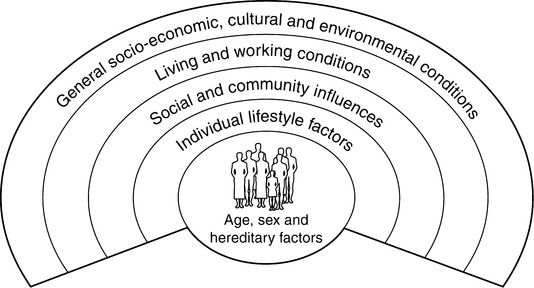

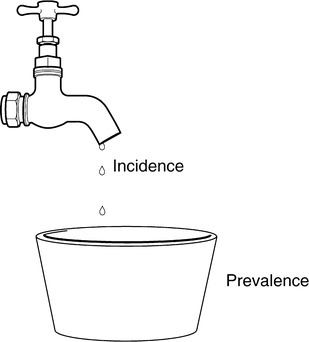

‘Public health’ is one of those terms that sometimes defies definition, and as such then takes on an aura of mystique, where practitioners are those initiated into the secret rites of the cult. The definitions put forward in recent years do not seem to do much to demystify what public health actually is. One of the more widely spread definitions of public health is: ‘the science and art of presenting disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organised efforts of society’ (Acheson 1988). The US government defines public health as ‘what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy’ (Centers for Disease Control 1999). These definitions, when unpicked, show ‘public health’ to be all those activities aimed at securing and promoting the health of a population that are the collective responsibility of some social organisation, for example the state or government. Our understanding of public health becomes clearer when we explore what types of functions or activities are covered under the rubric of public health, as we will see below. Public health came into its own in the nineteenth century, when European and North American countries were undergoing rapid industrialisation, which brought with it both great wealth and great misery. Social reformers concerned themselves with the conditions of both workers and the destitute, and began to look at how to make changes in people’s social, economic and environmental conditions as part of improving living conditions and well-being overall. Primary amongst these reformers was Edwin Chadwick, Secretary to the Poor Law Commission, whose Report on an Enquiry into the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain (Chadwick 1843) galvanised the social conscience of the middle classes of the day, and led to eventual changes in law to the advantage of those living in poverty. John Snow’s powers of observation during a cholera epidemic in London in 1848 led to the first technical health protection intervention – the removal of the Broad Street pump from the source of cholera-contaminated water. Public health activists throughout the nineteenth century focused primarily on social and environmental conditions that impacted on health, and paved the way to major improvement in population health more generally through a reduction in infectious diseases. During most of the 1800s health care workers had little idea of what actually caused the diseases they were treating, as Box 3.1 illustrates. (Most continued to operate under the ‘miasma’ theory, that ‘bad’ air and ‘bad’ water were to blame – not completely without reason.) It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century with the invention of the microscope and the identification of the first bacteria that ‘germ theory’ was born and action began to shift away from improving living conditions to developing medicines to prevent and treat diseases. ‘Miasmists’ aligned themselves with social radicals who continued to push for social reform as the best way to improve health and living conditions. ‘Contagionists’ were more politically conservative and pushed for medical solutions to health problems (Young 1999). Public health may also be understood through an analysis of the determinants of health. Several models of health determinants have been put forward. One of the most commonly used is shown here in Figure 3.1, developed by Dahlgren and Whitehead in 1991. The factors influencing health are multiple and multi-level, as indicated by Figure 3.1. While individual factors, such as age, gender and genetic make-up create a predisposition to good or poor health, wider determinants of health have been shown to be as, or more, important in dictating an individual’s or community’s health status. The UK House of Commons Select Committee Report (2000) provides greater detail of the wider determinants, taken from the Public Health Green Paper Reducing Health Inequalities: An Action Report: Midwives have an honourable tradition themselves in the public health arena. The health promotion work training women in ‘mothering skills’ carried out by midwives and health visitors in the first half of the twentieth century helped lead to a radical drop in infant mortality rates, from 150 per 1000 in 1900 to 55 per 1000 in 1940 (Williams et al 1994). One important area of public health is being able to assess the degree of a particular problem by measuring its extent in a population. The main aspect of a midwife’s role is ensuring a positive outcome to pregnancy, measured through the health of mothers and their infants. Throughout the world numerous initiatives have been developed to tackle the problem of poor pregnancy outcomes and high infant death rates. In the 1960s the World Health Organization (WHO) reported its concerns about the much higher rates of mother and child mortality in developing countries. Its 1969 Expert Committee Report found that high mortality in both mothers and their children were caused mainly by poor nutrition and widespread infection, as well as dangerous and excessive childbearing related to poor access to health services (WHO 1992). The difference between incidence and prevalence can be understood as follows: incidence is about ‘becoming’ while prevalence is about ‘being’ (see Fig. 3.2). An example of this, when discussing pregnancy, is that the incidence of pregnancy = the number of women who become pregnant during a specific time period vs the number of women who are pregnant during a specific time period. Women who already are pregnant would not be included in the denominator for the incidence rate; they are not at risk of becoming pregnant since they already are pregnant! A maternal death can be defined as: ‘the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, regardless of the site or duration of pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management’ (WHO 1999:9). This same WHO document goes on to identify two main types of maternal death: direct or indirect obstetric death. Direct obstetric death is any death arising from complications of pregnancy, labour or the postpartum period, usually due to haemorrhage, sepsis, eclampsia, obstructed labour or the complications of unsafe abortion. Other causes of direct obstetric death include dangerous obstetric interventions, omissions or incorrect treatment (WHO 1999). Indirect obstetric deaths result from pre-existing conditions, or conditions that arise as a result of the pregnancy (e.g. diabetes, malaria, HIV/AIDS, cardio-vascular disease). Lifetime risk of maternal death is estimated by multiplying the maternal mortality rate by the length of the reproductive period (average around 35 years). This allows planners to review both the probability of becoming pregnant and the probability of dying as a result of pregnancy, cumulated across a woman’s reproductive years. Another way of calculating the lifetime risk of maternal death is by multiplying the total fertility rate by the maternal mortality rate. The total fertility rate can be calculated by taking the sum of the age-specific fertility rates for women of child-bearing age (15-49), as explained in Box 3.2. There are numerous direct causes of maternal death, and these too differ between developed and developing countries. The pie charts (Figs 3.3 and 3.4) illustrate the main direct causes of maternal death, comparing the global picture and the UK.

Expanding horizons: developing a public health perspective in midwifery

UNDERSTANDING PUBLIC HEALTH

Fixed:

Genes, sex, ageing

Social and Economic:

Poverty, employment, social exclusion

Environment:

Air quality, housing, water quality, social environment

Lifestyle:

Diet, physical activity, smoking, alcohol, sexual behaviour, drugs

Access to services:

Education, National Health Service, social services, transport, leisure

MEASURING MATERNAL HEALTH

Age-specific death rate

Lifetime risk of maternal death

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Expanding horizons: developing a public health perspective in midwifery

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access