Web Resource 4.1: Pre-Test Questions

Before starting this chapter, it is recommended that you visit the accompanying website and complete the pre-test questions. This will help you to identify any gaps in your knowledge and reinforce the elments that you already know.

Learning outcomes

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Explain what is meant by experiential learning

- Explain types of knowledge and ways of knowing

- Describe what is meant by reflection

- Identify the stages of the reflective process

- Identify models of reflection used in practice

Learning through Practice

Stuart (2007) states that it is impossible to provide healthcare and social care students with a set of rules, guidelines and behaviours to prepare them to become competent practitioners. If it were possible, the advantage of preparing practitioners this way would be to reduce the risks of practitioners failing to provide a good service. But Schön (1992) claims that such a technical–rational approach would not prepare practitioners for the real situations of practice, which can be messy, unpredictable and unexpected. Schön describes a high hard ground where these research-based theories could be easily used but states that practitioners would not be fully prepared to deal with the ‘swampy lowlands of practice’ (p 45). By this he is referring to those aspects of practice that cause the greatest concern but to which rules and regulations cannot be applied. Schön states that these areas of practice require the intuitive artistry of the expert practitioner. He also argues that, as professional knowledge and practices constantly change, practitioners have to regularly update their own knowledge and practices so rules and regulations would need to be constantly updated.

Stuart (2007) states that we should be using a model of preparation for professional practice that adopts a holistic approach and does not rely on such regulatory approaches. This model should have practice experience as a main focus. In 1938 Dewey argued that all learning can be viewed as experience; since then there has been a growing consensus that experiences form the basis of learning (Wigens 2006). Students can be supported to interact with the practice environment so that they learn through practice and discover meaning from experiences. Wigens (2006) states that experiential knowledge is professional knowledge from experiences.

Kolb (1984) defined experiential learning as knowledge created through the transformation of experience. It has been acknowledged since 1926 that experience is the richest resource for adults’ learning (Lindeman 1926, cited in Stuart 2007). But what students do, see and hear during practice can remain at a superficial level unless they are stimulated to critically analyse their observations and question the meaning of the experience. Students also need to be stimulated to apply theory to practice. Practice is complex; as well as using theoretical content from several sources, students need to learn about patients’ and clients’ needs and problems, learn to analyse those needs, problem solve, evaluate the effectiveness of care and make changes as appropriate. Stuart claims that effective practice requires a high level of intellectual functioning – application, synthesis and evaluation.

Boud et al (1985) raise the following questions:

- What turns experience into learning?

- What specifically enables students to gain maximum benefit from the experiences that they encounter?

- How can they apply their experiences to new contexts?

- Why do some students appear to benefit more than others?

Boud et al (1985) consider experience to be an event with meaning. They see it is an essential part of the experience and not just an observation, but an active engagement with the practice environment. They do not see an experience as a single occurrence; Dewey 1935 (cited in Boud et al 1985) considers educational experiences as having continuity and integrating with each other so that every experience should do something to prepare the student for the next experience.

Activity 4.1

What factors may influence how a student responds to a new experience in practice?

The response of students to new experiences is determined by their own past experiences as presuppositions and assumptions have been developed. Students come to practice with their expectations, knowledge, attitudes and emotions. These factors influence the construction and interpretation of what they experience. This means that the way in which one student reacts or responds to a situation will not be the same as another. Stuart (2007) argues that students come to clinical areas with memories, feelings and knowledge of health and social care, even if they have not previously experienced this type of organisation. Planning practice experiences is therefore important: the mentor needs to provide continuity rather than separate and discrete experiences. Students also need to be supported by the mentor to make the links between experiences, so that they can see new whole pictures which give a deep approach to learning. Students seek to understand what they are learning from the current experience and relate it to previous experiences that they have had (Stuart 2007).

Boud et al (1995) consider that experience cannot be considered in isolation to learning. They argue that, although experience is the basis of learning and the stimulus for students to learn, it does not necessarily lead to learning unless the student is actively engaged with it. Stuart (2007, p 251) quotes Aitchison and Graham (1989) who state that:

Experience has to be arrested, examined, analysed, considered and negated in order to shift it to knowledge.

To learn from experience it does not have to be recent. Stuart (2007) states that we return to the same experience over and over again and draw different meanings and conclusions every time.

Activity 4.2

Can you think of an experience that you have revisited over and over again?

This experience could be something in your personal life as well as professionally.

My experience occurred when I was working as a ‘bank nurse’ while I was at university. I was a relatively inexperienced staff nurse and I was asked by the nurse in charge to give a patient insulin before her evening meal. The nurse checked the insulin with me but instructed me to change the needle on the syringe because the patient was a woman who was overweight. I was not happy with this decision and questioned why this was necessary. After a discussion, I did what I was told.

I revisited this experience on several occasions because I did something with which I did not agree. I thought about the reasons why I had done this – I was unsure of my own knowledge and skills, I was intimidated by the nurse in charge, I was ‘only’ a bank nurse, and I thought about the effects on the patient. I can say that I have learnt from it. I learnt that I was not really a knowledgeable doer at the time; some of that was my lack of confidence in what I could or thought I knew and could do. I also reflected on whether I had the practical knowledge. Practical knowledge relates to knowing how to do things and developing the skills needed to carry them out. This knowledge is part of the professional craft (Tichen et al 2004). Personal knowledge, influenced by the practitioner’s background, culture, people and events with which they interact, comes from reflecting on events and making sense of situations. Experience filters into the unconscious until re-emerging as intuitive knowing – professional knowledge. This suggests that the practitioner needs time for this knowledge to be acquired; it does not happen overnight. The practical, personal and professional knowledge interacts and merges. I did not have the professional knowledge but I was a novice practitioner so I needed to stick to the rulebook. What the staff nurse told me to do was perhaps not incorrect but what she did lack were the communication skills to develop my understanding of the situation. At that time I did not have the confidence in my practical ability to question her practices.

Boud et al (1985) believe that learning occurs over time and meaning may take years to become apparent. Only the person experiencing this scenario can ultimately give meaning to the experience because it is the individual’s (in this case, mine) interaction with the learning and previous experiences that help to interpret this experience.

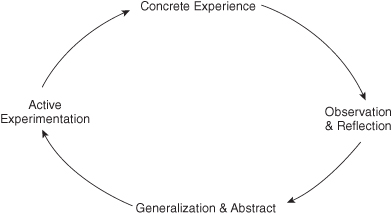

Stuart (2007) concludes that the emphasis in experiential learning is on the process of learning. It comes from the assumption that ideas are not fixed but are continually derived from experience. Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning model emphasises the importance of experience in learning. Kolb sees learning as a four-stage cycle in which the here-and-now personal experience is real and concrete and forms the focal point for learning (Figure 4.1). The core of the model is the translation of experiences into concepts through reflection. These concepts are then used to guide and inform new experiences (active implementation).

A model for Learning through Experience

Stuart (2007) advocates a model with four phases which focus on skills and strategies that influence how a student engages with an experience in practice:

The Preparatory Phase

This focuses on:

- the student as a learner

- developing noticing skills

- developing intervening skills.

During this phase students focus on learning and the reason why they are in practice, which motivates them to take steps towards achieving their goals. They explore what is required of them, how they can contribute, what their role may be, what they can learn, how they can use their knowledge and skills and what they have learnt from previous experiences. Boud et al (1985) consider noticing and intervening skills as enhancing learning through experience. They define noticing as becoming aware of what is happening in and around oneself. Noticing is active and seeking and involves a continuing effort to be aware of what is taking place in oneself and in the practice environment According to Stuart (2007) students also need to be aware of the following:

- How they are acting

- What they are thinking

- How they are feeling.

Being aware of how one feels is important because if emotions are neglected the student is likely to become stressed which will inhibit learning.

Noticing provides the student with the basis of becoming more involved in a practice situation and enables them to reflect-in-action (Schön 1992) because the student becomes more aware of how decisions are made to inform actions taken.

Intervening skills are when a student takes an initiative and is active in the event (Stuart 2007). This can be a verbal or physical action within the learning situation. Stuart states that looking on is not a substitute for active involvement, because the student who has an active approach to the experience is more likely to learn from it.

Activity 4.3

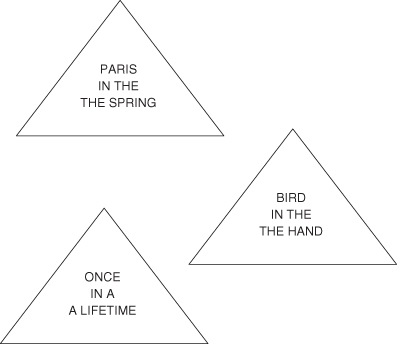

Stuart (2007) states that noticing – paying attention to detail, noticing what occurred – is the starting point for learning. Students need to be directed to use these skills so that they notice things that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

What do you notice about the following?

The Experiencing Phase

This is where the student reflects-in-action. Teaching and learning strategies determine how the student engages with and reflects during the experience:

- Sharing, explaining, pointing out

- Questioning and challenging

- Allowing to experiment

- Giving feedback on performance.

In this phase the role of the mentor is to facilitate the student’s reflection and interventions. The student needs to be supported to make judgements about when and where to take the initiative and what the intervention should be. Reflection can lead to recognition of the student’s feelings and thoughts about the intervention which, according to Stuart (2007), influences the quantity and quality of the learning taken from the experience. This will influence the student’s ability to transfer learning from this experience to others. The student can encounter difficulties in this phase because the practice area can place demands on the student such as the patient/client condition, the need for care and attention, as well as the mentor’s expectations of them.

The Processing Phase

This is where the experience is reflected on. Stuart identifies three main stages for reflecting on experience:

1. Description of the experience

2. Processing through critical analysis

3. Synthesising and evaluating.

After the experience the student is supported to further reflect. Reflecting after the event is one of the most helpful ways of learning from experience (Boud et al 1985). Feelings and cognitions are interrelated in this phase and learning is influenced by the socioemotional context in which it occurs. The student’s presentation of their observations, actions, behaviours and feelings need to be acknowledged by the mentor and worked through.

Outcomes and Actions: Linking Learning to Action

Learning is linked to action so students need to be supported to specify the actions that they intend taking so that they can consider the changes in practice and behaviours that they want to incorporate into future experiences (Stuart 2007).

Steinaker and Bell (1979) suggest a similar approach and identified five levels of experiential learning crucial to supporting students in practice:

1. Exposure: inactive participation; the student observes the mentor undertaking a skill

2. Participation: the student is actively involved in the skill under the supervision of the mentor

3. Identification: the student performs the skill competently with minimal supervision from the mentor

4. Internalisation: the student takes ownership of the skill and feels comfortable in its application

5. Dissemination: the student can transfer the skill to other environments and applications. The student can confidently demonstrate the skill to others.

Considering the scenario of Lizzie from Chapter 1 again.

Scenario 4.1

This was Lizzie’s second clinical placement – a respiratory medical ward which, it seemed to Lizzie, was always manic. Lizzie felt totally out of her depth although the rest of the staff, including the other student who was a third year, seemed to know what they were doing. This intimidated Lizzie; she felt scared to ask for help in case she was thought to be stupid and slow – after all this was her second placement so she should know what she was doing by now, she was 6 months into her course.

But then again, she wasn’t sure who to ask for help because she seemed to work with different members of staff on every shift.

Lizzie had started to dread coming on to the ward for her shifts and panicked when she was asked to do anything by the staff or even by a patient. She couldn’t think clearly and she couldn’t remember how to do even the simplest of tasks.

On one shift, after receiving the handover from the night staff, Lizzie was allocated to work with the ‘red team’ for the morning. The team leader, who was a staff nurse, asked Lizzie to go and shave Mr A. Straightaway Lizzie felt the familiar wave of panic inside and struggled to control it. ‘I can do this’ Lizzie told herself as she shaved Mr A’s face, chest and pubic regions.

Lizzie is at the exposure level so she needs a mentor to take supportive and motivational roles (to stimulate interest).

Participation will occur as Lizzie becomes confident to actively carry out skills under the supervision of her mentor. The mentor should encourage Lizzie, give her praise and set her achievable targets so that Lizzie gains confidence.

Over time and with practice, Lizzie will move to the identification level where she will be able to demonstrate skills competently and with minimal supervision. The mentor at this stage has to balance standing back while at the same time safeguarding the student and the patient/client.

Once Lizzie has reached the internalisation level she will demonstrate confidence in her own ability. At this level the mentor must sustain Lizzie’s interest and develop her further.

At the dissemination level Lizzie will have the ability to transfer the skills to new areas of practice. Lizzie and her mentor should reflect on her achievement and accomplishment of skills and the confidence that has been gained. The mentor will reinforce the message that new challenges and experiences should be embraced because life-long learning is part of professional development.

Web Resource 4.2: Reflective Practice

Web Resource 4.2: Reflective Practice

Please visit the accompanying web page to access a power point presentation that summarises the key aspects of reflection.

Activity 4.4

- Reflect on how these five levels of learning relate to you as a mentor. Can you recognise these levels in students whom you have supported?

- How do they relate to the way that you support students?

Consider the following:

Sally is a 19-year-old student on her second placement. At your first meeting with Sally you judged her as being very nervous and lacking confidence. She is supposed to be working with you this morning but you have a busy schedule with meetings and a member of staff has just rang in sick. Ideally you would like Sally to have a calmer introduction to the unit. What can you do?

There are two options. You could have Sally shadow you while you deal with issues but this might frighten her further.

You could ask a more junior member of the team to orient Sally to the unit and introduce her to other members of the team. The decision that you make would be based on your judgement of Sally’s ability to deal with the pressures and demands of the unit.

Students need support and supervision in practice. As previously stated, mentors exhibiting the characteristics that students perceive as helpful and valuable will facilitate the student’s learning.

What is Reflection?

Boud et al (1985) state that reflection is more than just daydreaming; it is perusal with intent. In relation to professional education, reflection has a specific meaning relating to a complex and deliberate process of thinking about and interpreting experience in order to learn from it (Boud et al 1985).

Activity 4.5

What does the term ‘reflection’ mean to you?

Boud et al (1985) state that reflection is: ‘a generic term for those intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to new understanding and appreciations’ (p 32).

Boyd and Fale (1983) define reflection as ‘the process of internally examining and exploring an issue of concern, triggered by an experience, which creates and clarifies meaning in terms of self, which results in a changed conceptual perspective’ (p 32).

Dewey (1938) was one of the first people to define reflection. He saw it as turning over in your mind a subject and giving it serious consideration. This is possibly a definition that most people can relate to. We all reflect on events inside and outside the professional context.

Jasper (2007) states that reflection is an in-depth consideration of events by oneself with or without critical support. The reflector attempts to work out the following:

- What happened?

- What I thought or felt about it?

- Why?

- Who was involved?

- When?

- What these others might have experienced and thought about it?

Jasper states that reflection is looking at whole scenarios from as many angles as possible – people, relationships, situation, place, timing, chronology, causality and connection – in an effort to make situations (experiences) and people more comprehensible. This involves reviewing and reliving the experience to bring it into focus (Bolton 2010).

Reflection is a process of exploring our experiences in order to learn from them acknowledging that much of what we know and how we know it comes from our everyday lives (Jasper 2007). Reflective learning involves deliberate cognitive processes that we use to explore an experience for what we can learn from it.

It can be seen from the above definitions that reflection is a personal process, and involves the movement away from acceptance of information, which novices (students) do, to questioning and critically thinking and learning (Wigens 2006). The outcome of reflection is a changed conceptual perspective or learning. It can take place in isolation or with others.

Scanlon and Chernomas (1997 – cited in Wigens 2006) suggest a three-stage model of reflection. Their first stage is awareness, in which reflection is initiated because the practitioner experiences discomfort about a situation or lacks information about it and wants an explanation. The second stage is critical analysis, which takes into account the practitioner’s current knowledge when the practitioner critically examines and thinks about the event or issue. The third stage is a new perspective that is the outcome of analysis in stage 2. This leads to changes in behaviour. In this model the emphasis is on the connection between critical thinking and reflection.

Wigens (2006) states that reflection involves making a judgement of the experience and assessments in the light of previous personal experience, or based on someone else’s experience. This leads to a decision being made. Undertaking reflection requires an ability to determine an endpoint so that reflection is practical and can be managed.

Jasper (2007) acknowledges that reflection is not always a comfortable or stress-free process. She states that it may force us to hold a mirror to ourselves and look at an image that we do not particularly like. But, as Jasper states, the processes are there to help us learn, move forward and develop.

Schön (1992) distinguishes between two types of reflection: reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action.

Reflection-on-action occurs after the event or situation and so contributes to the continuing development of skills, knowledge and future practice. It is the retrospective analysis and interpretation of practice in order to uncover the knowledge used, and feelings about, a particular situation. The practitioner may speculate on how the situation might have been handled differently, and what other knowledge would have been helpful.

Reflection-in-action occurs while practising and therefore influences the decisions made and the care given at that time (Atkins and Murphy 1993). It is the process whereby the practitioner recognises a new situation or problem and thinks about it while still acting. Although the issues may not be the same as on previous occasions, the skilled practitioner is able to select and remix responses from these previous experiences, when deciding how to solve this particular problem in practice.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree