Chapter 39 Feeding 1

Breast and bottle

INTRODUCTION

BREASTFEEDING

The ideal choice of feed for a healthy infant is breast milk. Breast milk is nutritionally the best feed for infants, and has been shown to promote optimum health, growth, development and immunity against illness (Heinig & Dewey 1996, 1997). There is significant evidence to support the existence of the significant advantages, both to the infant and the mother, of breastfeeding (British Paediatric Association Standing Committee on Nutrition 1994), which are summarised in Box 39.1. Despite the well-recognised advantages of breastfeeding, rates are low in the UK.

The Infant Feeding Survey, published in 2005 reported initial breastfeeding rates of 78% in England, a significant increase from the previous survey carried out in 2000. However, rates of breastfeeding reduced rapidly to only 22% of mothers exclusively breastfeeding their infant at 6 weeks of age; 8% at 4 months of age; and only a negligible number at 6 months of age. There is growing evidence of the lifetime benefits of exclusive breastfeeding and consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO 2003) recommend that all babies be exclusively breastfed until 6 months of age. This is supported by the UK government (DoH 2004).

The reasons why a mother stops breastfeeding vary, but a recurrent issue is the lack of help and support to continue when difficulties are encountered (Hamlyn et al 2002). Social and cultural factors, e.g. early return to work, can also influence a mother’s decision to cease breastfeeding. Lack of knowledgeable support can be a particular issue if the infant is admitted to a children’s ward, especially straight from a maternity unit, as education about breastfeeding for children’s nurses has been sketchy or non-existent in the past. The UNICEF Baby Friendly Initiative (1997) has supported specific guidance for good practice on paediatric units and these should be readily available for paediatric nurses on units where infants are admitted.

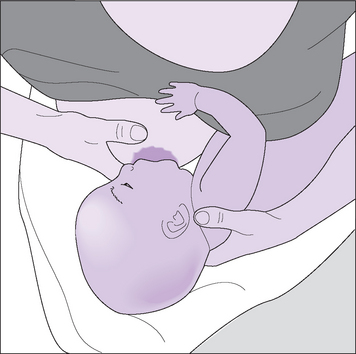

FREQUENCY AND LENGTH OF BREASTFEEDS

Breastfeeding works on a supply and demand process, so the more the infant feeds the more milk is produced, and infant-led feeding is important for an adequate milk supply (Chadderton et al 1997). Many infants feed every 1–2 h in the first few days after birth, and many will feed for long periods, sometimes up to 1 hour. As breastfeeding becomes established, the frequency of feeds reduces to an average of eight feeds over 24 h (Hörnell et al 1999). If an infant continues to feed frequently and is unsettled after a feed, it is possible that the positioning or attachment to the breast is poor and a breastfeeding specialist should review breastfeeding techniques. As breastfeeding is infant-led, the baby should come off the breast of their own accord. If they are still hungry, the second breast should be offered. The sucking pattern of the infant is rhythmical during breastfeeding and changes from quick short sucks to slow deep sucks with short pauses from time to time (Stables & Rankin 2005).

EQUIPMENT

METHOD

This method is based on Chadderton et al (1997).

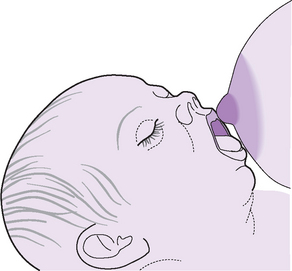

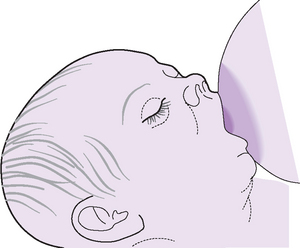

Figure 39.5 Supporting the breast during feeding.

(with approval from UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative at: www.babyfriendly.org.uk)