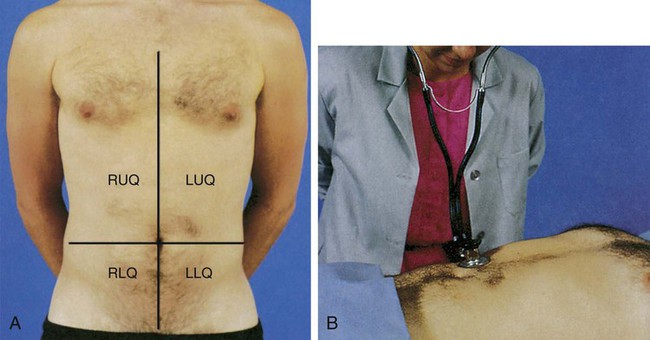

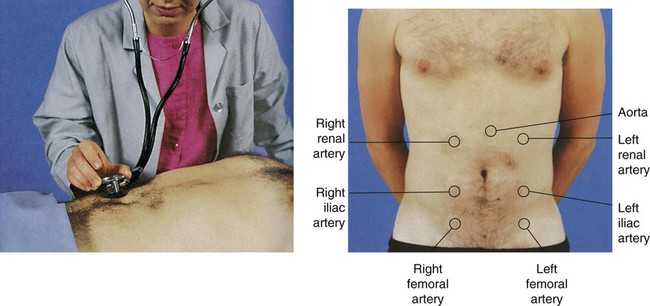

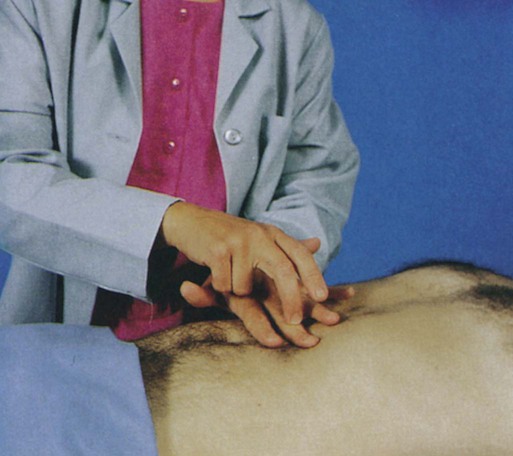

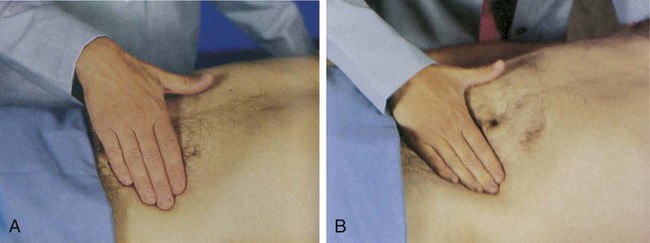

Chapter 29 A thorough clinical assessment of the patient with GI dysfunction is imperative for the early identification and treatment of GI disorders. The completed assessment serves as the foundation for developing the management plan for the patient. The assessment process can be brief or can involve a detailed history and examination, depending on the nature and immediacy of the patient’s situation.1,2 The initial presentation of the patient determines the rapidity and direction of the interview. For a patient in acute distress, the history should be curtailed to a few questions about the patient’s chief complaint and the precipitating events. For a patient in no obvious distress, the history should focus on current symptoms, the patient’s medical history, and the family’s history. Specific items regarding each of these areas are outlined in Box 29-1, Data Collection.3,4 The physical examination helps establish baseline data about the physical dimensions of the patient’s situation.3 The abdomen is divided into four quadrants (left upper, right upper, left lower, and right lower), with the umbilicus as the middle point, to specify the location of examination findings (Fig. 29-1 and Box 29-2). The assessment should proceed when the patient is as comfortable as possible and in the supine position; however, the position may need readjustment if it elicits pain. To prevent stimulation of GI activity, the order for the assessment should be changed to inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation.4 Observe the skin for pigmentation, lesions, striae, scars, petechiae, signs of dehydration, and venous pattern. Pigmentation may vary considerably and still be within normal limits because of race and ethnic background, although the abdomen usually is of a lighter color than other exposed areas of the skin. Abnormal findings include jaundice, skin lesions, and a tense and glistening appearance of the skin. Old striae (stretch marks) usually are silver, whereas pinkish purple striae may indicate Cushing syndrome.4 A bluish discoloration of the umbilicus (Cullen sign) and of the flank (Grey-Turner sign) indicates retroperitoneal bleeding.1 Observe the abdomen for contour, noting whether it is flat, slightly concave, or slightly round; observe for symmetry and for movement. Marked distention is an abnormal finding. In particular, ascites may cause generalized distention and bulging flanks. Asymmetric distention may indicate organ enlargement or a mass. Peristaltic waves should not be visible except in very thin patients. In the case of intestinal obstruction, hyperactive peristaltic waves may be observed. Pulsation in the epigastric area is often a normal finding, but increased pulsation may indicate an aortic aneurysm. Symmetric movement of the abdomen with respirations is usually seen in men.4,5 Auscultation of the abdomen provides clinical data regarding the status of the bowel’s motility. Initially, listen with the diaphragm of the stethoscope below and to the right of the umbilicus. The examination proceeds methodically through all four quadrants, lifting and then replacing the diaphragm of the stethoscope lightly against the abdomen (see Fig. 29-1). Normal bowel sounds include high-pitched, gurgling sounds that occur approximately every 5 to 15 seconds or at a rate of 5 to 34 times per minute. Colonic sounds are low pitched and have a rumbling quality. A venous hum may be audible sometimes.6 Table 29-1 provides a list of abnormal abdominal sounds. TABLE 29-1 LUQ, Left upper quadrant; RUQ, right upper quadrant. From Doughty DB, Jackson DB. Gastrointestinal Disorders. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993. Abnormal findings include the absence of bowel sounds throughout a 5-minute period, extremely soft and widely separated sounds, and increased sounds with a high-pitched, loud rushing sound (peristaltic rush). Absent bowel sounds may result from inflammation, ileus, electrolyte disturbances, and ischemia. Bowels sounds may be increased with diarrhea and early intestinal obstruction.6 The abdomen should be auscultated for the presence of bruits, using the bell of the stethoscope (Fig. 29-2). Bruits are created by turbulent flow over a partially obstructed artery and are always considered an abnormal finding. The aorta, the right and left renal arteries, and the iliac arteries should be auscultated.5,6 Percussion is used to elicit information about deep organs such as the liver, spleen, and pancreas (Fig. 29-3). Because the abdomen is a sensitive area, muscle tension may interfere with this part of the assessment. Percussion often helps relax tense muscles, and it is performed before palpation. Percussion in the absence of disease helps delineate the position and size of the liver and spleen, and it assists in the detection of fluid, gaseous distention, and masses in the abdomen.5 Percussion should proceed systematically and lightly in all four quadrants. Normal findings include tympany over the empty stomach, tympany or hyper-resonance over the intestine, and dullness over the liver and spleen. Abnormal areas of dullness may indicate an underlying mass. Solid masses, enlarged organs, and a distended bladder also produce areas of dullness. Dullness over both flanks may indicate ascites and necessitates further assessment.6 Palpation is the assessment technique most useful in detecting abdominal pathologic conditions. Light and deep palpation of each organ and quadrant should be completed. Light palpation, which has a palpation depth of approximately 1 cm, assesses to the depth of the skin and fascia (Fig. 29-4A). Deep palpation assesses the rectus abdominis muscle and is performed bimanually to a depth of 4 to 5 cm (see Fig. 29-4B). Deep palpation is most helpful in detecting abdominal masses. Areas in which the patient complains of tenderness should be palpated last.6 Normal findings include no areas of tenderness or pain, no masses, and no hardened areas. Persistent involuntary guarding may indicate peritoneal inflammation, particularly if it continues even after relaxation techniques are used. Rebound tenderness, in which pain increases with quick release of a palpated area, indicates an inflamed peritoneum.4 Table 29-2 presents a variety of common GI disorders and their associated assessment findings. TABLE 29-2 ASSESSMENT FINDINGS OF COMMON GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS

Gastrointestinal Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures

Clinical Assessment

History

Physical Examination

Inspection

Auscultation

SOUND

CAUSE

Hyperactive bowel sounds (borborygmi), loud and prolonged

Hunger, gastroenteritis, or early intestinal obstruction

High-pitched, tinkling sounds

Intestinal air and fluid under pressure; characteristic of early intestinal obstruction

Decreased (hypoactive) bowel sounds

Possible peritonitis or ileus

Infrequent and abnormally faint sounds

Absence of bowel sounds (confirmed only after auscultation of all four quadrants and continuous auscultation for 5 minutes)

Temporary loss of intestinal motility, as occurs with complete ileus

Friction rubs

Pathologic conditions such as tumors or infection that cause inflammation of organ’s peritoneal covering

High-pitched sounds heard over liver and spleen (RUQ and LUQ), synchronous with respiration

Bruits

Abnormality of blood flow (requires additional evaluation to determine specific disorder)

Audible swishing sounds that may be heard over aortic, iliac, renal, and femoral arteries

Venous hum

Increased collateral circulation between portal and systemic venous systems

Low-pitched, continuous sound

Percussion

Palpation

Assessment Findings for Common Disorders

CONDITION

HISTORY

SYMPTOMS

SIGNS

Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ) of the Abdomen

Appendicitis

Children (except infants) and young adults

Anorexia

Signs may be absent early

Nausea

Vomiting

Early vague epigastric, periumbilical, or generalized pain after 12-24 hours; RLQ at McBurney point

Localized RLQ guarding and tenderness after 12-24 hours

Rovsing sign: pain in RLQ with application of pressure, iliopsoas sign

Obturator sign

White blood cell count of 10,000/mm3 or shift to left

Low-grade fever

Cutaneous hyperesthesia in RLQ

Signs highly variable

Perforated duodenal ulcer

Prior history

Abrupt onset pain in epigastric area or RLQ

Tenderness in epigastric area or RLQ

Signs of peritoneal irritation

Heme-positive stool

Increased white blood cell count

Cecal volvulus

Seen most often in older adults

Abrupt severe abdominal pain

Distention

Localized tenderness

Tympany

Strangulated hernia

Any age

Severe localized pain

If bowel obstructed, distention

Women: femoral

If bowel obstructed, generalized pain

Men: inguinal

Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ) of the Abdomen

Liver hepatitis

Any age, often young blood product user

Fatigue

Hepatic tenderness

Malaise

Hepatomegaly

Drug addict

Anorexia

Bilirubin elevated

Pain in RUQ

Jaundice

Low-grade fever

Lymphocytosis in one third of cases

May have severe fulminating disease with liver failure

Liver enzymes elevated

Hepatitis A or B or antibodies to the viruses may be found

Acute hepatic congestion

Usually older adults with acute heart failure

Symptoms of acute heart failure

Hepatomegaly

Pericardial disease

Acute heart failure

Pulmonary embolism

Biliary stones, colic

“Fair, fat, forty” (90%) but can be 30 to 80 years old

Anorexia

Nausea

Tenderness in RUQ

Jaundice

Pain severe in RUQ or epigastric area

Episodes lasting 15 minutes to hours

Acute cholecystitis

“Fair, fat, forty” (90%) but may be 30 to 80 years old

Severe RUQ or epigastric pain

Vomiting

Episodes prolonged up to 6 hours

Tenderness in RUQ

Peritoneal irritation signs

Increased white blood cell count

Perforated peptic ulcer

Any age

Abrupt RUQ pain

Tenderness in epigastrium, right quadrant, or both

Peritoneal irritation signs

Free air in abdomen

Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ) of the Abdomen

Splenic trauma

Blunt trauma to LUQ of abdomen

Pain: LUQ pain of the abdomen often referred to the left shoulder (Kehr sign)

Hypotension

Syncope

Increased dyspnea

Radiographic studies show enlarged spleen

Pancreatitis

Alcohol abuse

Pain in LUQ or epigastric region radiating to the back or chest

Fever

Pancreatic duct obstruction

Rigidity

Rebound tenderness

Infection

Nausea

Cholecystitis

Vomiting

Jaundice

Cullen sign

Turner sign

Abdominal distention

Diminished bowel sounds

Pyloric obstruction

Duodenal ulcer

Weight loss

Increasing dullness in LUQ

Gastric upset

Visible peristaltic waves in epigastric region

Vomiting

Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ) of the Abdomen

Ulcerative colitis

Family history

Chronic, watery diarrhea with bloody mucus

Fever

Jewish ancestry

Cachexia

Anorexia

Anemia

Weight loss

Leukocytosis

Fatigue

Colonic diverticulitis

Older than 39 years

Pain that recurs in LUQ

Fever

Low-residue diet

Vomiting

Chills

Diarrhea

Tenderness over descending colon ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Gastrointestinal Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Procedures

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access