Chapter Three. Evidence-based practice

Key points

• Defining evidence-based practice in public health and health promotion

• Skills for evidence-based practice

– Finding the evidence

– Appraising the evidence

– Synthesizing the evidence

– Applying the evidence to practice

• Limitations to evidence-based practice

• Using evidence-based practice to determine cost effectiveness

• Putting evidence into practice

• Dilemmas about becoming an evidence-based practitioner

OVERVIEW

Evidence-based practice and policy have become the new mantra in health care. Yet there is no clear consensus about what defines the information that can be described as ‘evidence’, or how it should be used to drive changes in practice or policy. The traditional ‘hierarchy of evidence’ has very clear limitations when used to evaluate practice in areas such as policy change, community development or individual empowerment. This chapter outlines current thinking about evidence, the reasons for pursuing evidence-based practice and policy, and the skills practitioners need to acquire in order to become evidence-based. Evidence-based policy and practice are similar in many ways. Both are activities which take place in a complex context where other factors, such as custom, acceptability or ideology, may be more important than evidence in determining outcomes. This chapter focuses on evidence-based practice and the challenges this poses for practitioners. Many of the issues relating to evidence-based policy are discussed in Chapter 4 on policy. Specific dilemmas which arise when applying evidence-based practice to broad public health and health promotion goals are identified and discussed. This chapter concludes that evidence-based practice in health promotion and public health needs to go beyond the scientific medical model of evidence to include qualitative methodologies, process evaluation, and practitioners’ and users’ views. Evidence-based practice is a useful tool in the public health and health promotion kitbag, but it is not the only or overriding criterion of what is effective, ethical and sound good practice.

Introduction

Think of an example of your practice where you have changed what you do. Has this change been brought about by:

• policy and/or management imperatives

• colleagues’ advice

• technological advances

• cost

• evidence-based practice recommendations

• your own assessment and reflection

• users’ requests and feedback.

|

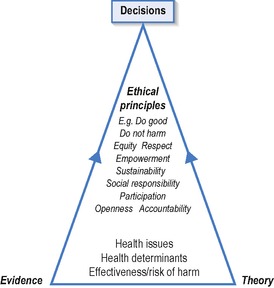

| Figure 3.1 • Influences on health promotion decision making (from Tannahill 2008). |

Other factors which affect current practice are tradition, management directives concerning policy targets, performance and service users’ views. Muir Gray (2001) argues that most healthcare decisions are opinion based and driven principally by values and available resources.

Evidence may refer to relevant facts that can be ascertained and verified. These facts may refer to incidence of disease; effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions and preventive services; the views of service providers and users.

Chapter 1 highlighted how good practice requires the use of explicit research evidence and non-research knowledge (tacit knowledge or accumulated wisdom). The process is uncertain and frequently no ‘correct’ decision exists, especially in the complex field of public health where there are few conclusive outcomes. Evidence-based practice (EBP) claims to provide an objective and rational basis for practice by evaluating available evidence about what works to determine current and future practice. It was first applied to medicine, when Sackett defined it as: ‘The conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about individual patients based on skills which allow the doctor to evaluate both personal experience and external evidence in a systematic and objective manner’ (Sackett et al 1996, p. 71). As such, it is clearly differentiated from:

• tradition (‘this is what we’ve always done’)

• practical experience and wisdom (‘in my experience, this approach is the most effective one’)

• values (‘this is what we should do’)

• economic considerations (‘this is what we can afford’).

Many professions have embraced the advantages of an evidence-based approach to decision making.

EBP offers the promise of maximizing expenditure by directing it to the most effective strategies and interventions. The exponential rise of information technology and almost instant access to a multitude of sources of information makes EBP a more realistic possibility. However, it is unrealistic to expect practitioners to track down and critically appraise research for all knowledge gaps. It can be difficult for individual practitioners to know what is happening in the research world and pre-searched, pre-appraised resources, such as what the systematic reviews of the Cochrane Collaboration can offer an already synthesized and aggregated overview of the most up-to-date research findings for the busy practitioner.

The opportunities for EBP may include:

• a current policy environment that values evidence

• links between service providers and universities to offer guidance and support

• new systems of clinical governance, audit and accountability that offer rigour and consistency in assessing outcomes

• greater emphasis on service users’ views and feedback

• education and training that prepares practitioners to be reflective, to critically appraise research findings, and to use and evaluate EBP

• multiprofessional working that encourages collective debate and consensus regarding EBP.

Barriers to EBP include:

• reliance on the dominant positivist scientific model of evidence that may undervalue alternative sources of evidence

• increased workload and expectations with limited time for reflection

• limited research data in non-medical, non-pharmacological areas

• patchy access to information services

• shortage of critical appraisal skills

• pre-existing targets and performance indicators.

Whilst policy makers and practitioners may have their own agendas, and practice may be determined by factors such as protectionism, self-interest or ideological commitments as well as resource constraints, EBP offers the attraction of being above these concerns and offering definitive and neutral answers as to what constitutes best practice.

The conventional approach to finding, reviewing and assessing evidence has been imported from medicine and clinical decision making. It has established a ‘gold standard’ of evidence that privileges systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Such reviews cover only a small proportion of public health issues, namely a small set of specific questions that can be answered by experimental methods, for example, do hip protectors reduce fractures from falls? As we have seen in our earlier book Foundations for Health Promotion (Naidoo and Wills 2009), and as we shall discuss further in Part 3 of this book, health outcomes are influenced by complex and interrelated factors. These include social, economic and environmental factors, as well as specific health-related behaviours, interacting with psychological, genetic and biological factors. Evidence that we may seek to guide public health and health promotion interventions is not always available – not because health promotion is ineffective but because of a paucity of evaluations. In order to understand ‘what works’ to improve health, we need to use evidence from a variety of sources, including qualitative and context-specific types of information or evidence.

Chapter 2 discussed how qualitative research is often denigrated as being ‘soft’, biased and not generalizable. However, there are accepted standards for rigour in qualitative research, and finding out about people’s perceptions, beliefs and attitudes is crucial to successful health promotion and public health interventions. Investigating the complex processes involved in health improvement programmes, or measuring a range of effects, including people’s views, provides vital knowledge for practitioners. Such evidence may not conform to the scientific model, but does offer a more realistic and useful assessment of how in practice interventions lead to outcomes.

Types of evidence

‘Scared Straight’ is a programme in the USA that brings at-risk or already delinquent children, mainly boys, into prison to meet ‘lifers’. Inmates, the lifers themselves, the juvenile participants, their parents, prison governors, teachers and the general public were very positive about the programme in all studies, concluding that it should be continued. However, in a systematic review, seven good quality randomized control trials showed that the programme increased delinquency rates among the treatment group (Petrosino et al 2000 cited by Macintyre and Cummins 2001). Participants may not tell the same story as the outcome evaluation for many reasons, but their views on the process are valid and important data in their own right. Participants’ views on the appropriateness and accessibility of the programme are essential in deciding whether or not to adopt programmes. The ideal programme will be both effective in terms of achieving desired outcomes, and acceptable to participants.

As Davies et al (2000, p. 23) observe, ‘There is a tendency to think of evidence as something that is only generated by major pieces of research. In any policy area there is a great deal of critical evidence held in the minds of both front-line staff in departments, agencies and local authorities and those to whom the policy is directed’. This broader range of evidence from government advisers, experts and users needs to be included in decision making about health improvement. This more inclusive approach to evidence is advocated by many commentators and forums. For example, the 51st World Health Assembly urged all member states to ‘adopt an evidence-based approach to health promotion policy and practice, using the full range of quantitative and qualitative methodologies’ (WHA 1998).

What does it mean to be evidence based?

For the health practitioner, becoming evidence based means building practice on strategies which research has demonstrated are the most effective means for achieving stated aims. In theory, this would mean swapping uncertainties and traditional practices for specified techniques and strategies in the knowledge that they would lead to certain outcomes. In reality, there is never such absolute certainty, and research is not always totally reliable and valid, even if it is available for the particular issue of concern. So EBP is a journey towards more reliable and effective practice, and one that involves the practitioner becoming open-minded and flexible. To become evidence based, one has to be willing to change one’s practice. This refers to organizations as well as individuals or professions. Individual practitioners’ attempts to become more evidence based may flounder due to organizations’ entrenched practices and inability to change.

Decision making in public health and health promotion demands information or evidence about the nature of the problem to be addressed, including its magnitude and whom it affects, as well as evidence about possible interventions. When considering the evidence that has been ‘tested’ in an intervention practitioners need to know:

• does it improve health, that is, is it effective?

• is it cost effective compared to other interventions or doing nothing, that is, is it efficient?

• is it acceptable to users or the public?

• can it be implemented safely, consistently, and feasibly and will it strengthen practice?

• will it tackle injustice and contribute to reducing inequalities?

I work in Southern Africa and we need to find ways of reducing HIV transmission and continue to promote the condom. One company offered to supply us with female condoms but rather than just go ahead and distribute them on an ad hoc basis we wanted to know if there was any evidence supporting the use of the female condom in Africa. In particular, we wanted to know:

• How many women use female condoms?

• What are their experiences and what would be the barriers to their acceptability?

• What are the sociocultural issues influencing acceptability in African contexts?

• How have they been implemented in other health settings?

• Would there be political support within our sexual health strategy for the promotion of the female condom?

We did a simple internet search and found lots of scholarly papers but they reported information from African American women in the USA or STD clinic users which didn’t seem relevant. One person had reported at the 2004 AIDS conference in Bangkok about a programme distributing female condoms in a district. We did find one paper in the South African Medical Journal (Beksinska et al 2001) but we could only read the summary online and so don’t know whether this study is relevant or comprehensive.

Commentary

This practitioner had access to the internet and search skills both of which often constitute barriers to EBP. The access for full text papers is limited for most practitioners especially in low-income countries. Most evidence on the female condom relates to its effectiveness in reducing STI transmission and not its acceptability.

Many public health and health promotion interventions have been introduced without good evidence that their outcomes meet stated objectives. For example, breakfast clubs in schools have been widely introduced and promoted as part of a drive to improve healthy eating and to tackle inequalities in child health. Evaluation shows that they provide children with a nutritional start to the day, can therefore improve concentration and performance, and promote social interaction. However, there is only limited evidence of their effectiveness in promoting healthy eating amongst children, or of their ability to target the most disadvantaged children (Lucas 2003).

It is this uncertainty that has led to the production of evidence-based briefings that appraise current evidence of effective interventions in a digestible form for practitioners and policy makers. Evidence-based briefings select recent, good quality, systematic reviews and meta-analyses and synthesize the results. Clinical guidelines are a top-down strategy to produce practice in line with available evidence of what works and to ensure comparable standards and reduce variations in practice. Clinical guidelines translate evidence into recommendations for clinical practice and appropriate health care that can be implemented in a variety of settings. Recommendations are graded according to the strength of the evidence and their feasibility. So recommendations supported by consistent findings from RCTs that use available techniques and expertise would be graded more highly than recommendations supported by an expert panel consensus that rely on scarce expertise and resources. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) publishes guidance on public health interventions (see www.nice.org.uk/guidance/PHG/published.) Such guidance makes recommendations for populations and individuals on activities, policies and strategies that can help prevent disease or improve health. The guidance may focus on a particular topic (such as smoking), a particular population (such as schoolchildren) or a particular setting (such as the workplace).

Health promotion and public health practitioners face particular difficulties in becoming more evidence based. These include:

• the complexities of searching for primary studies which are sparse

• assessing evidence from non-randomized studies (including qualitative research)

• finding evidence relating to process and how an intervention works

• synthesizing evidence from different study designs

• transferability of results to other contexts which differ from those used in the original research.

Skills for EBP

Adopting an evidence-based approach follows five key stages:

• turning a knowledge gap into an answerable question

• searching for relevant evidence

• extracting data/information for analysis

• appraising the quality of the information/data

• synthesizing appraised information/data.

Being evidence based means having both the knowledge and the confidence to tackle issues effectively. To become an evidence-based practitioner means adopting a critical view with regards to research and evidence, and being willing to change your practice if the evidence suggests this is worthwhile. The practitioner who seeks to become evidence based needs to acquire the knowledge and skills to find out and access, critically appraise, and synthesize and apply relevant evidence. Evidence includes research as well as more anecdotal and developmental accounts linking inputs to outputs.

Being evidence based includes the ability to separate evidence from other drivers of practice, including politics, custom and ethical considerations. Above all, being evidence based requires an open and critical mind to reflect on your own knowledge about an issue, and assess competing claims of knowledge. Many interventions are implemented despite a lack of certainty about the evidence for their effectiveness because practitioners act on intuition or respond to pressures to do something. Cummins and Macintyre (2002) refer to ‘factoids’ – assumptions that get reported and repeated so often that they become accepted. They describe the way in which food deserts (areas of deprivation where families have difficulty accessing affordable, healthy food) have become an accepted part of policy because they fit with the prevailing ideological approach, although there is little evidence to support their existence. Equally, some interventions are not implemented despite evidence of their effectiveness because they are not politically or socially acceptable.

Asking the right question

There are now many ‘short-cuts’ to evidence in systematic reviews, evidence briefings and guidance but knowledge gaps remain. For example, NICE recently published guidance on promoting physical activity for children and young people (NICE 2009) but there was little evidence on what works to promote activity in pre-school children. Being clear about what you need to know is a vital first step. It is this process that starts the search for relevant evidence and the process of appraisal. Asking the right question means finding a balance between being too specific (asking a question that is unlikely ever to have been researched), and being too vague (asking a question that will produce a mass of research studies, many of which will be inapplicable to the context and circumstances you are interested in).

A smoking cessation coordinator is concerned at the rising rates of smoking among young women. The coordinator wants to extend the service to young people who wish to quit. The coordinator thinks that a cessation group could be established in one of the local secondary schools but is not sure how to proceed or whether the accepted model of cessation would work with young people. What does she need to know?

The coordinator will be interested in those factors that facilitate young people to quit and the factors that might act as barriers. The coordinator will search for research on the impact of the school setting on smoking, smoking cessation interventions in schools and its efficiency in relation to other methods such as health education and its acceptability to young women. If insufficient research is available, they may look at other research on young people’s attitudes to quitting and cessation studies in other settings.

What counts as evidence?

Evidence may be of many different types, ranging from systematic reviews and meta-analyses, to collective consensual views, to individual experiences and reflections. All types of evidence have their uses. EBP traditionally reifies science above experience but as we have seen in Chapter 1, experiential reflection is an important part of informed practice. Similarly, the expertise of users is vital to developing acceptable interventions. Most EBP relies on:

• written accounts of primary research in refereed academic and professional journals

• academic and professional texts (reviewed)

• independently published reports

• unpublished reports and conference papers and presentations (grey literature).

Evidence may be defined as data demonstrating that a certain input leads to a certain output. However, the use of evidence to inform practice is broader than this, and encompasses:

• information about an intervention’s effectiveness in meeting its goals

• information about how transferable this intervention is thought to be (to other settings and populations)

• information about the intervention’s positive and negative effects

• information about the intervention’s economic impact

• information about barriers to implementing the intervention (SAJPM 2000, p. 36, cited in McQueen 2001).

The scientific medical model has gained dominance in the debate about defining evidence. This model states that evidence is best determined through the use of scientific methodologies which prioritize quantitative objective fact finding. The use of scientific models of evidence leads to a search for specific inputs causing specific outputs, regardless of intervening or contextual factors such as socio-economic status, beliefs or a supportive environment. Such intervening factors, which mediate and moderate the effect of inputs, are viewed as ‘confounding variables’ and study designs try to eliminate their effect. The RCT, using the experimental method, is viewed as the most robust and useful method for achieving results which qualify as evidence and is viewed as the ‘gold standard’. The criteria relevant for RCTs include:

• The intervention is experimental, with a control group which does not experience the intervention.

• There is random allocation of individuals to the experimental or control group.

• Allocation is double-blind; that is, neither patients nor practitioners know which group is the experimental or control group.

• There is a baseline assessment of patients to ensure that the experimental and control groups do not differ in any significant ways.

• There is a full follow-up of all patients.

• Assessment of outcomes is objective and unbiased.

• Analysis is based on initial group allocation.

• The likelihood of findings arising by chance is assessed.

• The power of the study to detect a worthwhile effect is assessed.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access