CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Governance of practice and leadership

Implications for nursing practice

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

demonstrate an understanding of the conceptual link between models of professional practice and governance of practice;

demonstrate an understanding of the conceptual link between models of professional practice and governance of practice;MODELS OF GOVERNANCE AND CONTROL OF PRACTICE

The concept of governance of practice has long been associated with the professions and the professional role (Bixler & Bixler 1966). This obligation carries with it the need for health professionals to be responsible for controlling the quality of their practice through oversight and monitoring, so as to ensure high quality care (Alfano 1971; Larson 1977; O’Rourke 1976). A variety of models of governance have emerged to assist professionals meet this obligation and play an important role in health care planning, improving care delivery and ensuring quality care. In the United States, shared governance is a common term, whereas in the United Kingdom the key concepts of shared governance are subsumed under the term clinical governance. In Australia, the term clinical governance is more prevalent. It is important, however, to distinguish between the different models of governance as each has its own variation and individual characteristics. In the United States, the term ‘shared governance’ is sometimes viewed with skepticism by some levels of management, which see it as a possible intrusion into operations and corporate authority.

Shared governance is defined as a decentralised approach to organisation and management that gives nurses a greater autonomy over their practice and workplace (O’May & Buchan 1999; Porter-O’Grady 1995; 2001; Prince 1997). This approach serves as a framework to support empowerment processes in clinical decision-making for nurses, and represents an excellent opportunity for nurses to play a leading role in health care planning, delivery and evaluation. This framework establishes processes by which professional staff in the workplace can participate in decisions that affect their practice, professional development and work environment. The trend towards governance mechanisms has emerged in response to a need for health professionals to take responsibility for their practice, monitor outcomes and to work together to achieve optimal outcomes. This is also in response to a perception of the failure of traditional, hierarchical models and the seduction of charismatic leadership. The importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and communication is underscored in models of clinical governance (Swage 2000).

To implement a mechanism of governance, organisational changes and mechanisms for participation in the decision-making process need to be established. In a hospital that implements shared governance, nurses are able to share information and opinions, increase responsibilities and improve their education, thereby increasing the opportunity to provide better patient care. Porter-O’Grady (2001) challenges health care systems to more effectively create their own destinies, and challenges leaders to develop new ways of thinking, knowing and doing, because he asserts this change of focus will improve health outcomes. It is important to remember that the underlying principle related to governance is ensuring that standards of professional practice are upheld.

Another model, termed clinical governance, has achieved considerable momentum with many nurses playing key roles in the decision-making of the health care system. Clinical governance means that there is organisational accountability for clinical performance, health outcomes and effective use of resources, including systems that regulate clinical activity, ensure patient safety and promote the highest standards of patient care (Swage 2000). In this approach, through an organised structure clinicians can be held accountable to make cost-effective choices that do not undermine the standard of practice or care. Clinical governance allows clinicians to work closely with management to identify and manage resources. In this chapter the discussion of clinical governance focuses upon the clinical practice setting.

WHY CLINICAL GOVERNANCE?

A recent report (Aiken et al. 2000) documents widespread nurse dissatisfaction with management. These authors report nurses feeling undervalued by management and not provided with adequate professional opportunities. Mechanisms of governance can likely overcome these concerns and become an impetus for recruitment and retention of nurses.

The professional work that nurses are authorised to do can be accomplished through governance structures (O’Rourke 1976, 1979, 1985, 1989, 2001). Professional practice is authorised and controlled on a range of levels from licensure at a government level to development of professional standards of practice by professional and specialty organisations, as well as through individual practitioner commitment to a code of ethics (ICN 2002). In order to implement an accountability-based practice model, management must institute structures that support the core business of patient care delivery (O’Rourke 2001). Further, management must nurture work environments that empower individuals to deliver patient care in an effective and efficient manner. In health care the professional disciplines, such as medicine and nursing, assume the important role of leader and decision-maker on the care team. These professionals require an environment that supports this professional work. Professional disciplines exercise powerful authority over the course of action to be taken and the impact on patient outcomes. Thus, it is important when discussing professional work to understand the essential elements of the professional role and its primary obligation to use standards to govern practice. Implicit in this role, professional work carries with it the requirement for monitoring and evaluating clinical practice to ensure the highest levels of quality (O’Rourke 1985, 1989).

The genesis for these role obligations is the definition of a profession which is defined as an occupation with special power and prestige granted by society because of the occupation’s competence in esoteric bodies of knowledge that are linked to the central needs and values of the social system (Larson 1977). The three key dimensions of a profession derived from this definition include:

the normative dimension, which includes the service orientation and ethics that justify the privilege of self-regulation. The profession regulates itself through professional standards of practice as well as statutory and regulatory bodies;

the normative dimension, which includes the service orientation and ethics that justify the privilege of self-regulation. The profession regulates itself through professional standards of practice as well as statutory and regulatory bodies; the evaluative dimension, which includes autonomy and control of professional activity and monitoring of standards of practice. It is here that the governance structure of an organisation assists professionals to meet their role obligations and carry out their work; and

the evaluative dimension, which includes autonomy and control of professional activity and monitoring of standards of practice. It is here that the governance structure of an organisation assists professionals to meet their role obligations and carry out their work; and the cognitive dimension, which includes the body of knowledge and techniques that are applied in practice, with necessary training and skill to master such knowledge.

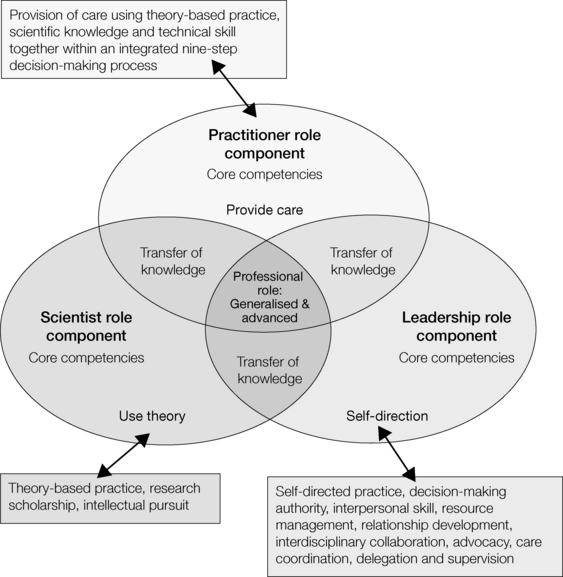

the cognitive dimension, which includes the body of knowledge and techniques that are applied in practice, with necessary training and skill to master such knowledge.Health professionals are bound by obligations, and governance structures help them keep their commitment to the public to deliver high quality care (Curtain 2000). Adherence to professional obligations provides the role authority for nurses and other professional disciplines to act on behalf of the patient. The professional role and role expectations, depicted in Figure 22.1, illustrate the rationale for governance of practice (O’Rourke 2001).

O’Rourke’s model is based on three professional role components: scientist, leader and practitioner. These factors function to form a dynamically integrated set of expectations and competencies. From these three components are derived the expected role capacities of self-direction, theory-based practice, transfer of knowledge and provision of care (Alfano 1971; O’Rourke 1980, 1989, 2003). The three role elements are performed in concert so as to act synergistically with one another within one role and one person. These components cannot be separated.

This integrated set of expectations constitutes the professional role and expectations that are to be upheld, irrespective of the functional role held, such as staff nurse or educator. O’Rourke (2001) cautions not to turn these three role components into discrete, functional roles and assign them a job title. For example, one does not have to be hired as a nurse researcher to identify with the characteristics of a scientist and to demonstrate scientific accountability. Further, a registered nurse (RN) does not have to be in charge of the unit to demonstrate leadership in practice. Influencing care decisions through clinical leadership is an inherent part of the professional role, irrespective of the location or level practised by the RN.

Using these three components in dynamic interaction is a key competency of the professional role, irrespective of the discipline, particular role or specific job title. Nurses must be educated and socialised to see themselves in the role of scientist–practitioner–leader, a role that is prescribed for members of a profession. These considerations have significant implications for the education and preparation of nurses.

PROFESSIONAL ROLE AUTHORITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY

An understanding of this model is particularly important because currently in health care a narrow view of the professional nursing role is being portrayed. This view describes a nurse as a practitioner who plans and supervises the implementation of tasks, generating an incomplete picture. When described in this way, nursing is not viewed as an intellectually-based practice discipline. This view de-emphasises the important value of our role to advance the cause of health and limits the consumer’s understanding of our practice. The International Council of Nurses’ (2002) definition of nursing includes promotion of health, prevention of illness and care of ill, disabled and dying patients. It is these goals and not the tasks that frame our thinking about what to do and how to do it.

Engaging in scholarly activity is essential for nurses, so that as key members of the team they can generate the science that helps determine whether their actions are helping people cope and manage their health and illness problems. Using nursing science within the team helps us to be better clinical leaders in directing and coordinating care and care delivery. The current overemphasis on the ‘how to’ and ‘practical’ thinking side of our practice obscures our larger social value as a profession. The ‘how to’ tasks must be performed in support of the goal of nursing, which is our independent function, and in support of the medical goal, which is our dependent function. Moreover, this incomplete and narrow view undermines the complexity of our professional role that stems from the interaction of the three professional role components; in this case the sum of the integration of practitioner, scientist and leader is more complex than each of the parts individually. Our practice authority stems from our public assertion as a profession that we use a substantial amount of scientific knowledge, not tradition, to direct our action. Hence, the increasing importance of nursing research and evidence-based practice. Without this overriding professional image, our practice authority and clinical leadership role to manage decisions that set the direction for recovery and coordinate patient care is compromised (Blegen et al. 1998).

In the United States, O’Rourke (1994, 2001, 2003) has used a professional practice model as the clinical practice system for establishing a role and standards-based practice, and for linking performance to the practice standard with patient outcomes.

PROFESSIONAL ROLE DECISION-MAKING AUTHORITY AND PROCESS

The professional role and its leadership position on the team is founded on the concept of self-direction which is made operational through the rigorous application of a nine-step decision-making process for which the professional role is accountable. The elements of this professional decision-making process are depicted in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1 O’Rourke Model of Professional Role Competence: Putting it all together as practitioner–scientist–leader. Professional practice requires nine core competencies

| Professional Practice Process | |

|---|---|

| Six competencies | |

| Seventh competency | |

| Eighth competency | |

| Ninth competency | 9. Dynamic integration of previous eight steps using

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|