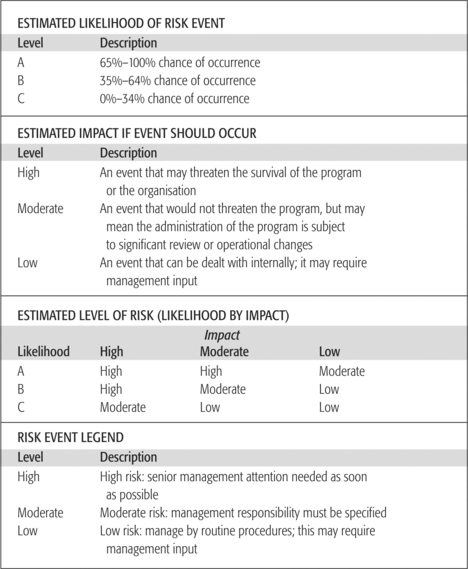

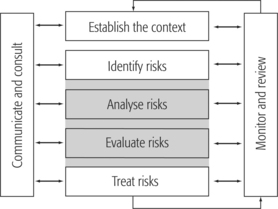

CHAPTER 17 From risk management to clinical governance The advances made in other industries and sectors — such as aviation and the chemical industry — have shown that a safety culture does make a difference. Major reports on the level of adverse events in health in the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom have forced a rethink of attitudes and approaches to risk and risk management in health. In common parlance we refer to risk as the chance of injury, damage or loss. We usually think of risk in the narrow context of domestic insurance and litigation. The Australian Standard on Risk Management (Standards Australia 1999, p 3) and the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) (2001a, p 35) define risk as ‘The chance of something happening that will have an impact upon objectives. It is measured in terms of consequences and likelihood.’ Kunreuther and Slovic (1996) point out that risk involves value judgments that reflect much more than the probability and consequences of the occurrence of an event. In this view the way in which risks are expressed and how they are perceived by the public, the institutional, procedural and societal processes in risk management decisions are indicators of the need for a new approach to risk assessment. They draw particular attention to the problem of the different perceptions of technical experts and the public. This issue has been well illustrated in the early assessment of risk in the outbreak of BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), which has now caused over 80 deaths in the United Kingdom alone (Box 17.1). BOX 17.1 KEY EVENTS IN THE ASSESSMENT OF RISK IN THE OUTBREAK OF BOVINE SPONGIFORM ENCEPHALOPATHY (BSE) IN THE UNITED KINGDOM* The repercussions from the BSE outbreak and the response of governments will continue for years to come. Press comment throughout the inquiry, and since, has been savage. Neither government ministers nor government heads of departments have been spared. This case study will be considered further because it would be hard to find a better example of systemic failure to take an organised approach to identifying, analysing and dealing with a risk shrouded in uncertainty. Key points from the official BSE inquiry released in October 2000 by Lord Phillips are outlined in Box 17.2. BOX 17.2 KEY POINTS FROM THE OFFICIAL BSE INQUIRY RELEASED IN OCTOBER 2000 BY LORD PHILLIPS Source: Assessment of risk in the outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in the UK 2000. Online. Available: www.bseinquiry.gov.uk/report/volume1/execsum.htm The issue of differing perceptions of risk and subsequent response has also been well illustrated in numerous highly publicised ‘health system failures’. As an example, the MacArthur Health Service Investigation Report (Health Care Complaints Commission December 2003, http://www.archi.net.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/168475/fromItemId/117303) identified problems with quality and safety systems that included: Failure to recognise and respond to risks emerged as the predominant area of vulnerability of the MacArthur Health Service. Similarly the King Edward Memorial Hospital Inquiry (1990–2000, http://www.slp.wa.gov.au/publications/publications.nsf/Inquiries+and+Commissions) found significant leadership, management and clinical performance problems including: It was only in 1980 that the American Healthcare Association (AHA) (1997) formed a national group dedicated to risk management. This was mainly as a result of the growth in medical negligence litigation in the 1970s. In Britain, the National Health Service (NHS) published ‘Risk Management in the NHS’ in October 1993; this was followed by the establishment of the Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts in 1995 and the NHS Litigation Authority in 1996. The current emphasis in the United Kingdom is on clinical activity in a rich mixture of clinical governance structures and reports such as ‘Building a safer NHS for patients. Implementing an organisation with a memory’ (doh.gov.uk). In Australia, the publication of the findings of the Quality of Australian Health Care Study (Wilson et al 1995) gave impetus to risk management initiatives. This study reported an adverse event rate of 16.6 per cent associated with hospital admissions and 51 percent of these were considered preventable. ‘Reanalysis using US methodology suggests that at least 10 per cent of acute hospital admissions were associated with a potentially preventable adverse event’ (Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care 2004, p 69). The Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care reported (2004, p 69) that a follow-up comparison of the Australian study and an American study of adverse events in Utah and Colorado, found that the level of serious adverse events was almost identical between the studies. In both studies 0.3 per cent of admissions were associated with an iatrogenic death and 1.7 per cent associated with iatrogenic disability. Understandably, the level of adverse events reported in 1995 by Wilson et al raised serious concern and in January 2000 the Australian Health Ministers established the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) to implement the findings of the National Expert Advisory Group chaired by Professor Robert Porter. The aim of the council is to ‘lead to national efforts to improve the safety and quality of health care, with a particular focus on minimising the likelihood and effects of error’ (ACSQHC 2001b, p 31). In the same year the minister announced the establishment of the National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS) under the chairmanship of the late Professor Chris Silagy and more recently Professor Chris Baggoley. Some other Australian initiatives include the publication by the New South Wales Department of Health (1999) of A Framework for Managing the Quality of Health Services in New South Wales, which specifically leads towards an organised structure of clinical governance. It is significant that Standards Australia (2001) has now published Guidelines for Managing Risk in Health Care (HB 228) to recognise the special issues to be resolved to improve outcomes in health care. The Australian Institute of Risk Management (1997, p 3) has defined risk management as ‘the application of resources to the likelihood of unwanted, negative consequences of an action or set of circumstances’. Similarly, the Australian Council for Safety and Quality in Health Care (2001a, p 35) defines risk management as ‘the culture, processes and structures that are directed towards effective management of risk’. It is significant therefore that the introduction to the Australian Standards (Standards Australia 1999) makes it clear that: Figure 17.1 shows the connections between the major components of risk management (Standards Australia 2001, p 20). According to this diagram, the context needs to be established, then the risks identified, analysed and evaluated and then treated. This is depicted as an ongoing process of monitoring and reviewing, which requires effective consultation and communication with all stakeholders. FIGURE 17.1 Risk management overview Source: Standards Australia 1999 AS/NZS 4360:1999 Australian Standard Risk Management. Standards Association of Australia, Strathfield, NSW, p 8 Figure 17.2 shows how identified risks might be grouped according to defined priorities for action based on an estimation of the likelihood of the risk occurring and the resulting impact if it should occur. In the BSE example (Boxes 17.1 and 17.2) it is instructive to identify context from material. Closer examination of the case (see www.bseinquiry.gov.uk/report/volume1/execsum.htm) indicates that each participant perceived the situation differently and this influenced their analysis and account of the risk. No doubt the scientists, bureaucrats, politicians and advisers took different stances on risk to the beef industry, European trade, and animal and human health in the United Kingdom and abroad. Depending on their official position and personal values they would also have to take into account time frames, uncertainty, particularly as to the scientific evidence, and the various forms risk manifested in each situation. It is also clear that the events and outcomes had different levels of probability and that a good deal of wishful thinking influenced behaviour. As the press comments suggest, the case was handled according to the established culture in the political bureaucracy in the United Kingdom at the time. This reinforces the importance of the identification of institutional, procedural and societal processes in risk management. Students of management are familiar with the changing fashions in modern management theories which have informed academics and practitioners alike for the past century or more (see Shafritz & Ott 1996, and Chapters 2 and 4 of this book). One way of looking at the various dominant notions is to distinguish between theories and advised practices which focus largely on internal operations, such as task/workflow analysis and human relations, as opposed to external influences, such as competition policy and decentralisation. These trends can be considered along with such advised techniques for management as project and strategic planning and more recently total quality management (TQM) and continuous quality improvement (CQI). Is risk management one of these techniques or something more significant? There is increasing recognition of the need to improve patient safety and service quality, at the same time as improving productivity and cost effectiveness. Improvements involve change to individual behaviour, the systems and organisation of care. Four of the main obstacles to quality improvement have been identified as time, territory, tradition and trust (Berwick et al 1992). The latter three elements in particular are reflected in the specific culture of the health system. A special edition of the British Medical Journal (BMJ) in March 2000 (Leape & Berwick 2000) identified the need for a change from the culture of blame to one of learning, trust, curiosity, systems thinking and executive responsibility. James Reason (2000, p 768), in the same series of articles, commented on the Chernobyl disaster ‘Trust is a key element of a reporting culture and this, in turn, requires the existence of a just culture… engineering a just culture is an essential early step in creating a safe culture’. How then is a manager to maintain trust at the very time that providers of care are most suspicious of the aims of management programs for cost reduction, contracting out and perceived intrusions into clinical activity through new funding methods, including casemix and contracts with insurers? The gap between managers and health professionals is another feature of the health system and one often underestimated by policy makers. A recent study has shown what practising managers already knew: that health care professionals and managers live in different worlds (Cochrane 1999). The research finding was that clinicians did not feel that either organisational factors or managerial involvement were helpful in changing practice and improving patient care. These differences in attitude between clinicians and managers are a serious obstacle to effective action. What is clear at the service provider level is that a high degree of trust is an essential condition of competent, quality service provision and effective institutional performance. It is part of institutional culture. Risk management links conveniently with the rediscovered school of management thought of the ‘learning organisation’. The essence of this school of thought is that managers have to actively learn from experience to deal with the permanent turbulence in the environment. Managers and all staff have to be able to see organisations as systems, take control of situations, adapt and learn to reframe the problems. Adaptation strategies; that is, doing what worked last time, is not enough, because too many other things are going on and changing at the same time. Dealing with turbulence involves an active assessment of the opportunities and risks in the situation (Argyris & Schön 1978, Bloor 1999, Garside 1999, Handy 1989, Revans 1976, 1982). So because the profession is largely self-controlling it relies heavily on the personal responsibility assumed by professionals when taking on the care of a patient. At the same time doctors have to be accountable before the civil and criminal law and more recently to a variety of administrative and legal agencies, ranging from the ombudsman to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC 1999). Whether the medical colleges, medical boards and educational bodies carry out their duties to the satisfaction of society has not been seriously questioned until recently in Australia. Recent events in the United States and the United Kingdom have accelerated the rate of change in attitudes in Australia. Increased litigation, medical disasters, consumer sovereignty and social change in general have influenced governments and the public to adopt a much more critical view of the performance of the medical profession. A series of deaths following heart surgery in Bristol and the subsequent inquiry conducted by Professor Ian Kennedy have raised the level of concern about medical error and incompetence to a new high. (For information about the Bristol case, see www.bristol-inquiry.org.uk) Donald Irvine, President of the General Medical Council (GMC) in Britain, maintained that it was essential for the public to rediscover trust in the medical profession, and made the case for a new agreement between medicine and society. Professional self-regulation is a privilege and not a right and cannot be assured without competent self-regulation, which meant a system of explicit criteria and standards requiring hard evidence of compliance (Irvine 1997a, 1997b, 1999). This is an issue under scrutiny in much of the English-speaking world. Newble et al (1999) have described the situation in Australasia and go further in calling for the direct assessment of patient care. The traditional doctor–patient relationship is viewed by some authors as ‘professional paternalism’ (Sharpe & Faden 1998, p 67). Social conditions and the influence of ideas from Europe and America have sharply affected attitudes in Australia. Patient autonomy has been recognised here in a number of important legal cases, and this has changed the power relationship between doctor and patient; for example, see Rogers v Whittaker (1992) 109 Australian Law Reports 625–37 and Office of Safety and Quality in Health Care (2005). It has also changed our view of the meaning of consent and professional responsibility, including that for maintaining efficient systems of records. Recent Australian case law defines performance standards more clearly, including omissions, especially in providing enough information on risks. In so doing the courts have established that the standard of care is a matter to be decided by the courts and not medical opinion. This signifies an important shift from ‘professional paternalism’ to a community standard. Sharpe and Faden (1998, p 67) (talking about the United States) put it thus:

INTRODUCTION

RISK DEFINED

November 1986: BSE is officially recognised as a disease at the Ministry of Food and Fisheries. The Health Chief Medical Officer was not told at that time.

November 1986: BSE is officially recognised as a disease at the Ministry of Food and Fisheries. The Health Chief Medical Officer was not told at that time.

June 1987: the Chief Veterinary Officer tells his Minister about the disease. A year later BSE was made a notifiable disease and sheep offal was banned from cattle feed.

June 1987: the Chief Veterinary Officer tells his Minister about the disease. A year later BSE was made a notifiable disease and sheep offal was banned from cattle feed.

January 1990: the Agriculture Minister says ‘there is no evidence anywhere in the world of BSE passing from animals to humans’.

January 1990: the Agriculture Minister says ‘there is no evidence anywhere in the world of BSE passing from animals to humans’.

May 1995: the first human death from BSE occurs. It is designated as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).

May 1995: the first human death from BSE occurs. It is designated as variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).

March 1996: the Health Secretary says the most likely cause of ten deaths from vCJD was from eating BSE-infected products.

March 1996: the Health Secretary says the most likely cause of ten deaths from vCJD was from eating BSE-infected products.

failure by management to monitor and evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of any remedial action recommended; and

failure by management to monitor and evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of any remedial action recommended; and

non-existent ‘safety nets’ or systems to effectively monitor performance and respond to performance issues; and

non-existent ‘safety nets’ or systems to effectively monitor performance and respond to performance issues; and

failure to address serious and ongoing management and clinical problems that resulted in serious adverse events and poor outcomes for women and their families.

failure to address serious and ongoing management and clinical problems that resulted in serious adverse events and poor outcomes for women and their families.

THE EVOLUTION OF RISK MANAGEMENT

RISK MANAGEMENT DEFINED

THE PLACE OF RISK MANAGEMENT IN MANAGEMENT THEORY AND PRACTICE

Internal influences

Integrating the internal and external perspectives

CLINICAL ACTIVITY AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Health professionals and society

Health professionals and patients

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

From risk management to clinical governance

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access