22 Fluid balance and the urinary system

Fluid and electrolyte balance

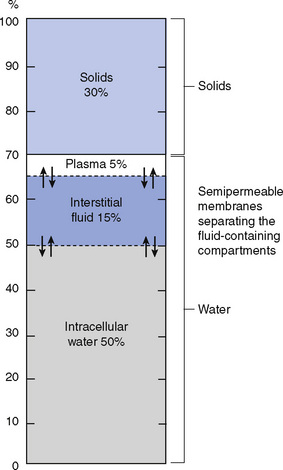

Water forms the greater part of the body cells and the body fluids. Approximately two-thirds (more accurately 60%) of the body weight consists of water. This proportion must be maintained. Of this water, 70% is inside the body cells (intracellular) and the remaining 30% is in the body fluids (extracellular); 15–20% is in the interstitial spaces in the tissues, bathing all the body cells, even the bone cells, and the remaining 10–15% forms the fluid of the blood, i.e. the plasma and the lymph (Fig. 22.1). These three volumes of fluid are separated only by thin semipermeable membranes, the cell walls and the capillary walls; water constantly passes through these walls from one of these areas to the others, though the volume of each remains remarkably constant in normal health.

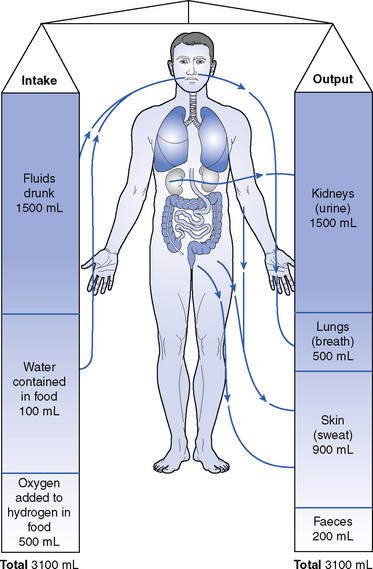

The quantities lost in urine, sweat and water vapour from the lungs vary with conditions. In hot weather and heavy work, more sweat is produced to cool the body, and less urine is passed; at the same time the loss of fluid causes thirst, so that more fluid is drunk. In fever the same changes take place; there is increased loss of fluid and there must be increased intake to balance it (Fig. 22.2).

The urinary system

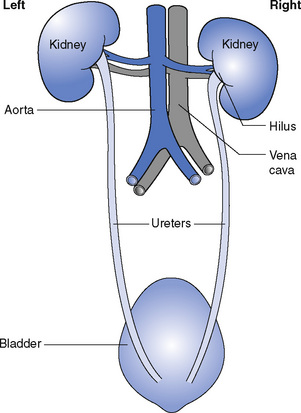

The urinary system consists of the following components (Fig. 22.3):

The kidneys

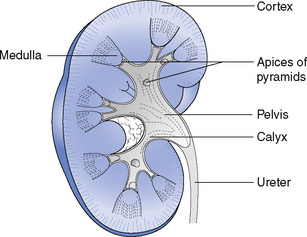

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs (Fig. 22.4) situated in the posterior part of the abdomen, one on each side of the vertebral column, behind the peritoneum. They lie at the level of the twelfth thoracic to the third lumbar vertebrae, though the right kidney is usually slightly lower than the left because of its relationship to the liver.

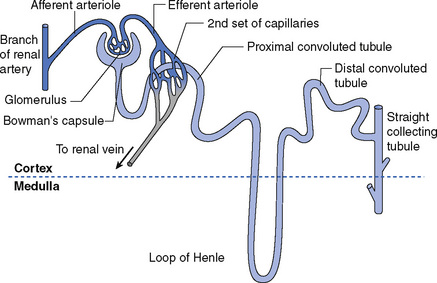

The kidney substance consists of minute twisted tubules called nephrons (Fig. 22.5); there are over a million in each kidney. Each of the nephrons begins in a cup-shaped expansion called the glomerular capsule, from which the tubule leads (Fig. 22.6). Into the cup of each capsule comes a fine branch of the renal artery, forming a tuft of capillaries in close contact with its inner wall; the capillary tuft is called the glomerulus. The arteriole bringing blood to the tuft is called the afferent vessel, and the arteriole that carries the blood away is the efferent vessel; it is slightly smaller than the afferent vessel. The blood in the tuft is under high pressure because of this and because of its nearness to the abdominal aorta.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree