Evaluation in Healthcare Education

Priscilla Sandford Worral

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

Evaluation, Evidence-Based Practice, and Practice-Based Evidence

Evaluation Versus Assessment

Determining the Focus of Evaluation

Evaluation Models

Process (Formative) Evaluation

Content Evaluation

Outcome (Summative) Evaluation

Impact Evaluation

Total Program Evaluation

Designing the Evaluation

Design Structure

Evaluation Methods

Evaluation Instruments

Barriers to Evaluation

Conducting the Evaluation

Analyzing and Interpreting Data Collected

Reporting Evaluation Results

Be Audience Focused

Stick to the Evaluation Purpose

Use Data as Intended

State of the Evidence

KEY TERMS

evidence-based practice

external evidence

internal evidence

practice-based evidence

assessment

evaluation

process (formative) evaluation

content evaluation

outcome (summative) evaluation

impact evaluation

total program evaluation

evaluation research

reflective practice

OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

Define the term evaluation.

Discuss the relationships among evaluation, evidence-based practice, and practice-based evidence.

Compare and contrast evaluation and assessment.

Identify the purposes of evaluation.

Distinguish between five basic types of evaluation: process, content, outcome, impact, and program.

Discuss characteristics of various models of evaluation.

Describe similarities and differences between evaluation and research.

Assess barriers to evaluation.

Examine methods for conducting an evaluation.

Select appropriate instruments for various types of evaluative data.

Identify guidelines for reporting results of evaluation.

Describe the strength of the current evidence base for evaluation of patient and nursing staff education.

Evaluation is the process that can provide evidence that what we do as nurses and as nurse educators makes a value-added difference in the care we provide. Evaluation is defined as a systematic process by which the worth or value of something—in this case, teaching and learning—is judged.

Early consideration of evaluation has never been more critical than in today’s healthcare environment, which demands that “best” practice be based on evidence. Crucial decisions regarding learners rest on the outcomes of learning. Can the patient go home? Can the nurse provide competent care? If education is to be justified as a value-added activity, the process of education must be measurably efficient and must be measurably linked to education outcomes. The outcomes of education, both for the learner and for the organization, must be measurably effective.

Evaluation is a process within processes—a critical component of the nursing practice decision-making process and the education process. Evaluation is the final component of each of these processes. Because these processes are cyclical, evaluation serves as the critical bridge at the end of one cycle that provides evidence to guide direction of the next cycle.

The sections of this chapter follow the steps in conducting an evaluation. These steps include (1) determining the focus of the evaluation, including use of evaluation models; (2) designing the evaluation; (3) conducting the evaluation; (4) determining methods of analysis and interpretation of data collected; (5) reporting results of data collected; and (6) using evaluation results. Each of these aspects of the evaluation process is important, but all of them are meaningless if the results of evaluation are not used to guide future action in planning and carrying out educational interventions. In other words, the results of evaluation provide practice-based evidence to support continuing an educational intervention as is or revising that intervention to enhance learning.

EVALUATION, EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE, AND PRACTICE-BASED EVIDENCE

Evidence-based practice (EBP) can be defined as “the conscientious use of current best evidence in making decisions about patient care” (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011, p. 4). More broadly, EBP may be described as “a lifelong problem-solving approach to clinical practice that integrates … the most relevant and best research, … one’s own clinical expertise … and patient preferences and values” (p. 4). In their definition of evidence-based medicine, Straus, Richardson, Glasziou, and Haynes (2005), include these same three primary components, but also add “patient circumstances” (p. 1) to account for both the patient’s clinical state and the clinical setting.

Traditional EBP models describe evidence generated from systematic reviews of clinically relevant randomized controlled trials as the strongest evidence upon which to base practice decisions, especially decisions about treatment. More recent literature also describes evidence generated from meta-syntheses of rigorously conducted qualitative studies as providing the strongest evidence for informing nurses’ care of patients through a more thorough understanding of the patients’ experience and the context within which care is provided (Flemming, 2007; Goethals, Dierckx de Casterlé, & Gastmans, 2011; Taylor, Shaw, Dale & French, 2011). Evidence from research is also called external evidence, reflecting the fact that it is intended to be generalizable or transferrable beyond the particular study setting or sample.

As is discussed later in this chapter, results of evaluation are not considered external evidence. Evaluations are not intended to be generalizable, but rather are conducted to determine the effectiveness of a specific intervention in a specific setting with an identified individual or group. Although not considered external evidence, results of a systematically conducted evaluation are still important from an EBP perspective. When evidence generated from research is not available, the conscientious use of internal evidence is appropriate. Results of a systematically conducted evaluation are one example of internal evidence (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011).

Nurses’ understanding and use of EBP have evolved and expanded over the past two decades. One aspect of that evolution in recent years has been the adoption of the term practice-based evidence (Brownson & Jones, 2009; Girard, 2008; Green, 2008; Horn, Gassaway, Pentz, & James, 2010). Is discussion of practice-based evidence simply another way of addressing clinical expertise and patient circumstances, which are already components of EBP, and therefore redundant? Perhaps. A more useful perspective, however, might be to view practice-based evidence as a systematically constructed two-way bridge between external evidence and the practice setting. Defined as “the systematic collection of data about client progress generated during treatment to enhance the quality and outcomes of care” (Girard, 2008, p. 15), practice-based evidence comprises internal evidence that can be used both to identify whether a problem exists and to determine whether an intervention effectively resolved a problem. Put another way, practice-based evidence can be equally useful for assessment and for evaluation.

The results of evaluations, the outcomes of expert-delivered patient-centered care, and the results of quality improvement projects all represent internal evidence that is gathered by nurses and other healthcare professionals on an ongoing basis as an integral and important component of professional practice. Intentional recognition of these findings about current practice as a source of evidence to guide future practice requires that we think critically before acting and engage in

ongoing critical appraisal during and after each nurse-patient interaction.

ongoing critical appraisal during and after each nurse-patient interaction.

EVALUATION VERSUS ASSESSMENT

Although assessment and evaluation are highly interrelated and the terms are often used interchangeably, they are not synonymous. The process of assessment focuses on gathering, summarizing, interpreting, and using data to decide a direction for action. In contrast, the process of evaluation involves gathering, summarizing, interpreting, and using data to determine the extent to which an action was successful.

The primary differences between these two terms reflect the processes’ timing and purpose. For example, an education program begins with an assessment of learners’ needs. From the perspective of systems theory, assessment data might be called the “input.” While the program is being conducted, periodic evaluation lets the educator know whether the program and learners’ progress are proceeding as planned. After program completion, evaluation identifies whether and to what extent identified needs were met. Again, from a systems theory perspective, these evaluative data might be called “intermediate output” and “output,” respectively.

An important note of caution: Although an evaluation is conducted at the end of a program, that is not the time to plan it. Evaluation as an afterthought is, at best, a poor idea and, at worst, a dangerous one. At this point in the educational program, data may be impossible to collect, be incomplete, or even be misleading. Ideally, assessment and evaluation planning should be concurrent activities. When feasible, the same data collection methods and instruments should be used. This approach is especially appropriate for outcome and impact evaluations, as is discussed later in this chapter. “If only …” is an all too frequently heard lament, which can be minimized by planning ahead.

DETERMINING THE FOCUS OF EVALUATION

In planning any evaluation, the first and most crucial step is to determine the focus of the evaluation. This focus then guides evaluation design, conduct, data analysis, and reporting of results. The importance of a clear, specific, and realistic evaluation focus cannot be overemphasized. Usefulness and accuracy of the results of an evaluation depend heavily on how well the evaluation is initially focused.

Evaluation focus includes five basic components: (1) audience, (2) purpose, (3) questions, (4) scope, and (5) resources (Ruzicki, 1987). To identify these components, ask the following questions:

1. For which audience is the evaluation being conducted?

2. For which purpose is the evaluation being conducted?

3. Which questions will be asked in the evaluation?

4. What is the scope of the evaluation?

5. Which resources are available to conduct the evaluation?

The audience comprises the persons or groups for whom the evaluation is being conducted (Dillon, Barga, & Goodin, 2012; Ruzicki, 1987). These individuals or groups include the primary audience, or the individual or group who requested the evaluation, and the general audience, or all those who will use evaluation results or who might benefit from the evaluation. Thus the audience for an evaluation might include patients, peers, the manager of a unit, a supervisor, the nursing director, the staff development director, the chief executive officer of the institution, or a group of community leaders.

