Gastrointestinal System

Anal Cancer

DEFINITION

Anal cancers are uncommon tumors located in the anus. The anus is the proximal end of the large intestine that connects to the outside of the body. It measures approximately an inch and a half and opens to allow passage of stool from the body.

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

• HPV, particularly HPV type 16, may be implicated in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the anus

• Multiple sex partners is a risk factor for women

• Engaging in anal intercourse is a risk factor for both men and women

• Smokers are at a four-times-higher risk for development of anal cancer than are those who never smoked

• Immunocompromised people who have undergone transplants or have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are at greater risk

• Long-term medical problems in the anal area such as anal fistulas or other benign conditions increase risk

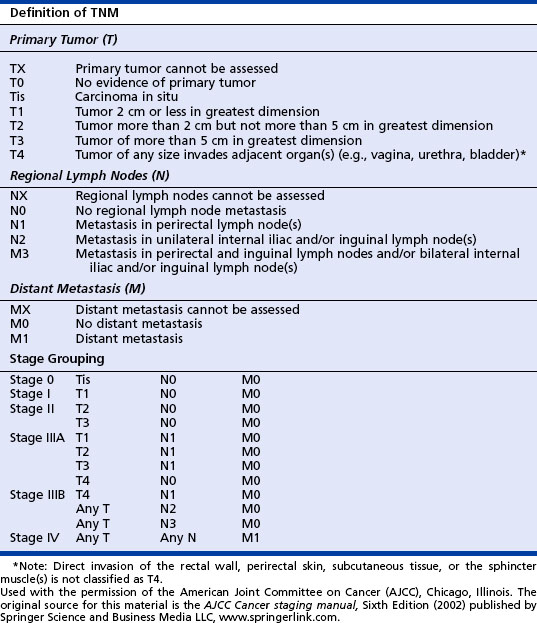

CLINICAL STAGING

Clinical staging is essential for determining extent of disease and associated treatment strategies. Staging is done using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) system (see table on page 51).

TREATMENT

• Local resection involves removal of only the tumor with a slim margin of noncancerous tissue around the tumor

• Abdominoperineal resection is an extensive procedure used in treatment of cancer of the anal canal. After this procedure, patients will have a permanent colostomy. This procedure can often be avoided by using chemoradiation

The chemotherapy agents used to treat anal cancer are as follows:

PREVENTION

The causes of many anal cancers remain unknown. Because HPV and HIV infections are known risk factors for the development of anal cancer, reduction in sexual practices that carry a high risk for contracting these infections should be used. Practices to avoid include the following:

American Cancer Society. Learn about cancer, anal cancer. Retrieved December 1, 2006, from www.cancer.gov, 2006.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2007, from www.cancer.org, 2007.

Anal cancer. In: Greene F., Page D., Fleming I., et al. AJCC cancer staging handbook. 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002:126–127.

Minsky B.D., Hoffman J.P., Kelson D.P. Cancer of the anal region. In: DeVita V.T., Hellman S., Rosenberg S.A. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1319–1342.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology-rectal cancer. version 1.2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007, from http://www.NCCN.org, 2007.

Biliary (Extrahepatic Bile Duct) and Gallbladder Cancers

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

• Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

• Imaging studies: abdominal ultrasonography, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography

• Blood work: complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, liver function tests, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9

HISTOLOGY

• The presence of in situ carcinoma in the ducts near the tumor

• Modulation from bile duct to parenchyma liver cells (cells resemble biliary epithelium without bile production versus hepatocytes from the liver)

• Ducal plate configuration within the tumor

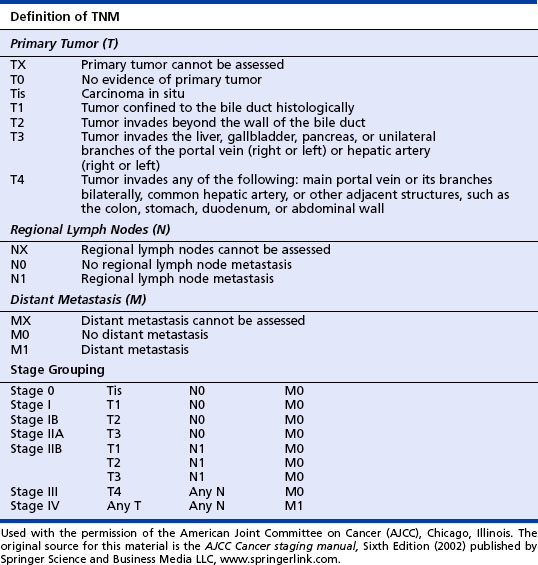

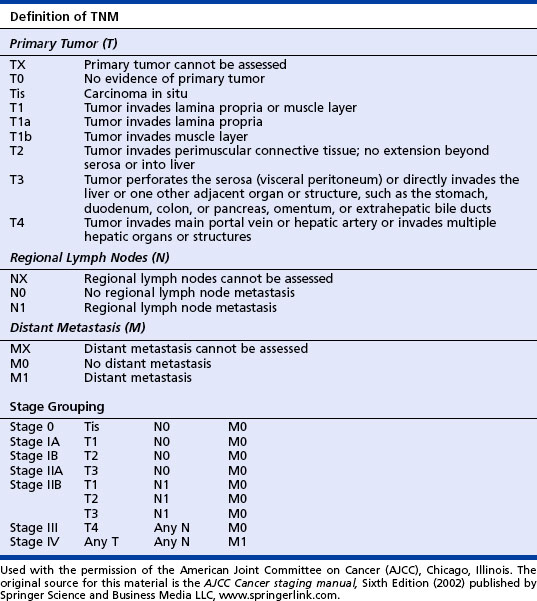

CLINICAL STAGING

Staging is clinically based and is the best possible estimate of the extent of disease before treatment. Staging should be done by the TNM classification published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. See the tables on pages 52 and 53.

TREATMENT

Extrahepatic Bile Duct

• Classified as being resectable or unresectable

• Surgical procedure varies according to location of tumor and is usually extensive (i.e., Whipple procedure) with a 5% to 10% mortality rate and a cure rate of ≈5%.

• Palliative surgical interventions are similar to those for cancer of the gallbladder.

• External beam radiation may be used in conjunction with surgical intervention.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2007, from http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/stt_0.asp, 2007.

Coleman J. Gallbladder and bile duct cancer. In: Yarbro C.H., Frogge M.H., Goodman M. Cancer nursing principles and practice. 6th ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2005:1276–1291.

Greene F., Page D., Fleming I., et al. AJCC cancer staging handbook, 6th ed., New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002.

National Cancer Institute. Gallbladder cancer. Retrieved on January 28, 2007, from http://cancernet.nci.nih.gov/cancertopics/pdq/prevention/oral/healthprofessional, 2006.

National Cancer Institute. What you need to know about extrahepatic bile duct cancer. Retrieved on June 2, 2006, from www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/oral, 2006.

Colon and Rectal Cancer

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

• The risk for development of CRC increases with age. Ninety percent of cases are diagnosed in individuals more than 50 years old.

• Risk is increased in individuals with a personal or family history of colon cancer or polyps or a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease. Inherited genetic syndromes including familial adenomatous polyposis and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer are associated with significantly increased risk for development of CRC.

• Additionally, modifiable risk factors in personal lifestyle and environmental exposures contribute to the risk for development of sporadic CRC. These include obesity; a diet high in fat, red meat, or processed foods and low in fruits and vegetables; heavy alcohol consumption; smoking; and physical inactivity.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Presenting symptoms may vary depending on the location of the tumor:

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

• If CRC is suspected a comprehensive general history should be obtained. Individual and family risks, prior surgery, medical history, and social factors are critical components. Family history of cancer including type of cancer (especially colorectal, uterine, ovarian, ureter, or bladder) and age at diagnosis are important factors in identifying potential hereditary or familial syndromes. Thorough review of systems can provide insight to early or late signs of malignancy.

• A complete physical examination with emphasis on lymph nodes, abdomen, breast, and rectum should be performed.

• Laboratory tests should include a complete blood cell count, liver function tests, coagulation profile, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). CEA is a glycoprotein that is present in gastrointestinal mucosa cells. Overexpression is suspicious for malignancy. It is not a tumor marker but rather a tumor-associated marker.

• Endoscopic examination is performed after the completion of the history and physical examination when a better sense of tumor location may be identified. Methods include a sigmoidoscopy, either flexible, which allows visualization to just above the rectosigmoid junction (20 cm), or a rigid sigmoidoscopy, which visualizes to the proximal end of the sigmoid colon (60 cm). A colonoscopy visualizes the entire colon. Biopsy of the tumor can be obtained at this time.

• Transrectal ultrasonography is a good tool for staging rectal carcinomas.

• A noninvasive examination of the colon can be performed with a double contrast barium enema.

• Diagnostic imaging studies are completed to ascertain the presence of metastatic disease. Chest x-ray examination is appropriate at time of diagnosis if computerized tomography (CT) of the chest has not been obtained. CT of the abdomen and pelvis can determine the presence of extracolonic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging is a good follow-up to questionable findings in the liver on CT.

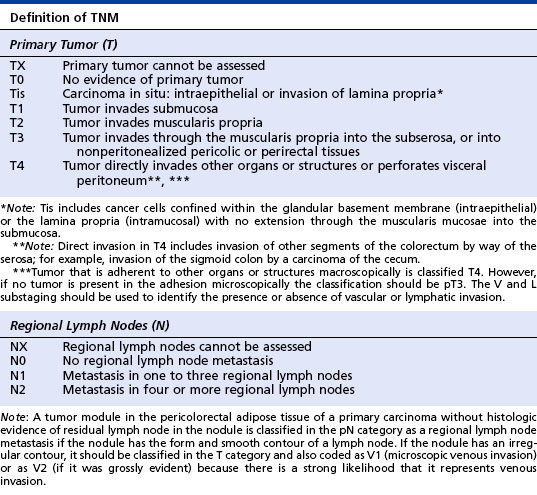

CLINICAL STAGING

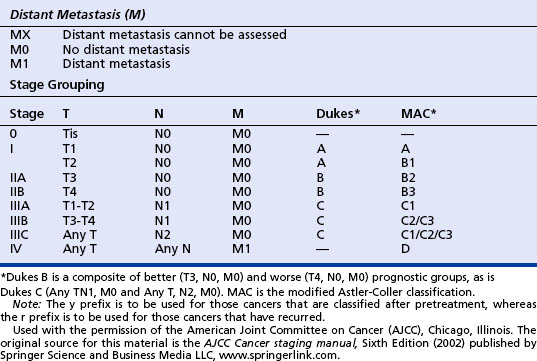

Accurate staging is essential for adjuvant treatment decision making and development of prognosis. Staging is done according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines by the TNM classification system (see table on page 55). In CRC, staging relates to the depth of tumor invasion through the bowel wall, involvement of regional lymph nodes, and the presence of distant metastasis.

TREATMENT

Colon Cancer

• Surgical removal of the primary tumor and lymph node resection is the initial therapy. If there is presence of synchronous metastasis that is deemed unresectable at any point along the cancer trajectory, a limited colon resection to relieve blockage may be performed.

• Adjuvant chemotherapy depends on the stage of disease and the prognostic risk factors.

• Approved chemotherapy regimens for stage II and stage III disease include the following:

• Approved treatment for stage IV or recurrent disease includes the following:

• Radiation therapy (RT) has a limited role in colon cancer. It may be recommended for patients who have had a bowel perforation in attempt to improve local control. Additionally, it may be used for palliation of painful metastasis.

Rectal Cancer

• Surgical resection by either a transanal or a transabdominal approach is primary treatment for T1-2 lesions in the low rectum.

• Neoadjuvant chemoradiation may be used to reduce the tumor size before surgery for T3, T4, or T1-4 lesions with nodal involvement.

• Adjuvant chemotherapy should be given for at least 6 months after surgery for all patients who received preoperative therapy regardless of pathological staging.

• Combined modality neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer is as follows:

• Adjuvant therapy and therapy for metastatic or recurrent rectal cancer includes regimens outlined in the treatment of colorectal cancer.

PREVENTION

Modifiable lifestyle prevention strategies include the following:

• Eating more fruits and vegetables

• Reducing high-fat foods, particularly animal fat

• Minimizing alcohol intake, avoiding beer and beverages with a high percentage of alcohol that contain nitrosamines, which can be carcinogenic to the colon

• Maintaining weight within healthy range

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree