G

Gastritis

Description

Gastritis, an inflammation of the gastric mucosa, is one of the most common problems affecting the stomach. Gastritis may be acute or chronic and diffuse or localized.

Pathophysiology

Gastritis occurs as the result of a breakdown in the normal gastric mucosal barrier. This mucosal barrier normally protects the stomach tissue from the corrosive action of HCl acid and pepsin. When the barrier is broken, HCl acid and pepsin can diffuse back into the mucosa. This back diffusion results in tissue edema, disruption of capillary walls with plasma lost into the gastric lumen, and possible hemorrhage.

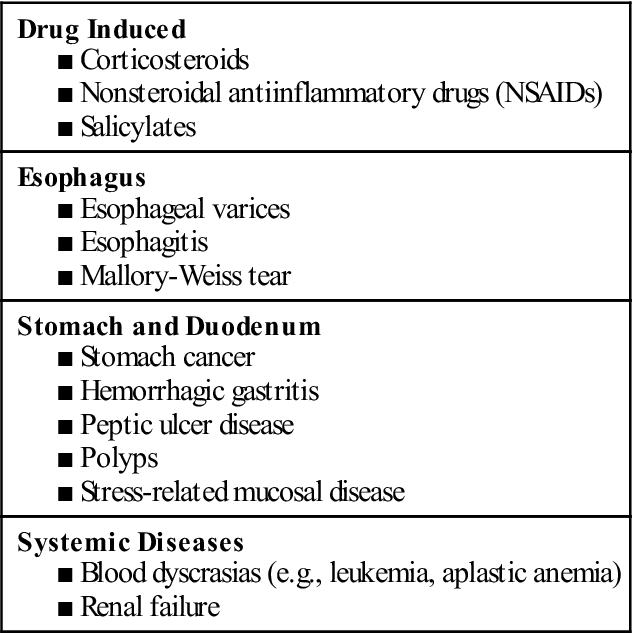

Drugs contribute to the development of acute and chronic gastritis. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, and corticosteroids inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins that are protective to the gastric mucosa, making the mucosa more susceptible to injury. Risk factors for NSAID-induced gastritis include being female; being over age 60; having a history of ulcer disease; taking anticoagulants, other NSAIDs (including low-dose aspirin), or other ulcerogenic drugs (including corticosteroids); and having a chronic debilitating disorder such as cardiovascular disease.

Repeated alcohol abuse results in chronic gastritis. Eating large quantities of spicy, irritating foods and metabolic conditions such as renal failure can also cause acute gastritis.

Another cause of chronic gastritis is Helicobacter pylori infection, which is highest in underdeveloped countries and in people of low socioeconomic status.

Autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (also called autoimmune atrophic gastritis) is an inherited condition in which there is an immune response directed against parietal cells. Atrophic gastritis is associated with an increased risk of stomach cancer.

Clinical manifestations

Diagnostic studies

Diagnosis of acute gastritis is most often based on a history of drug and alcohol use.

Collaborative care

Treatment of acute gastritis focuses on eliminating the cause and preventing or avoiding it in the future. The plan of care is supportive and similar to that described for nausea and vomiting.

Treatment of chronic gastritis focuses on evaluating and eliminating the specific cause.

■ Currently antibiotic combinations are used to eradicate infection with H. pylori.

■ For the patient with pernicious anemia, lifelong administration of cobalamin is needed.

The patient undergoing treatment for chronic gastritis may have to adapt to lifestyle changes and strictly adhere to a drug regimen. An interdisciplinary team approach in which the physician, nurse, dietitian, and pharmacist provide consistent information and support may increase patient success in making these alterations.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

Description

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) results from mucosal damage caused by reflux of stomach acid into the lower esophagus. GERD is not a disease but a syndrome. GERD is the most common upper GI problem. Approximately 10% to 20% of the U.S. population experience GERD symptoms (heartburn or regurgitation) at least once a week.

Pathophysiology

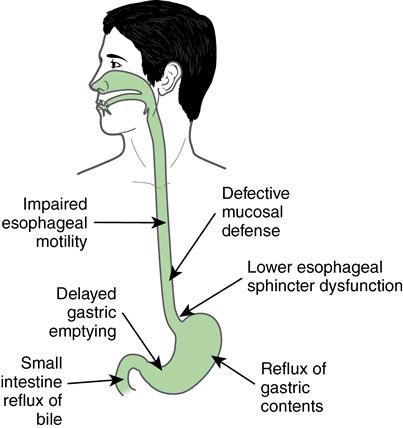

GERD has no one single cause (Fig. 6). GERD results when the defenses of the esophagus are overwhelmed by the reflux of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus. One of the primary etiologic factors in GERD is an incompetent lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Under normal conditions, the LES acts as an antireflux barrier. An incompetent LES lets gastric contents move from the stomach to the esophagus when the patient is supine or has an increase in intraabdominal pressure.

Gastric HCl acid and pepsin secretions that reflux cause esophageal irritation and inflammation (esophagitis). The degree of inflammation depends on the amount and composition of the gastric reflux and on the esophagus’s mucosal defense mechanisms.

Clinical manifestations

Symptoms vary from person to person, with symptoms that persistently occur more than twice a week generally indicative of GERD.

Complications

Complications are related to the effects of gastric acid secretion on the esophageal mucosa. Esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus) is a common complication of GERD. Repeated esophagitis may cause scar tissue formation, stricture, and ultimately dysphagia. Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous lesion, increases the patient’s risk for esophageal cancer.

Diagnostic studies

Diagnostic studies help determine the cause of the GERD.

Collaborative care

Most patients with GERD can successfully manage this condition through lifestyle modifications and drug therapy. These long-term approaches require patient teaching and adherence to therapies.

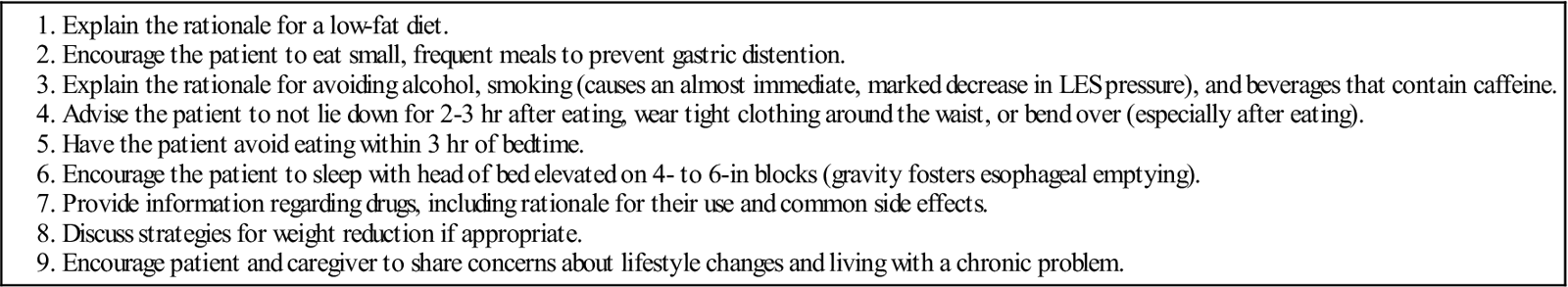

Teach the patient to avoid factors that trigger symptoms. Give particular attention to diet and other medications that may affect the LES, acid secretion, or gastric emptying. Encourage patients who smoke to stop.

Food can aggravate symptoms. No specific diet is necessary. Teach patients to avoid foods such as chocolate, peppermint, tomatoes, fatty foods, coffee, and tea that decrease LES pressure and predispose them to reflux. Small, frequent meals help prevent overdistention of the stomach. Late evening meals and nocturnal snacking should be avoided. Weight reduction is recommended if the patient is obese.

Drug therapy

Drug therapy focuses on improving LES function, increasing esophageal clearance, decreasing volume and acidity of reflux, and protecting esophageal mucosa. Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2-receptor blockers are effective treatments for symptomatic GERD. The goal of HCl acid suppression treatment is to reduce the acidity of the gastric refluxate. Patients who are symptomatic with GERD but do not have evidence of esophagitis achieve symptom relief with PPI and H2-receptor agents. The PPIs are more effective in healing esophagitis than are H2-receptor blockers.

Antacids with or without alginic acid (e.g., Gaviscon) may be useful in patients with mild, intermittent heartburn.

Surgical therapy

Surgical therapy is reserved for patients with complications of reflux, including esophagitis, intolerance of medications, stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and persistence of severe symptoms. Most surgical procedures are performed laparoscopically. The goal of surgery is to reduce reflux by enhancing the integrity of the LES. In these procedures the fundus of the stomach is wrapped around the lower portion of the esophagus to reinforce and repair the defective barrier.

Alternatives to surgical therapy include endoscopic mucosal resection, photodynamic therapy, cryotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation (image-guided technique that kills cells through heating).

Nursing management

Nursing care for the patient with acute symptoms consists of encouraging the patient to follow the necessary regimen (Table 38).

Table 38

Patient and Caregiver Teaching Guide

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Postoperative care focuses on prevention of respiratory complications, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, and prevention of infection. Laparoscopic procedures reduce the risk of respiratory complications. During the postoperative phase, patients require medications to prevent nausea and vomiting and to control pain.

Gastrointestinal bleeding, upper

Description

In the United States approximately 300,000 hospital admissions occur each year for upper GI bleeding. Approximately 60% of these are adults over age 65. Despite advances in the drug management of predisposing conditions and identification of risk factors, the mortality rate for upper GI bleeding has remained at approximately 6% to 13% for the past 45 years.

Pathophysiology

Although the most serious loss of blood from the upper GI tract is characterized by a sudden onset, insidious occult bleeding can also be a major problem. Bleeding severity depends on whether the origin is venous, capillary, or arterial. Bleeding from an arterial source is profuse, and the blood is bright red. In contrast, “coffee ground” vomitus indicates that the blood has been in the stomach for some time. Melena (black, tarry stools) indicates slow bleeding from an upper GI source.

A variety of areas in the GI tract may be involved. Table 39 lists common causes of upper GI bleeding. The most common sites are the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum.

Table 39

Common Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Complications

Although approximately 80% to 85% of patients who have massive hemorrhage spontaneously stop bleeding, the cause must be identified and treatment initiated immediately.

To facilitate early intervention, the physical examination should focus on early identification of signs and symptoms of shock such as tachycardia, weak pulse, hypotension, cool extremities, prolonged capillary refill, and apprehension. Monitor vital signs every 15 to 30 minutes. The patient is at risk for gut perforation and peritonitis, which may be indicated by a tense, rigid, boardlike abdomen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree