Fluid Homeostasis

QUICK LOOK AT THE CHAPTER AHEAD

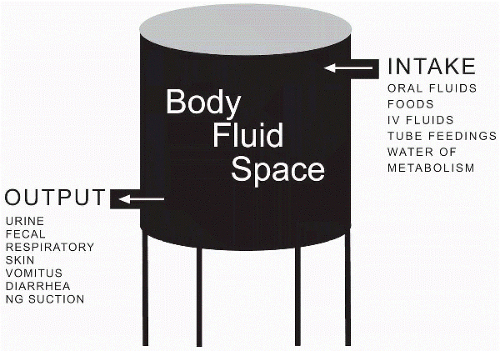

Daily fluid intake in the body should equal loss. In an effort to maintain fluid homeostasis fluids, nutrients, and waste products constantly shift among the body’s cells, vasculature, and interstitial area. In this chapter we examine the different ways of fluid intake and sites of fluid loss and explain the types of pressures that influence fluid secretion and reabsorption.

Body fluid has multiple functions, including maintaining body temperature, transporting oxygen and chemicals, and eliminating wastes. Maintaining homeostasis of fluid in the various compartments of the body involves balancing intake, absorption, distribution, and excretion.

Fluid Intake

Normal fluid intake involves drinking fluids orally and ingestion through food. Other methods of fluid intake include administration of water and liquid feedings through tubes inserted into the jejunum or gastric area. Intravenous fluids can be administered to those who need additional supplements to oral intake or who are unable to ingest or absorb fluids via the gastrointestinal tract. The body also has the ability to generate its own water through metabolism or oxidation of nutrients, such as carbohydrates and fat (Figure 7-1).

Absorption

An increased osmolality triggers the thirst center to initiate fluid intake. Once consumed, the fluid is then absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract before reaching the vascular compartment. If fluid is administered intravenously, then it is directly infused into the vascular compartment to help expand the extravascular or intravascular compartments.

An increased osmolality triggers the thirst center to initiate fluid intake.

An increased osmolality triggers the thirst center to initiate fluid intake.Fluid Distribution Between the Plasma and Interstitial Fluid

Once fluid has been absorbed into the vascular compartment, it is distributed through capillary filtration. Only the capillaries have the ability to allow the movement of fluids and solutes through their thin walls. This is accomplished through capillary hydrostatic pressure (pushing fluid out) and colloidal osmotic (oncotic) pressure (pulling fluid in). Capillary hydrostatic pressure is produced by the pumping action of the heart while the colloidal osmotic (oncotic) pressure is the force supplied by high-molecular-weight serum proteins, such as albumin, that are too large to escape through the capillary walls.

Because these forces work against each other, the flow of fluid depends on the strongest opposing force. When capillary hydrostatic (pushing) pressure exceeds the colloidal osmotic (oncotic) pressure (pulling fluid in), movement of fluids occurs from the intravascular to the interstitial area. This movement, capillary filtration, occurs at the arterial end of the capillary. At the venous end, capillary hydrostatic pressure is less than the colloidal osmotic (oncotic) pressure; therefore fluid moves from the interstitial area into the intravascular compartment, a process known as reabsorption (Figure 7-2).

The semipermeable cell membrane allows water to flow freely; therefore fluid flows into the cell from the interstitial area by osmosis. Most electrolytes, however, require a transport system.

The semipermeable cell membrane allows water to flow freely; therefore fluid flows into the cell from the interstitial area by osmosis. Most electrolytes, however, require a transport system.Fluid Excretion

The most common areas for fluid to be excreted from the body are the bowels, skin, lungs, and the renal system. Fluid is lost through the bowels in fecal matter with increased loss during bouts of diarrhea. Sweat

lost through skin can be either profuse or through a more natural occurrence of insensible loss. The respiratory system involves the loss of fluid through exhalation, a normal and constant event. The largest amount of fluid loss, however, occurs through urine output. The urine output of the average individual is approximately 1500 mL/day, although it can be as low as 300-500 mL/day.

lost through skin can be either profuse or through a more natural occurrence of insensible loss. The respiratory system involves the loss of fluid through exhalation, a normal and constant event. The largest amount of fluid loss, however, occurs through urine output. The urine output of the average individual is approximately 1500 mL/day, although it can be as low as 300-500 mL/day.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree