Chapter 10 Female Reproductive Health Breakdown

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to

STRUCTURE OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

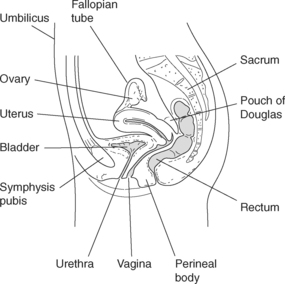

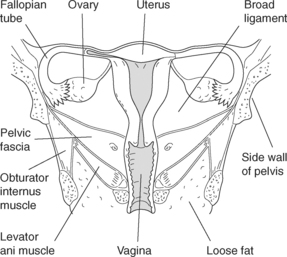

The female reproductive system consists of the internal and external genitalia. The internal genitalia comprise the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina, with the external genitalia including the mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris, introitus, and perineal body (see Figures 10.1 and 10.2). Even though the female urinary tract is separate anatomically from the reproductive structures, their close proximity is a means of potential cross contamination and shared symptomatology between the two structures.

INTERNAL GENITALIA

OVARIES

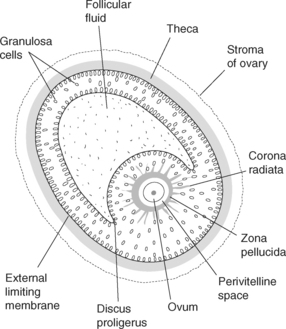

The function of the ovaries is twofold in that they store the female germ cells, or oocytes, and produce the two major female reproductive hormones, oestrogen and progesterone. Structurally, the ovary is composed of an inner medulla containing supportive connective tissue directly attached to the broad ligament. The cortex of the ovary consists of highly vascular tissue where the ovarian follicles are embedded. Each primordial follicle contains an immature egg or germ cell encased in a layer of squamous-like follicle cells. The primary follicle is then surrounded by two or more layers of granulosa cells. These cells protect and nourish the germ cells until the follicle matures and ovulation occurs. Thus the primary germ cell, under the influence of the pituitary and ovarian hormones, becomes a fully developed graafian follicle. During a woman’s reproductive years, one germ cell usually matures each monthly cycle to be extruded from the ovary and engulfed by the fallopian tube fimbriae. This expulsion of the germ cell, or ovulation, occurs as a consequence of the stimulus of the gonadotrophic hormones, follicle stimulating and luteinizing hormones. After ovulation, the ruptured follicle transforms into a structure called the corpus luteum. In the absence of a pregnancy, the corpus luteum degenerates in approximately six months into a corpus albicans. If pregnancy occurs the corpus luteum is than maintained until the placenta is established, taking over the endocrine function1,2.

Prior to birth, the fetal ovary contains over 2 million primordial follicles. By menarche (commencement of menstrual cycles), only approximately 200,000 remain, continuing then to decrease throughout a woman’s reproductive years. Only 300 to 400 are actually released by ovulation during the woman’s reproductive life. Of the remainder, a process termed atresia occurs in over 80%. This process involves the primordial and primary follicles becoming smaller and then being reabsorbed by the body1.

FALLOPIAN TUBES

The fallopian tubes are also called uterine tubes or oviducts, of which there are two. Each tube is a slender, cylindrical and muscular structure approximately 10 cm long. The tube is an extension of the cornu of the uterus and travels to the side walls of the pelvis, turning downwards and backwards before reaching the ovaries. Both tubes communicate with the uterus at the medial end and the ovaries at the lateral end, being supported by the upper folds of the broad ligament. At the ovary end, the fallopian tubes form a funnel-shaped opening with fringed projections or fimbriae. These finger-like projections massage the ovaries at ovulation to help extract the mature ovum1,2.

Travel in the fallopian tubes occurs as a result of two factors:

Further, the fallopian tube provides a passageway through which tubal secretions can drain into the uterus. It should also be noted that the fallopian tube provides a direct passageway between the vagina and the peritoneal cavity. This is, therefore, a direct route for the entry of ascending infection into the peritoneal cavity1,2.

UTERUS

The major portion of the uterine wall is the middle layer or myometrium. This layer has the amazing ability to change in length during pregnancy and labour. The inner layer of the uterus is the endometrium and is continuous with the inner layer of the fallopian tubes and vagina. There are then two layers of the endometrium, a basal and superficial layer. The superficial layer is shed during menstruation, but is then regenerated by the cells of the basal layer. Ciliated cells promote movement of tubal-uterine secretions out of the uterine cavity into the vagina1,2.

CERVIX

In the nulliparous female, the cervix constitutes about 15%–20% of the uterus and is the part that invaginates or projects into the anterior wall of the vaginal canal. It is the outer portion, or ectocervix, that protrudes into the vagina. This ectocervix has a smooth, pinkish appearance due to the squamous epithelial cell covering. The inner, opening canal of the cervix is called the endocervix, containing a lining of columnar epithelial cells, giving it a rough, reddened appearance. Under hormonal influence, the columnar epithelium provides enough elasticity during labour for the cervix to adequately stretch to allow passage of a fetus. The squamocolumnar junction is where the two types of epithelial cells meet. This junction contains the optimal type of cells needed for an accurate Papanicolaou (Pap) test for malignancy screening. If there are endocervical cells present in the Pap test sample, this ensures that the squamocolumnar junction, or transformational zone, has been sampled.

The cervix is richly supplied by blood from the uterine artery. This, therefore, can be a site of significant blood loss during birth. The cervix consists of a connective tissue matrix of glands and muscular tissue. This forms a firm fibrous structure that becomes soft and pliable under the influence of the hormones of pregnancy1,2.

VAGINA

The vaginal walls’ muscular and erectile tissue allows enough dilatation and contraction to accommodate penetration of the penis during intercourse, as well as the passage of the fetus during birth. The membranous vaginal wall, which forms two longitudinal folds and several transverse folds or rugae, contributes to this dilatation1,2.

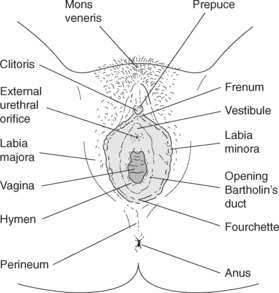

EXTERNAL GENITALIA

The external genitalia, commonly referred to as vulva, are located at the base of the female pelvis in the perineal area. Structures that make up the vulva include the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris and perineal body (see Figure 10.3). Other structures usually considered as part of the vulva include the urethra and anus, although they are not considered to be part of the genital structures.

MONS PUBIS (VENERIS)

The rounded eminence located anteriorly to the symphysis pubis of the bony pelvis is the mons pubis. This consists of a fat pad covered with skin and coarse hair that lies in an upside-down triangular pattern. Under the hormonal influence of puberty, the amount of fat and hair increases and the colour deepens. The skin is abundant with sebaceous glands, which may become infected for a variety of reasons, including changes in diet, normal variations, or poor hygiene. This is also the site of pubic lice infestation1,2.

LABIA MAJORA

Beginning anteriorly at the base of the mons pubis and extending posteriorly to the anus are the outermost lips of the vulva called labia majora. This structure consists of folds of skin and fat, becoming covered with hair at the onset of puberty. The labia majora are rich in sebaceous glands and sweat glands and subject to the same types of problems as the mons pubis1,2.

LABIA MINORA

The vestibule is the area between the labia minora, extending anteriorly from the clitoris to the vagina posteriorly. This is a boat-shaped fossa that contains the ureteral and vaginal opening or introitus, and the Bartholin’s lubricating glands. These glands are located at the posterior and lateral aspects of the vaginal orifice where the labia minora end. The purpose of the Bartholin’s glands is to secrete a thin, mucoid material to lubricate the vestibular area. This is believed to contribute slightly to lubrication during sexual intercourse1,2.

CLITORIS

Anteriorly, the two labia minora join, forming the clitoral hood or prepuce. Just below this structure, anterior to the urethral meatus, the clitoris is located. This structure consists of erectile tissue, rich in blood and nerve supply, which becomes distended during sexual stimulation. The clitoris is homologous to the male glans penis. Stimulation of the clitoris is an important part of sexual activity for women1,2.

PERINEAL BODY

The perineal body or perineum is the tissue located posterior to the vagina and anterior to the anus. This area is composed of fibrous connective tissue and is the site of insertion of several perineal muscles. During childbirth, this area may be torn or incised (episiotomy) to facilitate birth of the baby1,2.

FEMALE SEXUAL MATURITY

Physiological changes that occur during puberty include alterations in reproductive organs, the commencement of menstrual cycles and the development of secondary sex characteristics. The first change in the reproductive organs is the onset of breast budding, which usually occurs at around 10 years of age and may be accompanied by the first appearance of hair on the mons pubis3.

The arrival of the first menstrual period is known as menarche, and usually occurs about two years after the start of breast budding. Just prior to the onset of the first menstrual period, a spurt in somatic growth is often experienced. The age at which menstrual cycles begin is influenced by nutritional status, weight, general health, genetic background, exercise and environmental factors; however, menarche generally occurs at approximately 12–13 years of age4.

Other changes during puberty include development of the breasts and vulva, vagina, uterus and fallopian tubes. Vaginal secretions increase and become more acidic, pubic and axillary hair appears, the pelvis widens and fat is deposited on the breasts, hips and buttocks4.

THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE AND THE CONTROL OF OVULATION

The menstrual cycle is a reflection of the cyclical release of hormones produced by the hypothalamus, pituitary and ovaries1. The hypothalamus controls the release of hormones from the anterior pituitary gland, which in turn regulates ovarian hormone production. Ovarian hormones control changes within the uterus and other parts of the reproductive tract5,6. During each cycle an oocyte is prepared for release at ovulation and, simultaneously, preparations begin within the woman’s body for pregnancy and subsequent lactation1.

The length of a menstrual cycle is the number of days between the first day of menstrual bleeding of one cycle to the onset of bleeding in the next cycle. The median duration of a menstrual cycle is 28 days (a lunar month) but most cycle lengths are between 25 and 30 days4. On the 14th day of a typical cycle ovulation occurs, during which an oocyte is released from the ovary. Menstrual cycles occur regularly throughout a woman’s reproductive life except during pregnancy and lactation5. The menstrual cycle is characteristically most irregular around the extremes of reproductive life, at menarche and menopause4.

THE OVARIAN CYCLE

At puberty, there are many thousands of primordial follicles embedded in the cortex of the ovary. Each of these primordial follicles consists of a primary oocyte (egg cell) surrounded by a single layer of follicle cells1,4. During each cycle a number of follicles will start to mature becoming known as Graafian follicles1,5. One of the follicles will mature at a faster rate than the others and this follicle will be the one that releases an oocyte at ovulation1,4,5. The Graafian follicle comprises the following (see Figure 10.4):

The ovarian cycle can be considered in two phases, the follicular phase and the luteal phase1,5,6. During the follicular phase there is maturation of ovarian follicles and ovulation. The luteal phase involves the development of the corpus luteum from luteinization of the granulosa cells and theca interna cells4. The average ovarian cycle is 28 days with ovulation occurring on day 14. However, there is great variability between cycles both in the individual woman and between women. It is usually the length of the follicular phase that is variable. The length of the luteal phase is generally constant1,4.

FOLLICULAR PHASE

The follicular phase begins with the first day of menstrual bleeding and continues until immediately before ovulation occurs. This phase is initiated by the release of gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the secretion of two gonadotrophins, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland. Under the influence of FSH, a number of follicles will begin to mature but one will mature more quickly than the others1,4.

The main hormones produced by the ovary are oestrogen, progesterone and androgens4. Oestrogen comprises a number of compounds including oestriol, oestradiol and oestrone1,5. LH stimulates the theca cells to produce androgens which are transported to the granulosa cells for conversion to oestrogen. FSH stimulates the granulosa cells to produce the enzymes that convert the androgens to oestrogen1,4,6. Proliferation of the granulosa and theca cells occurs and the follicle further increases in size1. The larger and more mature the Graafian follicle becomes, the greater the amount of oestrogen produced. As oestrogen levels rise, a negative feedback mechanism inhibits the production of FSH, ensuring that the growth and maturation of other follicles is controlled1,4,5,6.

FSH and LH function synergistically to complete maturation of the dominant follicle. The follicle continues to grow and as it reaches maturity, there is a marked rise in oestrogen production. This rise initiates a surge in LH secretion approximately 36 hours before ovulation occurs1,4,6. Just prior to ovulation the primary oocyte completes its first meiotic division, becoming known as a secondary oocyte. The final stage of meiosis will take place on fertilization of the ovum1.

The process of ovulation is assisted by the local secretion of prostaglandins and proteolytic enzymes which facilitate breakdown of collagen in the wall of the follicle1. The oocyte escapes from the follicle still surrounded by the zona pellucida, some follicular fluid and cells6. Some women experience pain at the time of ovulation, known as mittelschmerz. The ovum released at ovulation remains fertile for up to 72 hours5.

LUTEAL PHASE

After ovulation has taken place, the walls of the follicle collapse inward. The remaining tissues become vascularised and change into the corpus luteum (yellow body)4. The function of the corpus luteum is to secrete the hormone progesterone, which has a profound influence on the preparation of the reproductive system for possible pregnancy. If pregnancy does occur, human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) maintains the corpus luteum and progesterone continues to rise. If pregnancy does not occur, the function of the corpus luteum declines by the end of the luteal phase and menstruation is triggered5,6. The corpus luteum then atrophies, becoming the corpus albicans (white body). During this regression, there is a rapid decline in the production of progesterone and oestrogen. When levels become low enough, the anterior pituitary is stimulated to produce FSH and LH and a new ovarian cycle begins1,4.

THE MENSTRUAL (UTERINE) CYCLE

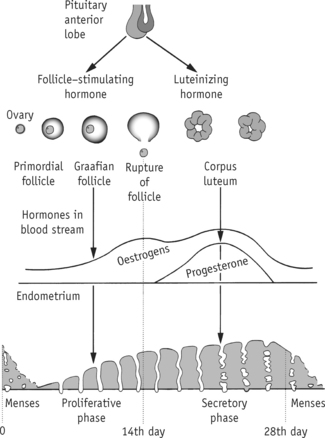

The changing patterns of gonadotrophins and ovarian hormones cause changes to occur within the endometrium of the uterus. This cycle can be considered in three phases, the menstrual phase, the proliferative phase and the secretory phase (see Figure 10.5).

FIGURE 10.5 Menstrual cycle

Source: Henderson, C & Macdonald, S. 2004; Mayes’ Midwifery: A Textbook for Midwives (13th ed.), Ballière Tindall, Edinburgh, Fig. 6.1, p. 89.

MENSTRUAL PHASE

This phase is characterised by vaginal bleeding, known as menstruation or menses. Menstruation typically lasts 3 to 6 days6. Although the first day of bleeding is considered to be the first day of the cycle, physiologically it is the end point of the cycle as it involves the shedding of the endometrium down to the basal layer5. If pregnancy does not occur, the function of the corpus luteum declines and levels of ovarian hormones fall. The endometrium undergoes vasospasm, ischaemic necrosis and sloughing of tissue4. Endometrial tissue and accompanying blood are discarded through menstruation with the aid of uterine contractions stimulated by prostaglandins. These contractions may cause pain, known as dysmenorrhoea. Normal blood loss during menstruation ranges from 30 to 80 mL4. The basal layer of the endometrium is not affected by the menstrual cycle and is, therefore, the foundation for endometrial regeneration6.

PROLIFERATIVE PHASE

This phase begins once menstruation has ceased and ends at the time of ovulation. After menstruation, the inner lining of the uterus or endometrium is very thin. During the proliferative phase, under the influence of oestrogens being produced by the maturing Graafian follicle, the endometrium thickens from 1 mm to 3–6 mm1. The endometrium becomes more vascular and the endometrial glands proliferate. Increased levels of oestrogen also cause cyclical changes in the cervix, vagina and breasts6.

SECRETORY PHASE

This phase corresponds with the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle, spanning from ovulation to the onset of menstruation. Changes occurring during this phase are largely stimulated by the secretion of progesterone from the corpus luteum4. The endometrium and its supporting stroma continue to thicken, blood vessels proliferate, dilate and become coiled. Endometrial glands continue to hypertrophy and begin to secrete fluid rich in glycogen1. Under the influence of oestrogen and progesterone, further changes to the reproductive system occur including to the alveolar system of the breasts, resulting in them feeling heavy and tender4,6. The purpose of these changes is to prepare the reproductive system for implantation of a fertilised ovum and to begin preparation for lactation.

PERIMENOPAUSE AND MENOPAUSE

Perimenopause is the phase during which a woman moves from reproductive life to non-reproductive life. The perimenopausal transition typically begins about four years before menstrual cycles finally cease. During the perimenopause, the ovaries become less responsive to the stimulatory effects of FSH and LH. During this phase, women may experience menstrual irregularity, changes in amount and length of menstrual flow, and reduced fertility7. Women may also suffer menopausal symptoms, such as changes in sexual function, vasomotor symptoms, psychological changes and insomnia8.

Female reproductive life ends with the cessation of menstrual cycles at menopause, which usually occurs at around 47–55 years of age. Menopause is defined as 12 consecutive months of amenorrhoea sometimes accompanied by hot flushes and urogenital atrophy8. Symptoms can, however, be varied or absent.

ALTERATIONS IN STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Disorders of the female reproductive system may have widespread effects on both physical and psychological functions of a woman. These conditions bear close relationships to sexuality and reproductive function, and for these reasons, have the potential to have a significant impact. There is a wide range of health breakdown of female reproductive system, all of which cannot be discussed in this chapter. For this reason the discussions in this section have been divided into benign and malignant conditions9.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree