Gynecological Cancer

Cervical Cancer

DEFINITION

Cervical cancer consists of several cell types, but the most common, approximately 85% to 90%, are squamous cell carcinoma. Most of the remaining 10% to 15% are adenocarcinomas. Human papillomavirus (HPV) is strongly associated with cervical cancer, therefore leading to the conclusion that cervical cancer is a sexually transmitted disease associated with chronic infection by oncogenic types of HPV.

The main routes of spread of carcinoma of the cervix are as follows:

INCIDENCE

There are approximately 12,800 new cases per year and around 4,600 deaths per year in the United States. There are approximately 50,000 new cases of carcinoma in situ per year. The incidence appears to be less frequent in rural areas than in metropolitan areas; underdeveloped countries have a greater incidence of cervical cancer than that of developed countries. Approximately 93% are squamous cell cancers and contain HPV deoxyribonucleic acid; 90% of these are subtypes 16/18, which are the most virulent.

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Presenting symptoms may include the following:

• Increased amount and duration of regular thin, watery, blood-tinged vaginal discharge

• Painless spotting only postcoitally or after douching

• As the malignancy enlarges, bleeding episodes become heavier and more frequent. Menstrual flow eventually becomes continuous.

Late symptoms include the following:

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

If biopsy is necessary, patients should also have the following studies performed:

CLINICAL STAGING

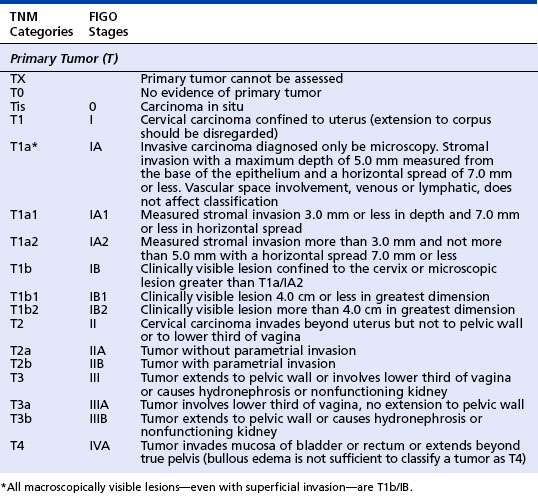

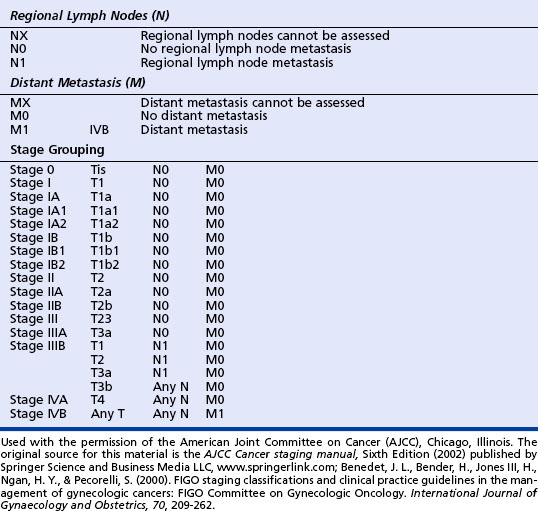

The staging of cervical cancer is a clinical appraisal. Because of the advantage of having several examiners and the benefit of muscular relaxation, pelvic examination under anesthesia is recommended. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system is widely used for cervical cancer. A parallel TNM staging system has been proposed by the American Joint Committee Commission on Cancer (see table on page 79).

TREATMENT

• Stage 0, carcinoma in situ (CIS), is often treated with a total hysterectomy. In cases where women wish to have more children, CIS may be treated conservatively with a therapeutic conization, laser ablation, or cryotherapy.

• Stage I and stage IIa cervical cancer may be treated with surgery or radiotherapy. Surgery for stage I and IIa may be reserved for young patients in whom preservation of ovarian function is desired and improved vaginal preservation is expected.

• Stages IIB and III tumors are best treated with concurrent chemoradiation or, in some cases, with irradiation alone. Radiation may be either external beam or brachytherapy. The chemotherapy of choice in this setting is cisplatinum. There are two rationales for using concurrent chemoradiation: (1) to increase the sensitivity of the tumor to the effects of the irradiation and (2) to eradicate systemic disease.

• Stage IVA disease (bladder or rectal invasion) can be treated either with irradiation or with pelvic exenteration.

• Combination chemotherapy involving bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cisplatinum, and methotrexate is used in patients where surgery and radiotherapy failed.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis for patients with cervical cancers varies greatly with factors including age, race, socioeconomic status, and general health at the time of diagnosis. Race and socioeconomic characteristics are believed to be factors because of greater exposure to other risk factors, more advanced disease at diagnosis, and the fact that these patients are less likely to undergo curative therapy.

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and Parallel TNM Staging System Proposed by American Joint Committee on Cancer: Cervical Cancer

Five-year survival by stage is as follows:

American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Practice recommendations: practice management. Retrieved on May 20, 2006, from http://www.asccp.org/edu/practice/cervix/cancer.shtml, 2005.

Denny L., Hacker N.F., Gori J., et al, eds. Staging classifications and clinical practice guidelines for gynaecologic cancers. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 3rd ed., 70. Elsevier, 2000;207–312.

Greene F., Page D., Fleming I., et al. AJCC cancer staging handbook, 6th ed., New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

Stehman F.B., Perez C.A., Karman R.J., et al. Uterine cervix. In: Hoskins W.J., Perez C.A., Young R.C., et al. Principles and practice of gynecologic oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:743–767.

National Cancer Institute. Human papillomavirus vaccines. Retrieved May 20, 2006, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd, 2006.

Zorab R., et al. Invasive cervical cancer. In: DiSaia P.J., Creasman W.T. Clinical gynecologic oncology. St. Louis: Mosby; 2002:53–61.

Endometrial Cancer

DEFINITION

Endometrial cancer arises from the lining of the uterus. It is primarily a disease of the postmenopausal woman; only 25% of the cases occur in premenopausal patients, and in most cases the tumor is confined to the uterine corpus (body of the uterus) at the time of diagnosis. A small percentage are sarcomas arising from either endometrial glands and stroma or from the uterine muscle (leiomyosarcoma). The usual carcinoma of the endometrium is easily diagnosed, but the well-differentiated cancers may be difficult to separate from advanced atypical hyperplasia. In the past 10 years, helpful criteria have been adopted to permit differentiation of the two conditions into a benign lesion (atypical hyperplasia) and a neoplasm that is progressive (well-differentiated carcinoma).

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Factors for increased risk of endometrial carcinoma include the following:

CLINICAL STAGING

The prognostic value of surgicopathologic staging has been confirmed in multiple studies of large numbers of patients. Stage of the disease is often the single strongest predictor of outcome for women with endometrial adenocarcinoma. See the box on page 81 for the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system for endometrial carcinoma.

PROGNOSIS

Many patients with endometrial adenocarcinoma have a mixture of good and bad prognostic factors and do not fall into categories for which either the prognosis or need for adjuvant therapy is clear. It should be noted that the survival for most women with early surgical stage disease is excellent. The 1-year relative survival rate is 94%; the 5-year survival rate for patients with stage I-IIA disease is 96%, for stage IIB-IIIB it is 66%, and for stage IIIC-IV disease it is 25%. Essentially all reports agree that differentiation (grade) of tumor and depth of invasion are important prognostic considerations.

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Classification of Endometrial Carcinoma

| IA G1,2,3 | Tumor limited to endometrium |

| IB G1,2,3 | Invasion to less than half of the myometrium |

| IC G1,2,3 | Invasion to more than half of the myometrium |

| IIA G1,2,3 | Endocervical glandular involvement only |

| IIB G1,2,3 | Cervical stromal invasion |

| IIIA G1,2,3 | Tumor invades serosa or adnexa or positive peritoneal cytologic findings |

| IIIB G1,2,3 | Vaginal metastasis |

| IIIC G1,2,3 | Metastasis to pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes |

| IVA G1,2,3 | Tumor invades bladder or bowel mucosa |

| IVB | Distant metastasis including intra-abdominal or inguinal lymph nodes |

| HISTOPATHOLOGY: DEGREE OF DIFFERENTIATION | |

| Cases of carcinoma of the corpus should be grouped according to the degree of differentiation of the adenocarcinoma as follows: | |

| G1 | 5% or less of a nonsquamous or nonmorular solid growth pattern |

| G2 | 6% to 50% of a nonsquamous or nonmorular solid growth pattern |

| G3 | More than 50% of a nonsquamous or nonmorular solid growth pattern |

Data from Benedet, J.L., Bender, H., Jones, H., 3rd, Ngan, H.Y., & Pecorelli, S. (2000), FIGO staging classifications and clinical practice guidelines in the management of gynecologic cancers. FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. International Journal of Gynaecol-ogy and Obstretics, 70(2), 206–62.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree