CHAPTER 3 Finding the evidence

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

The basics of searching

Carefully define your clinical question

Information about how to construct a well-formulated clinical question, using the PICO format, was provided in Chapter 2.

Broaden your search if necessary

Once you have identified key terms or phrases you should consider broadening your search, particularly if your initial search yields no relevant articles.

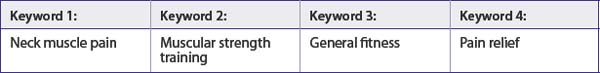

Basics of searching—an example

To illustrate these basics of searching further we will work through a step-by-step example.

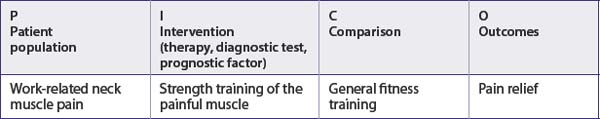

Step 2: Compose your clinical question

| Clients with work-related neck muscle pain | Patients |

| Strength training of the painful muscle | Intervention |

| General fitness training without direct involvement of the painful muscle | Comparison |

| Greater pain relief | Outcomes |

Step 3: Construct the final clinical question

| For clients with work-related neck muscle pain, does strength training of the painful muscle versus general fitness training without direct involvement of the painful muscle result in greater pain relief? |

Step 7: Decide which online resource(s) to search

The online resource that you decide to search in will depend on the type of question that you are asking (for example, intervention, diagnostic, prognostic or qualitative question). As was explained in Chapter 2, for each type of question there is a hierarchy of evidence. This hierarchy should be used to guide your search so that you know what type of study design you are hoping to find when searching. The type of study design that you are looking for will, in turn, influence which online resource(s) you should search in. For example, if your clinical question is a prognostic one related to rehabilitation, then you will be looking for a cohort study (or systematic review of cohort studies). Therefore, there is no point in searching the Cochrane Library, PEDro or OTseeker as these resources do not contain cohort studies. The best resource for you to start your search in would probably be PubMed, using the Clinical Queries feature. All of these resources, and many others, are described in the following section and in the examples at the end of this chapter.

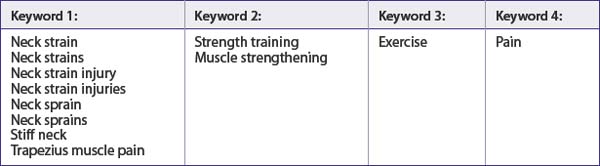

A model of evidence-based information services

In this chapter, we will use a five-level pyramid to discuss the organisation of evidence-based information services.2 This ‘5S’ model (see Figure 3.1) is hierarchical in nature and has:

FIGURE 3.1 The 5S pyramid showing levels of organisation of evidence from healthcare research

Reproduced with permission from Haynes RB, Of studies, syntheses, synopses, summaries, and systems: the “5S” evolution of information services for evidence-based healthcare decisions; American College of Physicians; 20062

Deciding where to start on the pyramid depends largely on the question being asked and what resources are available to you. As explained earlier, you should be guided by the hierarchy of evidence for the type of question that you are asking. Additionally, you will also find that much of the content that is available at the higher levels of the pyramid is aimed at the medical profession and that most of the evidence for nursing and the allied health questions are found in the bottom two levels of the pyramid and, at times, level three. At each level of the ‘5S’ pyramid, users of the evidence must appraise the quality of the evidence presented ensuring that the methods used to generate this evidence were sound. Detailed information about how to critically appraise evidence, once you have found it, is presented in Chapters 4–12 of this book. Each level of the pyramid will now be discussed further, starting at the top of the pyramid, where the best and most highly synthesised evidence can be found.

Systems—first layer (top) of the pyramid

Clinical decision support systems have been developed for various clinical issues, including the diagnosis of chest pain, the management of chronic disease (such as diabetes care) and the timely administration of preventive services (such as immunisations). A systematic review of the effects of computerised clinical decision support systems showed that many improve health professionals’ performance.3 If you have such a system in your workplace, you are lucky as it is likely that you will not need to look further for the best evidence to answer your clinical question. However, most people will not be able to begin their search at the top of the pyramid because systems are relatively rare, existing for only a few diseases or conditions, and usually have a medical focus. Not all health professions have electronic client medical records and, even if they do, many are not integrated with a decision support system that has an evidence-based guideline summarising the current best evidence on a topic of interest. Therefore, if you do not have access to a system that addresses your information needs, you will need to start your search for the current best evidence at the next level down in the pyramid.

Summaries—second layer of the pyramid

Summaries are information resources that provide regularly updated evidence, which is usually arranged by clinical topics. They are considered to be similar to traditional textbook chapters in form and content. Evidence-based clinical guidelines are also located at this level of the pyramid. Summaries provide guidance and/or recommendations for client management and often provide links to other aspects of the disease or condition. Summaries can be found in disease-specific textbooks such as Evidence-based Endocrinology4 but, unless the textbook is accompanied by a website where the content can be regularly updated, the content in a print textbook becomes quickly outdated. Online textbooks that are regularly updated are becoming more common. Medicine has the most of these online textbooks and some of these contain information which may be of interest to allied health professionals or nurses. All of the online textbooks listed below are available on a subscription basis but many workplaces, particularly academic and healthcare institutions, may have institutional subscriptions. Examples of these online textbooks are:

PIER is available online to ACP members but it can be accessed through STAT!Ref (http://www.statref.com/), an online healthcare reference that provides full text access to key medical reference sources and textbooks, some of which are evidence-based resources. STAT!Ref is a subscription-based resource that is usually available in academic or hospital environments where institutional subscriptions exist. PIER is more directive than Clinical Evidence as it contains recommendations rather than evidence summaries.

Synopses—third layer of the pyramid

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree