Chapter 8 Evidence-based practice

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

describe the need for evidence-based practice and the links between research, practical experience, and evidence-based practice or policy

describe the need for evidence-based practice and the links between research, practical experience, and evidence-based practice or policyThe evolution: evidence-based medicine

In 1972, an epidemiologist from the UK, Dr Archie Cochrane, criticised the medical profession for not providing reviews of clinical interventions so that policy-makers and organisations could base their practice on empirically proven evidence (Killoran & Kelly 2010; Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2005; Oliver & McDaid 2002).

Similarly, researchers from McMaster University in Canada felt the medical profession were relying on clinical experience and personal judgement, rather than empirically supported evidence (Hamer 2005). It was this group of researchers who first coined the term ‘evidence-based medicine’, which they defined as ‘the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients’ (Sackett et al. 1996 p 71). This definition implies an organised process applied to a particular circumstance and recognises the clinicians’ expertise. Conscientious use of evidence implies a systematic and organised approach to the identification of the evidence. Judicious use implies the wise application of the evidence to the particular clinical circumstances and recognises the value and importance of the clinician’s cumulative experience, education and skills in applying the evidence to the particulars of the patient.

In 1993, the Cochrane Collaboration was launched, which aimed to provide up-to-date systematic reviews of health care interventions, and to ensure the accessibility of these reviews by the public globally, so that consumers could make informed decisions about their health care (Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2005) (Box 8.1).

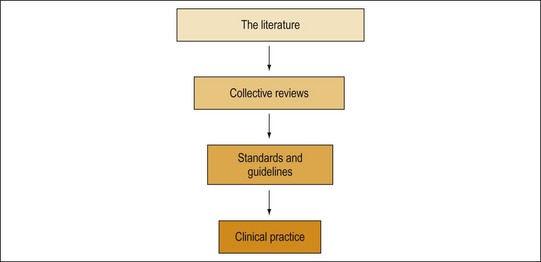

The impact of evidence-based medicine has been, first, to encourage and develop the means of accumulating the evidence in a systematic manner, analysing the evidence and converting that evidence into clinical pathways, and clinical guideline standards, which translate the often enormous quantities of data available in the literature into an accessible and usable format for clinicians. Figure 8.1 demonstrates that process for the development of clinical guidelines.

Second, an emphasis on evidence-based medicine has served to reduce the previous reliance on ‘opinion’ as unqualified ‘evidence’ in its own right. Naidoo and Wills (2005) present four ways in which decisions have been made, including:

Recently, the term has been broadened to evidence-based practice in an effort to spread the concept to all health professionals. The principles have been applied to public health, health policy, health planning and health management (Gerrish 2006).

The nature of evidence and key concepts of evidence-based practice

We are currently living in an ‘information age’ (Hamer 2005; Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2005). Technological advancement means increased accessibility to information (Hamer 2005). As an example, the Internet brings information from all over the world into our homes. Information is literally at our fingertips.

Activity

Reflection

There is a range of sources of information, including journals, textbooks, newspapers, health magazines, editorials, Internet newspapers, news on our mobile phones, lifestyle magazines, Australian telecommunications industry/association’s reports and websites, Internet blog (opinion) sites run by companies or individuals, and government and private health agencies’ websites and reports. Some information sources are more trustworthy than others. Information that is provided by the Internet or in news clips may not be as reliable as information that is provided by rigorous scientific studies. There has been a significant increase in the number of research studies being conducted, research papers being published and the number of research journals available. Technological advancements have meant that the quality of research methodologies has improved, and research findings are more easily accessed and readily available (Hamer 2005; Killoran & Kelly 2010).

While we are lucky to have so much more information at our disposal, it does mean that there is more information to sift through to determine what constitutes evidence. In short, information must be sorted, analysed and then given meaning, or moulded into knowledge by describing its practical application in specific settings (Dawes 2005).

This process can be very time consuming. In addition, there are other factors that add to the complexity of identifying and implementing ‘best practice’, including problems with dissemination and communication of the implications of research, and the methods employed to obtain these results (Courtney 2005). Political pressure might influence what research is conducted, published and used to influence practice, and organisational barriers might hinder health professionals who are implementing EBPs within their organisations.

The nature and scope of knowledge

Underpinning the quest for evidence are questions about the nature of knowledge. This is termed ‘epistemology’ (Topping 2006). Epistemology is the branch of Western philosophy that is concerned with reality – that is, the nature and scope of knowledge and how it is produced (Topping 2006). Over the course of human history, different perspectives of reality have dominated. These dominant perspectives or ‘world views’ are referred to as ‘paradigms’. A change in the dominant perspective is referred to as a ‘paradigm shift’ (Taylor & Roberts 2006).

Professional groups may have different paradigms. What constitutes evidence for one professional group may not be considered so for another profession. Even within health care and health research, individuals may adhere to different perspectives (Rychetnik & Wise 2004; Taylor & Roberts 2006), and have different views about what forms sound knowledge. Knowledge and evidence are, therefore, socially constructed.

Research is influenced by assumptions underlying the current paradigm of the profession and individual researchers, and is not an isolated or objective process (Topping 2006). Using ‘rigorous’ research to guide practice is a requirement of the current scientific paradigm. Corcoran and Vandiver (2004) claim that this approach is now considered the industry standard. Where ‘well-established’ practices would have once constituted ‘evidence’, contemporary EBP requires that the efficacy of the intervention is demonstrated in practice (Frommer & Rychetnik 2003 p 60).

The concept of ‘rigor’ and the methods required for rigorous research are also socially constructed, influenced by the researchers’ ‘worldviews’. Traditionally, science has taken a positivist approach, believing in absolute and objective truths (Topping 2006). Positivists are concerned about the frequency and distribution of an event or phenomenon, and attempt to use standardised methods and maintain objectivity, primarily through distancing themselves from the subjects under study, to reach a ‘truth’ (Liamputtong & Ezzy 2005).

However, there has been a growing trend in health research to use qualitative methods. While there are a number of different qualitative approaches, researchers in this field recognise that in order to understand human behaviour we must gain an understanding of the feelings, values, perspectives and interpretations of individuals and social groups. Qualitative research aims to provide an in-depth, information-rich account of human experience. Qualitative researchers argue that reality is not objective; rather it is socially constructed. Therefore, there is no single truth (Topping 2006).

The activity on this page should show you how the research process is influenced by the worldview we hold. The perspectives of both the individual researcher, the science, and health professions will influence how research is carried out and what is established as ‘evidence’. The shift of focus away from quantitative methods to utilising a combination of methods is an example of a paradigm shift (Brownson et al. 2009; Taylor & Roberts 2006; Topping 2006). Many health researchers argue that using a combination of perspectives and methods can provide a more comprehensive account of the phenomenon under study, and that different methods may be more useful for answering different questions (Topping 2006).

Activity

Key concepts of evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice was born among a growing concern to improve health care and health outcomes by basing practice on the best available evidence (Gray 2009; Rosenthal & Sutcliffe 2002).

EBP should not be confused with ‘research utilisation’. Research utilisation refers to using knowledge gained from a single study (Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2005). While sometimes there may not be sufficient research on a particular topic to conduct a systematic review, there are dangers inherent in using the results of only one study to guide practice. Let us consider Case Study 8.1.

Case study 8.1 Dangers of ‘research utilisation’

Kraaijenhagen et al. (2000) reported that a study they had conducted revealed travellers were not at an increased risk from deep vein thrombosis (DVT) compared with the general population. Shortly after, other research studies reported that travellers were at increased risk. In 2001, Scurr et al. (2001 p 1485) reported ‘symptomless DVT might occur in up to 10% of long-haul airline travellers’. Public opinion was further persuaded by reports of a woman who was travelling by air to Australia and died from a pulmonary embolus.

According to Dawes (2005), several studies published over a 6-month period reported conflicting data. Consumers who sought advice from their general practitioner on the health risks of travelling may have received an incomplete picture of the risk, if the health care professional only relied on the first article published.

In some cases there will be no research available at all on a certain topic. In a practice setting it is not feasible to send a client away just because there has been no prior research conducted about his or her problem. Evidence-based practice must also take into consideration the expertise of the health professional, as well as the values and preferences of the client (Mazurek Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt 2005).

In practice, what does an evidence base mean? Is it about using strategies that the research suggests are the best means for achieving the stated aims? Is it about changing practice? Is it about a systematic appraisal of the best available evidence? The answer to all of these questions is yes. However, the process is never quite as simple as that. In practice, there is never absolute certainty, as programmes that are implemented even in similar circumstances are never quite the same. In addition, research is not always reliable and valid, even if it is available on a particular issue of concern, or if there is a reasonable amount of available research information. As Naidoo and Wills (2005) state, ‘evidence-based practice is more like a journey towards more effective practice and it is an approach that requires the practitioner to become more open-minded and flexible’ (Naidoo & Wills 2005 p 48) (Box 8.2).

What is evidence-based practice?

Activity

Identifying the evidence that relates to the problem is not as easy as it sounds. There are two major issues to be considered when thinking about the evidence that might suggest a particular way of approaching an intervention. The first is what sources should you be looking for as evidence and, second, how should you use evidence to make an informed decision? To answer the first question, most EBP relies on primary research from academic or professional journals, textbooks, published and unpublished reports, conference papers and presentations. The second question is about the range of evidence that might inform practice and that might include how effective the intervention was in meeting its goals, whether there is evidence available on the transferability of the intervention to other settings and with other populations, what the positive and negative effects of the intervention were and what the barriers to implementing the intervention were (Naidoo & Wills 2005).

The scientific model has gained prominence as a quantitatively objective method for finding the evidence, and contextual factors such as environment, socioeconomic factors or education are considered as ‘confounding variables’ and study designs often try to eliminate their effects. RCTs are viewed as the ‘gold standard’; however, where populations are concerned it becomes very difficult if not impossible to adopt an RCT methodology (Naidoo & Wills 2005 p 52). Following this scientific approach, research findings are graded according to an established ‘hierarchy of evidence’ (Table 8.1) according to how valid and reliable the methodology for the research is considered to be. For more detailed guidelines for reviewing and identify levels of evidence see the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) web site located at the end of this chapter.

TABLE 8.1 Hierarchy of evidence

| Type 1 evidence | Systematic reviews and meta-analyses including two or more RCTs |

| Type 2 evidence | Well-designed RCTs |

| Type 3 evidence | Well-designed controlled trials without randomisation |

| Type 4 evidence | Well-designed observational studies |

| Type 5 evidence | Expert opinion, expert panels, views of service users and carers |

(Source: Naidoo & Wills 2005)

Where do you think public health fits into this notion of a scientific paradigm? How useful is this paradigm when population health research does not fit neatly into an RCT? Does this mean that there is no evidence base for public health? A focus on scientific experimental evaluation would ignore a large body of emerging work related to public health in community settings and interventions (Killoran & Kelly 2010). Desirable methodological characteristics of research into the effectiveness of interventions include issues such as:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree