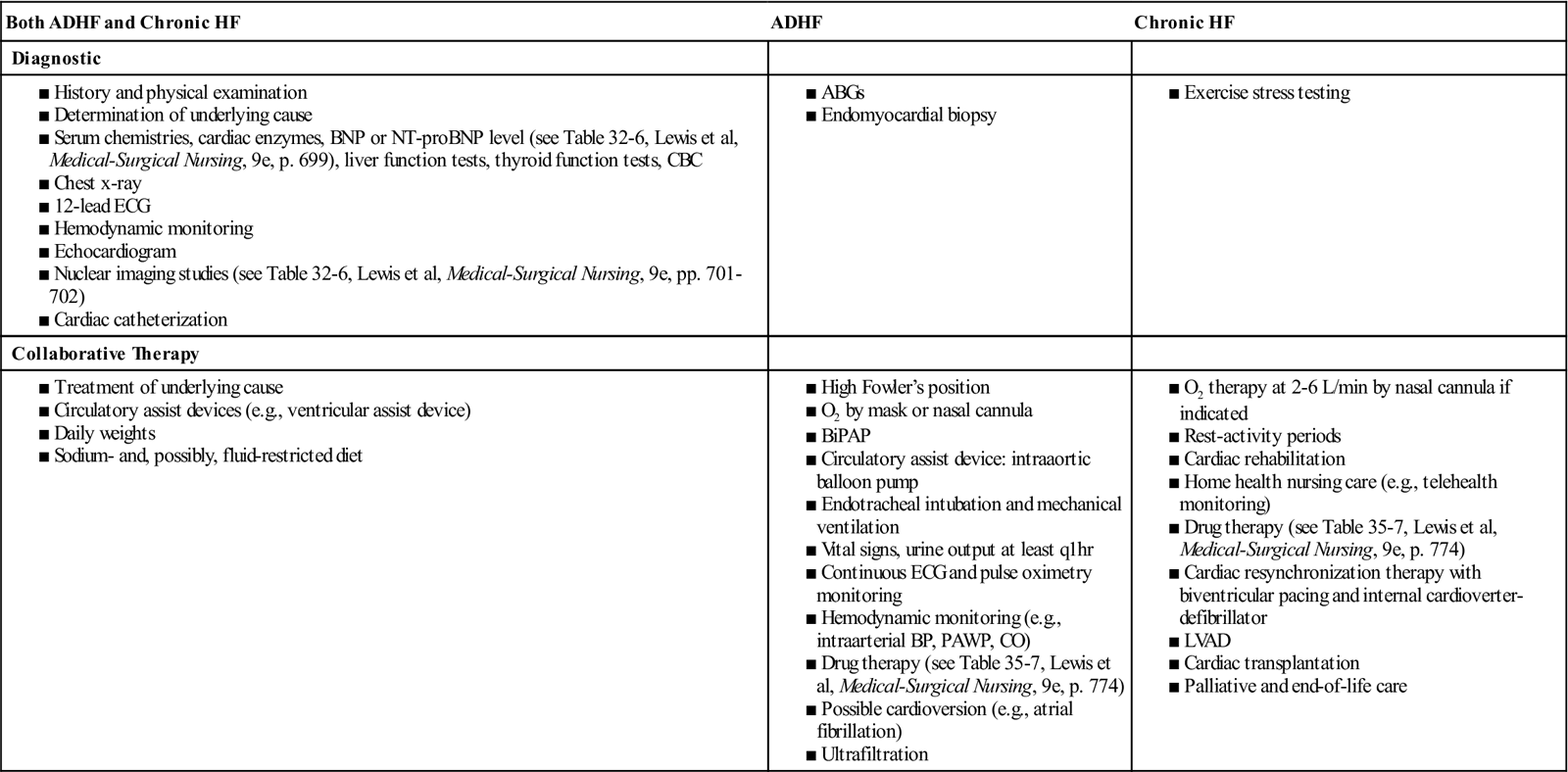

Diagnosing HF is often difficult because neither patient signs nor symptoms are highly specific, and both may mimic many other medical conditions (e.g., anemia, lung disease). Diagnostic tests for acute decompensated and chronic heart failure are presented in Table 44.

Table 44

Collaborative Care

Heart Failure

A primary diagnostic goal is to determine the underlying etiology. An endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) may be done in patients who develop unexplained, new-onset HF that is unresponsive to usual care. EF is used to differentiate systolic and diastolic HF. In general, b-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels correlate positively with the degree of left ventricular dysfunction.

Nursing and collaborative management: Acute decompensated heart failure

With the addition of new drugs and device therapies, the management of HF has dramatically changed in the past few years. Table 44 lists collaborative therapy for the patient with ADHF.

Patients with ADHF need continuous monitoring and assessment, which may be done in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting. Monitor ECG and oxygen saturation. The patient may have continuous hemodynamic monitoring. Supplemental oxygen helps increase the percentage of oxygen in inspired air. In severe pulmonary edema the patient may need noninvasive ventilatory support or intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Drug therapy

Drug therapy is essential in treating acute heart failure.

Digitalis is a positive inotrope that improves LV function but also increases myocardial oxygen consumption. Inotropic therapy is only recommended for use in the short-term management of patients with ADHF who have not responded to conventional pharmacotherapy (e.g., diuretics, vasodilators, morphine).

Collaborative care: Chronic heart failure

The main goals in the treatment of chronic HF are to treat the underlying cause and contributing factors, maximize CO, reduce symptoms, improve ventricular function, improve quality of life, preserve target organ function, and improve mortality and morbidity. The treatment of causes such as dysrhythmias, hypertension, valvular disorders, and CAD is discussed elsewhere in this book.

Nondrug therapy

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), unlike traditional pacing, coordinates right and left ventricular contractility through biventricular pacing. The ability to have normal simultaneous electrical conduction (synchrony) within the right and left ventricles increases left ventricular function and CO.

Mechanical options such as the IABP and ventricular assist devices (VADs) are available for patients with deteriorating conditions, especially those awaiting cardiac transplantation. Limitations of bed rest, infection, and vascular complications preclude long-term use of IABPs. VADs provide highly effective long-term support and have become standard care in many heart transplant centers.

Drug therapy

Nutritional therapy

Diet teaching and weight management are essential to the patient’s control of chronic HF. You or a dietitian should obtain a detailed diet history to determine not only what foods the patient eats but also when, where, and how often they dine out.

The edema associated with chronic HF is often treated by dietary restriction of sodium. Teach the patient what foods are low and high in sodium and ways to enhance food flavors without the use of salt (e.g., substituting lemon juice, various spices). The degree of sodium restriction depends on the severity of the HF and the effectiveness of diuretic therapy.

Fluid restrictions are not commonly prescribed for mild to moderate HF. However, in moderate to severe HF, fluid restrictions are usually implemented.

Nursing management: Chronic heart failure

Goals

The patient with HF will have a decrease in symptoms (e.g., shortness of breath, fatigue), decreased peripheral edema, increased exercise tolerance, adherence with medical regimen, and no complications related to HF.

See NCP 35-1 for the patient with HF, Lewis et al, Medical-Surgical Nursing, ed. 9, pp. 780 to 781.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing interventions

Help to aggressively identify and treat risk factors for HF to prevent or slow the progression of the disease. For example, teach a patient with hypertension or hyperlipidemia measures to manage BP or cholesterol with medication, diet, and exercise. Patients with valvular disease should have valve replacement planned before lung congestion develops.

Acute intervention.

Many people with HF will experience one or more episodes of ADHF. When they do, they are usually managed in an intensive care unit, an intermediate care unit with continuous cardiac monitoring capability, or a specialized HF unit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree