Introduction

One of the guiding principles of pre-registration midwifery education is the requirement of knowledge and the use of best available evidence to inform practice. The Standards for Pre-registration Midwifery Education emphasise that this must be achieved through searching, analysing, critiquing the evidence and using it in practice. The need to change and adapt practice as well as disseminating research findings are key aspects of the student’s education (NMC, 2009) as well as being a focus in ongoing professional development of the midwife. Furthermore, the commitment in contemporary maternity policies to provide quality service within an evidence-based environment underscores the necessity for a cadre of midwives knowledgeable in both research and evidenced-based midwifery practice.

This chapter focuses on the midwife’s role in contributing to the development and evaluation of guidelines and policies to ensure the best care for women and babies. It will include a discussion on research and best available evidence concerning midwives, women and babies. The importance of the critical appraisal of knowledge and research evidence will be emphasised as well as keeping up to date with evidence, applying evidence to practice and the dissemination of new evidence to others. In particular, the chapter aims to address Domain IV of Standard 17 of Standards for Pre-registration Midwifery Education (NMC 2009). Domain IV relates to advancing quality care through evaluation and research. This is to be achieved by the application of relevant knowledge to the midwife’s own practice in structured ways which are capable of evaluation. This entails:

- a short reminder of some research methods that midwives might encounter that are relevant to their practice

- a discussion of best available evidence

- steps involved in searching the literature

- hierarchy of evidence

- appraising the literature

- guidelines in midwifery practice.

Research methods

The purpose of research is to increase the body of knowledge available to practitioners, consumers, managers, economists and educationalists. It is a systematic scientific approach characterised by (1) order and control, (2) empiricism, and (3) generalisation (Polit & Beck 2006). Research evidence can be viewed as a continuum, going from a purely qualitative perspective at one end to the purely quantitative at the other end. The methods used depend on the question(s) to be addressed. Several classifications of research methods are available, e.g. quantitative or qualitative, prospective or retrospective, descriptive, exploratory or explanatory, phenomenology or positivism, holistic or reductionist, to cite but a few.

Research methods situated at the more qualitative or phenomenological end of the research continuum are more likely to be associated with the social sciences because the questions they answer are based on an assumption that the world in which events occur is socially constructed. This type of research does not aim to test a hypothesis, but rather to generate one based on the understanding of the values and meanings of observed phenomena, from the perspective of participants. Qualitative research approaches typically include methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, case studies, non-participant observations and ethnography.

At the other end of the continuum, quantitative or positivist research methods are based in the natural sciences, and aim to test a stated hypothesis. This area of research is reductionist rather than holistic, e.g. measuring the level of cortisol in the presence of stress but not how the individual experiences/feels about stress which would be addressed via a more holistic qualitative approach. Hypothesis testing will be based on empirical, objective and measured observations. Measurements will be statistically tested so that the initial hypothesis can be either supported or rejected. This type of research is concerned with the testing of cause-and-effect relationships, or at least correlations.

Each research method has its own specific aims, characteristics, strengths and limitations. Numerous textbooks on research methods exist. Many have been written more specifically for different professional groups, e.g. nurses, doctors or psychologists, but the principles are the same whatever the discipline for which they are intended. We turn now to exploring best evidence followed by appraisal of research evidence.

Best available evidence

The student may begin by asking: What is meant by best available evidence to inform practice? Given that practice should be informed by evidence, evidence-based practice is one in which the midwife’s approach to decision making incorporates a number of factors such as the best evidence that is available (which may or may not be research based), that is appropriate and includes the patient’s views as well as clinical expertise about the topic under review.

Three definitions of evidence-based practice are provided below: Sackett et al.’s (1996, pp71–72) frequently cited definition of evidence-based practice is from a medical perspective and states that evidence-based practice is:

… the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research … and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care.

DiCenso’s (2003, pp21–22) definition is from a non-medical point of view and is applicable to midwifery.

“Best research evidence” refers to methodologically sound, clinically relevant research about the effectiveness and safety of nursing (and midwifery) interventions, the accuracy and precision of nursing assessment measures, the power of prognostic indicators, the strength of causal relationships, the cost-effectiveness of nursing (and midwifery) interventions and the meaning of illness or patient experiences. Research evidence alone, however, is never sufficient to make a clinical decision. As nurses (and midwives), we must always trade the benefits and risks, inconvenience and costs associated with alternative management strategies, and in doing so consider the patient’s values.

A less rigid definition of evidence-based practice is offered by Muir Gray (1997, p9) who suggests that it is:

… an approach to decision making in which the clinician uses the best evidence available, in consultation with the patient, to decide upon the option which suits the patient best.

You will note that the definitions give attention to the patient’s views in the decision-making process. Further, the emphasis on systematic research as the best quality evidence may not always be available. There may be areas in midwifery practice which remain under-researched. For example, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a method of pain relief that has been used in childbirth since the 1970s. The precise physiological mechanisms whereby TENS relieves pain are not well understood but some women have used it on more than one occasion. There is a paucity of methodologically robust evidence on which to provide women with informed choices but nevertheless it is used based on experience in practice. Thus the ‘best available evidence’ may not always be research based in that it has been subjected to the rigours of systematic research. Midwives need to be aware that the type of evidence they may need to integrate into their practice may prove to be difficult and time consuming to find. It is, however, an essential skill to have in order to implement evidence to improve practice. Furthermore, midwives will be expected to present the evidence on which their decision was based. In an economic climate where cost-effectiveness is a factor in resource allocation, the midwife will have to find and apply the best available evidence for women and babies in their care.

An important consideration for evidence-based practice is the culture of the organisation (Offredy et al. 2009). Parahoo (2000) suggests that organisational characteristics of healthcare settings are overwhelmingly the most significant barriers to research use among nurses. These views include whether or not the organisation is a learning one with a memory (Offredy et al. 2009), which encourages continuing education of staff, thus valuing people, or one with low staff morale and low regard for individuals. Thus organisational support is crucial if midwives are to be proactive in extending the boundaries of care.

Sackett et al.’s (1996) definition of evidence-based practice has meant that there has been a tendency to view ‘evidence’ in terms of quantitative research such as randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews. Potts et al. (2006) acknowledge the importance of randomised controlled trials whilst stating that evidence that may be used to improve maternity and child care will come from a variety of sources as some of the issues encountered in practice are not always quantifiable, for example, women’s experience of being in labour, the effects of treatment or choice of treatment. Thus, the type of evidence used will depend on the clinical situation, the question to be answered and the type of decision being made.

To be able to adopt an evidence-based approach to practice, midwives must ensure that they understand how to appraise the quality of the evidence presented in published work and decide if research findings should or should not be implemented. The next section provides a step approach to searching the literature followed by appraisal of the literature.

Steps in searching the literature

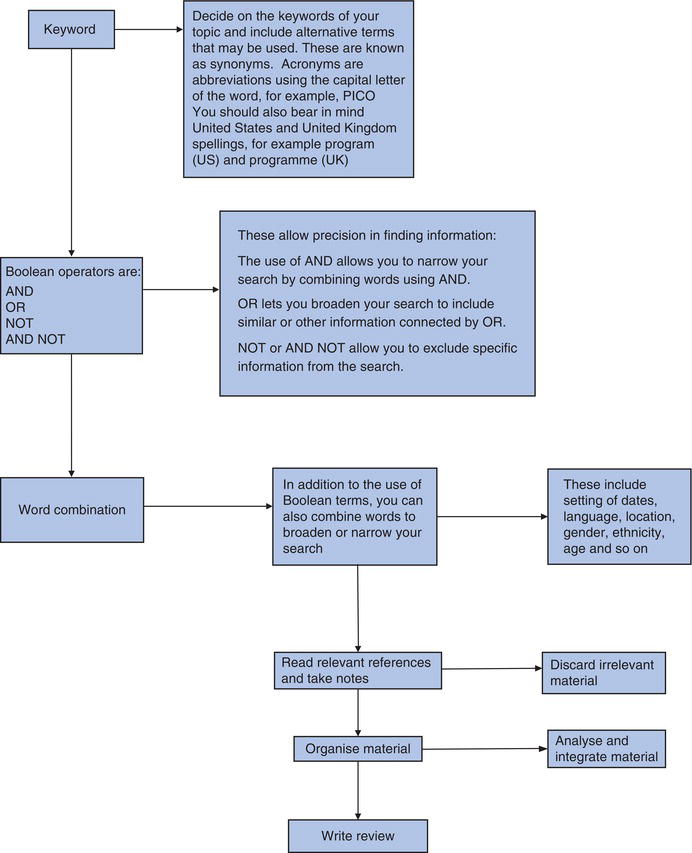

The flow diagram in Figure 18.1 takes you through the steps you need to undertake in order to identify and obtain the relevant literature.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are characteristics which are essential to the problem under scrutiny (Polit & Beck 2008). They are sometimes referred to as eligibility criteria; in other words, the sample population must possess the characteristics. Examples of inclusion or eligibility criteria are:

- age groups (for example, you may wish to have inclusion criteria for primigravida women aged 25–35 years of age to compare their experiences of labour)

- language (for example, English)

- location (for example, France, United States or a local area)

- date/time period (for example 2010–2013)

- (possibly) evidence-based medicine.

The inclusion criterion of evidence-based medicine will mean that the results of the search will be limited to articles reviewed in databases such as Health Technology Assessment (HTA), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) and Databases of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE). DARE complements the CDSR by providing a selection of quality-assessed reviews in those areas where there is currently no Cochrane review (Polit & Beck 2008).

Figure 18.1 Steps in the literature search. Adapted from Hart 1998; Burns & Grove 2007; Polit & Beck 2008.

Table 18.1 Hierarchy of evidence

| Level | Evidence |

| 1 | Systematic reviews/meta-analyses |

| Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) Experimental designs | |

| 2 | Cohort control studies Case–control studies |

| 3 | Consensus conference |

| Expert opinion | |

| Observational study | |

| Other types of study, e.g. interviews, local audits | |

| Quasi-experimental, qualitative design | |

| 4 | Personal communication, expert opinion |

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria are characteristics that you specifically do not wish to include in your search, such as multigravida if the problem pertains to primigravida with diabetes. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are important characteristics of a research study as they have implications for both the interpretation and generalisability of the findings (Polit & Beck 2008).

Having obtained the literature, you will need to decide on the worth of the material found. This can be done by assessing the information by using a hierarchy of evidence (Table 18.1) or by reviewing the literature using the research process.

Appraising the literature

Reviewing or appraising the literature requires developing a complex set of skills acquired through practice. A comprehensive review of the literature is important because it:

- provides an up-to-date understanding of the topic and its significance to midwifery practice

- identifies the methods used in the research

- helps in the identification of significant controversies

- identifies inconsistencies in findings relating to your area of midwifery practice

- helps in the formulation of research topics, questions and direction

- sharpens your ability to identify and peruse the relevant literature efficiently and effectively

- enhances your ability to apply analytical principles in identifying unbiased and valid research in midwifery practice

- provides a basis on which the subsequent research findings can be compared.

A key principle when appraising research is to have a structured, systematic approach. It is useful to keep a record of how the review is conducted to ensure that the strategy is explicit, thorough/comprehensive, transparent and avoids replication and/or omission of references.

Before you begin your search, you should have a well-structured question: what is it that you would like to find out about? This will give a guide as to the type of research methods you may wish to explore.

Writers such as Burns & Grove (2003), Grbich (1999) and Polit & Beck (2008) suggest that a review of the literature can be divided into several sections. The subdivisions discussed below are an adaptation of the ideas and writings from these authors.

The structure of the report

Is the organisation of the report logical? Does it make sense/is it understandable? Does the report follow the sequence of steps of the process of research, such as these?:

- Introduction

- Identification of the research problem

- Planning of the research study

- Data collection methods

- Data analysis methods

- Discussion of the study and its results

- Conclusions obtained from the study

- Recommendation as a result of the findings from the study.

The organisation of the report may vary, but in all cases it should be logical. It should begin with a clear identification of what is to be studied and how, and should end with a summary or conclusion recommending further study or application. Different journals may require a different layout, but the key issue is a logical progression. As a general rule, a research report should comprise the following.

The abstract

The abstract of a research paper provides a summary of the question and the most important findings of the study. It outlines how these differ from those of previous studies and gives some indication of the methodology undertaken. It is usually about 200–300 words long, depending on the guidelines for specific journals and the thesis format of the relevant university. The abstract provides the reader with an overview of what the research has found. It is the first part of a paper that is read and if it does not include the relevant information that is being sought, it is unlikely that the remainder of the paper will be read as it may not be relevant to the reader.

Does the abstract, in a concise paragraph, describe:

- what was studied?

- how it was studied?

- how the sample was selected?

- how the data were analysed?

- the main findings of the research?

The introduction

The introduction serves to explain ‘why’ and ‘how’ the research problem was defined in a particular way. It should include the rationale for undertaking the research. It should also review critically the previous literature that the researcher has reviewed, pointing out any limitations in findings, methodology or theoretical interpretation. In addition, it provides a pathway to the methodology section by clarifying the need for research to be undertaken in the chosen topic, especially with regard to the methodological orientation or techniques chosen by the researcher.

The problem statement/purpose of the research

The introduction should be followed by a statement and discussion of the problem the researcher has investigated in the study. In this section you should consider whether:

- the general problem has been introduced and stated promptly

- the problem under investigation has been supported by evidence with adequate discussion of the background to the problem and the need for the study

- the general problem has been narrowed down to a specific research problem or to a problem that contains relevant sub-problems as appropriate

- if it is an experimental quantitative research study, the hypothesis directly answers the research problem

- if it is any other type of research study, that the research question directly addresses the problem identified.

The literature review and theoretical rationale for the study

This subsection relates to your own literature review. In a review of previous literature (including a theoretical rationale for the study to take place) you should aim to consider whether this section is relevant, clearly written, well organised and up to date and whether the reliability of the methods and data collection has been addressed. Your reasons should be substantiated.

- Was there a sufficient review of the literature and theoretical rationale associated with the previous research to assure you that the authors considered a broad spectrum of all the possibilities there were for investigating the present research problem?

- Is it clear how the study will extend previous research findings?