When an evaluator reports results of the evaluation, he or she provides feedback to all members of the audience. In focusing the evaluation,

however, the evaluator must first consider the primary audience. Giving priority to the individual or group that requested the evaluation makes it easier to focus the evaluation, especially if the results of an evaluation will be used by several groups representing diverse interests.

however, the evaluator must first consider the primary audience. Giving priority to the individual or group that requested the evaluation makes it easier to focus the evaluation, especially if the results of an evaluation will be used by several groups representing diverse interests.

The purpose of the evaluation is the answer to the question, “Why is the evaluation being conducted?” For example, the purpose might be to decide whether to continue a particular education program or to determine the effectiveness of the teaching process. If a particular individual or group has a primary interest in results of the evaluation, input from that group can clarify the purpose.

An important note of caution: Why an evaluator is conducting an evaluation is not synonymous with who or what the evaluator is evaluating. For example, nursing literature on patient education commonly distinguishes among three types of evaluations: (1) learner, (2) teacher, and (3) educational activity. This distinction answers the question of who or what will be evaluated and is extremely useful for evaluation design and conduct. The question of why learner evaluation might be undertaken, for example, is answered by the reason or purpose for evaluating learner performance. If the purpose for evaluating learner performance is to determine whether the learner gained sufficient skill to perform a self-care activity (e.g., foot care), the educator might design a content evaluation that includes one or more return demonstrations by an individual learner prior to hospital discharge. If the purpose for evaluating learner performance is to determine whether the learner is able to conduct the same self-care activity at home on a regular basis, the educator might design an outcome evaluation that includes both observing the learner perform the activity in his or her home environment and measuring other clinical parameters (e.g., skin integrity) that would improve and be maintained with regular and ongoing self-care. Content and outcome evaluations are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

An excellent rule of thumb in stating the purpose of an evaluation is to keep it singular. In other words, the evaluator should state, “The purpose is …,” not “The purposes are …”. Keeping the purpose focused on the audience and singular helps avoid the all too frequently encountered tendency to attempt too much in one evaluation. An exception to this rule is when undertaking a total program evaluation. As discussed later in this chapter, program evaluations are naturally broad in scope, focusing simultaneously on learners, teachers, and educational offerings.

Questions to be asked in the evaluation are directly related to the purpose for conducting the evaluation, are specific, and are measurable. Examples of such questions include “To what extent are patients satisfied with the cardiac discharge teaching program?” and “How frequently do staff nurses use the diabetes teaching reference materials?” Asking the right questions is crucial if the evaluation is to fulfill the intended purpose. As discussed later in this chapter, delineation of evaluation questions is both the first step in selection of evaluation design and the basis for eventual data analysis.

The scope of an evaluation can be considered an answer to the question, “How much will be evaluated?” “How much” includes “How many aspects of education will be evaluated?”, “How many individuals or representative groups will be evaluated?”, and “What time period is to be evaluated?” For example, will the evaluation focus on one class or on an entire program? Will it focus on the learning experience for one patient or for all patients being taught a particular skill? Evaluation could be limited to the teaching process during a particular patient education class, or it could be expanded to encompass both the teaching process and related patient outcomes of learning.

The scope of an evaluation is determined in part by the purpose for conducting the evaluation and in part by available resources. For example, an evaluation addressing learner satisfaction with educators for all programs conducted by a staff development department in a given year is necessarily broad and long term in scope; such a vast undertaking requires expertise in data collection and analysis. By comparison, an evaluation to determine whether a patient understands each step in a learning session on how to self-administer insulin injections is narrow in scope, is focused on a particular point in time, and requires expertise in clinical practice and observation.

Resources needed to conduct an evaluation include time, expertise, personnel, materials, equipment, and facilities. A realistic appraisal of which resources are accessible and available relative to which resources are required is crucial in focusing any evaluation. Someone conducting an evaluation should remember to include the time and expertise required to collate, analyze, and interpret data and to prepare the report of evaluation results.

EVALUATION MODELS

Evaluation can be classified into different types, or categories, based on one or more of the five components just described. The most common types of evaluation identified include some combination of process, or formative evaluation, and outcome, or summative evaluation. Other types of evaluation include content, outcome, impact, and total program evaluations. A number of evaluation models defining these evaluation types and how they relate to one another have been developed (Abruzzese, 1992; Frye & Hemmer, 2012; Milne, 2007; Noar, 2012; Ogrinc & Batalden, 2009; Rankin & Stallings, 2005; Rouse, 2011; Suhayda & Miller, 2006). Because not all models define types of evaluation in the same manner, the nurse educator should choose the model that is most appropriate for the given purpose and most realistic given the available resources.

Abruzzese (1992) constructed the Roberta Straessle Abruzzese (RSA) evaluation model for conceptualizing, or classifying, educational evaluation into different categories or levels. Although developed in 1978 and derived from the perspective of staff development education, the RSA model remains useful for conceptualizing types of evaluation from both staff development and patient education perspectives. Two more recent examples of use of the RSA model are given by Dilorio, Price, and Becker (2001) in their discussion of the evaluation of the Neuroscience Nurse Internship Program at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and by Underwood, Dahlen-Hartfield, and Mogle (2004) in their study of nurses’ perceived expertise following three continuing education programs. Sumner, Burke, Chang, McAdams, and Jones (2012) used the RSA model to support development of a study to evaluate process, content, and outcome evaluation of a basic arrhythmia course taught to registered nurses.

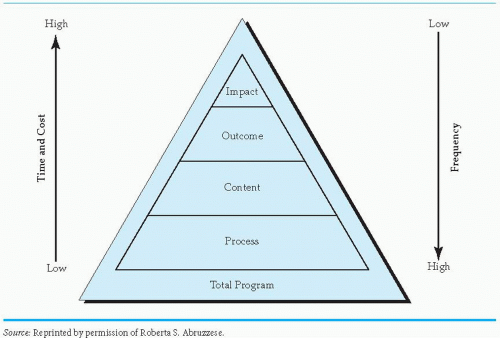

The RSA model pictorially places five basic types of evaluation in relation to one another based on purpose and related questions, scope, and resource components of evaluation focus (Figure 14-1). The five types of evaluation include process, content, outcome, impact, and total program. Abruzzese describes the first four types as levels of evaluation leading from the simple (process evaluation) to the complex (impact evaluation). Total program evaluation encompasses and summarizes all four levels.

Process (Formative) Evaluation

The purpose of process or formative evaluation is to make adjustments in an educational activity as soon as they are needed, whether those adjustments involve personnel, materials, facilities,

learning objectives, or even the educator’s own attitude. Adjustments may need to be made after one class or session and before the next is taught, or even in the middle of a single learning experience. Consider, for example, evaluating the process of teaching an adolescent with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and her family how to administer insulin. The nurse might facilitate learning by first injecting himself or herself with normal saline so that the learners can see someone maintain a calm expression during an injection. If the nurse educator had planned to have the parent give the first injection but the child seems less fearful, the nurse might consider revising the teaching plan to let the child first perform self-injection.

learning objectives, or even the educator’s own attitude. Adjustments may need to be made after one class or session and before the next is taught, or even in the middle of a single learning experience. Consider, for example, evaluating the process of teaching an adolescent with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes and her family how to administer insulin. The nurse might facilitate learning by first injecting himself or herself with normal saline so that the learners can see someone maintain a calm expression during an injection. If the nurse educator had planned to have the parent give the first injection but the child seems less fearful, the nurse might consider revising the teaching plan to let the child first perform self-injection.

Process evaluation is integral to the education process itself. It constitutes an educational activity because evaluation is an ongoing component of assessment, planning, and implementation. As part of the education process, this ongoing evaluation helps the nurse anticipate and prevent problems before they occur or identify problems as they arise. Milne’s (2007) structure-content-outcomes-procedures-processes-efficiencies (SCOPPE) framework and Noar’s (2012) audience-channel-message-evaluation (ACME) framework both focus heavily on detailed examination of the selection of teacher and learner as well as on examination of educational materials and teaching methods in defining aspects of process evaluation. Noar (2012) speaks to the

importance of a consistent theoretical framework as essential for unifying all aspects of educational design, conduct, and evaluation.

importance of a consistent theoretical framework as essential for unifying all aspects of educational design, conduct, and evaluation.

Consistent with the purpose of process evaluation, the primary question here is, “How can teaching be improved to facilitate learning?” The nurse’s teaching effectiveness, the teaching process, and the learner’s responses are monitored on an ongoing basis. Abruzzese (1992) describes process evaluation as a “happiness index.” While teaching and learning are ongoing, learners are asked their opinions about the educator(s), learning objectives, content, teaching and learning methods, physical facilities, and administration of the learning experience. For the nurse educator, specific questions could include the following:

Am I giving the patient time to ask questions?

Is the information I am giving orally consistent with information included in instructional materials being provided?

Does the patient look bored? Is the room too warm?

Should I include more opportunities for return demonstration?

The scope of process evaluation generally is limited in breadth and time period to a specific learning experience, such as a class or workshop, yet is sufficiently detailed to include as many aspects of the specific learning experience as possible while they occur. Learner behavior, teacher behavior, learner-teacher interaction, learner response to teaching methods and materials, and characteristics of the environment are all aspects of the learning experience within the scope of process evaluation. Whether they engage in the educational program online or on site, all learners and all teachers participating in a learning experience should be included in process evaluation. If resources are limited and participants include a number of different groups, a representative sample of individuals from each group—rather than everyone from each group—may be included in the evaluation.

Resources usually are less costly and more readily available for process evaluation than for other types of evaluation, such as impact or total program evaluation. Although process evaluation occurs more frequently—during and throughout every learning experience—than any other type, it occurs concurrently with teaching. The need for additional time, facilities, and dollars to conduct process evaluation is consequently decreased.

From the perspective of EBP, process evaluation is important in the use and patient-centered modification of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), sometimes referred to as clinical pathways or critical pathways, although not all are created using the same level of rigor. A well-constructed CPG includes not only the specific intervention—teaching a patient how to take his discharge medication, for example—but also the evidence-based process that should be used to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of that intervention.

Formal development of a CPG requires a high level of rigor and is intended for guiding care given to all patients who have similar characteristics and learning needs. As discussed later in this chapter, CPG development is conducted as evaluation research. Evaluation of the process of using a CPG, however, focuses on the fit of a CPG for a specific learner or learners. To the extent that a patient is the same as those patients who were studied in development of the CPG, the patient’s nurse will follow the guideline as written. To the extent that the patient has unique behaviors or responses to teaching, the nurse will use informal process evaluation to vary from the guideline to ensure that the patient is able to learn. CPGs are also useful for orientation of new healthcare employees, for quality improvement, and for evaluating clinical learning in student-precepted

situations. These pathways are used by members of the healthcare team as cost-effective and time-efficient measures to note learner progress and the achievement of goal-based outcomes. Implementing this education-focused evaluation method allows educators to choose learning experiences specific to the attainment of clinical outcomes (Bradshaw, 2007).

situations. These pathways are used by members of the healthcare team as cost-effective and time-efficient measures to note learner progress and the achievement of goal-based outcomes. Implementing this education-focused evaluation method allows educators to choose learning experiences specific to the attainment of clinical outcomes (Bradshaw, 2007).

EBP is not a “cookbook” approach to providing health care. Similarly, CPGs are not intended to be followed without regard for the individual learner. This does not mean that variance from a CPG occurs in a haphazard manner based on what may be convenient at the moment. Instead, as attention to practice-based evidence evolves, the importance of the conscientious use of internal evidence gathered from process evaluation is becoming an increasingly critical component of every teaching-learning experience.

For instance, Chan, Richardson, and Richardson (2012) describe a process evaluation conducted to examine which factors might support successful delivery of an intervention to improve symptom management for patients receiving palliative radiotherapy for their lung cancer. Although two nurses were using the same procedure to provide the intervention, patients were more satisfied with the nurse who had prior experience in oncology. Patients also were less likely to practice their muscle relaxation protocol if they had not yet experienced the level of pain that the muscle relaxation was intended to alleviate. Based on these findings, Chan and colleagues modified the intervention protocol to have patient education be provided by nurses with prior oncology experience and to allow patients flexibility in the frequency with which they practiced muscle relaxation techniques.

Jurasek, Ray, and Quigley (2010) describe use of a questionnaire to ask adolescents with epilepsy and their caregivers about the benefit of a transition clinic developed to ease the adolescents’ transition from pediatric to adult care. Results of the questionnaire are used to prioritize information provided to adolescents according to what they identify as their greatest concerns.

The importance of practice-based evidence to process evaluation encompasses staff education as well as patient education. Rani and Byrne (2012) conducted a multimethod evaluation of a training course geared toward teaching providers how to care for patients presenting with dual diagnosis of mental illness. A process evaluation conducted with an initial group of participants included daily collection of quantitative data using Likert scales to determine the extent to which participants found teaching methods and content covered that day to be helpful for their learning.

Milne’s SCOPPE framework and Noar’s ACME framework focus heavily on initial planning of the educational activity as an essential component of process evaluation that includes design of the education activity and examination.

Content Evaluation

The purpose of content evaluation is to determine whether learners have acquired the knowledge or skills taught during the learning experience. Abruzzese (1992) described content evaluation as taking place immediately after the learning experience to answer the guiding question, “To what degree did the learners learn what was imparted?” or “To what degree did learners achieve speci fied objectives?” Asking a patient to give a return demonstration and asking participants to complete a cognitive test at the completion of a 1-day seminar are common examples of content evaluation.

Content evaluation is depicted in the RSA model as the level in between process and outcome evaluation. In other words, content evaluation can be considered as focusing on how the

teaching-learning process affected immediate, short-term outcomes. To answer the question “Were specified objectives met as a result of teaching?” requires that the evaluation be designed differently from an evaluation to answer the question “Did learners achieve specified objectives?” Evaluation designs are discussed in some detail later in this chapter. An important point to be made here, however, is that evaluation questions must be carefully considered and clearly stated because they dictate the basic framework for design and conduct.

teaching-learning process affected immediate, short-term outcomes. To answer the question “Were specified objectives met as a result of teaching?” requires that the evaluation be designed differently from an evaluation to answer the question “Did learners achieve specified objectives?” Evaluation designs are discussed in some detail later in this chapter. An important point to be made here, however, is that evaluation questions must be carefully considered and clearly stated because they dictate the basic framework for design and conduct.

The scope of content evaluation is limited to a specific learning experience and to specifically stated objectives for that experience. Content evaluation occurs at a circumscribed point in time, immediately after completion of teaching, but encompasses all teaching-learning activities included in that specific learning experience. Data are obtained from all learners targeted in a specific class or group. For example, if both parents and the juvenile patient with diabetes are taught insulin administration, all three are asked to complete a return demonstration. Similarly, all nurses attending a workshop are asked to complete the cognitive posttest at the end of the workshop.

Resources used to teach content can also be used to carry out an evaluation of how well that content was learned. For example, the same equipment included in teaching a patient how to change a dressing can be used by the patient to perform a return demonstration. In the same manner, a pretest used at the beginning of a continuing education seminar can be readministered as a posttest at seminar completion to measure change as a result of the program.

From the perspective of practice-based evidence, content evaluation, like process evaluation, focuses on collecting internal evidence to determine whether objectives for a specific group of learners were met. Internal evidence must include both baseline data and immediate outcome data so that any change in learning can be demonstrated.

Walker (2012) describes development and implementation of Skin Protection for Kids, a primary prevention education project aimed at school-aged children and their parents and teachers to decrease unnecessary sun exposure. Content evaluation included pretests conducted prior to provision of informational materials and posttests conducted 24 to 48 hours later. Teachers’ scores improved from an average of 56.25% on the pretest to an average of 87.5% on the posttest, indicating that teachers improved their short-term knowledge of sun safety.

Cibulka (2011) provides an example of content evaluation in her description of a continuing education program on research ethics in which nurses completed quizzes after each module to determine short-term knowledge retention. Cibulka’s use of quiz scores already developed and integrated into a well-known and widely used research ethics educational activity exemplifies an important rule of thumb: Use existing data if those data are relevant and already available. Asking any individual to spend his or her time to complete a quiz, survey, or any data collection activity should be viewed by the person collecting those data as a promise to use the data collected appropriately.

Outcome (Summative) Evaluation

The purpose of outcome or summative evaluation is to determine the effects or outcomes of teaching efforts. Its intent is to summarize what happened as a result of education. Guiding questions in outcome evaluation include the following:

Was teaching appropriate?

Did the individual(s) learn?

Were behavioral objectives met?

Did the patient who learned a skill before discharge use that skill correctly once home?

Just as process evaluation occurs concurrently with the teaching-learning experience, so outcome evaluation occurs after teaching has been completed or after a program has been carried out. Outcome evaluation measures the changes that result from teaching and learning.

Abruzzese (1992) differentiates outcome evaluation from content evaluation by noting that outcome evaluation measures more long-term change that “persists after the learning experience” (p. 243). Changes can include institution of a new process, habitual use of a new technique or behavior, or integration of a new value or attitude. Which changes the nurse educator measures usually are dictated by the objectives established as a result of the initial needs assessment.

The scope of outcome evaluation depends in part on the changes being measured, which in turn depend on the objectives established for the educational activity. As mentioned earlier, outcome evaluation focuses on a longer time period than does content evaluation. Whereas evaluating the accuracy of a patient’s return demonstration of a skill prior to discharge may be appropriate for content evaluation, outcome evaluation should include measuring a patient’s competency with a skill in the home setting after discharge. Similarly, nurses’ responses on a workshop posttest may be sufficient for content evaluation, but if the workshop objective states that nurses will be able to incorporate their knowledge into practice on the unit, outcome evaluation should include measuring nurses’ knowledge or behavior at some time after they have returned to the unit. Abruzzese (1992) suggests that outcome data be collected 6 months after baseline data to determine whether a change has really taken place.

Resources required for outcome evaluation are more costly and sophisticated than those needed for process or content evaluation. Compared to the resources required for the first two types of evaluation in the RSA model, outcome evaluation requires greater expertise to develop measurement and data collection strategies, more time to conduct the evaluation, knowledge of baseline data establishment, and ability to collect reliable and valid comparative data after the learning experience. Postage to mail surveys and time and personnel to carry out observation of nurses on the clinical unit or to complete patient/family telephone interviews are specific examples of resources that may be necessary to conduct an outcome evaluation.

From an EBP perspective, outcome evaluation might arguably be considered as “where the rubber meets the road.” Once a need for change has been identified, the search for evidence on which to base subsequent changes commonly begins with a structured clinical question that will guide an efficient search of the literature. This question is also known as a PICO question, where the letters P, I, C, and O stand for population (patient, staff, or student), intervention, comparison, and outcome, respectively.

For example, nurses caring for an outpatient population of adults with heart failure might discover that many patients are not following their prescribed treatment regimen. Upon questioning these patients, the nurses learn that a majority of the patients do not recognize symptoms resulting from failure to take their medications on a consistent basis. To search the literature efficiently for ways in which they might better educate their patients, the nurses would pose the following PICO question: Does nurse-directed patient education on symptoms and related treatment for heart failure provided to adult outpatients with heart failure result in improved compliance with treatment regimens? In this example, the P is adult outpatients with heart failure, the I is the nurse-directed patient education on symptoms and related treatment for heart failure, the C is inferred as education currently being provided (or lack of education, if that is the case), and the O is improved compliance with treatment regimens.

The Skin Protection for Kids program (Walker, 2012) included outcome evaluation as well as the content evaluation described earlier in this chapter. Whereas content evaluation of teachers’ knowledge was conducted 24 to 48 hours after the educational activity, outcome evaluation to measure whether sun-safety practices were implemented by children took place several months later.

Ideally, several well-conducted studies providing external evidence directly relevant to a PICO question should be reviewed prior to making a practice change, especially if that change is resource intensive or, if unsuccessful, might increase patient risk. Implementation of the Skin Protection for Kids program (Walker, 2012) is an excellent example of a practice change based on review and appraisal of external evidence. In this program’s development, the researchers considered 39 studies plus systematic reviews, peer-reviewed guidelines, and literature reviews that focused on sun-safety measures for children.

Another example of an outcome evaluation was a study conducted by Sumner et al. (2012) to determine whether nurses completing a basic arrhythmia course retained knowledge four weeks after course completion and accurately identified cardiac rhythms three months later. An initial content evaluation demonstrated that the 62 nurses who completed the course improved their short-term knowledge from pretest to posttest to a statistically significantly degree (p < 0.01). Nurses’ scores on a simulated arrhythmia experience conducted three months later demonstrated no significant change from posttest scores obtained immediately after course completion. Ideally, an outcome evaluation to answer the question “Were nurses who completed a basic arrhythmia course able to use their skills in the practice setting?” should be conducted by directly observing those nurses during patient care. Given the logistical challenges of unobtrusively directly observing nurses when patients are actually experiencing the arrhythmias included in the course, however, use of simulation may be considered a feasible alternative—as long as the educator remembers that simulation is merely a proxy for reality.

Impact Evaluation

The purpose of impact evaluation is to determine the relative effects of education on the institution or the community. Put another way, the purpose of impact evaluation is to obtain information that will help decide whether continuing an educational activity is worth its cost. Examples of questions appropriate for impact evaluation include “What is the effect of an orientation program on subsequent nursing staff turnover?” and “What is the effect of a cardiac discharge teaching program on long-term frequency of rehospitalization among patients who have completed the program?”

The scope of impact evaluation is broader, more complex, and usually more long term than that of process, content, or outcome evaluation. For example, whereas outcome evaluation focuses on whether specific teaching results in achievement of specified outcomes, impact evaluation goes beyond that point to measure the effect or worth of those outcomes. In other words, outcome evaluation focuses on a learning objective, whereas impact evaluation focuses on a goal for learning. Consider, for instance, a class on the use of body mechanics. The objective is that staff members will demonstrate proper use of body mechanics in providing patient care. The goal is to decrease back injuries among the hospital’s directcare providers. This distinction between outcome and impact evaluation may seem subtle, but it is important to the appropriate design and conduct of an impact evaluation.

Good science is rarely inexpensive and never quick; good impact evaluation shares the same

characteristics. The resources needed to design and conduct an impact evaluation generally include reliable and valid instruments, trained data collectors, personnel with research and statistical expertise, equipment and materials necessary for data collection and analysis, and access to populations who may be culturally or geographically diverse. Kobb, Lane, and Stallings (2008) describe an impact evaluation of e-learning as a method for building telehealth skills that spanned the entire Veterans Health Administration system and was initiated three years after e-learning was implemented. These characteristics exemplify the scope and time frame commonly found with this type of evaluation. An example illustrating how an impact evaluation can be global in nature is provided by Padian et al. (2011) in their discussion of challenges facing those persons who conduct large-scale evaluations of combination HIV prevention programs.

characteristics. The resources needed to design and conduct an impact evaluation generally include reliable and valid instruments, trained data collectors, personnel with research and statistical expertise, equipment and materials necessary for data collection and analysis, and access to populations who may be culturally or geographically diverse. Kobb, Lane, and Stallings (2008) describe an impact evaluation of e-learning as a method for building telehealth skills that spanned the entire Veterans Health Administration system and was initiated three years after e-learning was implemented. These characteristics exemplify the scope and time frame commonly found with this type of evaluation. An example illustrating how an impact evaluation can be global in nature is provided by Padian et al. (2011) in their discussion of challenges facing those persons who conduct large-scale evaluations of combination HIV prevention programs.

Because impact evaluation is so expensive and resource intensive, this type of evaluation is usually beyond the scope of the individual nurse educator. Conducting an impact evaluation may seem to be a monumental task, but this reality should not dissuade the determined educator from the effort. Rather, one should plan ahead, proceed carefully, and obtain the support and assistance of stakeholders and colleagues. Keeping in mind the purpose for conducting an impact evaluation should be helpful in maintaining the level of commitment needed throughout the process. The current managed care environment requires justification for every health dollar spent. The value of patient and staff education may be intuitively evident, but the positive impact of education must be demonstrated if it is to be funded.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree