CHAPTER 1 Evidence-based nursing practice

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

1.3 What is ‘evidence-based practice’?

This is an example of evidence that can identify the cause of a disease and the effectiveness of an intervention to improve patient outcomes and decrease illness and disability.

The development of EBP can be traced back to the work of a group of researchers at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada, who set out to redefine the practice of medicine to improve the usability of information (Lockett 1997).

The term ‘evidence-based practice’, or EBP, has been derived from the earlier work of evidence-based medicine. Earlier years saw the development of EBP limited to the discourse of ‘medicine’; however, more recently many other health professional groups have moved to use EBP principles in their practice—for example, orthodontics (Harrison 2000) and allied health therapies (Bury & Mead 1998).

In 1997, Sackett et al (1997:2) published the first textbook on evidence-based medicine and defined it as:

In 2000, Sackett et al (2000) also included patient values as well as clinical expertise:

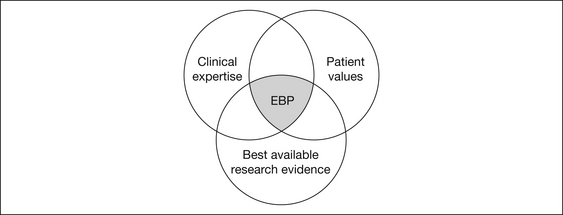

Critics of EBP have described it as ‘cookbook’ healthcare, or the worship of science above human experience. However, these criticisms are easily defused by an understanding of the three-factor interaction that EBP promotes: the best available research evidence; clinical expertise; and patient values (see Fig 1.1).

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) has been committed to publishing ‘Users’ guides’ to the research literature, with an excellent series of 25 articles on the topic published from 1993 to 2000. An important resource is a compendium of these articles, with further commentary, published in book form in 2002 (Guyatt & Rennie 2002). Although the guides are aimed primarily at a medical audience, they are highly appropriate for all health practitioners, including not only traditional quantitative/epidemiological approaches but also guides to interpreting qualitative evidence for practice (Giacomini & Cook 2000a, 2000b).

Therefore, EBP is not only applying research-based evidence to assist in making decisions about the healthcare of patients, but rather extends to identifying knowledge gaps, and finding, systematically appraising and condensing the evidence to assist clinical expertise, rather than replace it (Elshaug et al 2009).

1.4 What are the benefits of evidence-based practice?

1.5 What are the alternatives to evidence-based practice?

However, at times our comfort zone is challenged, and we identify a knowledge deficit when confronting an unusual or challenging problem. At times like these, practitioners may guide their practice by asking the opinion of colleagues or senior practitioners, reviewing employer policies, reading textbooks or lecture notes, leafing through nursing or other journals, and listening to speakers at professional conferences or other education forums. Can you think of some benefits and limitations to these methods of guiding practice? For example, if a decision needs to be made immediately, guidance from an experienced colleague or organisational manual provides a quick and easy reference tool. However, on the downside, even well-meaning and senior practitioners may not have the latest knowledge, and policy manuals are frequently out-of-date, even if they were prepared using the best evidence at the time of policy development.

1.6 Why the rapid spread of evidence-based practice?

Some of the major reasons cited by Sackett et al (1997) for the spread of the EBP movement have been the:

While it may be commendable to take the view that health departments have encouraged the development of EBP because they genuinely wish for patients to receive the best available care and to have the fewest adverse events possible, unfortunately, the reality may more likely be that ineffective care and adverse events are very costly in terms of extended lengths of stay in expensive hospital beds and require additional costs such as pharmaceuticals, pathology tests and radiography. Additionally, poor patient care and mistakes also lead to threats of litigation (Tarling & Crofts 2002).

1.7 Where is the evidence located?

1.7.1 CINAHL®

The CINAHL® (Cumulative Index to Nursing and the Allied Health Literature) database covers the nursing, allied health and health sciences literature from 1982 to the present. Originally a printed index, the CINAHL database has been available as a web-based product since 1994. CINAHL includes 1.7 million records and is growing weekly. Individuals can subscribe to CINAHL for a fee; however, as most health facilities and universities are subscribers, access is available free to their staff and students. Contact your librarian to find out whether your institution has CINAHL access (see www.ebscohost.com/cinahl).

1.7.2 MEDLINE®

MEDLINE® (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online) is compiled by the US National Library of Medicine and is acknowledged as the world’s most comprehensive source of bibliographic information for health. MEDLINE includes literature from the nursing, medicine and allied health disciplines, as well as the health humanities, and dentistry, veterinary, biological, physical and information science. MEDLINE has more than 17 million records dating from 1965 to the present and is updated weekly. Subscription through various commercial platforms is available for a fee to both individuals and institutions, and is widely available for free to staff and students of subscribing health facilities and universities. MEDLINE is also available free of charge from any computer connected to the internet through a platform called PubMed® (see www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed).

1.7.3 The Cochrane Library

Other materials include the Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR), the National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED) and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database. All residents of Australia can access the Cochrane Library for free online due to funding provided by the Commonwealth Government and administered by the National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS). Follow the link to the Cochrane Library at www.nhmrc.gov.au/nics.

1.7.4 PsycINFO®

The PsycINFO® database is the premier online collection of bibliographic references covering psychological literature from 1872 to the present, including articles from over 1300 journals. Most references include abstracts or content summaries. In addition to journal articles, many books, chapters and academic dissertations are included. PsycINFO is a fee-for-product service that is widely available at no charge to practitioners through subscribing health libraries (see www.apa.org/psycinfo).

1.7.5 Meditext

Further discussion on how to locate evidence is provided in Chapter 5, while Chapter 6 provides in-depth coverage on how to locate evidence when undertaking a systematic review.

1.7.6 The Joanna Briggs Institute

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) provides a database of evidence summaries (literature reviews) that review international literature on common healthcare interventions and activities. These summaries are linked to care bundles or procedures that describe and/or recommend practice. A database of systematic reviews, predominantly relevant to nursing and increasingly to allied health, is also located on the JBI website. These resources are available to subscribing members of the Institute. Many Australian healthcare facilities are members of the Institute and therefore provide free access to this information for their staff. Additionally, Best Practice information sheets—four-page summaries of results and recommendations for practice based on systematic reviews of research—are accessible free of charge (see www.joannabriggs.edu.au).

1.7.7 The ‘grey’ literature

The ‘grey’ literature is a term used to refer to evidence that exists in some format but is difficult to find due to its non-inclusion in searchable bibliographic indexes such as MEDLINE, which predominantly contain references to articles in highly ranked peer-refereed journals. While some grey literature may not be contained in such journals because it is of poor quality, this is not always the case, and a thorough literature search will also make efforts to identify relevant research that may have been published only in conference proceedings, non-refereed journals, government/organisational reports, textbooks or the popular press, as well as academic theses that may not have been followed up with publication. Some efforts have been made to assist clinicians to search or access the grey literature including aspects of the Cochrane Collaboration (see Section 1.7.3) and the following online instruments: the Australasian Digital Theses (ADT) Program and the Conference Papers Index.

1.7.7.1 The Australasian Digital Theses Program

The Australasian Digital Theses (ADT) Program began in 1998 and has been open to all Australian universities since 2000. It consists of a national collaborative of digitised theses produced at Australian universities (PhD and Masters by Research theses only). The program can be accessed free of charge via any internet-connected computer (see www.adt.caul.edu.au).

1.7.7.2 The Conference Papers Index

This database provides over 2.5 million citations to oral papers and poster sessions presented at major scientific conferences internationally from 1982 to the present. Major areas of subject coverage include healthcare, as well as biochemistry, chemistry, biology, biotechnology and many others. The Index is updated bimonthly and is available through subscribing health or academic institutions (see www.csa.com/factsheets/cpi-set-c.php).

1.8 Major structures promoting evidence-based practice

1.8.1 The National Institute of Clinical Studies

Reliable data on the gaps between clinical evidence (what research shows that clinicians should be doing in their clinical care) and clinical practice (what is actually done) is often difficult to find. Despite this, there have been sufficient published research studies to suggest that there is a gap problem in many healthcare systems. Dutch and American studies indicate that 30–40% of patients do not receive care based on the best research evidence, and that 20–25% of the care provided is either not needed or may be potentially harmful (Grol 2001, Schuster et al 1998).

The National Institute of Clinical Studies (NICS) is Australia’s national agency for improving healthcare by helping to close the gaps between best available evidence and current clinical practice. It was established as an Australian Government-owned company, run by a board of directors directly appointed by the Minister for Health, and commenced operations in 2001. On 1 April 2007, the NICS merged with the NHMRC in order to provide the NHMRC with the capacity to drive implementation of the clinical practice guidelines it develops and endorses (NHMRC 2008). The NICS and the NHMRC are working jointly on several projects, including a revision of the national infection control guidelines. In addition, a guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines is underway.

1.8.1.1 Why the need for the NICS?

In an editorial in the Medical Journal of Australia (Silagy 2001), the inaugural Chair of the NICS, the late Chris Silagy, observed that the language and concepts of evidence-based healthcare have become institutionalised in most spheres of healthcare, yet there are still significant gaps between evidence and practice.

1.8.1.2 What is important?

In 2002, the NICS established a nursing reference group of clinicians and academics to offer high-level advice on important practice gaps, and as a result of their recommendations, the NICS began work to scope opportunities to close the gaps in pain management and pressure-area management. This led to the NICS embarking on a major project to improve pain management in hospitalised patients with cancer, while the latter recommendation led the NICS to scope pressure-area care in Australia (see www.nhmrc.gov.au/nics).

Identification of EBP gaps is an evolutionary process and, in 2003, the NICS published the first in a projected series of reports highlighting important gaps identified by doctors, nurses, allied health clinicians and policy makers in Australia (NICS 2003). In 2005, a review of this report was undertaken (NICS 2005a) to provide a fresh look at what progress had been made in closing the gaps identified in the original report. Additionally, in 2005, a second volume in the series of evidence–practice gap reports was published, highlighting several areas where gaps between evidence and practice remain in day-to-day practice (NICS 2005b). See Appendix 1.1 for further details of clinical topics covered in these reports.

As our understanding of what actually happens in clinical practice improves and we look more deeply through better integration of routine data-collection systems at the surgery and bedside, it is anticipated that many more clinically significant gaps will be identified in the coming years.

1.8.1.3 What do we know about what works?

The NICS also aims to use expertise from areas such as behavioural psychology and marketing to better identify ways of systematically changing clinician behaviour in Australia. In 2003, the NICS convened a national workshop of clinicians and policy makers with an expertise in change management to identify better ways to manage change in Australian healthcare; the results of the workshop were published in 2004 (NICS 2004).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree