Chapter 18 Gastrointestinal disorders in HIV including diarrhea

Gut-Associated Lymphatic Tissue (GALT)

Recent research has emphasized the importance of the GALT in the pathogenesis of HIV in the gut, in the liver, and in the body overall. The primary target of HIV is the CD4 T cell compartment and the GALT contains the largest number of lymphocytes of any organ in the body, approximately 80% of the entire T cell population. The majority of gut and peripheral CD4 T cells are lost during the acute phase of HIV [1, 2]. This depletion of gut CD4 T cells and the resulting altered mucosal immunity persist into the chronic phase and despite effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) and peripheral CD4 T cell recovery [3–5]. This breach in the integrity of the gut mucosa allows bacteria and bacterial products, such as the endotoxins lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to cross over and reach the portal and systemic circulations. This process, referred to as microbial translocation, may contribute to the pro-inflammatory state characterizing chronic HIV infection [6]. Microbial translocation also occurs in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is involved in its pathogenesis [7]. In a study of 26 patients with AIDS with a CD4 count < 300 cells/mm3 and high plasma LPS levels, 65% of patients had at least one positive serological marker of IBD when tested for ASCA (anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody); pANCA (perinuclear anti-neutrophil antibody); anti-OmpC (antibody against outer membrane porin C of E. coli); and anti-CBir1 (antibody against bacterial flagellin) [8]. Forty-six percent of patients had an IBD-like serological pattern; 75% of them had a Crohn’s disease-like pattern. This suggests that IBD markers may be useful for monitoring HIV-related inflammatory gut disease and requires further study. Massive depletion of the gut T cells may also make the gastrointestinal tract more susceptible to common pathogens.

Esophageal Disorders

The epidemiology of esophageal disorders has changed in parallel with ART-induced immune reconstitution and consequent aging of the HIV-infected population. Opportunistic GI disease has decreased significantly with combination ART (cART) [9]. In the developed world, HIV-infected patients presenting with esophageal symptoms often receive diagnoses similar to that of an immunocompetent host [10]. Dysphagia and odynophagia were common complaints of HIV-infected patients prior to cART [11]. Most of the time, the etiology was Candida esophagitis and, not infrequently, esophageal ulcers caused by either CMV or herpes simplex virus (HSV), or were idiopathic. Today, most patients have good control of their HIV infection with suppressed HIV RNA and CD4 T cell counts > 200 cells/mm3. Reflux symptoms are a major complaint and patients are found to have inflammatory gastropathy, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Helicobacter pylori infections, Barrett’s esophagus, and gastric ulcers [11]. Since the HIV population is aging, these are all appropriate illnesses for these patient’s age groups. In a given patient, the differential diagnosis depends on the degree of immunosuppression, reflected by the CD4 count, but also on other specific risk factors associated with each condition.

Although cART can help restore immunity and prevent opportunistic infections, those not taking ART, not adherent to ART, failing ART, or not optimally responding to ART may present with upper GI complaints and CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3 [12]. Among these patients, upper endoscopy is diagnostic in about 75% of cases [13]. Opportunistic infections are likely involved and should be ruled out. Candida esophagitis caused by Candida albicans is the most common. (See Chapter 15 on oropharyngeal candidiasis.) At endoscopy, the typical appearance of the esophagus is hyperemic with yellow-white mucosal plaques that, when removed, uncover a friable mucosa. For Candida esophagitis, upper endoscopy with biopsy and culture is the diagnostic method of choice, although when presentation is highly suggestive of it, antifungal therapy can be attempted first [14]. Oral fluconazole is the drug of choice [15], but intravenous (IV) fluconazole can be used as needed. Other azoles (itraconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole) and echinocandins (caspofungin, micafungin, anidulafungin) are also effective against Candida and can be used in certain cases [14]. Advanced immunosuppression, especially with CD4 counts < 50 cells/mm3, increases the risk of developing refractory candidiasis that has a poor prognosis [16]. Refractory candidiasis is usually defined as mucosal candidiasis that fails to resolve despite 7–14 days of daily fluconazole (≥ 200 mg daily). Long-term exposure to azole antifungal agents also predisposes to selection of fluconazole-resistant Candida strains, such as C. glabrata and C. krusei, although most cases of refractory candidiasis are caused by C. albicans with high minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) to fluconazole [16]. Esophageal candidiasis should also be suspected when other risk factors are present whether the CD4 count is above or below 200 cells/mm3. These risk factors include acute HIV infection, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, corticosteroids, diabetes mellitus, and immunosuppression due to leukemia, lymphoma, transplantation, or antineoplastic agents. Primary and secondary (except when recurrences are frequent or severe) prophylaxis of mucosal candidiasis disease are not recommended because of the low mortality of the disease, effectiveness of therapy in the acute setting, and the risk for development of antifungal resistance [14].

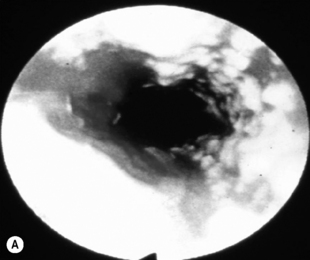

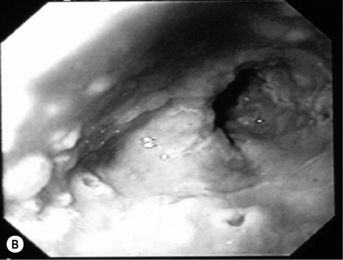

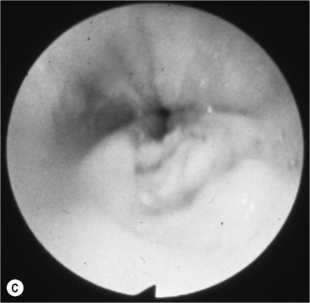

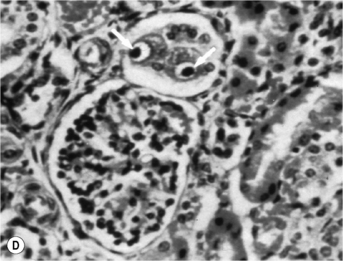

When the CD4 count decreases < 100 cells/mm3, other pathogens are found alone or, most commonly, in association with candidiasis such as HSV and, as immunosuppression further increases, CMV, mycobacterial infections, and other opportunistic pathogens, at a lesser frequency (Fig. 18.1A). Symptoms from HSV and CMV esophagitis are similar to candidiasis. Dysphagia, odynophagia, nausea, fever, and epigastric pain are the most common presenting symptoms. The diagnosis of HSV esophagitis is made at upper endoscopy. Classically, multiple small superficial ulcers with or without vesicles are seen in the distal third of the esophagus (Fig. 18.1B) [17]. Recovery of the virus in culture is diagnostic, although typical herpetic lesions can be seen on biopsy as well. Although HSV-1 is found in the majority of cases, HSV-2 has been reported [17]. Acyclovir, oral, or IV is the usual treatment. CMV esophagitis is also diagnosed at upper endoscopy. Unique or multiple large, shallow ulcers in the middle or distal esophagus are seen (Fig. 18.1C) [18]. Culture is neither sensitive nor specific. Definitive diagnosis is made by (1) histopathology showing large intranuclear inclusions with an owl-eye appearance (Fig. 18.1D) and (2) positive immunohistochemical or direct fluorescent staining techniques for CMV. Treatment is oral valganciclovir or IV ganciclovir. Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), caused by human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8), is more common at CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3, but can occur at any CD4 count. Treatment of esophagitis in the HIV immunosuppressed patient should also include timely instituted cART. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of specific opportunistic infections in HIV-infected patients are available [14]. Idiopathic (aphthous) ulcerations of the esophagus are found in approximately 5% of patients with AIDS and esophagitis [19]. Thalidomide and corticosteroids have been used to treat these [20]. HIV-infected patients without immunosuppression presenting with upper GI complaints can be evaluated the same way as immunocompetent hosts.

Gastric Disorders

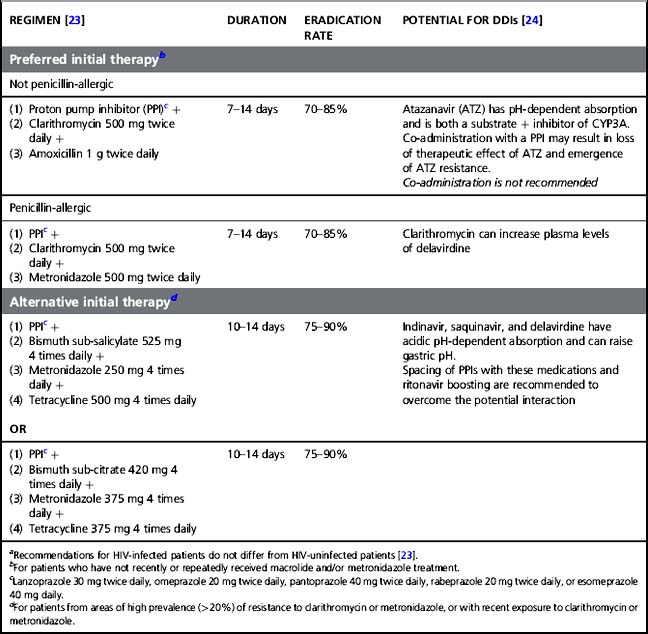

The most common gastric disorders diagnosed in HIV patients are similar to those seen in non-HIV-infected patients although opportunistic infections must be considered, especially in those with lower CD4 counts. Helicobacter pylori infections are often identified in HIV-infected patients and can lead to gastritis and gastroduodenal ulcers in these patients, similar to the general population. Helicobacter pylori is a small, microaerophilic, curved rod that has the ability to live and multiply in the acid gastric milieu, establishing colonization or infection. Data on incidence of H. pylori infections among HIV-infected patients compared to the general population are conflicting, but it seems that patients with AIDS have a lower incidence than HIV-infected patients without AIDS or HIV-uninfected patients [21]. The cause for this is unknown. It may be explained by repetitive antibiotic treatments in AIDS patients and widespread use of antacids medications for upper GI symptoms [22]. Helicobacter pylori is usually diagnosed by serology, urea breath testing, stool antigen detection, or endoscopy with biopsy specimens that allows for microscopic examination, urease detection, and culture. In a recent report of upper GI endoscopic findings in the cART era, H. pylori infections were identified in 40% of endoscopic biopsies and were more frequent than during the pre-ART era (11%) [11]. The two main indications for performing an endoscopy were abdominal discomfort (31%), and reflux symptoms (16%). The clinical presentation and treatment options for H. pylori infection do not differ from those for HIV-uninfected patients [21]. However, careful attention must be paid when choosing treatment regimens because of potential drug–drug interactions (DDIs) between proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and certain antiretrovirals, mostly the protease inhibitor (PI) atazanavir (see Table 18.1).

Table 18.1 Preferred and alternative initial therapies of Helicobacter pylori infection,a treatment duration, eradication rate, and potential for drug–drug interactions (DDIs) with ART

Upper GI illnesses in patients with HIV-related immunodeficiency may be caused by opportunistic infections or neoplasms. CMV may cause erosive gastritis with or without aphthous ulcerations, and solitary superficial and deep ulcerations that may be associated with esophageal involvement [25]. Since CMV usually arises in deeply immunosuppressed patients (CD4 T cell count < 50 cells/mm3), concomitant opportunistic pathogens such as Candida species and HSV may be present. Other rare gastric infections that have been reported in HIV-infected patients include cryptosporidiosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, leishmaniasis, toxoplasmosis, syphilis, bacillary angiomatosis, schistosomiasis, and strongyloidosis. The incidence of KS and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), two of the three AIDS-defining malignancies, has declined significantly in the post-cART era [26]. KS, caused by HHV-8, may affect any part of the GI tract with or without concurrent mucocutaneous involvement. Gastric KS is rarely symptomatic but can present with abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and dyspepsia. Rare severe complications such as bleeding and perforation can occur [27]. At endoscopy, KS typically appears as red or purple, small submucosal vascular nodules without ulceration. The mainstay of treatment in patients with HIV is cART for restoring immunity. Additional treatment options include local treatment for bleeding lesions and systemic chemotherapy. The stomach is the more common site of gastrointestinal NHL. Diagnosis and treatment are similar to those for HIV-uninfected patients.

Diarrhea

Since the beginning of the HIV epidemic, chronic diarrhea has been one of the signature manifestations of advanced HIV infection and AIDS. In developing countries, diarrhea is often due to opportunistic infections in patients with decreased immunity and remains a major cause of malnutrition, wasting syndrome, and mortality [28, 29]. In developed countries in which patients have wide access to cART and therefore live longer, the incidence of opportunistic infections is less, although the incidence of chronic diarrhea has remained stable, reflecting a change in underlying causes [30]. In these patients with a partially reconstituted immune system due to cART, diarrhea is still a common complaint and can lead to significant discomfort. ART (mostly PI)-associated diarrhea, and causes of diarrhea seen in HIV-uninfected patients, including Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, are predominant in this patient population [31, 32].

Diarrhea can be acute or chronic. Acute diarrhea is defined as the occurrence of at least three loose or watery stools daily for 3 days and up to 2 weeks. Chronic diarrhea is diagnosed when symptoms have been present for more than 4 weeks [33]. When evaluating a patient with acute or chronic diarrhea, a careful history is essential to help prioritize the differential diagnosis and decide on pertinent diagnostic studies to request. Key elements of the history of diarrhea in HIV-infected patients include the most recent CD4 T cell count, past history of opportunistic infections, past history of diarrheal illnesses, practice of unsafe sex, recent and present antibiotic use, HIV regimen, and adherence to treatment. All other pertinent elements of the questionnaire of patients with diarrhea should also be obtained. Characterization of the diarrhea (volume, duration, frequency) and associated symptoms (nausea, abdominal cramps, bleeding, weight loss, fever, and others) can be helpful for attempting to differentiate small- versus large-bowel disease, but symptoms can easily overlap. Upper abdominal cramping and bloating suggest small-bowel involvement or enteritis; hematochezia, tenesmus, and lower abdominal cramping suggest colonic involvement (see below). Patients with CD4 T cell counts > 200 cells/mm3 are likely to be diagnosed with diseases similar to those of HIV-uninfected patients unless ART-induced diarrhea is the likely diagnosis. PIs are the ART class most likely to cause diarrhea. The inevitable use of ritonavir for PI boosting contributes to this risk. The two preferred PIs as initial HIV therapy in 2011 according to the DHHS guidelines [34], atazanavir/ritonavir and darunavir/ritonavir, have been reported to cause diarrhea in 3 and 4%, respectively, compared to 10–11% for lopinavir/ritonavir and 13% for fosamprenavir/ritonavir after 1 year of treatment in previously naïve-to-ART patients [35–37]. Causes of diarrhea other than opportunistic infections should also be considered in HIV-infected patients and diagnosed with conventional tests. The most frequent pathogens causing non-opportunistic infectious diarrhea in HIV-infected patients are the bacteria Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yersinia, Vibrio, E. coli, C. difficile, and others; the viruses rotavirus, Norwalk, and adenovirus; and the parasites Giardia, Entamoeba, and Blastocystis. Antibiograms of isolated bacteria are helpful since resistance to commonly used antibiotics has been described [38]. Salmonellosis, although not considered an opportunistic infection, is about 100 times more frequent in HIV patients than in immunocompetent hosts [39]. Recurrent Salmonella bacteremia in an HIV patient establishes a diagnosis of AIDS. Celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, ischemic colitis, appendicitis, and others must also be considered, depending on the clinical presentation.

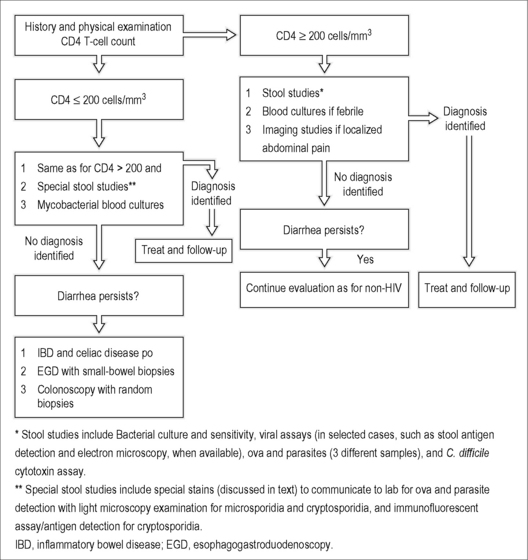

The degree of immunosuppression, represented by the CD4 T cell count, is one of—if not—the most useful pieces of information when evaluating such patients. Those with CD4 T cell counts < 200 cells/mm3, but mostly those with CD4 T cell counts < 100 cells/mm3, are more likely to be diagnosed with opportunistic infections and special diagnostic studies should be undertaken. See Figure 18.2 for a suggested approach to the HIV-infected patient with diarrhea. In patients with severe immunodeficiency (CD4 T cell < 100 cells/mm3), opportunistic pathogens, such as cryptosporidia (Cryptosporidium parvum, C. hominis, and others), microsporidia (Enterocytozoon bieneusi, Encephalitozoon intestinalis, and others), CMV, and mycobacteria (Mycobacterium avium complex [MAC] and M. tuberculosis) are expected, alone or in combination, and should be ruled out carefully [40, 41]. Studies performed in men who have sex with men (MSM) with AIDS and diarrhea before cART became available identified one or more enteric pathogens in 68–85% of patients [42, 43]. Cryptosporidiosis is diagnosed by microscopic examination of stool samples. It should be specifically requested when stool samples are sent to the laboratory since they can easily be missed during routine stool examinations. Acid-fast staining methods (usually the modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain) can be used. They allow differentiation of the small Cryptosporidium oocysts (which stain pink or red) from yeasts and stool debris (which stain green or blue). Immunofluorescent assays and antigen-detection assays are also available. Cryptosporidium can also be detected with hematoxylin and eosin staining of small intestinal biopsies. Microsporidia can be found in stool samples when special staining methods such as modified trichrome stain (chromotrope 2R) and calcofluor white are used. Small intestinal biopsies stained with these two techniques, Giemsa, hematoxylin and eosin, and other methods can make the diagnosis. Electron microscopy is used to identify microsporidia at the species level. The two other protozoa, Isospora belli and Cyclospora cayetanensis, can be detected with the modified Ziehl–Neelsen stain (which appears red) and both are autofluorescent blue under ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy. When stool samples are repeatedly negative and diarrhea persists, upper endoscopy and colonoscopy with random biopsies of small intestine and colon are recommended. The yield of upper endoscopy in HIV patients with chronic diarrhea is between 11 and 36%, with cryptosporidia and microsporidia being the most frequently identified pathogens [44]. For colonoscopy, the yield is 27–42%, with CMV being the most common diagnosis [44]. MAC can infect the small bowel of severely immunosuppressed patients (usually with CD4 count < 50 cells/mm3) and results in disseminated disease. Patients can present with malabsorptive diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Mycobacterial blood cultures are helpful for diagnosing disseminated disease. Blood cultures are positive in approximately 90% of patients with disseminated disease and were as high as 99% when two specimens were taken in one study [45]. Endoscopy with small-bowel biopsy and acid-fast staining can identify MAC, which can also grow in appropriate media.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree