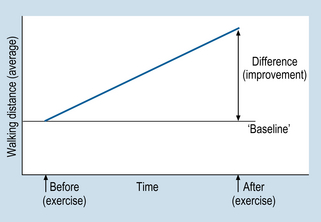

7 In this chapter, we will focus on an experimental design referred to as the randomized controlled trial (RCT) which is an experimental research design aimed at assessing the effectiveness of a clinical intervention. Our aim is to show how RCTs are used to demonstrate that an intervention is the cause of a subsequent effect(s). RCTs are considered by many researchers and clinicians to be the premier type of evidence for the effectiveness of clinical interventions. The specific aims of this chapter are to: 1. The cause must precede (occur before) the effect. 2. The cause and effect co-vary. If the cause occurs then so does the effect. 3. If the cause does not occur, then the effect does not occur. The first criterion is quite simple. For example, if we say that injury to the person’s arm is the cause of that person’s reported pain, we of course assume that the injury was sustained prior to the onset of the pain. Clearly, if the pain had been already present, the injury would not be seen as the cause of the pain. Second, we assume that there will be ‘concomitant variation’ between the injury and the pain. The worse the injury, the more severe the pain. As the injury recovers, a decrease in the level of pain can be expected. In general, we are establishing evidence for the existence of a causal relationship between the cause and the effect. As a hypothetical example, consider the introduction of an exercise program for cardiac patients, which aimed at increasing mobility, and thereby improving health. The patients were also smokers, and were strongly encouraged to give up smoking. The researchers used ‘distance walked by patients’ (in a specified time period) as an indicator of the effectiveness of the program. Figure 7.1 represents (without showing numbers) the average walking distances before and after the exercise program. There is clearly a difference between before and after (i.e. an improvement from baseline). However, was this improvement caused only by the exercise program, or by confounding extraneous variables, or a combination of both? Consider the following plausible alternative explanations for the difference shown in Figure 7.1: 1. The improvement might have been due to natural recovery; the patients’ mobility might have improved independently of the exercise program. This is referred to as a threat to internal validity due to maturation. 2. The improvement might have been due to other factors, such as the reduction in, or cessation of, smoking among some of the patients, resulting in an average increase in walking distance. Such confounding extraneous variables are referred to as history. 3. The improvement might have been due to a placebo effect. Placebo effects (see below) are associated with patient expectations of potential benefits of the intervention. In the example outlined above, the expectations of the patients, rather than the exercise itself, might have been the actual cause of the improvement. 4. An important source of bias is observer bias which refers to researchers unknowingly influencing the results of a study by holding expectations regarding the outcome. In the present hypothetical example, the researchers may anticipate that the exercise program will improve mobility. The above explanations illustrate the influence confounding extraneous variables. That is, each is concerned with factors that are present at the same time as the intervention and which may have produced the observed effect. Internal validity refers to the ability of a researcher to attribute differences (e.g. Fig. 7.1) to the effect of the independent variable. Maximizing internal validity is important for quantitative research designed to demonstrate causal effects. In order to ensure internal validity, researchers must control for the effects of confounding and bias. Experimental designs are particularly well-suited for controlling for the potential influence of confounding factors. Randomized controlled trials employ experimental designs that are applied for evaluating the efficacy of interventions. Let us re-examine the investigation outlined in Figure 7.1 in terms of the impact upon internal validity when we use a control group in the study. 1. Assess the walking distances of the patients in a pre-treatment test. 2. Assign participants into experimental or control groups by matching on the basis of pre-test performance, and random assignment within pairs. a. experimental intervention (exercise program, walking, diet and smoking reduction) b. control intervention (an alternative activity, walking, diet and smoking reduction). 4. Test both groups on walking distance, following the treatment. The results of this fictional study are presented in Figure 7.1. 1. Natural recovery. Both control and experimental groups had the same time to recover or deteriorate; it is unlikely that this factor explains the difference. 2. Confounding due to other interventions. Both groups had walking, smoking decrement and diet. It is unlikely that the difference between the post-test results shown in Figure 7.1 would be due to confounding factors. 3. Placebo effect. Given that this is not a double-blind trial, the bias due to expectations remains uncontrolled with this design.

Experimental designs and randomized controlled trials

Introduction

The concept of causality

Confounding and bias in research studies

The use of control groups in applied health research

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access