On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Gain an understanding of the role of families in the lives of older adults. 2. Identify demographic and social trends that affect families of older adults. 3. Understand common dilemmas and decisions older adults and their families face. 4. Develop approaches that can be suggested to families faced with specific aging-related concerns. 5. Identify common stresses that family caregivers experience. 6. Identify interventions to support families. 7. Plan strategies for working more effectively one-on-one with families of older adult clients. What would you do if you were faced with the following situations? • You have been married 45 years. Your husband recently had a severe stroke and cannot communicate. He managed the family finances and made the family decisions. You do not know anything about your financial affairs. • Your parents, in their upper 70s, are mentally competent, but their physical condition means they cannot manage alone in their home. They require all kinds of help and reject any other living situation or paying outsiders for services. • Your father is dying. You promised that no heroic measures would be taken to prolong his life; he did not want to die “with tubes hooked up to my body.” Your brother demands the physician use all possible measures to keep your father alive. • Your father’s reactions and eyesight are poor. You don’t want your children with him when he is driving. He always takes the grandchildren to get ice cream and will be hurt if you say the children cannot ride with him. Although each situation involves medical considerations, these are tough issues and decisions that extend beyond medical aspects (Schmall, 1994): • How much independence do I allow my family member to have and how much risk do I allow him or her to take? • Is my family member fully capable of making his or her own decisions? • When, if ever, should I step in and take control of the situation? • What should I do if my family member refuses help or refuses to make a change? • What should I do if my family member’s actions are putting himself or others at risk? Families play a significant role in the lives of most older persons. When family is not involved, it generally is because the older person has no living relatives nearby or there have been long-standing relationship problems. Nearly 30% of all adults 75 years or older require help with one or more activities of daily living (Sands, 2006). About 7.4% of Americans 75 or older lived in nursing homes in 2006 compared with 8.1% in 2000 and 10.2% in 1990. More than 1.8 million people live in nursing homes (El Nasser, 2007). This means that the majority of care for the elderly is provided in the home environment. Community services generally are used only after a family’s resources have been depleted. However, several demographic and social trends have affected families’ abilities to provide support. These trends include: • Increase in the old-old. By the year 2050, the number of Americans age 65 or older is expected to more than double, while those age 85 or older, who are most likely to use long-term care services, will account for 5% of the population, or triple the size of today’s demographic. The oldest baby boomers are fast approaching retirement age, and we will be ushering in a generation of seniors larger than any previously served by the nation’s health care system. Average life expectancy has increased dramatically over the past century, from 50 years in 1900 to 75+ today. In 1900, 75% of the population died before age 65; in 1995, 70% died after 65. The number of individuals who are 85 or older will increase from 2.3 million in 1995 to 16 million in 2050 (Willging, 2003, Willging, 2006). • Decrease in fertility. A declining birth rate (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2009) means fewer adult children are available to share in the support of aging parents. • Increase in employment of women. Traditionally women have been the primary caregivers. However, in 2008, women comprised 46.5% of the workforce and are projected to comprise 47% by 2016. Approximately 75% of women work full-time, and 25% work part-time. Although employed women often provide as much support as their unemployed counterparts, they often sacrifice personal time. Women aged 55 to 67 reduced their at-work hours by an average of 367 hours, or 41%, to provide some level of care to their parents. A fairly small percentage (14%) leave the workforce or take an early retirement to provide care (Quick Stats on Women Workers, 2008), but many rearrange work schedules, reduce work hours, or take a leave of absence without pay. Changes in employment status have implications for the financial security of these women in their own later years. • Increase in mobility of families. Families today may live not only in a different city from their older relative but also in a different state, region, or country. In fact, according to 2003 U.S. Census Bureau data, 14% of the U.S. population has migrated since the last census. Geographic distance makes it more difficult to directly provide the ongoing assistance an older family member may need. • Increase in divorce and remarriage. Since the 1950s divorce rates have risen among all age groups. The current divorce rate in the United States for first marriages is 41%, for second marriages, 60%, and for third marriages, 73% (Divorce Rate in America, 2009). Divorce and remarriage can increase the complexity of family relationships and decision making and can affect helping patterns. Difficulties can arise from family conflicts, the different perspectives of birth children and stepchildren, and the logistics of caring for two persons who do not live together. However, in some situations, remarriage increases the pool of family members available to provide care. • Elderly providing as well as receiving support. Many elderly receive financial help from adult children, but many older adults give support (money, child care, shelter) to their adult children and grandchildren. • Increased variety in “supportive services” for the elderly. According to the National Investment Conference (NIC), a nonprofit education forum based in Annapolis, Maryland, the senior-housing market is expected to more than triple, growing from an estimated $126 billion in 2005 to $490 billion by 2030, and the largest area of growth will be in the assisted living sector. The number of providers of assisted living services has increased by 49.4%, and the number of beds available for assisted living has increased by 114.8%. (The trend is expected to continue: a 150% increase in the number of assisted living units may be seen by 2030.) In contrast, the number of skilled nursing providers has grown by only 22.2%, and the number of beds increased by only 10.4% (Raymond, 2000). Many families face the question, “What should we do?” when an older family member begins to have problems living alone. Common scenarios heard from families include the following (Schmall, 1994): • “Dad is so unsteady on his feet. He’s already fallen twice this month. I’m scared he’ll fall again and really injure himself the next time. He refuses help, and he won’t move. I don’t know what to do.” • “Mom had a stroke, and the doctor says she can’t return home. It looks like she will have to live with us or go to a nursing facility. We have never gotten along, but she’ll be very angry if we place her in a nursing facility.” • “Grandmother has become increasingly depressed and isolated in her home. She doesn’t cook, and she hardly eats. She has outlived most of her friends. Wouldn’t she be better off living in a group setting where meals, activities, and social contact are provided?” The nurse plays an important role in • Providing an objective assessment of an older person’s functional ability • Exploring with families ways to maintain an older relative in his or her home and the advantages and disadvantages of other living arrangement options • Helping families understand the older person’s perspective of the meaning of home and the significance of accepting help or moving to a new environment • Is my family member concerned about the impact of costs on his or her or my personal financial resources? • Does my relative think he or she does not need any help? • Does my family member view agency assistance as “welfare” or “charity”? • Is my family member concerned about having a stranger in the house? • Does my relative believe that the tasks I want to hire someone to do are ones that he or she can do or that “family should do,” or does he or she feel that it would not be done to his or her standards? • Does my family member view accepting outside help as a loss of control and independence? • Are the requirements of community agencies—financial disclosure, application process, interviews—overwhelming to my family member? Depending on the answers to these questions, it may be helpful to share one or more of the following suggestions with the family (Schmall, Cleland, & Sturdevant, 1999): • Deal with your relative’s perceptions and feelings. For example, if your older mother thinks she does not have any problems, be objective and specific in describing your observations. Indicate that you know it must be hard to experience change. If your father views government-supported services as “welfare,” emphasize that he has paid for the service through taxes. • Approach your family member in a way that prevents him or her from feeling helpless. Many people, regardless of age, find it difficult to ask for or accept help. Try to present the need for assistance in a positive way, emphasizing how it will enable the person to live more independently. Generally, emphasizing the ways in which a person is dependent only increases resistance. • Suggest only one change or service at a time. If possible, begin with a small change. Most people need time to think about and accept changes. Introducing ideas slowly rather than pushing for immediate action increases the chances of acceptance. • Suggest a trial period. Some people are more willing to try a service when they initially see it as a short-term arrangement rather than a long-term commitment. Some families have found that giving a service as a gift works. • Focus on your needs. If an older person persists in asserting, “I’m okay. I don’t need help,” it can be helpful to focus on the family’s needs rather than the older person’s needs. For example, saying, “I would feel better if…” or “I care about you and I worry about…, or will you consider trying this for me so I will worry less?” sometimes makes it easier for a person to try a service. • Consider who has “listening leverage.” Sometimes an older person’s willingness to listen to a concern, consider a service, or think about moving from his or her home is strongly influenced by who initiates the discussion. For example, an adult child may not be the best person to raise a particular issue with an older parent. An older person may “hear” the information better when it is shared by a certain family member, a close friend, or a doctor (Box 6–1). Until about 20 years ago, there were only two options for the elderly who could no longer live alone: move in with their children or move into a long-term care facility. In the mid-1980s, a new option was born: assisted living. Many elderly people needed help with things like housekeeping, meals, laundry, or transportation, but otherwise, they were able to function on their own. Baby boomers latched onto this concept, and the industry has grown exponentially. Perhaps the fastest growing care facility option is the continuing care retirement community (CCRC). These CCRCs often look a lot more like four-star resorts than long-term care facilities. Amenities may include restaurants, pools, fitness centers, and spas. Nonetheless, the attraction of CCRCs is health care for life. This type of community typically allows residents to live independently as long as they can and gives them access to more care, in the same location, when, and if, they need it. Today there are 1800 CCRCs nationwide, and they’ve been growing at a rate faster than nursing homes and assisted living facilities combined (Gengler, 2009). • “It was easier to bury my first husband than to place my second husband in a nursing home.” • “My parents have lived together in the same house for more than 50 years. Even though they know that they need more help and have agreed that they need to move where they can get more help, they are having a very difficult time coming to grips with the necessity to downsize into a retirement apartment.” As important as stressing the need for long-term care is dealing with the family’s feelings about placement. Many families view facilities negatively because of what they have seen in the media concerning neglect, abuse, and abandonment. Cultural considerations can also affect feelings about placement (see Evidence-Based Practice Box, Long-distance Care Giving). including (1) pressures and comments from others (“I would never place my mother in a care facility,” or “If you really loved me, you would take care of me”); (2) family tradition and values (“My family has always believed in taking care of its own—and that means you provide care to family members at home”); (3) the meaning of nursing facility placement (“I’m abandoning my husband,” “I should be able to take care of my mother, She took care of me when I needed care,” or “You do not put someone you love in a nursing facility”); and (4) promises (“I promised Mother I would always take care of Dad,” or “When I married, I promised ‘till death do us part’”). For more information, see Questions to Consider When Moving from Independent Living to a Supervised Living Facility (Box 6–2; Box 6–3) and Internet Resources (Table 6–1). TABLE 6–1 INTERNET RESOURCES FOR CAREGIVERS The use of life-sustaining procedures is another difficult decision, especially when family members are uncertain about the older person’s wishes or they disagree about “what Mom (or Dad) would want.” The main interests of patients nearing the end of life are pain and symptom control, financial and health decision planning, funeral arrangements, being at peace with God, maintaining dignity and cleanliness, and saying goodbye (Auer, 2008). It is important for the nurse to realize that life’s final developmental stage ultimately ends in death. Thus, end-of-life decisions are common for most patients and their families. Often this process does not begin until after the patient has lost the ability to participate in the decision. Some patients and families may need repeated reminders to handle these decisions. Goal setting can be a useful tool to help them along. In addition, the caretaker could mention that they have completed some of the same planning for themselves (Auer, 2008) (Table 6–2). TABLE 6–2 End-of-life caregiving by health care professionals differs greatly from that provided by family members. For health care professionals, there is usually a wealth of experience to draw from and support from colleagues to share in the burdens. Families generally do not have the same life experiences to draw from in these situations. In a study by Phillips and Reed (2009), eight themes were identified to form the core characteristics of end-of-life caregiving: 1. It is unpredictable. Each crisis could be the last or just the next in a series of crises. 2. It is intense. It is constant and engulfing. There is a feeling of overwhelming responsibility that cannot be shared. 3. It is complex. Complex treatment regimens must be balanced with complex interpersonal relationships with the patient and other family members. 4. It is frightening. Situations such as falls, bleeding, behavior problems, or medication reactions frighten many caregivers. 5. It is anguishing. Watching the suffering of a beloved family member causes many caregivers severe angst. 6. It is profoundly moving. There are many precious moments with spiritual or sacred overtones. 7. It is affirming. Bonding with the elder patient is a moving experience. 8. It involves dissolving familiar social boundaries. Caregivers and elders share intimacies such as toileting, changing diapers, or catheter care, which would otherwise not be shared. Driving is a critical issue for seniors—and for this country. Older drivers are more likely to get into multiple-vehicle accidents than younger drivers, including teenagers. The elderly are also more likely to get traffic citations for failing to yield, turning improperly, and running red lights and stop signs, which are indications of decreased driving ability. Car accidents are more dangerous for seniors than for younger people. A person 65 or older who is involved in a car accident is more likely to be seriously hurt, more likely to require hospitalization, and more likely to die than younger people involved in the same crash. In particular, fatal crash rates rise sharply after a driver has reached the age of 70 (Senior Citizen Driving, 2008). If family members will be addressing the issue of driving with an older relative, the nurse could suggest they first check some of the resources in Table 6–3. TABLE 6–3 ONLINE RESOURCES FOR SENIORS WHO DRIVE Family caregiving is primarily provided by the adult children of the elderly person. Often the varying levels of participation among siblings can cause stress within the family. It is important for the nurse to recognize the types and levels of family caregiving (Willyard, Miller, Shoemaker, & Addison, 2008): Routine Care—regular assistance that is incorporated into the daily routine of the caregiver Back-up Care—assistance with routine activities that is provided only at the request of the main caregiver Circumscribed Care—participation that is provided on a regular basis within boundaries set by the caregiver (i.e., taking Mom to get her hair and nails done every Saturday) Sporadic Care—irregular participation at the caregiver’s convenience Dissociation—potential caregiver does not participate at all in care Providing care to frail, dependent older adults is increasingly common because of the rapidly aging population. While nearly a quarter of caregivers are spouses, 70% to 80% of all parental caregiving is still provided by middle-aged daughters. In addition, the type of care provided for parents by women is different than that provided by men. Just as the age-old concepts of “women’s work” and “men’s work” imply, there is a division of labor in family caregiving. Women are most likely to handle the more time-consuming and stressful tasks like housework, hygiene, medications, and meals. Men are more likely to handle things like home maintenance, yard work, transportation, and finances (Willyard et al, 2008). A family member with a dementing illness such as Alzheimer’s will require increasing levels of support and assistance as the disease progresses (see Evidence-Based Practice Box). The need can progress to where help is required 24 hours a day. Caregivers of dementia patients often report symptoms of tiredness and depression because of the high levels of stress (Topo, 2009).

Family Influences

Role and Function of Families

Common Late-Life Family Issues and Decisions

Changes in Living Arrangements

Making a Decision about a Care Facility

ORGANIZATION

URL

RESOURCES

Administration on Aging

http://www.aoa.gov

Information about insurance, lifestyle management, finances, nursing homes, assisted living, and living independently.

AARP

http://www.aarp.org

An excellent site with many topics and links of interest to older persons and their families.

American Health Care Association

http://www.ahcancal.org

Association for long-term care includes guide to choosing a nursing facility. The guide is similar to the one from Medicare but has an extensive assessment guide to help in the decision.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

http://www.medicare.gov

“Guide to Choosing a Nursing Home,” which includes long-term care options, definitions, payment for services and care, how to assess a nursing home, and issues of nursing home living.

National Association of Professional Geriatric Care Managers

http://www.caremanager.org

Describes role, qualifications, and education of care managers; guidance on selection of a qualified person; and search for care manager by zip code function.

National Family Caregivers Association

http://www.nfcacares.org

Information about caregiving and chat rooms for caregivers.

Where to Turn

http://www.where-to-turn.org

Information on where to get help for any type of situation, including a section entitled “Senior Circuit”

End-of-Life Health Care Decisions

TYPE OF DOCUMENT

DEFINITION

SIGNATURE

Do Not Resuscitate Order

Executed by a competent person indicating that if heartbeat and breathing cease, no attempts to restore them should be made.

Physician/ Nurse Practitioner /patient (state law dependent)

Health Care Proxy/Medical Power of Attorney

Designates a surrogate decision maker for health care matters that takes effect on one’s incompetency. Decisions must be made following the person’s relevant instructions or in his or her best interest.

Patient/witnesses (state law dependent)

Living Will

Directs that extraordinary measures not be used to artificially prolong life if recovery cannot reasonably be expected. These measures may be specified.

Patient/witnesses (state law dependent)

Advanced Health Directive

Explains person’s wishes about treatment in the case of incompetency or inability to communicate. Often used in conjunction with a Health Care Proxy or Power of Attorney.

Patient/witnesses (state law dependent)

The Issue of Driving

PROGRAM

URL

FEATURES

AARP Driver Safety

http://www.aarp.com

AARP Driver Safety courses designed for older drivers; helps them hone their skills and avoid accidents and traffic violations. Features information on classes and on senior driving in general, including FAQs, driving IQ test, and close call test.

Senior Drivers

http://www.SeniorDrivers.org

Features videos, pictures, and text presentations to help seniors learn to drive more safely. Topics include exercising for driving safety, adjusting your car for driving safety, handling common and difficult driving situations, and handling emergencies.

Driving and the Elderly

http://www.ahealthyme.com/topic/srdriving

(Blue Cross of Massachusetts) “How do I know if I should stop driving?”

Physician’s Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers

http://www.ama-assn.org

New 226-page guide includes checklists for vision and motor skills to assist physicians in evaluating the ability of their older patients to operate a motor vehicle safely.

Aging Parents and Elder Care

http://www.aging-parents-and-elder-care.com/Pages/Checklists/Elderly_Drivers.html

Checklist: When to put the brakes on elderly drivers.

Family Caregiving

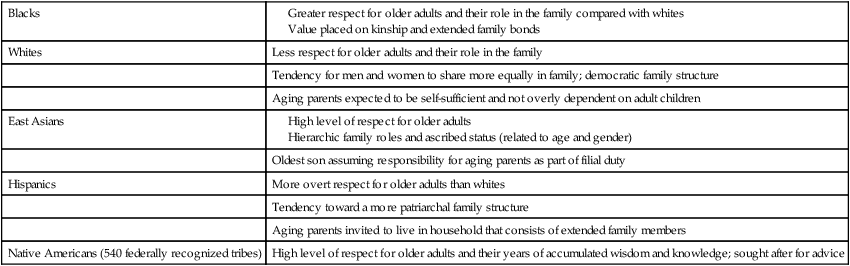

Family Influences

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access