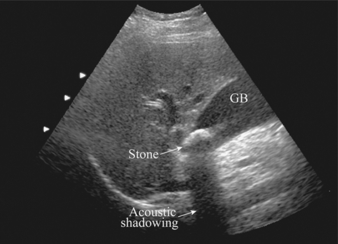

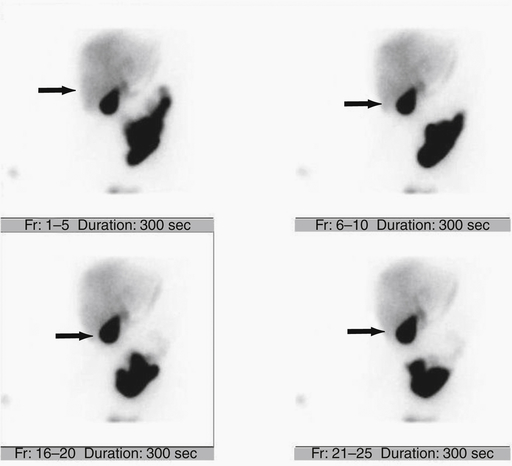

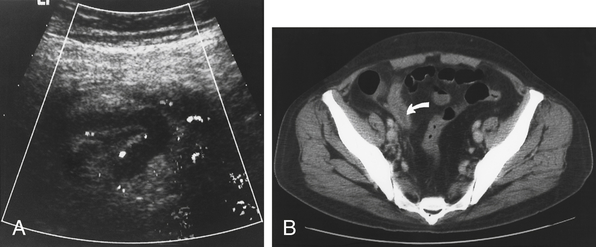

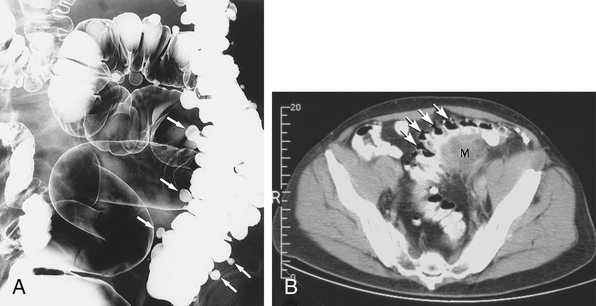

Chapter 13 Ultrasound is the best first imaging study for suspected gallbladder disease (Fig. 13-1). It may show gallstones, a thin layer of fluid around the gallbladder, and/or a thickened gallbladder wall. A more specific ultrasonographic Murphy sign using direct visualization of the gallbladder can be obtained (variant anatomy and significant obesity can create uncertainty). A nuclear hepatobiliary scintigraphic study (e.g., hepato-iminodiacetic acid [HIDA] scan) clinches the diagnosis with nonvisualization of the gallbladder (Fig. 13-2). The treatment is pain control and cholecystectomy (antibiotics may be indicated if infection is suspected); a laparoscopic approach is generally preferred over an open procedure. Appendicitis classically presents in 10- to 30-year-olds with a history of crampy, poorly localized periumbilical pain followed by nausea and vomiting. Then the pain localizes to the right lower quadrant, and peritoneal signs develop with worsening of nausea and vomiting. It is said that a patient who is hungry and asking for food does not have appendicitis (called the “hamburger” sign). A classic clue to the diagnosis is Rovsing sign: when you palpate a different quadrant and then quickly release your hand, the patient feels pain at McBurney point (two thirds of the way from the umbilicus to the anterior superior iliac spine). McBurney point is the area of maximal tenderness in the right lower quadrant and the site where an open appendectomy incision is made. CT is increasingly used to confirm the diagnosis before surgery in stable patients (Fig. 13-3). Colonoscopy should not be performed in the acute setting because colon rupture may occur; barium enema is also avoided for the same reason. However, one of these tests should be done in every patient after treatment to exclude colon carcinoma. Order a CT scan, if necessary, to confirm a diagnosis of diverticulitis (Fig. 13-4).

General Surgery

4 Specify which conditions are associated with pain and peritonitis in the listed abdominal areas.

AREA

ORGAN (CONDITIONS)

Upper right quadrant

Gallbladder/biliary (cholecystitis, cholangitis) or liver (abscess)

Upper left quadrant

Spleen (rupture with blunt trauma)

Lower right quadrant

Appendix (appendicitis), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Lower left quadrant

Sigmoid colon (diverticulitis), PID

Epigastric area

Stomach (peptic ulcer) or pancreas (pancreatitis)

7 How is a clinical suspicion of cholecystitis confirmed and treated?

9 Describe the classic presentation of appendicitis. How is it treated?

11 What tests should and should not be done to confirm possible cases of diverticulitis? What test does every patient need after a treated episode of diverticulitis?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree